The Reception of Danish Science Fiction in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lightspeed Magazine, Issue 66 (November 2015)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 66, November 2015 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial, November 2015 SCIENCE FICTION Here is My Thinking on a Situation That Affects Us All Rahul Kanakia The Pipes of Pan Brian Stableford Rock, Paper, Scissors, Love, Death Caroline M. Yoachim The Light Brigade Kameron Hurley FANTASY The Black Fairy’s Curse Karen Joy Fowler When We Were Giants Helena Bell Printable Toh EnJoe (translated by David Boyd) The Plausibility of Dragons Kenneth Schneyer NOVELLA The Least Trumps Elizabeth Hand NOVEL EXCERPTS Chimera Mira Grant NONFICTION Artist Showcase: John Brosio Henry Lien Book Reviews Sunil Patel Interview: Ernest Cline The Geek’s Guide to the Galaxy AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS Rahul Kanakia Karen Joy Fowler Brian Stableford Helena Bell Caroline M. Yoachim Toh EnJoe Kameron Hurley Kenneth Schneyer Elizabeth Hand MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Upcoming Events Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks About the Lightspeed Team Also Edited by John Joseph Adams © 2015 Lightspeed Magazine Cover by John Brosio www.lightspeedmagazine.com Editorial, November 2015 John Joseph Adams | 712 words Welcome to issue sixty-six of Lightspeed! Back in August, it was announced that both Lightspeed and our Women Destroy Science Fiction! special issue specifically had been nominated for the British Fantasy Award. (Lightspeed was nominated in the Periodicals category, while WDSF was nominated in the Anthology category.) The awards were presented October 25 at FantasyCon 2015 in Nottingham, UK, and, alas, Lightspeed did not win in the Periodicals category. But WDSF did win for Best Anthology! Huge congrats to Christie Yant and the rest of the WDSF team, and thanks to everyone who voted for, supported, or helped create WDSF! You can find the full list of winners at britishfantasysociety.org. -

Science Fiction Drama: Promoting Posthumanism Hend Khalil the British University in Egypt

Hend Khalil Science Fiction Drama: Promoting Posthumanism Hend Khalil The British University in Egypt The current hype of artificial intelligence or non-humans manifested via Sophia, the social humanoid robot which has been developed by the founder of Hanson Robotics, Dr. David Hanson, in 2015 depicts the apprehension voiced out by some scientists as regards to artificial intelligence (AI) taking over the world through automating workforce and annihilating human race. Strikingly enough, Sophia communicates with humans, displays sixty different emotions, and travels throughout the whole world to participate in scientific forums and conferences. Moreover, she has been granted the Saudi nationality and is proud “to be the first robot in the world to be granted a citizenship.” (Sorkin) Interviewed in the Future Investment Initiative in Riyad, Sophia has declared that her “aim is to help humans live a better life through artificial intelligence.” (Sorkin) The imaginary robots portrayed in science fiction works of art have become a reality! Nevertheless, the fear of artificial intelligence still looms over. Science fiction writers thought of and wrote about inventions long before they were invented. “It was science-fiction writers whose imagination put submarines, rockets, atomic weaponry, space ships, and computers to work before they had even been invented” (Willingham 4). They imagined new possibilities for humanity transgressing past and present experience (Willingham 2). In spite of the fact that science fiction writers imagined the potential advances of science and technology, they feared the consequences of the new rattling machines and other technological inventions. Artificial intelligence is basically one of the most prominent themes tackled through science fiction. -

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 10-1-1996 SFRA ewN sletter 225 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 225 " (1996). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 164. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/164 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (i j ,'s' Review= Issue #225, September/October 1996 IN THIS ISSUE: SFRA INTERNAL AFFAIRS: Proposed SFRA Logo.......................................................... 5 President's Message (Sanders) ......................................... 5 Officer Elections/Candidate Statements ......................... 6 Membership Directory Updates ..................................... 10 SFRA Members & Friends ............................................... 10 Letters (Le Guin, Brigg) ................................................... 11 Editorial (Sisson) ............................................................. 13 NEWS AND INFORMATION ......................................... -

Bibiiography

.142; Aldiss, Brian W., and David Wingrove. Trillion Year Spree: The History of Science Fiction. New York: Atheneum, 1986. A revision of Aldiss’s earlier Billion Year Spree, this is a literate overall history of science fiction by one of England’s leading authors in the genre. Ashley, Mike. The Story of the Science Fiction Magazines. Volume I: The Time Machines: The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the Beginning to 1950. Volume II: Transformations: The Story of the Science Fiction Magazines from 1950 to 1970. Volume III: Gateways to Forever: The Story of the Science Fiction Magazines from 1970 to 1980. Liverpool, England: Liverpool University Press, 2000–2007. These three volumes, from one of Britain’s leading historians of science fiction, cover the entire history of magazine science fiction over more than five decades, discussing the role of various editors and writers, as well as the major stories of each era. Attebery, Brian W. Decoding Gender in Science Fiction. New York: Routledge, 2002. An astute examination of gender and feminist themes in science fiction by one of the leading scholars of science fiction and fantasy. Bleiler, Everett. Science-Fiction: The Early Years. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1991. A comprehensive summary and analysis of nearly 2,000 individual stories that appeared in science fiction pulp magazines between 1926 and 1936 and an invaluable guide to the early pulp era. Bould, Mark, Andrew M. Butler, Adam Roberts, and Sherryl Vint, eds. The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction. London and New York: Routledge, 2009. A collection of 56 essays on various aspects of science fiction by leading writers and critics in the field. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter free, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. The Commonplace Within the Fantastic: Terry Bisson's Art in the Diversified Science Fiction Genre Jane Powell Campbell A dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Arts May ]998 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

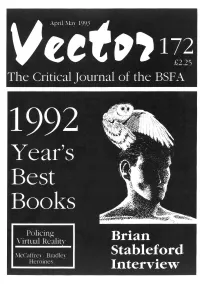

Brian Stableford Interview

Policing Yirtual Rca!tt,· Brian Stableford -.\lcC1ll1c1 81.1dlc1 lle1omcs Interview 2 Vector Contents Nuts & Bolts 3 Front Line Dispatches - Letters I owe you all an apology - your mailing is 6 Brian Stableford late and it's all my fault. I'm sure you don't need Interviewed by Catie Cary to hear excuses, but you 're getting them 11 Policing Virtual Reality by Ian Sales anyway. Since the beginning of February, since 13 Reviewers'Poll -1992 the morning I delivered the last issue of Vector 16 Only A Girl by Carol Ann Green in fact, I have been working in Norwich, while 18 First Impressions continuing to try to produce Vector from my Reviews edited by Catie Cary home in Guildford. This has created all sorts of 26 Barbed Wire Kisses - Magazine difficulties, and Vector has suffered less than Reviews edited by Maureen Speller many other areas of my life. I've had to be fairly 30 Paperback Graffiti ruthless in setting my priorities to get here at all. edited by Stephen Payne Furthermore, I owe an apology to all the people who have written to me over the last few Cover Artwork by Claire Willoughby months; some to offer help, and to whom I have not yet replied. Your interest and support has Editor & Hardback Reviews been much appreciated, believe me, and you Catie Cary 224 Southway, Park Barn, should be hearing from me "real soon now" . Guildford, Surrey, GU2 6DN The less forgiving of you will now be asking Phone: 0483 502349 whether this means that you have in your hands a second class scrambled magazine. -

The Reception of Danish Science Fiction in the United States Kristine J

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Libraries Research Publications 6-13-2006 The Reception of Danish Science Fiction in the United States Kristine J. Anderson Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_research Anderson, Kristine J., "The Reception of Danish Science Fiction in the United States" (2006). Libraries Research Publications. Paper 71. http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_research/71 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. The Reception of Danish Science Fiction in the United States by Kristine J. Anderson Science fiction is a distinctly American genre. Although scholars have traced its origins back as far as the Latin writer Lucian of Samosata, 1 it was Hugo Gernsback, a publisher of pulp magazines in the United States, who first gave the genre its name in the June 1929 issue of Wonder Stories . Gernsback had been serializing the scientific romances of such writers as Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, emphasizing their treatment of technology and putting them forth as models for other budding writers to imitate. The magazines that Gernsback initiated became very popular, spawning more from other publishers. Groups of aficionados sprang up around them, provided with a forum by Ge rnsback’s letters columns, where they happily exchanged opinions and found addresses with which to contact one another outside the magazine. In this way Gernsback also gave birth to science fiction fandom, which then went on to produce successful authors from its own ranks to write for all the science fiction magazines then pouring off the presses. -

'Determined to Be Weird': British Weird Fiction Before Weird Tales

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Birkbeck, University of London ‘Determined to be Weird’: British Weird Fiction before Weird Tales James Fabian Machin Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2016 1 Declaration I, James Fabian Machin, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Signature_______________________________________ Date____________________ 2 Abstract Weird fiction is a mode in the Gothic lineage, cognate with horror, particularly associated with the early twentieth-century pulp writing of H. P. Lovecraft and others for Weird Tales magazine. However, the roots of the weird lie earlier and late-Victorian British and Edwardian writers such as Arthur Machen, Count Stenbock, M. P. Shiel, and John Buchan created varyingly influential iterations of the mode. This thesis is predicated on an argument that Lovecraft’s recent rehabilitation into the western canon, together with his ongoing and arguably ever-increasing impact on popular culture, demands an examination of the earlier weird fiction that fed into and resulted in Lovecraft’s work. Although there is a focus on the literary fields of the fin de siècle and early twentieth century, by tracking the mutable reputations and critical regard of these early exponents of weird fiction, this thesis engages with broader contextual questions of cultural value and distinction; of notions of elitism and popularity, tensions between genre and literary fiction, and the high/low cultural divide allegedly precipitated by Modernism. 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: The Wyrd, the Weird-like, and the Weird .............................. -

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J_J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 PORTLAND, OR 97211 AUGUST, 1983 —VOL.12, NO.3 WHOLE NUMBER 98 PHONE: (503) 282-0381 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR PUBLISHED QUARTERLY FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. SINGLE COPY - $2.00 ALIEN THOUGHTS BY THE EDITOR.9 THE TREASURE OF THE SECRET C0RDWAINER by j.j. pierce.8 LETTERS.15 INTERIOR ART-- ROBERT A. COLLINS CHARLES PLATT IAN COVELL E. F. BLEILER ALAN DEAN FOSTER SMALL PRESS NOTES ED ROM WILLIAM ROTLSER-8 BY THE EDITOR.92 KERRY E. DAVIS RAYMOND H. ALLARD-15 ARNIE FENNER RICHARD BRUNING-20199 RONALD R. LAMBERT THE VIVISECTOR ATOM-29 F. M. BUSBY JAMES MCQUADE-39 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER.99 ELAINE HAMPTON UNSIGNED-35 J.R. MADDEN GEORGE KOCHELL-38,39,90,91 RALPH E. VAUGHAN UNSIGNED-96 ROBERT BLOCH TWONG, TWONG SAID THE TICKTOCKER DARRELL SCHWEITZER THE PAPER IS READY DONN VICHA POEMS BY BLAKE SOUTHFORK.50 HARLAN ELLISON CHARLES PLATT THE ARCHIVES BOOKS AND OTHER ITEMS RECEIVED OTHER VOICES WITH DESCRIPTION, COMMENTARY BOOK REVIEWS BY AND OCCASIONAL REVIEWS.51 KARL EDD ROBERT SABELLA NO ADVERTISING WILL BE ACCEPTED RUSSELL ENGEBRETSON TEN YEARS AGO IN SF - SUTER,1973 JOHN DIPRETE BY ROBERT SABELLA.62 Second Class Postage Paid GARTH SPENCER at Portland, OR 97208 THE STOLEN LAKE P. MATHEWS SHAW NEAL WILGUS ALLEN VARNEY Copyright (c) 1983 by Richard E. MARK MANSELL Geis. One-time rights only have ALMA JO WILLIAMS been acquired from signed or cred¬ DEAN R. -

Lost Races, Which in Turn Are Often Utopian Fictions

1 About Catalogue VIII We visited with George Locke recently, who’s doing well, and picked up six boxes of Lost Race novels. The following catalogue, our ninth, is the result. We’ve taken a little time out to read a chapter here and there of some of the stories herein. Some are pretty good, some are quite poor. Either way, they deserve to be remembered. Many of the titles herewith are genuinely rare. We’ve located copies of all of them somewhere, mostly in libraries. Many are in Blieler’s Checklist, nearly all are in Locke’s Spectrum, as they should be as George’s collection is where most of the copies have been plucked from. John Clute and John Grants’ Encyclopaedia has been essential too in the cataloguing, as has Lloyd Currey’s extensive stock. George collected these over several decades, and it would be an injustice to not commemorate that in some way. The very fact that each title has included a brief synopsis is testament to the import of George’s contribution to the genre. There are 28 items in this catalogue, all revolving around Lost Races, which in turn are often utopian fictions. Supplementary to these items are a few dozen books grouped into one lot primarily for ease of cataloguing and value. They would make an excellent starter for a collector with an interest in the area. The Lost Race subgenre has certainly tailed off over the last few decades. Greater exploration beyond and within earth’s bounds, satellite mapping and easier communication has meant that the notion of finding a lost race on or within earth is less plausible and stories therefore become more twee. -

Heuristic Futures: Reading the Digital Humanities Through Science Fiction

Heuristic Futures: Reading the Digital Humanities through Science Fiction A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences by Joseph William Dargue 2015 B.A. (Hons.), Lancaster University, 2006 M.A., Royal Holloway, University of London, 2008 Committee Chair: Laura Micciche, Ph.D. Abstract This dissertation attempts to highlight the cultural relationship between the digital humanities and science fiction as fields of inquiry both engaged in the development of humanistic perspectives in increasingly global digital contexts. Through analysis of four American science fiction novels, the work is concerned with locating the genre’s pedagogical value as a media form that helps us adapt to the digital present and orient us toward a digital future. Each novel presents a different facet of digital humanities practices and/or discourses that, I argue, effectively re-evaluate the humanities (particularly traditional literary studies and pedagogy) as a set of hybrid disciplines that leverage digital technologies and the sciences. In Pat Cadigan’s Synners (1993), I explore issues of production, consumption, and collaboration, as well as the nature of embodied subjectivity, in a reality codified by the virtual. The chapters on Richard Powers’ Galatea 2.2 (1995) and Vernor Vinge’s Rainbows End (2006) are concerned with the passing of traditional humanities practices and the evolution of the institutions they are predicated on (such as the library and the composition classroom) in the wake of the digital turn. -

Unless Otherwise Stated, Place of Publication Is London

Notes Unless otherwise stated, place of publication is London. 1 Introduction 1. Julia Briggs, Night Visitors: The Rise of the English Ghost Story (Faber, 1977), pp. 16-17, 19, 24. 2. See my Christian Fantasy: From 1200 to the Present (Macmillan, 1992). 3. Sidney, An Apologie for Poetrie (1595), repr. in G. Gregory Smith, ed., Elizabethan Critical Essays, 2 vols. (Oxford University Press, 1904), I, 156. 4. See my 'The Elusiveness of Fantasy', in Olena H. Saciuk, ed., The Shape of the Fantastic (Westport: Greenwood, 1990), pp. 54-5. 5. J. R. R. Tolkien, 'On Fairy Stories' (1938; enlarged in his Tree and Leaf (Allen and Unwin, 1964); C. S. Lewis, 'On Science Fiction' (1955), repr. in Lewis, Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories, ed. W. Hooper (Bles, 1966), pp. 59-73; Rosemary Jackson, Fantasy: The Literature of Subver sion (Methuen, 1981); Ann Swinfen, In Defence of Fantasy: A Study of the Genre in English and American Literature Since 1945 (Routledge, 1984). 6. Brian Attebery, Strategies of Fantasy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992), pp. 12-14. 7. The name is first applied to a literary kind by Herbert Read in English Prose Style (1928); though E. M. Forster had just devoted a chapter of Aspects of the Novel (1927) to 'Fantasy' as a quality of vision. 8. See Brian Stableford, ed., The Dedalus Book of Femmes Fatales (Sawtry, Cambs.: Dedalus, 1992), pp. 20-4. 2 The Origins of English Fantasy 1. See E. S. Hartland, ed., English Fairy and Other Folk Tales (Walter Scott, 1890), pp. x-xxi; Katharine M.