Brick and Click Libraries an Academic Library Symposium Northwest Missouri State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Google Apps Premier Edition: Easy, Collaborative Workgroup Communication with Gmail and Google Calendar

Google Apps Premier Edition: easy, collaborative workgroup communication with Gmail and Google Calendar Messaging overview Google Apps Premier Edition messaging tools include email, calendar and instant messaging solutions that help employees communicate and stay connected, wherever and whenever they work. These web-based services can be securely accessed from any browser, work on mobile devices like BlackBerry and iPhone, and integrate with other popular email systems like Microsoft Outlook, Apple Mail, and more. What’s more, Google Apps’ SAML-based Single Sign-On (SSO) capability integrates seamlessly with existing enterprise security and authentication services. Google Apps deliver productivity and reduce IT workload with a hosted, 99.9% uptime solution that gets teams working together fast. Gmail Get control of spam Advanced filters keep spam from employees’ inboxes so they can focus on messages that matter, and IT admins can focus on other initiatives. Keep all your email 25 GB of storage per user means that inbox quotas and deletion schedules are a thing of the past. Integrated instant messaging Connect with contacts instantly without launching a separate application or leaving your inbox. No software required. Built-in voice and video chat Voice and video conversations, integrated into Gmail, make it easy to connect face-to-face with co-workers around the world. Find messages instantly Powerful Google search technology is built into Gmail, turning your inbox into your own private and secure Google search engine for email. Protect and secure sensitive information Additional spam filtering from Postini provides employees with an additional layer of protection and policy-enforced encryption between domains using standard TLS protocols. -

In Afghanistan Afsar Sadiq Shinwari* School of Journalism and Communication, Hebei University, Baoding, Hebei, China

un omm ica C tio Shinwari, J Mass Communicat Journalism 2019, 9:1 s n s a & M J o f u o Journal of r l n a a n l r i s u m o J ISSN: 2165-7912 Mass Communication & Journalism Review Article OpenOpen Access Access Media after Interim Administration (December/2001) in Afghanistan Afsar Sadiq Shinwari* School of Journalism and Communication, Hebei University, Baoding, Hebei, China Abstract The unbelievable growth of media since 2001 is one of the greatest achievements of Afghan government. Now there are almost 800 publications, 100TV and 302 FM radio stations, 6 telecommunication companies, tens of news agencies, more than 44 licensed ISPs internet provider companies and several number of production groups are busy to broadcast information, drama serial, films according to the afghan Culture, and also connected the people with each other on national and international level. Afghanistan is a nation of 30 million people, and a majority live in its 37,000 villages. But low literacy rate (38.2%) is the main obstacle in Afghanistan, most of the people who lived in rural area are not educated and they are only have focus on radio and TV broadcasting. So, the main purpose of this study is the rapid growth of media in Afghanistan after the Taliban regime, but most of those have uncertain future. Keywords: Traditional media; New media; Social media; Media law programs and also a huge number of publications, mobile Networks, press clubs, newspaper, magazines, news agencies and internet Introduction were appeared at the field of information and technology. -

Wrth2016intradiosuppl2 A16

This file is a supplement to the 2016 edition of World Radio TV Handbook, and summarises the changes to the schedules printed in the book resulting from the implementation of the 2016 “A” season schedules. Contact details and other information about the stations shown in this file can be found in the International Radio section of WRTH 2016. If you haven’t yet got your copy, the book can be ordered from Amazon, your nearest bookstore or directly from our website at www.wrth.com/_shop WRTH INTERNATIONAL RADIO SCHEDULES - MAY 2016 Notes for the International Radio section Country abbreviation codes are shown after the country name. The three-letter codes after each frequency are transmitter site codes. These, and the Area/Country codes in the Area column, can be decoded by referring to the tables in the at the end of the file. Where a frequency has an asterisk ( *) etc. after it, see the ‘ KEY ’ section at the end of the sched - ule entry. The following symbols are used throughout this section: † = Irregular transmissions/broadcasts; ‡ = Inactive at editorial deadline; ± = variable frequency; + = DRM (Digital Radio Mondiale) transmission. ALASKA (ALS) ANGOLA (AGL) KNLS INTERNATIONAL (Rlg) ANGOLAN NATIONAL RADIO (Pub) kHz: 7355, 9655, 9920, 11765, 11870 kHz: 945 Summer Schedule 2016 Summer Schedule 2016 Chinese Days Area kHz English Days Area kHz 0800-1200 daily EAs 9655nls 2200-2300 daily SAf 945mul 1300-1400 daily EAs 9655nls, 9920nls French Days Area kHz 1400-1500 daily EAs 7355nls 2100-2200 daily SAf 945mul English Days Area kHz Lingala -

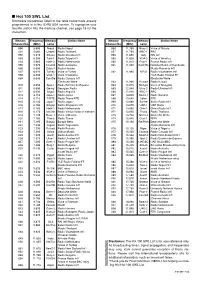

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Requirements for Using Hangouts Meet

Requirements for using Hangouts Meet • Hangouts Meet access requirements • Video meeting requirements Hangouts Meet access requirements • A G Suite administrator needs to turn on Meet for your organization. If you cannot open Meet, contact your admin for help. • To create a video meeting, you need to be signed in to a G Suite account. • To join a video meeting, you need the Meet mobile app or a supported web browser. You do not need a G Suite account. For details, see Supported web browsers. • Anyone inside or outside of your organization can join by selecting the link or entering the meeting ID. Uninvited guests outside of your organization must be approved by a meeting participant in your organization, including users who aren’t signed in to a G Suite account. Video meeting requirements Before you start a video meeting, be sure you're using equipment that supports Hangouts Meet. Open all | Close all Use a supported operating system Meet supports the current version and the 2 previous major releases of these operating systems: • Apple® macOS® • Microsoft® Windows® • Chrome OS • Ubuntu® and other Debian-based Linux® distributions Use a supported web browser Meet works with the current version of the browsers listed below: • Chrome Browser. Download the latest version • Mozilla® Firefox®. Download the latest version • Microsoft® Edge®. Download the latest version • Apple® Safari®. Meet has limited support in Microsoft Internet Explorer® 11, Microsoft Edge provides a better Meet experience. If you want to use Internet Explorer for Hangouts, you need to install a plugin for Meet. Download and install the latest version of the Google Video Support plugin. -

Dx Magazine 12/2003

12 - 2003 All times mentioned in this DX MAGAZINE are UTC - Alle Zeiten in diesem DX MAGAZINE sind UTC Staff of WORLDWIDE DX CLUB: PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EDITOR ..C WWDXC Headquarters, Michael Bethge, Postfach 12 14, D-61282 Bad Homburg, Germany B daytime +49-6102-2861, evening/weekend +49-6172-390918 F +49-6102-800999 E-Mail: [email protected] V Internet: http://www.wwdxc.de BROADCASTING NEWS EDITOR . C Dr. Jürgen Kubiak, Goltzstrasse 19, D-10781 Berlin, Germany E-Mail: [email protected] LOGBOOK EDITOR .............C Ashok Kumar Bose, Apt. #421, 3420 Morning Star Drive, Mississauga, ON, L4T 1X9, Canada V E-Mail: [email protected] QSL CORNER EDITOR ..........C Richard Lemke, 60 Butterfield Crescent, St. Albert, Alberta, T8N 2W7, Canada V E-Mail: [email protected] TOP NEWS EDITOR (Internet) ....C Wolfgang Büschel, Hoffeld, Sprollstrasse 87, D-70597 Stuttgart, Germany V E-Mail: [email protected] TREASURER & SECRETARY .....C Karin Bethge, Urseler Strasse 18, D-61348 Bad Homburg, Germany NEWCOMER SERVICE OF AGDX . C Hobby-Beratung, c/o AGDX, Postfach 12 14, D-61282 Bad Homburg, Germany (please enclose return postage) Each of the editors mentioned above is self-responsible for the contents of his composed column. Furthermore, we cannot be responsible for the contents of advertisements published in DX MAGAZINE. We have no fixed deadlines. Contributions may be sent either to WWDXC Headquarters or directly to our editors at any time. If you send your contributions to WWDXC Headquarters, please do not forget to write all contributions for the different sections on separate sheets of paper, so that we are able to distribute them to the competent section editors. -

Disciplining Sexual Deviance at the Library of Congress Melissa A

FOR SEXUAL PERVERSION See PARAPHILIAS: Disciplining Sexual Deviance at the Library of Congress Melissa A. Adler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Library and Information Studies) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 5/8/2012 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Christine Pawley, Professor, Library and Information Studies Greg Downey, Professor, Library and Information Studies Louise Robbins, Professor, Library and Information Studies A. Finn Enke, Associate Professor, History, Gender and Women’s Studies Helen Kinsella, Assistant Professor, Political Science i Table of Contents Acknowledgements...............................................................................................................iii List of Figures........................................................................................................................vii Crash Course on Cataloging Subjects......................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Setting the Terms: Methodology and Sources.......................................................5 Purpose of the Dissertation..........................................................................................6 Subject access: LC Subject Headings and LC Classification....................................13 Social theories............................................................................................................16 -

Paper #5: Google Mobile

Yale University Thurmantap Arnold Project Digital Platform Theories of Harm Paper Series: 5 Google’s Anticompetitive Practices in Mobile: Creating Monopolies to Sustain a Monopoly May 2020 David Bassali Adam Kinkley Katie Ning Jackson Skeen Table of Contents I. Introduction 3 II. The Vicious Circle: Google’s Creation and Maintenance of its Android Monopoly 5 A. The Relationship Between Android and Google Search 7 B. Contractual Restrictions to Android Usage 8 1. Anti-Fragmentation Agreements 8 2. Mobile Application Distribution Agreements 9 C. Google’s AFAs and MADAs Stifle Competition by Foreclosing Rivals 12 1. Tying Google Apps to GMS Android 14 2. Tying GMS Android and Google Apps to Google Search 18 3. Tying GMS Apps Together 20 III. Google Further Entrenches its Mobile Search Monopoly Through Exclusive Dealing22 A. Google’s Exclusive Dealing is Anticompetitive 25 IV. Google’s Acquisition of Waze Further Forecloses Competition 26 A. Google’s Acquisition of Waze is Anticompetitive 29 V. Google’s Anticompetitive Actions Harm Consumers 31 VI. Google’s Counterarguments are Inadequate 37 A. Google Android 37 B. Google’s Exclusive Contracts 39 C. Google’s Acquisition of Waze 40 VII. Legal Analysis 41 A. Google Android 41 1. Possession of Monopoly Power in a Relevant Market 42 2. Willful Acquisition or Maintenance of Monopoly Power 43 a) Tying 44 b) Bundling 46 B. Google’s Exclusive Dealing 46 1. Market Definition 47 2. Foreclosure of Competition 48 3. Duration and Terminability of the Agreement 49 4. Evidence of Anticompetitive Intent 50 5. Offsetting Procompetitive Justifications 51 C. Google’s Acquisition of Waze 52 1. -

Download The

TECTAS: Bridging the Gap Between Collaborative Tagging Systems and Structured Data by Seyyed Ali Moosavi B.Sc. in Computer Engineering, Sharif University of Technology, 2008 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Computer Science) The University Of British Columbia (Vancouver) October 2010 c Seyyed Ali Moosavi, 2010 Abstract Ontologies are core building block of the emerging semantic web, and taxonomies which contain class-subclass relationships between concepts are a key component of ontologies. A taxonomy that relates the tags in a collaborative tagging system, makes the collaborative tagging system’s underlying structure easier to understand. Automatic construction of taxonomies from various data sources such as text data and collaborative tagging systems has been an interesting topic in the field of data mining. This thesis introduces a new algorithm for building a taxonomy of keywords from tags in collaborative tagging systems. This algorithm is also capable of de- tecting has-a relationships between tags. Proposed method — the TECTAS algo- rithm — uses association rule mining to detect is-a relationships between tags and can be used in an automatic or semi-automatic framework. TECTAS algorithm is based on the hypothesis that users tend to assign both “child” and “parent” tags to a resource. Proposed method leverages association rule mining algorithms, bi-gram pruning using search engines, discovering relationships when pairs of tags have a common child, and lexico-syntactic patterns to detect meronyms. In addition to proposing the TECTAS algorithm, several experiments are re- ported using four real data sets — Del.icio.us, LibraryThing, CiteULike, and IMDb. -

Reading Indicators on the Social Networks Goodreads and Librarything and Their Impact on Amazon Nieves González-Fernández- Villavicencio (Sevilla)

Reading indicators on the social networks Goodreads and LibraryThing and their impact on Amazon Nieves González-Fernández- Villavicencio (Sevilla) Summary: The aim of this paper is to identify relations between the most reviews and ratings books in Goodreads and LibraryThing, two of the most impacting social net- works of reading, and the list of top-selling titles in Amazon, the giant of the distribu- tion. After a description of both networks and study of their web impact, we have con- ducted an analysis of correlations in order to see the level of dependency between sta- tistical data they offer and the list of top-selling in Amazon. Only some slight evidences have been found. However there appears to be a strong or moderate correlation between the rest of the data, according to that we propose a battery of indicators to measure the book impact on reading. Keywords: Goodreads, LibraryThing, reading social networks, virtual reading clubs, reading indicators, Amazon 1 Epitexts, social reading networks and promotion of reading1 It is acknowledged that social media in general has become a way of com- municating to share a whole series of habits, behaviours and tastes, including reading and sharing books. This is the context in which Lluch et al. (2015: 798) deploy the concept of epitext and Jenkins’s notion of inter- active audiences, which are fostered by the social web and refer to groups of readers whose attention is focused on books and reading-related issues. «What we have are virtual identities for which it is equally important to keep abreast of the latest publishing releases and to exchange knowledge and opinions about books that they read, authors whom they like, themes and so forth» (Lluch et al., 2015: 798). -

Social Cataloguing Sites: Features and Implications for Cataloguing Practice and the Public Library Catalogue

SOCIAL CATALOGUING SITES: FEATURES AND IMPLICATIONS FOR CATALOGUING PRACTICE AND THE PUBLIC LIBRARY CATALOGUE Louise F. Spiteri School of Information Management Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia. Canada Louise.HTU [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper examines and evaluates the social features and comprehensiveness of the catalogue records of 16 popular social cataloguing web sites to determine whether their social and cataloguing features could or should impact the design of library catalogue records. Selected monograph records were evaluated to determine the extent to which they contained the standard International Standard Bibliographic Description elements used in Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules-based cataloguing practice, with emphasis placed on the physical description of the records. The heuristics Communication, Identity, and Perception were used to evaluate the sites‘ social features. Although the bibliographic content of most of the catalogue records examined was poor when assessed by professional cataloguing practice, their social features can help make the library catalogue a lively community of interest where people can share their reading interests with one another. KEYWORDS: Cataloguing; Library catalogues; Social cataloguing; Social software; Tagging 40 INTRODUCTION The phenomenon of web-based social communities, such as Facebook and MySpace, and social bookmarking sites, such as Del.icio.us and Flickr, has increased greatly in popularity. Wikipedia, for example, lists 20 popular bookmarking sites, as of July 2008 (Wikipedia, 2008), and this number may likely continue to grow. More recently, we have seen the growth in popularity of social cataloguing communities, whose aims and objectives are to allow members to catalogue and share with each other items that they own, such as books, DVDs, audio CDs, and so forth, as well as to note items on their wish lists (i.e., what they would like to purchase or borrow, view, or read). -

Video Quality Measurement for 3G Handset

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2007 Video Quality Measurement for 3G Handset Zeeshan http://hdl.handle.net/10026.2/509 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Video Quality Measurement for 3G Handset by Zeeshan Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Master of Research in Communications Engineering and Signal Processing in School of Computing, Communication and Electronics University of Plymouth January 2007 Supervisors Professor Emmanuel C. Ifeachor Dr. Lingfen Sun Mr. Zhuoqun Li © Zeeshan 2007 University of Plymouth Library Item no. „ . ^ „ Declaration This is to certify that the candidate, Mr. Zeeshan, carried out the work submitted herewith Candidate's Signature: Mr. Zeeshan KJ(. 'X&_.XJ<t^ Date: 25/01/2007 Supervisor's Signature: Dr. Lingfen Sun /^i^-^^^^f^ » P^^^. 25/01/2007 Second Supervisor's Signature: Mr. Zhuoqun Li / Date: 25/01/2007 Copyright & Legal Notice This copy of the dissertation has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognize that its copyright rests with its author and that no part of this dissertation and information derived from it may be published without the author's prior written consent.