Not All Cases of Neck Pain With/Without Torticollis Are Benign: Unusual Presentations in a Paediatric Accident and Emergency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

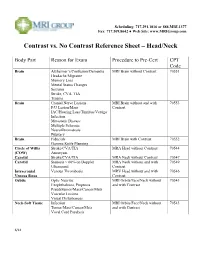

Contrast Vs. No Contrast Reference Sheet – Head/Neck

Scheduling: 717.291.1016 or 888.MRI.1377 Fax: 717.509.8642 ● Web Site: www.MRIGroup.com Contrast vs. No Contrast Reference Sheet – Head/Neck Body Part Reason for Exam Procedure to Pre-Cert CPT Code Brain Alzheimer’s/Confusion/Dementia MRI Brain without Contrast 70551 Headache/Migraine Memory Loss Mental Status Changes Seizures Stroke, CVA, TIA Trauma Brain Cranial Nerve Lesions MRI Brain without and with 70553 F/U Lesion/Mass Contrast IAC/Hearing Loss/Tinnitus/Vertigo Infection Metastatic Disease Multiple Sclerosis Neurofibromatosis Pituitary Brain Fiducials MRI Brain with Contrast 70552 Gamma Knife Planning Circle of Willis Stroke/CVA/TIA MRA Head without Contrast 70544 (COW) Aneurysm Carotid Stroke/CVA/TIA MRA Neck without Contrast 70547 Carotid Stenosis > 60% on Doppler MRA Neck without and with 70549 Ultrasound Contrast Intracranial Venous Thrombosis MRV Head without and with 70546 Venous Sinus Contrast Orbits Optic Neuritis MRI Orbits/Face/Neck without 70543 Exophthalmos, Proptosis and with Contrast Pseudotumor/Mass/Cancer/Mets Vascular Lesions Visual Disturbances Neck-Soft Tissue Infection MRI Orbits/Face/Neck without 70543 Tumor/Mass/Cancer/Mets and with Contrast Vocal Cord Paralysis 6/14 Scheduling: 717.291.1016 or 888.MRI.1377 Fax: 717.509.8642 ● Web Site: www.MRIGroup.com Contrast vs. No Contrast Reference Sheet – Spine Body Part Reason for Exam Procedure to Pre-Cert CPT Code Spine: Cervical Degenerative Disease MRI Cervical Spine without Contrast 72141 Disc Herniation Extremity Pain/Weakness Neck Pain Radiculopathy Trauma Spine: -

Torticollis Is a Clinical Diagnosis Based on Head Tilt in Association with a Rotatory Deviation of the Cranium

24. Define type of torticollis? Torticollis is a clinical diagnosis based on head tilt in association with a rotatory deviation of the cranium. Congenital muscular torticollis is the most common type of torticollis. It presents in the newborn period. Its cause is unknown, but it has been hypothesized to arise from compression of the soft tissues of the neck during delivery, resulting in a compartment syndrome. Radiographs of the cervical spine should be obtained to rule out congenital vertebral anomalies. Clinical examination reveals spasm of the sternocleidomastoid muscle on the same side as the tilt causing the typical posture of head tilt toward the tightened muscle and chin rotation to the opposite side. Initial treatment is stretching and is successful in up to 90% of patients during the first year of life. Surgery is considered for persistent deformity after 1 year of age. Common problems noted in patients with congenital muscular torticollis include congenital hip dysplasia and plagiocephaly (facial asymmetry). Source: Spine Secret Plus, 2nd ed. page 256. 25. What clinical problems result from basilar impression? Patients present with a short neck, painful cervical motion, and asymmetric of the skull and face. Additional clinical problems include nuchal pain, vertigo, long tract signs with associated cerebellar ataxia, and lower cranial nerve involvement resulting in dysarthria and dysphagia Source: Spine Secret Plus, 2nd ed. page 258 26. What is Steel’s Rule of Third? Steel noted that the area of the spinal canal at the C1 leve in a normal person could be divided into equal thirds with one third occupied by the odontoid process, one third by the spinal cord, and one third as empty space. -

Sciatica and Chronic Pain

Sciatica and Chronic Pain Past, Present and Future Robert W. Baloh 123 Sciatica and Chronic Pain Robert W. Baloh Sciatica and Chronic Pain Past, Present and Future Robert W. Baloh, MD Department of Neurology University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA, USA ISBN 978-3-319-93903-2 ISBN 978-3-319-93904-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93904-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018952076 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2019 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. -

Cervical Neck Pain Or Cervical Radiculopathy

Revised 2018 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Cervical Neck Pain or Cervical Radiculopathy Variant 1: New or increasing nontraumatic cervical or neck pain. No “red flags.” Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level Radiography cervical spine Usually Appropriate ☢☢ MRI cervical spine without IV contrast May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) O CT cervical spine without IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT cervical spine with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ MRI cervical spine without and with IV Usually Not Appropriate contrast O CT cervical spine without and with IV Usually Not Appropriate contrast ☢☢☢ CT myelography cervical spine Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ CTA neck with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ Discography cervical spine Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢ Facet injection/medial branch block cervical Usually Not Appropriate spine ☢☢ MRA neck with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRA neck without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O MRI cervical spine with IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate O Bone scan whole body with SPECT or Usually Not Appropriate SPECT/CT neck ☢☢☢ X-ray myelography cervical spine Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Cervical Neck Pain or Cervical Radiculopathy Variant 2: New or increasing nontraumatic cervical radiculopathy. No “red flags.” Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level MRI cervical spine without IV contrast Usually Appropriate O CT cervical spine without IV contrast -

Can Eyes Cause Neck Pain? International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 23 (10)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link Citation: Hood, Wendy and Hood, Martin (2016) Can eyes cause neck pain? International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 23 (10). pp. 499-504. ISSN 1741-1645 Published by: Mark Allen Publishing URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2016.23.10.499 <http://dx.doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2016.23.10.499> This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/28627/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription may be required.) Sensory Integration: Can eyes cause neck pain? Abstract This article is an analysis of literature relating to ocular-motor imbalance and the potential postural consequences. -

Acute Calcific Discitis with Intravertebral Disc Herniation in the Dorsolumbar Spine

Published online: 2021-08-02 MUSCULOSKELETAL Case report: Acute calcific discitis with intravertebral disc herniation in the dorsolumbar spine Puneet Mittal, Kavita Saggar, Parambir Sandhu, Kamini Gupta Department of Radiodiagnosis, Dayanand Medical College & Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab, India Correspondence: Dr. Puneet Mittal, Department of Radiodiagnosis, Dayanand Medical College & Hospital, Tagore Nagar, Civil Lines, Ludhiana, Punjab - 141 001, India. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Acute calcific discitis is a rare but well-known condition of unknown etiology. In symptomatic cases, the most common site is the cervical spine. We describe the CT scan and MRI findings in a symptomatic patient, with a lesion in the dorsolumbar spine. Key words: Acute; calcific; discitis; dorsolumbar; MR Introduction Acute calcifc discitis is a rare condition. When symptomatic, it can be mistaken for infection.[1] Most of the symptomatic cases present in the cervical spine.[1-3] We present the CT scan and MRI findings in a patient who had involvement of the dorsolumbar spine, with associated intravertebral disc herniation. Case Report A 10-year-old boy presented with a 2-week history of pain in the lower back following a yoga session in school. The pain had gradually worsened over the last 5 days. The patient was afebrile. The total white blood cell (WBC) count was normal. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was raised (52 mm/h). The Mantoux test was negative. A radiograph obtained elsewhere and repeated a day after the MRI [Figure 1], showed calcification of the D12-L1 intervertebral disc. MRI showed hypointense signal in the D12-L1 intervertebral disc on T1W [Figure 2A] and T2W [Figure 2B and C] images. -

Cervical Spondylodiscitis in an Infant with Torticollis

Cervical Spondylodiscitis in IMAGES IN CLINICAL an Infant with Torticollis RADIOLOGY BRECHT VAN BERKEL KRISTIN SUETENS LUC BREYSEM *Author affiliations can be found in the back matter of this article ABSTRACT CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Brecht Van Berkel Teaching point: Narrowing of the intervertebral space and destruction of the adjacent UZ Leuven, BE vertebral end plates on conventional radiography or CT should raise suspicion for brecht.vanberkel@student. spondylodiscitis in symptomatic infants. kuleuven.be KEYWORDS: Spondylodiscitis; MRI; pediatric; torticollis; cervical; CT TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Van Berkel B, Suetens K, Breysem L. Cervical Spondylodiscitis in an Infant with Torticollis. Journal of the Belgian Society of Radiology. 2021; 105(1): 35, 1–4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/ jbsr.2454 Van Berkel et al. Journal of the Belgian Society of Radiology DOI: 10.5334/jbsr.2454 2 CASE REPORT disc space and loss of height of vertebral bodies C3 and C4 and irregular alignment of the end plates. On An eight-month-old infant presented at the emergency the sagittal T1-weighted Short-tau inversion-recovery department with a history of torticollis for six weeks. (STIR) images, the hyperintense signal in the vertebral Blood results showed no elevated inflammatory bodies of C3 and C4, as well as in the surrounding tissues parameters. Vertical lateral X-ray of the cervical spine (arrowheads) were compatible with a widespread area demonstrated a kyphotic angulation at the level of C3– of bone and soft tissue oedema (Figure 2). There were C4, narrowing of the intervertebral disc space, irregular no diffusion-restricted areas and no accompanying fluid end plates, and loss of height of the vertebral body of collections. -

CASE REPORT Cervical Spondylolysis

Acta Orthop. Belg., 2006, 72, 511-516 CASE REPORT Cervical spondylolysis : A case report Seddik OUESLATI, Khalil ZAOUIA, Mouna CHELLI From the M. Matri Hospital, Ariana, Tunisia Cervical spondylolysis is defined as a corticated cleft a relatively innocuous condition, thus preventing between the superior and inferior articular facets of inappropriate treatment and unnecessary surgery. the articular pillar, the cervical equivalent of the pars We present a case of this anomaly as imaged interarticularis in the lumbar spine. Of primary with plain radiography, computed tomography and importance is its recognition to avoid confusion with MRI. Differential diagnosis and a brief review of more clinically significant abnormalities such as the literature are discussed. fracture or dislocation. This case report describes bilateral spondylolysis and associated dysplasia of C5 in a 31-year-old female. CASE REPORT We describe the radiographic presentation of this anomaly, stressing the importance of computed A 31-year-old woman was referred by her gen- tomography for correct diagnosis. eral practioner to our hospital, with neck and right A review of the literature on this interesting abnor- shoulder pain. This had started 7 years previously mality and a complete differential diagnosis are pre- without any identifiable trauma or other precipitat- sented. ing event. She was then treated conservatively with analgesics. Three months prior to her consultation, Keywords : cervical spine ; spondylolysis ; spondylolis- her neck pain worsened, without any neurological thesis ; radiography ; computed tomography ; magnetic deficit. On physical examination weakness of resonance imaging. abduction of the right shoulder was noted. Palpation of her neck revealed mild tenderness over the mid-cervical spine with painful limitation of INTRODUCTION Spondylolysis with or without spondylolisthesis is a rare condition in the cervical spine, charac- terised by the presence of a corticated cleft between ■ Seddik Oueslati, MD, Registrar. -

Pattern of Premature Degenerative Changes of the Cervical Spine in Patients with Spasmodic Torticollis and the Impact on The

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68:465–471 465 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.68.4.465 on 1 April 2000. Downloaded from Pattern of premature degenerative changes of the cervical spine in patients with spasmodic torticollis and the impact on the outcome of selective peripheral denervation S J Chawda, A Münchau, D Johnson, K Bhatia, N P Quinn, J Stevens, A J Lees, J D Palmer Abstract modic torticollis with botulinum toxin Objectives—To characterise the pattern of seems to have a protective eVect. Patients and risk factors for degenerative changes with spasmodic torticollis and restricted of the cervical spine in patients with spas- head mobility who do not adequately modic torticollis and to assess whether respond to treatment should undergo these changes aVect outcome after selec- imaging of the upper cervical spine. tive peripheral denervation. Patients with imaging evidence of moder- Methods—Preoperative CT of the upper ate or severe degenerative changes seem cervical spine of 34 patients with spas- to respond poorly to selective peripheral modic torticollis referred for surgery were denervation. reviewed by two radiologists blinded to the (J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68:465–471) clinical findings. Degenerative changes were assessed for each joint separately Keywords: osteoarthritis; spasmodic torticollis; com- and rated as absent, minimal, moderate, puted tomography; selective peripheral denervation or severe. Patients were clinically assessed before surgery and 3 months postopera- Idiopathic spasmodic torticollis is the most tively by an independent examiner using common form of adult onset focal dystonia.1 It standardised clinical rating scales. For comparison of means a t test was carried is characterised by repetitive or sustained con- tractions of neck muscles that lead to an out. -

Cervical Radiculopathy Clinical Guidelines for Medical Necessity Review

Cervical Radiculopathy Clinical Guidelines for Medical Necessity Review Version: 3.0 Effective Date: November 13, 2020 Cervical Radiculopathy (v3.0) © 2020 Cohere Health, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 2 Important Notices Notices & Disclaimers: GUIDELINES SOLELY FOR COHERE’S USE IN PERFORMING MEDICAL NECESSITY REVIEWS AND ARE NOT INTENDED TO INFORM OR ALTER CLINICAL DECISION MAKING OF END USERS. Cohere Health, Inc. (“Cohere”) has published these clinical guidelines to determine medical necessity of services (the “Guidelines”) for informational purposes only, and solely for use by Cohere’s authorized “End Users”. These Guidelines (and any attachments or linked third party content) are not intended to be a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment directed by an appropriately licensed healthcare professional. These Guidelines are not in any way intended to support clinical decision making of any kind; their sole purpose and intended use is to summarize certain criteria Cohere may use when reviewing the medical necessity of any service requests submitted to Cohere by End Users. Always seek the advice of a qualified healthcare professional regarding any medical questions, treatment decisions, or other clinical guidance. The Guidelines, including any attachments or linked content, are subject to change at any time without notice. ©2020 Cohere Health, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Other Notices: CPT copyright 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. -

Adolescent Idiopathic Torticollis: Morphological Vertebral Changes of the Spinal Canal and the Spinal Cord Position: a Case Report

ISSN: 2469-5777 Carbonell and Ruiz. Trauma Cases Rev 2017, 3:056 DOI: 10.23937/2469-5777/1510056 Volume 3 | Issue 2 Trauma Cases and Reviews Open Access CASE REPORT Adolescent Idiopathic Torticollis: Morphological Vertebral Chang- es of the Spinal Canal and the Spinal Cord Position: A Case Report Pedro Gutiérrez Carbonell* and Ruiz Miñana E Check for Department of Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology, General University Alicante Hospital, Spain updates *Corresponding author: Pedro Gutiérrez Carbonell, Department of Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology, General Uni- versity Alicante Hospital, Paraje Ledua E-25, 03660-Novelda, Spain, Tel: 00-34-606-468-139, Fax: 00-34-965-242-454, E-mail: [email protected] (Sandifer Syndrome), traumatic or oropharyngeal inflam- Abstract mation (Grisel’s Syndrome), anomalies of the brain stem Cervical spinal canal deformities can be caused by muscu- and cervical spine (syringomyelia, diastematomyelia and lar deforming forces, as in the case of a 10-year-old male with inveterate left torticollis. Atlas and axis bone deformi- Arnold-Chiari malformation) or tumors of the posterior ties were observed, including subluxation of the odontoid cranial fossa (astrocytoma and ependymoma) [1-5]. After apophysis, hypertrophy of the anterior arch of the atlas, hy- this wide differential diagnosis was made, orthopedic and poplasia of the posterior arches of atlas, and deformation occasionally surgical treatment of torticollis with muscular of the spinal canal accompanied by an eccentric position of the spinal cord. After tenotomy of Sternocleidomastoid etiology is performed, preferably, within the first year of Muscle (SCM) and 5-years of follow-up, the deformities life, because after this age facial deformities are irrevers- were unchanged. -

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Clinical Guidelines for Medical Necessity Review

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Clinical Guidelines for Medical Necessity Review Version: 4.0 Effective Date: November 13, 2020 Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (v4.0) © 2020 Cohere Health, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Important Notices Notices & Disclaimers: GUIDELINES SOLELY FOR COHERE’S USE IN PERFORMING MEDICAL NECESSITY REVIEWS AND ARE NOT INTENDED TO INFORM OR ALTER CLINICAL DECISION MAKING OF END USERS. Cohere Health, Inc. (“Cohere”) has published these clinical guidelines to determine medical necessity of services (the “Guidelines”) for informational purposes only, and solely for use by Cohere’s authorized “End Users”. These Guidelines (and any attachments or linked third party content) are not intended to be a substitute for medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment directed by an appropriately licensed healthcare professional. These Guidelines are not in any way intended to support clinical decision making of any kind; their sole purpose and intended use is to summarize certain criteria Cohere may use when reviewing the medical necessity of any service requests submitted to Cohere by End Users. Always seek the advice of a qualified healthcare professional regarding any medical questions, treatment decisions, or other clinical guidance. The Guidelines, including any attachments or linked content, are subject to change at any time without notice. ©2020 Cohere Health, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Other Notices: CPT copyright 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. CPT is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. Guideline Information: Specialty Area: Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (M00-M99) CarePath Group: Spine CarePath Name: Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (M48) Physician author: Mandy Armitage, MD (Sports Medicine) Peer reviewed by: Adrian Thomas, MD (Orthopedic Spine Surgeon) Literature review current through: June 22, 2020 Document last updated: November 13, 2020 Type: [X] Adult (18+ yo) | [_] Pediatric (0-17yo) Page 2 of 57 Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (v4.0) © 2020 Cohere Health, Inc.