Herese Quinn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections on the Production of the Finno-Ugric Exhibitions at the Estonian National Museum

THE ETHICS OF ETHNOGRAPHIC ATTRACTION: REFLECTIONS ON THE PRODUCTION OF THE FINNO-UGRIC EXHIBITIONS AT THE ESTONIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM SVETLANA KARM Researcher Estonian National Museum Veski 32, 51014 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ART LEETE Professor of Ethnology University of Tartu Ülikooli 18, 50090 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT We intend to explore* the production of the Finno-Ugric exhibitions at the Esto- nian National Museum. Our particular aim is to reveal methodological changes of ethnographic reproduction and to contextualise the museum’s current efforts in ideologically positioning of the permanent exhibition. Through historical–herme- neutical analysis we plan to establish particular museological trends at the Esto- nian National Museum that have led curators to the current ideological position. The history of the Finno-Ugric displays at the Estonian National Museum and comparative analysis of international museological practices enable us to reveal and interpret different approaches to ethnographic reconstructions. When exhib- iting indigenous cultures, one needs to balance ethnographic charisma with the ethics of display. In order to employ the approach of ethical attraction, curators must comprehend indigenous cultural logic while building up ethnographic rep- resentations. KEYWORDS: Finno-Ugric • permanent exhibition • museum • ethnography • ethics INTRODUCTION At the current time the Estonian National Museum (ENM) is going through the process of preparing a new permanent exhibition space. The major display will be dedicated to Estonian cultural developments. A smaller, although still significant, task is to arrange the Finno-Ugric permanent exhibition. The ENM has been involved in research into the Finno-Ugric peoples as kindred ethnic groups to the Estonians since the museum was * This research was supported by the European Union through the European Regional Devel- opment Fund (Centre of Excellence in Cultural Theory, CECT), and by the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research (projects PUT590 and ETF9271). -

Alevist Vallamajani from Borough to Community House

Eesti Vabaõhumuuseumi Toimetised 2 Alevist vallamajani Artikleid maaehitistest ja -kultuurist From borough to community house Articles on rural architecture and culture Tallinn 2010 Raamatu väljaandmist on toetanud Eesti Kultuurkapital. Toimetanud/ Edited by: Heiki Pärdi, Elo Lutsepp, Maris Jõks Tõlge inglise keelde/ English translation: Tiina Mällo Kujundus ja makett/ Graphic design: Irina Tammis Trükitud/ Printed by: AS Aktaprint ISBN 978-9985-9819-3-1 ISSN-L 1736-8979 ISSN 1736-8979 Sisukord / Contents Eessõna 7 Foreword 9 Hanno Talving Hanno Talving Ülevaade Eesti vallamajadest 11 Survey of Estonian community houses 45 Heiki Pärdi Heiki Pärdi Maa ja linna vahepeal I 51 Between country and town I 80 Marju Kõivupuu Marju Kõivupuu Omad ja võõrad koduaias 83 Indigenous and alien in home garden 113 Elvi Nassar Elvi Nassar Setu küla kontrolljoone taga – Lõkova Lykova – Setu village behind the 115 control line 149 Elo Lutsepp Elo Lutsepp Asustuse kujunemine ja Evolution of settlement and persisting ehitustraditsioonide püsimine building traditions in Peipsiääre Peipsiääre vallas. Varnja küla 153 commune. Varnja village 179 Kadi Karine Kadi Karine Miljööväärtuslike Virumaa Milieu-valuable costal villages of rannakülade Eisma ja Andi väärtuste Virumaa – Eisma and Andi: definition määratlemine ja kaitse 183 of values and protection 194 Joosep Metslang Joosep Metslang Palkarhitektuuri taastamisest 2008. Methods for the preservation of log aasta uuringute põhjal 197 architecture based on the studies of 2008 222 7 Eessõna Eesti Vabaõhumuuseumi toimetiste teine köide sisaldab 2008. aasta teaduspäeva ettekannete põhjal kirjutatud üpris eriilmelisi kirjutisi. Omavahel ühendab neid ainult kaks põhiteemat: • maaehitised ja maakultuur. Hanno Talvingu artikkel annab rohkele arhiivimaterjalile ja välitööaine- sele toetuva esmase ülevaate meie valdade ja vallamajade kujunemisest alates 1860. -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2014 XX

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEAR BOOK ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XX (47) 2014 TALLINN 2015 ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES The Year Book was compiled by: Margus Lopp (editor-in-chief) Galina Varlamova Ülle Rebo, Ants Pihlak (translators) ISSN 1406-1503 © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA CONTENTS Foreword . 5 Chronicle . 7 Membership of the Academy . 13 General Assembly, Board, Divisions, Councils, Committees . 17 Academy Events . 42 Popularisation of Science . 48 Academy Medals, Awards . 53 Publications of the Academy . 57 International Scientific Relations . 58 National Awards to Members of the Academy . 63 Anniversaries . 65 Members of the Academy . 94 Estonian Academy Publishers . 107 Under and Tuglas Literature Centre of the Estonian Academy of Sciences . 111 Institute for Advanced Study at the Estonian Academy of Sciences . 120 Financial Activities . 122 Associated Institutions . 123 Associated Organisations . 153 In memoriam . 200 Appendix 1 Estonian Contact Points for International Science Organisations . 202 Appendix 2 Cooperation Agreements with Partner Organisations . 205 Directory . 206 3 FOREWORD The Estonian science and the Academy of Sciences have experienced hard times and bearable times. During about the quarter of the century that has elapsed after regaining independence, our scientific landscape has changed radically. The lion’s share of research work is integrated with providing university education. The targets for the following seven years were defined at the very start of the year, in the document adopted by Riigikogu (Parliament) on January 22, 2014 and entitled “Estonian research and development and innovation strategy 2014- 2020. Knowledge-based Estonia”. It starts with the acknowledgement familiar to all of us that the number and complexity of challenges faced by the society is ever increasing. -

The Ethnographic Films Made by the Estonian National Museum (1961–1989) Liivo Niglas, Eva Toulouze

Reconstructing the Past and the Present: the Ethnographic Films Made by the Estonian National Museum (1961–1989) Liivo Niglas, Eva Toulouze To cite this version: Liivo Niglas, Eva Toulouze. Reconstructing the Past and the Present: the Ethnographic Films Made by the Estonian National Museum (1961–1989): Reconstruire le passé et le présent: les films ethno- graphiques réalisés par le Musée national estonien (1961–1989). Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics, University of Tartu, Estonian National Museum and Estonian Literary Museum., 2010, 4 (2), pp.79-96. hal-01276198 HAL Id: hal-01276198 https://hal-inalco.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01276198 Submitted on 19 Feb 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. RECOnstruCtinG THE PAst AND THE Present: THE ETHNOGR APHIC Films MADE BY THE EstOniAN NAtiONAL Museum (1961–1989) LIIVO NIGLAS MA, Researcher Department of Ethnology Institute for Cultural Research and Fine Arts University of Tartu Ülikooli 18, 50090, Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] EVA TOULOUZE PhD Hab., Associate Professor Department of Central and Eastern Europe Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales (INALCO) 2, rue de Lille, 75343 Paris, France e-mail: [email protected] ABstrACT This article* analyses the films made by the Estonian National Museum in the 1970s and the 1980s both from the point of view of the filming activity and of the content of these films. -

1 Estonian University of Life Sciences Kreutzwaldi 1

ESTONIAN LANGUAGE AND CULTURE COURSE (ESTILC) 2018/2019 ORGANISING INSTITUTION ’S INFORMATION FORM NAME OF THE INSTITUTION : ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES ADDRESS : KREUTZWALDI 1, TARTU COUNTRY : ESTONIA ESTILC LANGUAGE LEVEL COURSES ORGANISED: LEVEL I (BEGINNER ) X LEVEL II (INTERMEDIATE ) NUMBER OF COURSES : 1 NUMBER OF COURSES : DATES : 08.08-24.08.2018 DATES : WEB SITE HTTPS :// WWW .EMU .EE /EN /ADMISSION S/EXCHANGE -STUDIES /ERASMUS / PLEASE NOTE THAT ALL STUDENT APPLICATIONS FOR OUR ESTILC COURSE SHOULD BE SENT BY E -MAIL TO THE FOLLOWING ADDRESS : APPLICATION DEADLINE 31.05.2018 STAFF JOB TITLE / NAME ADDRESS , TELEPHONE , FAX , E-MAIL CONTACT PERSON ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES FOR ESTILC KREUTZWALDI 56/1, 51014 TARTU /E STONIA LIISI VESKE PHONE : +372 731 3174 JOB TITLE FAX : +372 731 3037 PROGRAMME COORDINATOR E-MAIL : LIISI .V ESKE @EMU .EE ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES KREUTZWALDI 56/1, 51014 TARTU /E STONIA RESPONSIBLE PERSON FOR THE PROGRAMME PHONE : +372 731 3174 FAX : +372 731 3037 LIISI VESKE E-MAIL : LIISI .V ESKE @EMU .EE PART I: GENERAL INFORMATION • DESCRIPTION OF TOWN - SHORT HISTORY AND LOCATION 1 Tartu is the second largest city of Estonia. Tartu is located 185 kilometres to south from the capital Tallinn. Tartu is known also as the centre of Southern Estonia. The Emajõgi River, which connects the two largest lakes (Võrtsjärv and Peipsi) of Estonia, flows for the length of 10 kilometres within the city limits and adds colour to the city. As Tartu has been under control of various rulers throughout its history, there are various names for the city in different languages. -

Overview of the Use and Preservation of State Assets in 2006

Overview of the Use and Preservation of State Assets in 2006 Auditor General’s summary of observations made during the year NAO’s report to the Parliament, Tallinn, 2007 Overview of the Use and Preservation of State Assets in 2006 Overview of the Use and Preservation of State Assets in 2006 Auditor General’s summary of observations made during the year Foreword by the Auditor General This overview summarises a part of the work of the National Audit Office (“NAO”) in auditing the state assets in 2006 and 2007. The overview presents a selection of problems associated with state assets and their management, which in the opinion of the NAO require special attention of the Parliament and the public. Specific information on the implementation of the 2006 budget, government accounting procedures and reporting can be obtained from the consolidated annual report of the state and the evaluation of this report by the NAO. The examples provided in the Overview are presented to illustrate the problems. The report of the NAO includes only a small part of the observations made during the audits and the ministries should not use this as a comparison base in managing state assets. The audit reports underlying this overview are available in full on our web site www.riigikontroll.ee. The aim of the NAO is to help the state to be a good manager. The independent information provided by the NAO helps the Parliament to enhance the efficiency of the parliamentary control. The need for parliamentary control has been also emphasised by the Parliament through the formation of a separate committee for cooperation with the NAO and the Government of the Republic. -

Programme Handbook 1

Tartu, Estonia 8 - 10 August 2017 Programme handbook 1 Contents Programme ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Abstracts ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Invited speakers .................................................................................................................................. 6 Participants ....................................................................................................................................... 17 Practical information ............................................................................................................................ 38 Directions .............................................................................................................................................. 44 Contacts of local organizers .................................................................................................................. 46 Maps of Tartu ........................................................................................................................................ 47 Programme Monday, August 7th 16:00 – 20:00 Registration of participants Estonian Biocentre, Riia 23b 20:00 – 22:00 Welcome reception & BBQ Vilde Ja Vine restaurant, Vallikraavi 4 Tuesday, August 8th 08:45 – 09:35 Registration of participants Estonian Biocentre, Riia 23b 9:35 -

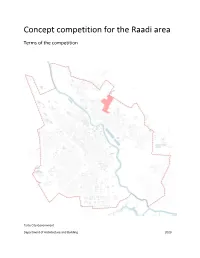

Concept Competition for the Raadi Area

Concept competition for the Raadi area Terms of the competition Tartu City Government Department of Architecture and Building 2020 Table of contents 1. Objective, competition area and contact area of the concept competition .......................................................... 3 2. History .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Detailed plans and architectural plans in effect for the area ................................................................................. 7 4. Streets of the competition area ........................................................................................................................... 11 5. Environment and landscaping .............................................................................................................................. 12 6. Competition task by properties ........................................................................................................................... 13 7. Organisation of the competition .......................................................................................................................... 17 7.1 Organiser of the competition ........................................................................................................................ 17 7.2 Competition format ...................................................................................................................................... -

Presenting and Interpreting Medieval Saints Today in Canterbury, Durham and York

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 13 (1): 79–105 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2019-0005 “THE NARRATIVE IS AMBIGUOUS AND THAT LOCATION ISN’T THE RIGHT LOCATION”: PRESENTING AND INTERPRETING MEDIEVAL SAINTS TODAY IN CANTERBURY, DURHAM AND YORK TIINA SEPP PhD, Research Fellow Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore Institute for Cultural Research and Fine Arts University of Tartu Ülikooli 18, 50090 Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Drawing on research for the Pilgrimage and England’s Cathedrals, Past and Pre- sent project, this article explores how the project’s medieval case study cathedrals – Canterbury, Durham and York – present their saints and shrines, and how visitors react to and interpret them. While looking at various narratives – predominantly about saints in historical and contemporary contexts – attached to these cathedrals, I also aim to offer some glimpses into how people interact with and relate to space. I argue that beliefs and narratives about saints play a significant role in the pil- grimage culture of the cathedral. I will also explore how the lack of a clear central narrative about the saint leaves a vacancy that will be filled with various other narratives. KEYWORDS: saints • cathedrals • pilgrimage • Canterbury • Durham • York INTRODUCTION This article* will explore how three medieval cathedrals – Canterbury, Durham and York – present their saints and shrines, and how visitors react to and interpret them. * This research was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (grant num- ber AH/ L015005/1). The article is based on research conducted between 2014 and 2018 for the Pilgrimage and England’s Cathedrals, Past and Present interdisciplinary research project. -

Tartu Handbook

1 A Short Guide to Living in Tartu, Estonia This guide was written by a Nebraska Wesleyan University (NWU) professor and Fulbright Scholar who taught at the University of Tartu from August 2011 – June 2012. The opinions expressed here are those of the professor, her husband and children (ages 12 and 8) who made discoveries about what to bring, where to eat and which Estonian phrases to master through trial and error. Their opinions do not reflect those of the US State Department or NWU. This guide is designed to supplement the materials students receive from NWU and the University of Tartu, and those that scholars receive from the US State Department and the American Embassy in Tallinn. What to Bring Euros (about 300€ to get started) A credit card with no currency exchange fees Umbrella Winter coat, scarf, hat, mittens, water-proof boots (woolens can be purchased here, see below) Excellent walking shoes (Estonians wear sneakers, but not bright white ones) Insect repellant (only spring semester) Any brand name personal item that you cannot live without (deodorant, shampoo, feminine hygiene products, contact lens solution, etc.) These products are widely available here, but in fewer brands. Peanut butter (If you happen to love it. You will not find any American peanut butter here). Laptop (you will find free Wi Fi nearly everywhere) An E-reader to easily purchase English language books Meghan K. Winchell [email protected] June 2012 2 Taking the Bus from Tallinn Airport to Tartu Arrive at the airport. Collect your luggage. Exit the airport. Walk to the Takso (taxi) stand. -

Newcomers Guide

Baltic Defence College Ad Securitatem Patriarum NEWCOMERS GUIDE 1 Contents Baltic Defence College 3 BALTDEFCOL practical information 5 Arrival to Estonia 8 Facts about Estonia 9 Economy 11 E-Estonia 11 Culture 11 Music 11 Visual Arts 12 Literature 12 Theatre 12 Film 12 Right of Residence and residence Permits 13 Health Insurance 13 Health Care System 14 Tartu 17 Getting around 17 Communications 19 Day Care Centres and Schools 20 After School Activities for Youth 21 Organisations 21 Leisure time 22 Health and Fitness 24 Stores and services 25 Public Holidays 28 Glossary 29 Contact Information 30 2 Baltic Defence College The Baltic Defence College (BALTDEFCOL) is a modern, future-oriented, English-language based international institution of the Baltic States providing professional military education with a Baltic regional focus and Euro-Atlantic scope. The college serves as a professional military education institution at the operational and strategic level, applying contemporary educational principles, effective management and best use of intellectual and material resources. Our mission is to educate military and security/defence related civilian personnel of the Baltic States as well as their NATO/EU allies and other partners, to contribute to applied research focused on security and defence policies while promoting international cooperation and networking. Our educational program consists of four residential courses: the Senior Leaders Course at the strategic-political level, the Higher Command Studies Course at the strategic level and the Joint Command and General Staff Course as well as the Civil Servants Course, both at the operational level. In addition, BALTDEFCOL hosts and co-hosts international conferences and seminars and conducts applied research. -

1 University of Tartu Ülikooli 18, Tartu 50090 Estonia

ESTONIAN LANGUAGE AND CULTURE COURSE (ESTILC) 2018/2019 ORGANISING INSTITUTION’S INFORMATION FORM NAME OF THE INSTITUTION: UNIVERSITY OF TARTU ADDRESS: ÜLIKOOLI 18, TARTU 50090 COUNTRY: ESTONIA ESTILC LANGUAGE ESTONIAN LEVEL COURSES ORGANISED: LEVEL I (BEGINNER) LEVEL II (INTERMEDIATE) NUMBER OF COURSES: 1 NUMBER OF COURSES: DATES: 07.01-25.01.2019 DATES: WEB SITE www.maailmakeeled.ut.ee/en/estilc PLEASE NOTE THAT ALL STUDENT APPLICATIONS FOR OUR ESTILC COURSE SHOULD BE SENT BY E-MAIL TO THE FOLLOWING ADDRESS: [email protected] APPLICATION DEADLINE 15.11.2018 STAFF JOB TITLE / NAME ADDRESS, TELEPHONE, FAX, E-MAIL CONTACT PERSON FOR ESTILC LOSSI 3-410 KÄTLIN LEHISTE TARTU 51003 JOB TITLE ESTONIA ESTILC COORDINATOR / ASSISTANT TO THE HEAD TEL (+372) 737 5358 [email protected] RESPONSIBLE PERSON FOR THE PROGRAMME LOSSI 3-411 KERSTI LEPAJÕE TARTU 51003 DIRECTOR ESTONIA UNIVERSITY OF TARTU TEL (+372) 737 5356 COLLEGE OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES AND CULTURES [email protected] PART I: GENERAL INFORMATION DESCRIPTION OF TOWN - SHORT HISTORY AND LOCATION 1 Tartu is the second largest city of Estonia. In contrast to the political and financial capital Tallinn, Tartu is often considered the intellectual and cultural hub, especially since it is the home to oldest and most renowned university in Estonia. Situated 186 km southeast of Tallinn, the city is the centre of southern Estonia. The Emajõgi river, which connects the two largest lakes of Estonia, crosses Tartu. The city is served by Tartu airport. Historical names of the town include Tarbatu, after an Estonian fortress founded in the 5th century, Yuryev (Russian: Юрьев) named c.