Recurrent Discitis in the Acute Rehab Setting: a Case Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

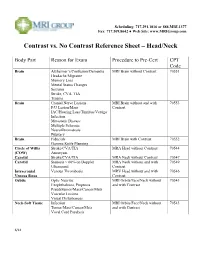

Contrast Vs. No Contrast Reference Sheet – Head/Neck

Scheduling: 717.291.1016 or 888.MRI.1377 Fax: 717.509.8642 ● Web Site: www.MRIGroup.com Contrast vs. No Contrast Reference Sheet – Head/Neck Body Part Reason for Exam Procedure to Pre-Cert CPT Code Brain Alzheimer’s/Confusion/Dementia MRI Brain without Contrast 70551 Headache/Migraine Memory Loss Mental Status Changes Seizures Stroke, CVA, TIA Trauma Brain Cranial Nerve Lesions MRI Brain without and with 70553 F/U Lesion/Mass Contrast IAC/Hearing Loss/Tinnitus/Vertigo Infection Metastatic Disease Multiple Sclerosis Neurofibromatosis Pituitary Brain Fiducials MRI Brain with Contrast 70552 Gamma Knife Planning Circle of Willis Stroke/CVA/TIA MRA Head without Contrast 70544 (COW) Aneurysm Carotid Stroke/CVA/TIA MRA Neck without Contrast 70547 Carotid Stenosis > 60% on Doppler MRA Neck without and with 70549 Ultrasound Contrast Intracranial Venous Thrombosis MRV Head without and with 70546 Venous Sinus Contrast Orbits Optic Neuritis MRI Orbits/Face/Neck without 70543 Exophthalmos, Proptosis and with Contrast Pseudotumor/Mass/Cancer/Mets Vascular Lesions Visual Disturbances Neck-Soft Tissue Infection MRI Orbits/Face/Neck without 70543 Tumor/Mass/Cancer/Mets and with Contrast Vocal Cord Paralysis 6/14 Scheduling: 717.291.1016 or 888.MRI.1377 Fax: 717.509.8642 ● Web Site: www.MRIGroup.com Contrast vs. No Contrast Reference Sheet – Spine Body Part Reason for Exam Procedure to Pre-Cert CPT Code Spine: Cervical Degenerative Disease MRI Cervical Spine without Contrast 72141 Disc Herniation Extremity Pain/Weakness Neck Pain Radiculopathy Trauma Spine: -

Cervical Neck Pain Or Cervical Radiculopathy

Revised 2018 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Cervical Neck Pain or Cervical Radiculopathy Variant 1: New or increasing nontraumatic cervical or neck pain. No “red flags.” Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level Radiography cervical spine Usually Appropriate ☢☢ MRI cervical spine without IV contrast May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) O CT cervical spine without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT cervical spine with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ MRI cervical spine without and with IV Usually Not Appropriate contrast O CT cervical spine without and with IV Usually Not Appropriate contrast ☢☢☢ CT myelography cervical spine Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ CTA neck with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ Discography cervical spine Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢ Facet injection/medial branch block cervical Usually Not Appropriate spine ☢☢ MRA neck with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRA neck without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI cervical spine with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O Bone scan whole body with SPECT or Usually Not Appropriate SPECT/CT neck ☢☢☢ X-ray myelography cervical spine Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Cervical Neck Pain or Cervical Radiculopathy Variant 2: New or increasing nontraumatic cervical radiculopathy. No “red flags.” Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level MRI cervical spine without IV contrast Usually Appropriate O CT cervical spine without IV contrast -

Acute Calcific Discitis with Intravertebral Disc Herniation in the Dorsolumbar Spine

Published online: 2021-08-02 MUSCULOSKELETAL Case report: Acute calcific discitis with intravertebral disc herniation in the dorsolumbar spine Puneet Mittal, Kavita Saggar, Parambir Sandhu, Kamini Gupta Department of Radiodiagnosis, Dayanand Medical College & Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab, India Correspondence: Dr. Puneet Mittal, Department of Radiodiagnosis, Dayanand Medical College & Hospital, Tagore Nagar, Civil Lines, Ludhiana, Punjab - 141 001, India. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Acute calcific discitis is a rare but well-known condition of unknown etiology. In symptomatic cases, the most common site is the cervical spine. We describe the CT scan and MRI findings in a symptomatic patient, with a lesion in the dorsolumbar spine. Key words: Acute; calcific; discitis; dorsolumbar; MR Introduction Acute calcifc discitis is a rare condition. When symptomatic, it can be mistaken for infection.[1] Most of the symptomatic cases present in the cervical spine.[1-3] We present the CT scan and MRI findings in a patient who had involvement of the dorsolumbar spine, with associated intravertebral disc herniation. Case Report A 10-year-old boy presented with a 2-week history of pain in the lower back following a yoga session in school. The pain had gradually worsened over the last 5 days. The patient was afebrile. The total white blood cell (WBC) count was normal. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was raised (52 mm/h). The Mantoux test was negative. A radiograph obtained elsewhere and repeated a day after the MRI [Figure 1], showed calcification of the D12-L1 intervertebral disc. MRI showed hypointense signal in the D12-L1 intervertebral disc on T1W [Figure 2A] and T2W [Figure 2B and C] images. -

Cervical Spondylodiscitis in an Infant with Torticollis

Cervical Spondylodiscitis in IMAGES IN CLINICAL an Infant with Torticollis RADIOLOGY BRECHT VAN BERKEL KRISTIN SUETENS LUC BREYSEM *Author affiliations can be found in the back matter of this article ABSTRACT CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Brecht Van Berkel Teaching point: Narrowing of the intervertebral space and destruction of the adjacent UZ Leuven, BE vertebral end plates on conventional radiography or CT should raise suspicion for brecht.vanberkel@student. spondylodiscitis in symptomatic infants. kuleuven.be KEYWORDS: Spondylodiscitis; MRI; pediatric; torticollis; cervical; CT TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Van Berkel B, Suetens K, Breysem L. Cervical Spondylodiscitis in an Infant with Torticollis. Journal of the Belgian Society of Radiology. 2021; 105(1): 35, 1–4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ jbsr.2454 Van Berkel et al. Journal of the Belgian Society of Radiology DOI: 10.5334/jbsr.2454 2 CASE REPORT disc space and loss of height of vertebral bodies C3 and C4 and irregular alignment of the end plates. On An eight-month-old infant presented at the emergency the sagittal T1-weighted Short-tau inversion-recovery department with a history of torticollis for six weeks. (STIR) images, the hyperintense signal in the vertebral Blood results showed no elevated inflammatory bodies of C3 and C4, as well as in the surrounding tissues parameters. Vertical lateral X-ray of the cervical spine (arrowheads) were compatible with a widespread area demonstrated a kyphotic angulation at the level of C3– of bone and soft tissue oedema (Figure 2). There were C4, narrowing of the intervertebral disc space, irregular no diffusion-restricted areas and no accompanying fluid end plates, and loss of height of the vertebral body of collections. -

Cervical Radiculopathy Clinical Guidelines for Medical Necessity Review

Cervical Radiculopathy Clinical Guidelines for Medical Necessity Review Version: 3.0 Effective Date: November 13, 2020 Cervical Radiculopathy (v3.0) © 2020 Cohere Health, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 2 Important Notices Notices & Disclaimers: GUIDELINES SOLELY FOR COHERE’S USE IN PERFORMING MEDICAL NECESSITY REVIEWS AND ARE NOT INTENDED TO INFORM OR ALTER CLINICAL DECISION MAKING OF END USERS. Cohere Health, Inc. (“Cohere”) has published these clinical guidelines to determine medical necessity of services (the “Guidelines”) for informational purposes only, and solely for use by Cohere’s authorized “End Users”. These Guidelines (and any attachments or linked third party content) are not intended to be a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment directed by an appropriately licensed healthcare professional. These Guidelines are not in any way intended to support clinical decision making of any kind; their sole purpose and intended use is to summarize certain criteria Cohere may use when reviewing the medical necessity of any service requests submitted to Cohere by End Users. Always seek the advice of a qualified healthcare professional regarding any medical questions, treatment decisions, or other clinical guidance. The Guidelines, including any attachments or linked content, are subject to change at any time without notice. ©2020 Cohere Health, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Other Notices: CPT copyright 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. -

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Clinical Guidelines for Medical Necessity Review

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Clinical Guidelines for Medical Necessity Review Version: 4.0 Effective Date: November 13, 2020 Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (v4.0) © 2020 Cohere Health, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Important Notices Notices & Disclaimers: GUIDELINES SOLELY FOR COHERE’S USE IN PERFORMING MEDICAL NECESSITY REVIEWS AND ARE NOT INTENDED TO INFORM OR ALTER CLINICAL DECISION MAKING OF END USERS. Cohere Health, Inc. (“Cohere”) has published these clinical guidelines to determine medical necessity of services (the “Guidelines”) for informational purposes only, and solely for use by Cohere’s authorized “End Users”. These Guidelines (and any attachments or linked third party content) are not intended to be a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment directed by an appropriately licensed healthcare professional. These Guidelines are not in any way intended to support clinical decision making of any kind; their sole purpose and intended use is to summarize certain criteria Cohere may use when reviewing the medical necessity of any service requests submitted to Cohere by End Users. Always seek the advice of a qualified healthcare professional regarding any medical questions, treatment decisions, or other clinical guidance. The Guidelines, including any attachments or linked content, are subject to change at any time without notice. ©2020 Cohere Health, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Other Notices: CPT copyright 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. Guideline Information: Specialty Area: Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (M00-M99) CarePath Group: Spine CarePath Name: Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (M48) Physician author: Mandy Armitage, MD (Sports Medicine) Peer reviewed by: Adrian Thomas, MD (Orthopedic Spine Surgeon) Literature review current through: June 22, 2020 Document last updated: November 13, 2020 Type: [X] Adult (18+ yo) | [_] Pediatric (0-17yo) Page 2 of 57 Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (v4.0) © 2020 Cohere Health, Inc. -

Tuberculous Spondylodiscitis in A

ISSN: 2474-3658 Mangouka et al. J Infect Dis Epidemiol 2019, 5:083 DOI: 10.23937/2474-3658/1510083 Volume 5 | Issue 4 Journal of Open Access Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology RESEARCH ARTICLE Tuberculous Spondylodiscitis in a Military Hospital in Gabon: Report of Eleven Patients Mangouka Guingali Laurette1, Iroungou Berthe A2, Bivigou-Mboumba Berthold3*, Oura Landry4, Mwanyombet Lucien4 and Nzenze Jean Raymond1 Check for 1Service de Médecine Interne, Hôpital d’Instruction des Armées Omar Bongo Ondimba (HIA OBO), Gabon updates 2École d’Application su Service de Santé Militaire de Libreville (EASSML), Gabon 3Unité mixte de Recherches sur le VIH et les Maladies Infectieuses Associées (UMR VIH-MIA), Centre Internationale de Recherche Médicale de Franceville (CIRMF), Gabon 4Service de Neurochirurgie, Hôpital d’Instruction des Armées Omar Bongo Ondimba (HIA OBO), Gabon *Corresponding authors: Dr. Bivigou-Mboumba Berthold, PhD, Unité mixte de Recherches sur le VIH et les Maladies Infectieuses Associées (UMR VIH-MIA), Centre Internationale de Recherche Médicale de Franceville (CIRMF), BP: 8507, Libreville, Gabon Abstract Background Background: Extrapulmonary forms of tuberculosis (TB) Tuberculosis (TB) is endemic in sub-Saharan Africa are on the rise in sub-Saharan Africa and pose a major and Asia [1]. It is caused by the Mycobacterium tuber- public health problem. The spine is the most frequent culosis and most commonly affects the lungs. However, location of musculoskeletal tuberculosis. Involvement of the spine causes severe back pain and weakness in the lower in TB endemic countries, extrapulmonary presentations extremities. We report 11 cases of TB spondylodiscitis, are reported frequently and include spinal tuberculo- commonly referred to as Pott's disease, who presented to sis, ganglionic tuberculosis, and urogenital involvement the internal medicine department at the Military Hospital of also known as Pott’s disease. -

What Is Sciatica All About YPO

WHAT IS SCIATICA ALL ABOUT ? Multimedia Health Education Disclaimer This movie is an educational resource only and should not be used to manage Sciatica. All decisions about the management of Sciatica must be made in conjunction with your Physician or a licensed healthcare provider. WHAT IS SCIATICA ALL ABOUT? Multimedia Health Education MULTIMEDIA HEALTH EDUCATION MANUAL TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION CONTENT 1 . Introduction a. What is Sciatica? b. Normal Spine Anatomy c. Sciatic Nerve Anatomy 2 . Overview of Sciatica a. Risk Factors b. Causes of Sciatica c. Symptoms of Sciatica d. Diagnosing Sciatica 3 . Treatment Options a. Conservative Treatment b. Surgical Treatment c. Post Operative Care d. Risks and Complications WHAT IS SCIATICA ALL ABOUT? Multimedia Health Education INTRODUCTION What is Sciatica? Sciatica is a painful condition caused by the irritation of the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve is the longest nerve in our bodies. It begins in the lower back and extends through the buttocks down the back of each leg to the thighs and feet. Sciatica can be acute (short term) lasting a few weeks, or chronic (long term) persisting for more than 3 months. It is important to understand that most Sciatica will resolve itself within a few weeks or months and rarely causes permanent nerve damage. To learn more about Sciatica, it is important to first understand normal spine anatomy and function. WHAT IS SCIATICA ALL ABOUT? Multimedia Health Education Unit 1: Normal Spine Anatomy Normal Spine Anatomy The spine, also called the back bone, is designed to give us stability, smooth movement, as well as providing a corridor of protection for the delicate spinal cord. -

Pathogenesis, Presentation, and Treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Associated with Coronal Or Sagittal Spinal Deformities

Neurosurg Focus 14 (1):Article 6, 2003, Click here to return to Table of Contents Pathogenesis, presentation, and treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis associated with coronal or sagittal spinal deformities JUSTIN F. FRASER, B.A., RUSSEL C. HUANG, M.D., FEDERICO P. GIRARDI, M.D., AND FRANK P. CAMMISA, JR., M.D. Hospital for Special Surgery; Bronx Veterans Affairs Hospital; and the Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, New York Sagittal- or coronal-plane deformity considerably complicates the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar spinal steno- sis. Although decompressive laminectomy remains the standard operative treatment for uncomplicated lumbar spinal stenosis, the management of stenosis with concurrent deformity may require osteotomy, laminectomy, and spinal fusion with or without instrumentation. Broadly stated, the surgery-related goals in complex stenosis are neural decom- pression and a well-balanced sagittal and coronal fusion. Deformities that may present with concurrent stenosis are scoliosis, spondylolisthesis, and flatback deformity. The presentation and management of lumbar spinal stenosis asso- ciated with concurrent coronal or sagittal deformities depends on the type and extent of deformity as well as its impact on neural compression. Generally, clinical outcomes in complex stenosis are optimized by decompression combined with spinal fusion. The need for instrumentation is clear in cases of significant scoliosis or flatback deformity but is controversial in spondylolisthesis. With appropriate selection of technique for deformity correction, a surgeon may profoundly improve pain, quality of life, and functional capacity. The decision to undertake surgery entails weighing risk factors such as age, comorbidities, and preoperative functional status against potential benefits of improved neu- rological function, decreased pain, and reduced risk of disease progression. -

Eikenella Corrodens (About the Left Side, with High Signal on T2/STIR Images and Low Sig- 10 Days After the Biopsy)

237 CASE REPORT Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pmj.79.930.237 on 1 April 2003. Downloaded from Unusual cause of infective discitis in an adolescent M K Sayana, A J Chacko,RCMcGivney ............................................................................................................................. Postgrad Med J 2003;79:237–238 The first case of infective discitis caused by Eikenella corro- dens in an adolescent is presented. The need for anaero- bic cultures when dealing with infective pathology in the spine is stressed. A 14 year old boy presented with acute exacerbation of back pain, which showed characteristics of infective discitis after magnetic resonance imaging. Computed tomography guided biopsy grew E corrodens in anaerobic cultures that was sensitive to ampicillin, co- amoxiclav, cefadroxil, and cefotaxime. This patient responded well to co-amoxiclav and recovered without any surgical intervention. ikenella corrodens is a slow growing, non-motile, faculta- tive Gram negative bacillus, which is a commensal of the oral cavity, and intestinal and genital tracts. There are E Figure 1 Oblique view of lumbar spine. case reports of adult spine infections (vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis)12 caused by eikenella, but none of spinal infection in children and adolescents.3 We report here the first case of discitis secondary to this organism in an adolescent. The various clinical manifestations caused by this organism include head and neck, pulmonary, intra-abdominal, cutane- ous, and skeletal infections, endocarditis, and pelvic abscess.4 Rare and interesting presentations like osteomyelitis in a chronic nail biter,5 osteomyelitis due to toothpick injury,67and http://pmj.bmj.com/ vertebral osteomyelitis due to pharyngeal injury caused by a fish bone2 have been reported. -

The Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Spinal Infections (Including Vertebral Osteomyelitis, Spondylodiscitis and Epidural Abscess)

MOJ Orthopedics & Rheumatology The Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Spinal Infections (Including Vertebral Osteomyelitis, Spondylodiscitis and Epidural Abscess) Introduction Editorial - Volume 4 Issue 3 - 2016 Spinal infection is becoming an increasingly prevalent con dition. However it is still often overlooked in the Casualty / ER department. As with most conditions, if it considered during the Royal Free Hospitals NHS Trust, UK diagnostic process, it is usually correctly diagnosed. Therefore the Corresponding author: Bob Chatterjee, Royal Free Hospitals toawareness investigate of theand condition diagnose needsthe condition to be promoted. correctly. This is a useful NHS Trust, Manor Lodge, 50a Green Lane, Burnham, South short article covering the salient points of the condition, and how Buckinghamshire, SL1 8EB, UK, Tel: 07970 903 269; 01628 313331; Email: Received: January 17, 2016 | Published: February 02, 2016 Discitis is the inflammation of the intervertebral discs caused by an infection. In most cases, it is a single disc involved although the infection can spread to adjacent discs. The condition is rare inbut elderly occurs patients more frequently as the discs in become children small than and adults. less likely It is tomore be- common in children between the ages of 2 and 7. It is more rare- III. History, e.g. history of cancer come inflamed with age. The common cause of discitis is second IV. Constitutional symptoms, such as fever, chills or unexplained ary infection from a remote source and the spread is through the weight loss anblood invasive stream. procedure Rarely, it such can asbe ainfection lumbar puncture,from the boneepidural that injec goes- down to the adjacent discs. -

Back Low Back Pain with Or Without Sciatica Pathway

Low Back Pain With or Without Sciatica Referral and Management Pathway Patient presents with low backPatient pain, nerve Presentation root or mechanical back pain, with or without leg pain symptoms. Are there ?:‘Red flag’ signs: Primary Care •First acute onset age <20 or >55 Provide reassurance, keep on the move, stay at work if possible. Address any additional •Non-mechanical pain No Red yellow flag signs: •Thoracic pain Flag Signs •PH-carcinoma, steroids, HIV •Attitudes & beliefs about back pain •Unwell, weight loss •Behaviour •Widespread neurology – unilateral or bilateral lower limb weakness and/or numbness •Compensation issues extending over several dermatomes •Diagnosis & treatment •Structural deformity, Trauma •Emotions www.nzgg.org.nz/guidelines/0072/acc1038_col.pdf •Consider Malignant Spinal Cord Compression •Family (page 40 onwards) •Acute Cauda Equina Syndrome signs: •Work •Dysfunction of bladder, bowel or sexual function •Sensory changes in saddle or perianal area Issue advice sheet. Meds as appropriate. Symptomatic measures: local cold pack (early •Discitis/infection symptoms: post-onset – care that skin protected & short duration e.g. 5-10 mins with minimum 2 hr •Sudden onset of acute spinal pain or suspicious change in pattern, no history of break) or heat (ensure skin protection e.g. through towelling and skin regularly checked). trauma Other forms of manual therapy (e.g. chiropractics) may be beneficial, however, these are •Systemic signs, fever, high pulse currently unavailable on the NHS. •Night pain Encourage self management.