A Revisionist Analysis of Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 18, 2014 (Series 28: 4) Satyajit Ray, CHARULATA (1964, 117 Minutes)

February 18, 2014 (Series 28: 4) Satyajit Ray, CHARULATA (1964, 117 minutes) Directed by Satyajit Ray Written byRabindranath Tagore ... (from the story "Nastaneer") Cinematography by Subrata Mitra Soumitra Chatterjee ... Amal Madhabi Mukherjee ... Charulata Shailen Mukherjee ... Bhupati Dutta SATYAJIT RAY (director) (b. May 2, 1921 in Calcutta, West Bengal, British India [now India]—d. April 23, 1992 (age 70) in Calcutta, West Bengal, India) directed 37 films and TV shows, including 1991 The Stranger, 1990 Branches of the Tree, 1989 An Enemy of the People, 1987 Sukumar Ray (Short documentary), 1984 The Home and the World, 1984 (novel), 1979 Naukadubi (story), 1974 Jadu Bansha (lyrics), “Deliverance” (TV Movie), 1981 “Pikoor Diary” (TV Short), 1974 Bisarjan (story - as Kaviguru Rabindranath), 1969 Atithi 1980 The Kingdom of Diamonds, 1979 Joi Baba Felunath: The (story), 1964 Charulata (from the story "Nastaneer"), 1961 Elephant God, 1977 The Chess Players, 1976 Bala, 1976 The Kabuliwala (story), 1961 Teen Kanya (stories), 1960 Khoka Middleman, 1974 The Golden Fortress, 1973 Distant Thunder, Babur Pratyabartan (story - as Kabiguru Rabindranath), 1960 1972 The Inner Eye, 1972 Company Limited, 1971 Sikkim Kshudhita Pashan (story), 1957 Kabuliwala (story), 1956 (Documentary), 1970 The Adversary, 1970 Days and Nights in Charana Daasi (novel "Nauka Doobi" - uncredited), 1947 the Forest, 1969 The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha, 1967 The Naukadubi (story), 1938 Gora (story), 1938 Chokher Bali Zoo, 1966 Nayak: The Hero, 1965 “Two” (TV Short), 1965 The (novel), 1932 Naukadubi (novel), 1932 Chirakumar Sabha, 1929 Holy Man, 1965 The Coward, 1964 Charulata, 1963 The Big Giribala (writer), 1927 Balidan (play), and 1923 Maanbhanjan City, 1962 The Expedition, 1962 Kanchenjungha, 1961 (story). -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara ISSN: 2469-0783 [email protected] Fundación MenteClara Argentina Basu, Ratan Lal Tagore-Ocampo relation, a new dimension Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara, vol. 3, no. 2, 2018, April-September 2019, pp. 7-30 Fundación MenteClara Argentina DOI: https://doi.org/10.32351/rca.v3.2.43 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=563560859001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Tagore-Ocampo relation, a new dimension Ratan Lal Basu Artículos atravesados por (o cuestionando) la idea del sujeto -y su género- como una construcción psicobiológica de la cultura. Articles driven by (or questioning) the idea of the subject -and their gender- as a cultural psychobiological construction Vol. 3 (2), 2018 ISSN 2469-0783 https://datahub.io/dataset/2018-3-2-e43 TAGORE-OCAMPO RELATION, A NEW DIMENSION RELACIÓN TAGORE-OCAMPO, UNA NUEVA DIMENSIÓN Ratan Lal Basu [email protected] Presidency College, Calcutta & University of Calcutta, India. Cómo citar este artículo / Citation: Basu R. L. (2018). « Tagore-Ocampo relation, a new dimension». Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara, 3(2) abril-septiembre 2018, 7-30. DOI: 10.32351/rca.v3.2.43 Copyright: © 2018 RCAFMC. Este artículo de acceso abierto es distribuido bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial (by-cn) Spain 3.0. Recibido: 23/05/2018. -

'Nastanirh' of Rabindranath Tagore

INTERNATIONALJOURNALOF MULTIDISCIPLINARYEDUCATIONALRESEARCH ISSN:2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR :6.514(2020); IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286 Peer Reviewed and Refereed Journal: VOLUME:10, ISSUE:1(3), January :2021 Online Copy Available: www.ijmer.in FEMININE PSYCHOLOGY IN THE SHORT STORY “NASTANIRH” OF RABINDRANATH TAGORE Dr.Biva Rani Das Assistant Professor Dhakuakhana College, Dhakuakhana, Assam The Abstract Female characters have played an important role in the short stories of Rabindranath Tagore. The female characters of his short stories are more prominent than the male characters. Most of his stories are centred round the endless problems and contradictions faced by the females. “Nastanirh”, a short story by Rabindranath, has been regarded as one of the best short stories ever. The short story titled “Nastanirh” was published in 1308 Bangabda in the Baishakh-Agrahayan issue of a magazine named “Bharati”. (Majumdar, Samaresh, p 150). Feminist ideals have been perfectly reflected in the short story. The eternal fact of dominance over the inner minds of females has been vividly exposed. The complex male-female relationship is aptly portrayed in this short story by means of psycho- analytic descriptions. In this Research paper, we are going to present a discussion on the topic of “Feminine psychology in the short story “Nastanirh” of Rabindranath Tagore.” Keywords: Feminine, Male, Psychology, Nastanirh, Rabindranath, Charu, Bhupati. Introduction: The plot of the short-story is about the scenario of the degraded conjugal life of Charulata and Bhupati. Bhupati couldn’t manage time to stay with his new wed young wife due to his hectic preparations of publishing a newspaper. -

Barrenness and Bengali Cinema

1 “May You Be the Mother of A Hundred Sons!”: Barrenness vs. Motherhood in Bengali Cinema” Somdatta Mandal Department of English & Other Modern European Languages Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Borrowing from the recently published novel The Palace of Illusions, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s reimagining of the world-famous epic Mahabharata, let me begin with a well-known story. “Gandhari’s marriage, although she’d given up so much for its sake, was – like Kunti’s – not a happy one. Dhritarashtra was a bitter man. He never got over the fact that he’d been passed over by the elders – just because he was blind – when they decided which of the brothers should be king… The goal of Dhritarashtra’s life was to have a son who could inherit the throne after him. But here a problem arose, for in spite of his assiduous attempts Gandhari didn’t conceive for many years. When she finally did, it was too late. Kunti was already pregnant with Judhisthir. A year came. A year went. Yudhisthir was born. As the first male child of the next generation, the elders declared, the throne would be his. Dhritarashtra’s spies brought more bad news. Kunti was pregnant again. Now there were two obstacles between Dhritarashtra and his desire. Gandhari’s stomach grew large as a giant beehive, but her body refused to go into labor. Perhaps the frustrated king berated her, or perhaps the fact that he’d taken one of her waiting women as his mistress drove Gandhari to her act of desperation. She struck her stomach again and again until she bled, and bleeding gave birth to a huge, unformed ball of flesh. -

Paper 14; Module 25; E Text (A) Personal Details

Paper 14; Module 25; E Text (A) Personal Details Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator Prof. Tutun University of Hyderabad Mukherjee Paper Coordinator Prof. Asha Kuthari Guwahati University Chaudhuri, Content Writer/Author Ananya Guwahati University (CW) Bhattacharjee Content Reviewer (CR) Dr. Farddina Dept. of English, Guwahati Hussain University Language Editor (LE) Dr. Dolikajyoti Assistant Professor, Guwahati Sharma, University (B) Description of Module Item Description of module Subject Name English Paper name Indian Writing in English Module title Rabindranath Tagore: Gora Module ID MODULE 25 Module 25 Rabindranath Tagore-Gora Introducing the Author Rabindranath Tagore is a major presence when one thinks of Bengal and its culture; a paramount figure in Bengali literature. A collection of poems, Gitanjali (Song Offerings), secured for him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913. He excelled in various genres of art and culture and became renowned as a poet, dramatist, novelist, composer, actor, singer, editor of the Bengali literary journal (Sadhana). He composed more than 2000 poems and 3000 songs. As a literary genius he had deep knowledge of the society of his days and was a staunch lover of nature. Tagore founded Shantiniketan in a natural surrounding thereby giving vent to his passion for nature and a new education system. It is common knowledge that Tagore was absorbed in the world of words and his imaginative world resulted in the production of a great number of novellas, songs, poetry and plays. During pre–independence times, Tagore travelled to various places to perform and collect funds for the establishment of his university (Vishvabharati). It was during those days that his troupe staged a dance-drama, Notir Puja, based on a story he had written and it was later filmed in 1932 by New Theatres. -

Rabindranath Tagore - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Rabindranath Tagore - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Rabindranath Tagore(7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) Rabindranath Tagore (Bengali: ??????????? ?????) sobriquet Gurudev, was a Bengali polymath who reshaped his region's literature and music. Author of Gitanjali and its "profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse", he became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. In translation his poetry was viewed as spiritual and mercurial; his seemingly mesmeric personality, flowing hair, and other-worldly dress earned him a prophet-like reputation in the West. His "elegant prose and magical poetry" remain largely unknown outside Bengal. Tagore introduced new prose and verse forms and the use of colloquial language into Bengali literature, thereby freeing it from traditional models based on classical Sanskrit. He was highly influential in introducing the best of Indian culture to the West and vice versa, and he is generally regarded as the outstanding creative artist of modern India. A Pirali Brahmin from Calcutta, Tagore wrote poetry as an eight-year-old. At age sixteen, he released his first substantial poems under the pseudonym Bhanusi?ha ("Sun Lion"), which were seized upon by literary authorities as long-lost classics. He graduated to his first short stories and dramas—and the aegis of his birth name—by 1877. As a humanist, universalist internationalist, and strident anti- nationalist he denounced the Raj and advocated independence from Britain. As an exponent of the Bengal Renaissance, he advanced a vast canon that comprised paintings, sketches and doodles, hundreds of texts, and some two thousand songs; his legacy endures also in the institution he founded, Visva- Bharati University Tagore modernised Bengali art by spurning rigid classical forms and resisting linguistic strictures. -

Tagore Studies

TAGORE STUDIES PREAMBLE Tagore Studies will be a mainly Activity, Presentation and Seminar-based Learner-Centric Course that will offer the option of taking it up as a Minor Discipline (all six courses for 18 Credits) or One-at-a-time Course (3 Credits) under Open Elective Choice where the participants would be able to engage themselves in Making a Choice, as to which Course/Courses to opt for (for instance, someone from Fine Arts and Aesthetics background may like to opt for ‗Tagore as a Culture Icon with special reference to his Painting‘ or ‗Tagore and Mass Media,‘ whereas a Literature candidate may like to go for ‗Tagore as a Poet‘ and ‗Tagore as a Fiction Writer.‘ Students enrolled in Mass Media and Communication may love to get connected to ‗Tagore and Mass Media‘ as well as ‗Tagore as a Fiction Writer.‘ Those from the History orientation may like to opt for the ‗Cultural History‘ area under ‗Tagore as a Cultural Icon‘ module). Collaboration within or across disciplines to create a joint appraisal/critique/text which could then be presented before the class for internal evaluation – by the faculty and remaining students together – in a peer review mode together.) Communication would be tested on the oral or ppt presentations that a participant may like to make on any aspect of Tagore in a Colloquium model where one person communicates and the others on the panel comment, agree, differ or substantiate etc where their performance is evaluated. Critical thinking with respect to the issues raised by Tagore in the areas on Religion, Societal Practices, Nation Building, or Politics (especially in ENG2652) on which a participant may like to write an end-semester Term Paper. -

Critiquing Rituparna Ghosh: Gender Sensitivity and Identity in Films

National Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development ISSN: 2455-9040 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.nationaljournals.com Volume 2; Issue 3; September 2017; Page No. 15-17 Critiquing Rituparna Ghosh: Gender sensitivity and identity in films Dr. Mehak Jonjua Assistant Professor, Amity University, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India Abstract Film maker, versifier and an author, Rituparna Ghosh was Bengali and Indian cinema’s agent provocateur and one of the most modern directors, having received both national and international acclaims for his films. He is credited for changing the Cinematic ideology, perception and impact especially for the Bengali middle class ‘bhadrolok’ and moved into narrative film making with the critically acclaimed Hirer Angti in 1992 and Unishey April in 1995. Apart from projecting Bengali culture and tradition, his concepts moved around the convolutions of relationships, the niceties of feelings and the often silent hardships that are involved in everyday family life in India. His work projects the changing perceptions of the ‘Gender Identity’ by dominant sensitized middle class with narratives of sexual desires, thereby demystifying existing philosophies of heteronormativity and heteropatriarchy. Keywords: films, gender identity and bhadralok Introduction controlled domestic eco-system in which they were tested, Ghosh came into scene when Bengali Cinema was wheezing tensions would mount, passions would play their turn and the for breath, having been heave down over nearly two decades. possibilities of melodrama were to be fully realized [1]. His stories were gasping for fresh breath full of creativity and new perspective. The paper is written to study the women Ghosh and Portrayal of Gender Identity in his Movies projection and characters that has always famed the female Arekti Premer Golpo was his first film after the sexuality and freedom and scuttled against the main principles decriminalization of 377. -

GENDER and NATION in SOUTH ASIAN FICTION a Dissertation

SACRED SUBJECTS: GENDER AND NATION IN SOUTH ASIAN FICTION A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Krupa Kirit Shandilya August 2009 © 2009 Krupa Kirit Shandilya SACRED SUBJECTS: GENDER AND NATION IN SOUTH ASIAN FICTION Krupa Kirit Shandilya, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 My dissertation, Sacred Subjects: Gender and Nation in South Asian Literature, intervenes in the ongoing debates in postcolonial and feminist studies about the mapping of woman onto nation. There has been a tendency to read the land as female in both colonial and postcolonial discourse. As feminist scholars like Anne McClintock have shown, such a mapping places the burden of representing the nation onto the gendered subject. My dissertation argues that fiction in Bengali, Urdu and English undoes this mapping by creating non-normative gendered figures implicated in the sacred, who counteract the paternalistic figurations of gender present in imperialist and nationalist discourse. My introductory chapter argues that the non-normative gendered figures of this fiction have been repressed by the nation-state in order to create a homogenous entity called the “nation.” My second chapter argues that late-nineteenth century Bengali domestic fiction, namely Bankimchandra Chatterjee’s Krishnakanta’s Will and The Poison Tree, Rabindranath Tagore’s Chokher Bali and Saratchandra Chatterjee’s Charitraheen and Srikanta, challenges the notion of the exploited Hindu widow who needs to be rescued from her plight, by creating the widow as an empowered character who usurps wifely devotion or satita, implicated in Hindu devotional practices, to create a space for herself within her society. -

Rabindranath Tagore - Interesting Facts You Can't Miss About the Legend's Life on His Birth Anniversary!

Rabindranath Tagore - Interesting Facts You Can't Miss About The Legend's Life on His Birth Anniversary! India's first Nobel laureate in Literature - Rabindranath Tagore was quite a polymath. His work ranged from poetry, painting, religious reformation, etc. Rabindranath Tagore was a visionary, creative soul to par excellence and the founder of the prominent educational institute Vishwa Bharti. On Rabindranath Tagore's birth anniversary which falls on 7th May, it is a pleasure to remember this great philosopher. Learning about this epic personality becomes important for you if you are preparing for any Government Recruitment Exams like IBPS RRB, RBI Grade B, SSC CGL, SSC CPO, Railways ALP, Railways Group D & more. This will help you in your General Awareness section of all these major exams. You can also download this as a PDF, Rabindranath Tagore - Introduction Rabindranath Tagore Native Name Robindronath Thakur Birth Date 7th May 1861 Birth Place Calcutta, British India Alma Mater University College London Spouse Mrinalini Devi Died 7th August 1941 (age 80) Rabindranath Tagore - Major Achievements Let’s take a tour of Rabindranath's life experiences and his contribution that still inspire generations after generation. • Rabindranath Tagore was the first Asian to make a mark by his astounding work in the field of Literature. • He was recognized by the Nobel Award in 1913. • He wrote soul-stirring poetry and even authored various fiction based books that are still considered the best pieces of Literature. 1 | P a g e • He had a great friendship with the father of the Nation - Mahatma Gandhi, and together their thoughts and ideas influenced many revolutionaries. -

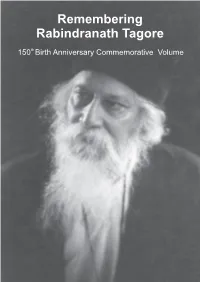

Remembering Rabindranath Tagore Volume

Remembering Rabindranath Tagore 150th Birth Anniversary Commemorative Volume Compiled and edited by Sandagomi Coperahewa University of Colombo High Commission of India, Colombo Indian Cultural Centre, Colombo India-Sri Lanka Foundation, Colombo University of Colombo Cover Portrait of Tagore taken while he was in Sri Lanka in 1934. Courtesy : Rabindra Bhavana, Santiniketan. Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of the High Commission of India, the Indian Cultural Centre and the University of Colombo. Published by University of Colombo 2011 Printer Softwave Printing & Packaging (Pvt) Ltd. 107 D, Havelock Road, Colombo 05. Contents Message from His Excellency the President of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka Message from His Excellency the High Commissioner of India Message from the Vice Chancellor, University of Colombo Introduction Page 1. Tagore and Sri Lanka: The Highlights of an Abiding Relationship 01 K.N.O. Dharmadasa 2. “ The Inside Story” : Gender and Modernity in Chokher Bali 08 Radha Chakaravarty 3. A South Asian Alter-realism: Tagore's Art of Short Story (in Sinhala) 15 Liyanage Amarakeerti 4. The Musical Journey of Rabindranath Tagore 32 Reba Som 5. An Insight into the Impact of Rabindranath Tagore on Sinhala Art 39 and Music Sunil Ariyaratne 6. Bengali Renaissance, Tagore and Sri Lanka (in Sinhala) 48 Chintaka Ranasinghe 7. Nationalism and National Freedom: Tagore’s Perspective 71 Nirosha Paranavitana 8. Modern Sinhala Literary Arts Discourse and 81 Rabindranath Tagore (in Sinhala) Sarath Wijesooriya 9. Philosophy of Humanistic Universalism of Rabindranath Tagore 91 (in Tamil) Mallika Rajaratnam 10. Educational Thoughts of Tagore (in Sinhala) 97 Piyal Somaratne 11. -

Chokher Bali (Binodini) : a Protest of Rabindranath Tagore

International Journal of Innovative Studies in Sociology and Humanities (IJISSH) ISSN 2456-4931 (Online) www.ijissh.org Volume: 3 Issue: 7 | July 2018 Chokher Bali (Binodini) : A Protest of Rabindranath Tagore Manas Saha Assistant Professor, Department of English, Nabagram Amar Chand Kundu College, Kalyani - University, West Bengal, India Abstract: Rabindranath Tagore is a versatile genius for his works which consist of poems, short stories, dramas, novels, paintings, music etc. Many contemporary issues like social problem, political restlessness, religious violence, patriotism, psychological conflict, woeful conditions of women and the ultimate emergence of new women were brought to a focus in his writings. Tagore was a social reformer, philosopher, and prophet. His books and essays on philosophy, literature, religion, education, and social topics discussed not only the contemporary issues but also illuminated how to get emancipation from social problems. The social condition of women of his time, their deprivation in every sphere of society touched Tagore. Tagore protested against that social order and wrote for the oppressed women their position in society. In this paper, my attempt is to find out Tagore’s feminist point of view and sympathy for women through his female protagonist Binodini in the novel, “Chokher Bali”( 1903). Keywords: Contemporary society, Women, Widow, Protest, Emancipation. 1. INTRODUCTION Society creates literature. It may be described as the mirror of the society. If literature expresses social sympathies, naturally it is bound to exercise some positive influence on human mind and attitude. Society reacts to literature in a living way. It rouses feelings and enthusiasm for welfare. Tagore’s different experiences in western countries, perception, knowledge and political experiences and generosity reshaped and reacted against the oppression of women in the patriarchal society of his time.