Nations and National Identities in the Medieval World: an Apologia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wild’ Evaluation Between 6 and 9Years of Age

FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:05 PM Residential&Commercial Sales and Rentals tvspotlight Vadala Real Proudly Serving Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Cape Ann Since 1975 Estate • For the week of July 11 - 17, 2015 • 1 x 3” Massachusetts Certified Appraisers 978-281-1111 VadalaRealEstate.com 9-DDr. OsmanBabsonRd. Into the Gloucester,MA PEDIATRIC ORTHODONTICS Pediatric Orthodontics.Orthodontic care formanychildren can be made easier if the patient starts fortheir first orthodontic ‘Wild’ evaluation between 6 and 9years of age. Some complicated skeletal and dental problems can be treated much more efficiently if treated early. Early dental intervention including dental sealants,topical fluoride application, and minor restorativetreatment is much more beneficial to patients in the 2-6age level. Parents: Please makesure your child gets to the dentist at an early age (1-2 years of age) and makesure an orthodontic evaluation is done before age 9. Bear Grylls hosts Complimentarysecond opinion foryour “Running Wild with child: CallDr.our officeJ.H.978-283-9020 Ahlin Most Bear Grylls” insurance plans 1accepted. x 4” CREATING HAPPINESS ONE SMILE AT ATIME •Dental Bleaching included forall orthodontic & cosmetic dental patients. •100% reduction in all orthodontic fees for families with aparent serving in acombat zone. Call Jane: 978-283-9020 foracomplimentaryorthodontic consultation or 2nd opinion J.H. Ahlin, DDS •One EssexAvenue Intersection of Routes 127 and 133 Gloucester,MA01930 www.gloucesterorthodontics.com Let ABCkeep you safe at home this Summer Home Healthcare® ABC Home Healthland Profess2 x 3"ionals Local family-owned home care agency specializing in elderly and chronic care 978-281-1001 www.abchhp.com FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:06 PM 2 • Gloucester Daily Times • July 11 - 17, 2015 Adventure awaits Eight celebrities join Bear Grylls for the adventure of a lifetime By Jacqueline Spendlove TV Media f you’ve ever been camping, you know there’s more to the Ifun of it than getting out of the city and spending a few days surrounded by nature. -

Drew Hayden Taylor, Native Canadian Playwright in His Times

BRIDGING THE GAP: DREW HAYDEN TAYLOR, NATIVE CANADIAN PLAYWRIGHT IN HIS TIMES Dale J. Young A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2005 Committee: Dr. Ronald E. Shields, Advisor Dr. Lynda Dixon Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Jonathan Chambers Bradford Clark © 2005 Dale Joseph Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Ronald E. Shields, Advisor In his relatively short career, Drew Hayden Taylor has amassed a significant level of popular and critical success, becoming the most widely produced Native playwright in the world. Despite nearly twenty years of successful works for the theatre, little extended academic discussion has emerged to contextualize Taylor’s work and career. This dissertation addresses this gap by focusing on Drew Hayden Taylor as a writer whose theatrical work strives to bridge the distance between Natives and Non-Natives. Taylor does so in part by humorously demystifying the perceptions of Native people. Taylor’s approaches to humor and demystification reflect his own approaches to cultural identity and his expressions of that identity. Initially this dissertation will focus briefly upon historical elements which served to silence Native peoples while initiating and enforcing the gap of misunderstanding between Natives and non-Natives. Following this discussion, this dissertation examines significant moments which have shaped the re-emergence of the Native voice and encouraged the formation of the Contemporary Native Theatre in Canada. Finally, this dissertation will analyze Taylor’s methodology of humorous demystification of Native peoples and stories on the stage. -

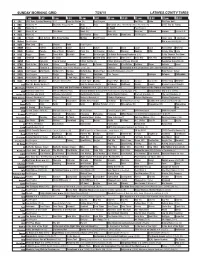

Sunday Morning Grid 7/26/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 7/26/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Golf Res. Faldo PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Volleyball 2015 FIVB World Grand Prix, Final. (N) 2015 Tour de France 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Outback Explore Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Rio ››› (2011) (G) 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Contac Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap (TVG) Celtic Thunder The Show 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Cinderella Man ››› 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Tras la Verdad Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Hour of In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Hungria 2015. -

A Feminist-Foucauldian Approach to Sexual Violence and Survival

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2015 Surviving History of Sexuality: A Feminist-Foucauldian Approach to Sexual Violence and Survival Merritt Rehn-Debraal Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rehn-Debraal, Merritt, "Surviving History of Sexuality: A Feminist-Foucauldian Approach to Sexual Violence and Survival" (2015). Dissertations. 1967. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1967 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2015 Merritt Rehn-Debraal LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO SURVIVING HISTORY OF SEXUALITY: A FEMINIST-FOUCAULDIAN APPROACH TO SEXUAL VIOLENCE AND SURVIVAL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN PHILOSOPHY BY MERRITT REHN-DEBRAAL CHICAGO, IL DECEMBER 2015 Copyright by Merritt Rehn-DeBraal, 2015 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For his breadth of knowledge, insights, and careful readings I am grateful to my dissertation director, Andrew Cutrofello. Many thanks also to my other readers: Jacqueline Scott, who has undoubtedly helped me to become a better writer and philosopher; and Hanne Jacobs, whose enthusiasm renews my excitement in my own research. I am additionally appreciative of Hugh Miller and Jennifer Parks for raising questions at my proposal defense that helped to make my final project stronger. -

12-05-2008.Pdf2013-02-12 15:4711.4 MB

ISIE: 2 OICES AAIC SEACOAS OIAYS l lvr fr G O AGE A IAY, ECEME , 2008 8A, A8A O OU rntdEWS I Et Kntn I Extr I Grnlnd I ptn I ptn h I ptn ll vl. 4 I . 4 24 Knntn I fld I rth ptn I I h I Sbr I Sth ptn I Strth SEACOAS OIAY SECIO Cnnll Cntn C j. I .Atlnt. I 0 El Strt, Slbr, MA 02 I (60 26 I EE • AKE OE SbK Shl rt Offr n thbt In th rr I br Shl r Offr h fnrprnt ntr hl prn Chld Sft I Kt. Offr h, h ptrd th Sbr tt Offr hn Mn, l dtrbtd lr t t th r SES Sft . nd th lAr nd t r bt th SO tpl hl d n th nth f 2 n A6A nd 2A22A. — Atlnt ht State reports first flu case I EMO Cnt dlt. W n t nl AAIC EWS SA WIE h n ttr f t bfr th "WE KEW nflnz h ht th frd lt b th fl rrvd hr n I WAS OY • Grnt Stt. bl lth brt phr," d S Ardn t th r. In n th ff Cnr hl A MAE O prtnt f lth nd l nnnnt, IMS rnp. n Srv (S, ntd tht th tn fr Cd b vr, IME." OOK WOS EE — St f fl l Arthr th frt f nflnz th frt f th fl nflnz hhl n (ptrd h p n th St drn th Chrt n phr fr fr 2008 rlr thn lt t lln, prdn n. -

Spirit Week! the Science Behind Happiness a Look at “Soaring Valor”

The Knight Magazine November 2017 1 NOVEMBER 2017 A DISCUSSION ABOUT GUN OWNERSHIP THE KNIGHT MAGAZINE Spirit Week! The Science Behind Happiness A Look At “Soaring Valor” PLUS: Student Spotlight on Photography Girls Golf & Boys Varsity Water Polo Letter from the Editors Hello, fellow students. We want to thank you for such a positive reception to our first issue of the Knight Magazine this year. We have been working non-stop since the previous magazine was published, and hope that you enjoy this one as much as its predecessor. In this issue we tackle issues like gun ownership, the ever-threatening opioid epidemic, and the increase of American troops in Afghanistan. On the lighter side, we hope you enjoy the Spirit Week pictorial put together by the new Publications Club, as well as some Thanksgiving recipes. It is no secret that a lot has happened since our last update. Between the tragic massacre in Las Vegas, the many hurricanes that have pummeled American shores, and a Dodgers World Series loss in Game 7, just to name a few events. As your Editors-in-Chief, we continue to try to promote healthy debate within our student body. For stories published more frequently, visit our school blog at ndhsmedia.com. If you want to be a part of this Notre Dame Publications mission, please see Mrs. Landinguin or Mrs. Moulton in room 40. Your Editors, Bridget Gehan ‘18 and Maria Thomas ‘18 THE KNIGHT MAGAZINE BRIDGET GEHAN ‘18 CO-EDITOR-IN-CHIEF MARIA THOMAS ‘18 CO-EDITOR-IN-CHIEF MARIA GUINNIP ‘20 Staff Writer BLATHNAID HEANEY ‘19 Staff Writer ASHWIN MILLS ‘18 Staff Writer SARAH O’BRIEN ‘19 Staff Writer DOMINIC PALOSZ ‘18 Staff Writer DANI POSIN ‘18 Staff Writer ALLYSON ROCHE ‘19 Staff Writer EVIN SANTANA ‘19 Staff Writer CHRISTINA SHIRLEY ‘18 Staff Writer MRS. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

Constructed Situations: a New History of the Situationist International

ConstruCted situations Stracey T02909 00 pre 1 02/09/2014 11:39 Marxism and Culture Series Editors: Professor Esther Leslie, Birkbeck, University of London Professor Michael Wayne, Brunel University Red Planets: Marxism and Science Fiction Edited by Mark Bould and China Miéville Marxism and the History of Art: From William Morris to the New Left Edited by Andrew Hemingway Magical Marxism: Subversive Politics and the Imagination Andy Merrifield Philosophizing the Everyday: The Philosophy of Praxis and the Fate of Cultural Studies John Roberts Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture Gregory Sholette Fredric Jameson: The Project of Dialectical Criticism Robert T. Tally Jr. Marxism and Media Studies: Key Concepts and Contemporary Trends Mike Wayne Stracey T02909 00 pre 2 02/09/2014 11:39 ConstruCted situations A New History of the Situationist International Frances Stracey Stracey T02909 00 pre 3 02/09/2014 11:39 For Peanut First published 2014 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © the Estate of Frances Stracey 2014 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3527 8 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3526 1 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7837 1223 6 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1225 0 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1224 3 EPUB eBook Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. -

DVD List As of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret

A LIST OF THE NEWEST DVDS IS LOCATED ON THE WALL NEXT TO THE DVD SHELVES DVD list as of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret Garden, The Witches, The Neverending Story, 5 Children & It) 5 Days of War 5th Quarter, The $5 A Day 8 Mile 9 10 Minute Solution-Quick Tummy Toners 10 Minute Solution-Dance off Fat Fast 10 Minute Solution-Hot Body Boot Camp 12 Men of Christmas 12 Rounds 13 Ghosts 15 Minutes 16 Blocks 17 Again 21 21 Jumpstreet (2012) 24-Season One 25 th Anniversary Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Concerts 28 Weeks Later 30 Day Shred 30 Minutes or Less 30 Years of National Geographic Specials 40-Year-Old-Virgin, The 50/50 50 First Dates 65 Energy Blasts 13 going on 30 27 Dresses 88 Minutes 102 Minutes That Changed America 127 Hours 300 3:10 to Yuma 500 Days of Summer 9/11 Commission Report 1408 2008 Beijing Opening Ceremony 2012 2016 Obama’s America A-Team, The ABCs- Little Steps Abandoned Abandoned, The Abduction About A Boy Accepted Accidental Husband, the Across the Universe Act of Will Adaptation Adjustment Bureau, The Adventures of Sharkboy & Lavagirl in 3-D Adventures of Teddy Ruxpin-Vol 1 Adventures of TinTin, The Adventureland Aeonflux After.Life Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Murder of Roger Ackroyd Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Sad Cypress Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Hollow Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Five Little Pigs Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Lord Edgeware Dies Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Evil Under the Sun Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Murder in Mespotamia Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Death on the Nile Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Taken at -

Rehtinking Resistance: Race, Gender, and Place in the Fictive and Real Geographies of the American West

REHTINKING RESISTANCE: RACE, GENDER, AND PLACE IN THE FICTIVE AND REAL GEOGRAPHIES OF THE AMERICAN WEST by TRACEY DANIELS LERBERG DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington May 2016 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Stacy Alaimo, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Christopher Morris Kenneth Roemer Cedrick May, Texas Christian University Abstract Rethinking Resistance: Race, Gender, and Place in the Fictive and Real Geographies of the American West by Tracey Daniels Lerberg, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Stacy Alaimo This project traces the history of the American West and its inhabitants through its literary, cinematic and cultural landscape, exploring the importance of public and private narratives of resistance, in their many iterations, to the perceived singular trajectory of white masculine progress in the American west. The project takes up the calls by feminist and minority scholars to broaden the literary history of the American West and to unsettle the narrative of conquest that has been taken up to enact a particular kind of imaginary perversely sustained across time and place. That the western heroic vision resonates today is perhaps no significant revelation; however, what is surprising is that their forward echoes pulsate in myriad directions, cascading over the stories of alternative voices, that seem always on the verge of slipping away from our collective memories, of ii being conquered again and again, of vanishing. But a considerable amount of recovery work in the past few decades has been aimed at revising the ritualized absences in the North American West to show that women, Native Americans, African Americans, Mexican Americans and other others were never absent from this particular (his)story. -

Holocaust Memory for the Millennium

HHoollooccaauusstt MMeemmoorryy ffoorr tthhee MMiilllleennnniiuumm LLaarriissssaa FFaayyee AAllllwwoorrkk Royal Holloway, University of London Submission for the Examination of PhD History 1 I Larissa Allwork, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: L.F. Allwork Date: 15/09/2011 2 Abstract Holocaust Memory for the Millennium fills a significant gap in existing Anglophone case studies on the political, institutional and social construction of the collective memory of the Holocaust since 1945 by critically analyzing the causes, consequences and ‘cosmopolitan’ intellectual and institutional context for understanding the Stockholm International Forum on Holocaust Education, Remembrance and Research (26 th January-28 th January 2000). This conference was a global event, with ambassadors from 46 nations present and attempted to mark a defining moment in the inter-cultural construction of the political and institutional memory of the Holocaust in the United States of America, Western Europe, Eastern Europe and Israel. This analysis is based on primary documentation from the London (1997) and Washington (1998) restitution conferences; Task Force for International Cooperation on Holocaust Education, Remembrance and Research primary sources; speeches and presentations made at the Stockholm International Forum 2000; oral history interviews with a cross-section of British delegates to the conference; contemporary press reports, -

Presentations

PRESENTATIONS Canoecopia Presentations for 2018 Places to go, things to do, new ways to do it. We’ve got it all and then some. the right size are all available to you as a paddle Four Rivers to the Labrador Sea Christopher Amidon maker, not to mention choosing the wood you Sun 11:30a, Superior Paddling Isle Royale National Park want in your paddle. Stop by and view the demo Sat 2:30p, Superior Jim set off on a 33-day canoe trip from Sun 12:30p, Superior paddles and materials that wavetrainSUP uses Shefferville, Quebec to Hopedale, Labrador via Isle Royale National Park offers unique to build handmade wood paddles for both canoe the Du Pas, George, Adlatok and an unnamed opportunities for paddling in and around and SUP. river. With three height-of-land crossings, a wilderness island in Lake Superior. The significant up-river travel on the George, raging challenges facing paddlers are many, from the whitewater runs on the Adlatok, and two trail- logistics of transporting equipment, to the New less, two-day portages, this is a tough route by unpredictable, cold waters of Lake Superior. any standards. And that’s not even considering Join Ranger Chris Amidon to explore the the blackflies, bear trouble, bad weather and paddling options and challenges of Isle Royale lack of food that Jim and his group of four dealt National Park. with on the journey. Lessons from the Trail abc Sat 2:30p, Quetico Greg Anderson They say good decisions come from experience, The Wild Coast: and experience comes from bad decisions.