Redefining Humanity in Science Fiction: the Alien from an Ecofeminist Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Place in the Universe

TABLE OF CONTENTS Your place in the Universe Introduction: Your place in the universe .............................................1 Part 1: Detect an alien world and find out what it’s like Introduction............................................................................................................................... 11 Activity.1.1................................................................................................................................ 13 Activity.1.2................................................................................................................................ 22 Activity.1.3................................................................................................................................ 31 Activity.1.4................................................................................................................................ 46 Part 2: Looking for a habitable planet...and life Introduction............................................................................................................................... 61 Activity.2.1................................................................................................................................ 64 Activity.2.2................................................................................................................................ 67 Activity.2.3................................................................................................................................ 71 Activity.2.4............................................................................................................................... -

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

Biophilia, Gaia, Cosmos, and the Affectively Ecological

vital reenchantments Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-profit press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afloat. Contri- butions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t find a welcoming port elsewhere. Our ad- venture is not possible without your support. Vive la Open Access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) vital reenchantments: biophilia, gaia, cosmos, and the affectively ecological. Copyright © 2019 by Lauren Greyson. This work carries a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and transformation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http://creativecommons.org/li- censes/by-nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2019 by punctum books, Earth, Milky Way. https://punctumbooks.com ISBN-13: 978-1-950192-07-6 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-950192-08-3 (ePDF) lccn: 2018968577 Library of Congress Cataloging Data is available from the Library of Congress Editorial team: Casey Coffee and Eileen A. -

ECOMYSTICISM: MATERIALISM and MYSTICISM in AMERICAN NATURE WRITING by DAVID TAGNANI a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfill

ECOMYSTICISM: MATERIALISM AND MYSTICISM IN AMERICAN NATURE WRITING By DAVID TAGNANI A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of English MAY 2015 © Copyright by DAVID TAGNANI, 2015 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by DAVID TAGNANI, 2015 All Rights Reserved ii To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of DAVID TAGNANI find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________________ Christopher Arigo, Ph.D., Chair ___________________________________________ Donna Campbell, Ph.D. ___________________________________________ Jon Hegglund, Ph.D. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank my committee members for their hard work guiding and encouraging this project. Chris Arigo’s passion for the subject and familiarity with arcane source material were invaluable in pushing me forward. Donna Campbell’s challenging questions and encyclopedic knowledge helped shore up weak points throughout. Jon Hegglund has my gratitude for agreeing to join this committee at the last minute. Former committee member Augusta Rohrbach also deserves acknowledgement, as her hard work led to significant restructuring and important theoretical insights. Finally, this project would have been impossible without my wife Angela, who worked hard to ensure I had the time and space to complete this project. iv ECOMYSTICISM: MATERIALISM AND MYSTICISM IN AMERICAN NATURE WRITING Abstract by David Tagnani, Ph.D. Washington State University May 2015 Chair: Christopher Arigo This dissertation investigates the ways in which a theory of material mysticism can help us understand and synthesize two important trends in the American nature writing—mysticism and materialism. -

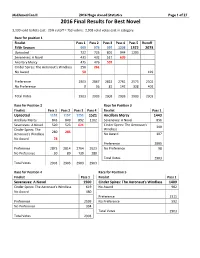

2016 Statistics Document

MidAmeriCon II 2016 Hugo Award Statistics Page 1 of 27 2016 Final Results for Best Novel 3,130 valid ballots cast. 25% cutoff = 753 voters. 2,903 valid votes cast in category. Race for position 1 Finalist Pass 1 Pass 2 Pass 3 Pass 4 Pass 5 Runoff Fifth Season 969 973 997 1208 1372 2073 Uprooted 722 725 801 944 1203 Seveneves: A Novel 431 432 517 609 Ancillary Mercy 475 476 507 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 256 261 No Award 50 429 Preference 2903 2867 2822 2761 2575 2502 No Preference 0 36 81 142 328 401 Total Votes 2903 2903 2903 2903 2903 2903 Race for Position 2 Race for Position 3 Finalist Pass 1 Pass 2 Pass 3 Pass 4 Finalist Pass 1 Uprooted 1152 1157 1251 1521 Ancillary Mercy 1443 Ancillary Mercy 843 849 892 1102 Seveneves: A Novel 856 Seveneves: A Novel 520 523 621 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's 399 Cinder Spires: The Windlass 280 285 Aeronaut's Windlass No Award 107 No Award 78 Preference 2805 Preference 2873 2814 2764 2623 No Preference 98 No Preference 30 89 139 280 Total Votes 2903 Total Votes 2903 2903 2903 2903 Race for Position 4 Race for Position 5 Finalist Pass 1 Finalist Pass 1 Seveneves: A Novel 1500 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 1409 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 619 No Award 902 No Award 480 Preference 2311 Preference 2599 No Preference 592 No Preference 304 Total Votes 2903 Total Votes 2903 MidAmeriCon II 2016 Hugo Award Statistics Page 2 of 27 2016 Final Results for Best Novella 3,130 valid ballots cast. -

Lightspeed Magazine, Issue 66 (November 2015)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 66, November 2015 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial, November 2015 SCIENCE FICTION Here is My Thinking on a Situation That Affects Us All Rahul Kanakia The Pipes of Pan Brian Stableford Rock, Paper, Scissors, Love, Death Caroline M. Yoachim The Light Brigade Kameron Hurley FANTASY The Black Fairy’s Curse Karen Joy Fowler When We Were Giants Helena Bell Printable Toh EnJoe (translated by David Boyd) The Plausibility of Dragons Kenneth Schneyer NOVELLA The Least Trumps Elizabeth Hand NOVEL EXCERPTS Chimera Mira Grant NONFICTION Artist Showcase: John Brosio Henry Lien Book Reviews Sunil Patel Interview: Ernest Cline The Geek’s Guide to the Galaxy AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS Rahul Kanakia Karen Joy Fowler Brian Stableford Helena Bell Caroline M. Yoachim Toh EnJoe Kameron Hurley Kenneth Schneyer Elizabeth Hand MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Upcoming Events Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks About the Lightspeed Team Also Edited by John Joseph Adams © 2015 Lightspeed Magazine Cover by John Brosio www.lightspeedmagazine.com Editorial, November 2015 John Joseph Adams | 712 words Welcome to issue sixty-six of Lightspeed! Back in August, it was announced that both Lightspeed and our Women Destroy Science Fiction! special issue specifically had been nominated for the British Fantasy Award. (Lightspeed was nominated in the Periodicals category, while WDSF was nominated in the Anthology category.) The awards were presented October 25 at FantasyCon 2015 in Nottingham, UK, and, alas, Lightspeed did not win in the Periodicals category. But WDSF did win for Best Anthology! Huge congrats to Christie Yant and the rest of the WDSF team, and thanks to everyone who voted for, supported, or helped create WDSF! You can find the full list of winners at britishfantasysociety.org. -

The War of the Worlds Postcolonialism, Americanism, and Terrorism in Modern Science Fiction Film

Durkstra 4167430 | 1 The War of the Worlds Postcolonialism, Americanism, and Terrorism in Modern Science Fiction Film Sytse Durkstra English Language and Culture Supervisor | Chris Louttit Sytse Durkstra | s4167430 | Email [email protected] Durkstra 4167430 | 2 ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND CULTURE Teacher who will receive this document: Chris Louttit Title of document: The War of the Worlds: Postcolonialism, Americanism, and Terrorism in Modern Science Fiction Film Name of course: BA Thesis English Language and Culture Date of submission: 15 June 2015 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Sytse Durkstra Student number: 4167430 Durkstra 4167430 | 3 And this Thing I saw! How can I describe it? A monstrous tripod, higher than many houses, striding over the young pine trees, and smashing them aside in its career; a walking engine of glittering metal, reeling now across the heather, articulate ropes of steel dangling from it, and the clattering tumult of its passage mingling with the riot of the thunder. A flash, and it came out vividly, heeling over one way with two feet in the air, to vanish and reappear almost instantly, as it seemed with the next flash, a hundred yards nearer. - H.G. Wells, The War of the Worlds But who shall dwell in these worlds if they be inhabited? . Are we or they Lords of the World? . And how are all things made for man? - Kepler In our obsession with antagonisms of the moment, we often forget how much unites all the members of humanity. -

Views That Barnes Has Given, Wherein

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Darker Matters: Racial Theorizing through Alternate History, Transhistorical Black Bodies, and Towards a Literature of Black Mecha in the Science Fiction Novels of Steven Barnes Alexander Dumas J. Brickler IV Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DARKER MATTERS: RACIAL THEORIZING THROUGH ALTERNATE HISTORY, TRANSHISTORICAL BLACK BODIES, AND TOWARDS A LITERATURE OF BLACK MECHA IN THE SCIENCE FICTION NOVELS OF STEVEN BARNES By ALEXANDER DUMAS J. BRICKLER IV A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Alexander Dumas J. Brickler IV defended this dissertation on April 16, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jerrilyn McGregory Professor Directing Dissertation Delia Poey University Representative Maxine Montgomery Committee Member Candace Ward Committee Member Dennis Moore Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Foremost, I have to give thanks to the Most High. My odyssey through graduate school was indeed a long night of the soul, and without mustard-seed/mountain-moving faith, this journey would have been stymied a long time before now. Profound thanks to my utterly phenomenal dissertation committee as well, and my chair, Dr. Jerrilyn McGregory, especially. From the moment I first perused the syllabus of her class on folkloric and speculative traditions of Black authors, I knew I was going to have a fantastic experience working with her. -

Its Influence in the Bioclimatic Regions of Trans-Saharan Africa

Proceedings: 4th Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 1965 FIG. 1. Elephant in Queen Elizabeth Park, Uganda. SubhU'mid Wooded Savanna. From a color slide courtesy Dr. P. R. Hill, Pietermaritzburg. FIG. 2. Leopard in Acacia, Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. Subarid Wooded Savanna. From a color slide courtesy Dr. P. R. Hill, Pietermaritzburg. 6 Fire-as Master and Servant: Its Influence in the Bioclimatic Regions of Trans-Saharan Africa JOHN PHILLIPS* DESPITE MAN's remarkable advances in so many fields of endeavor in Trans-Saharan Africa, there is still much he does not know regarding some of the seemingly simple matters of life and living in the "Dark" Continent: One of these blanks in our knowldege is how the most effectively to thwart fire as an uncontrolled destroyer of vegetation and how best to use it to our own advantage. We know fire as a master, we have learned some thing about fire as a servant-but we still have much to do before we can direct this servant so as to win its most effective service. I review-against a background of the literature and a personal ex perience .of over half a century-some of the matters of prime inter est and significance in the role and the use of fire in Trans-Saharan Africa. These include, inter alia, the sins of the master and the merits of the servant, in a range of bioclimatic regions from the humid for ests, through the various gradations of aridity of the wooded savanna to .the subdesert. In an endeavor to discuss the whole subject objectively and sys tematically, I have dealt with the effects of fire upon vegetation, upon animal associates, upon aerillI factors and upon the complex fac tors of the soil. -

Prototype of Sunken Place: Reading Jordan Peele’S Get out Through Octavia Butler’S Kindred As Black Science Fiction and Speculative Fiction Narratives

Prototype of Sunken Place: Reading Jordan Peele’s Get Out through Octavia Butler’s Kindred as Black Science Fiction and Speculative Fiction Narratives BRITNEY HENRY Science fiction and speculative fiction have imagined new worlds, species, and technologies that have influenced individuals and societies. These genres have a significant space within American popular culture as “popular culture is woven deeply and intimately into the fabric of our everyday lives. While it may be tempting to imagine such amusements and attachments as apolitical, popular culture reflects and plays a significant role in contouring how we think, feel and act in the world for better and often for worse” (Mueller et al. 70). Science fiction and speculative fiction are not apolitical. These genres within the space of Black culture have illustrated forgotten or distorted historical events within American culture. America has a history of othering the Black body and the alterity of this body comes in the form of systematic oppression and racism. History has inflicted serious trauma and damage mentally and physically on Black bodies. I use “body” instead of “person” here because of the objectification of the body without regards to personhood which Hortense Spillers refers to as, “a territory of cultural and political maneuver” (67). Furthermore, the flesh and body are conceived as being separate. The body can become an object and dehumanized whereas the flesh takes the impact of the pain being inflicted. Black flesh has been abused, sexually degraded, and scientifically exploited throughout history. Mark Dery furthers this notion stating: in a very real sense, [Black people] are the descendants of alien abductees; they inhabit a sci-fi nightmare in which unseen but no less impassable force fields of intolerance frustrate their movements; official histories undo what BRITNEY HENRY is doctoral student of English Literature at The University of Delaware. -

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe. -

Stress-Testing Alien Invasion

STRESS-TESTING ALIEN INVASION ARE FINANCIAL MARKETS MISPRICING THE BIGGEST SYSTEMIC RISK EVER? “Five kinds of extreme environmental risks exist (…) An invasion by non-peace seeking aliens that seek to remove the planet’s resources or enslave/exterminate human life.” TOWERS WATSON, GLOBAL INVESTMENT CONSULTING FIRM, 2014 “Extra-terrestrial environmentalists could be so appalled by our planet polluting ways that they view us as a threat to the intergalactic ecosystem and decide to destroy us” NASA & PENNSYLVANIA UNIVERSITY 2011 “And yet I ask you, is not an alien force already among us?” RONALD REAGAN IN A SPEECH TO THE UNITED NATIONS, 1987 “Where are they?” NICK BOSTROM, PROFESSOR OXFORD UNIVERSITY, 2016 “Earth could be at risk from massive ships which could try to colonise our planet and plunder our resources” STEPHEN HAWKING, 2014 This report is the first report of the FERMI’nvesting Initiative (Fii), the research program launched by the 2°Investing Initiative designed to track financial risks related to the invasion of aliens, in partnership with Extra Terrestrial Advisors (ET Advisors), the leading consultancy on aliens risks. Authors: Jakob Thomä, Stan Dupre. The FERMI’nvesting research is provided free of charge and Fii does not seek any direct or indirect financial compensation for its research. Fii is not an investment adviser, and makes no representation regarding the advisability of investing in any particular company or investment fund or other vehicle. A decision to invest in any such investment fund or other entity should not be made in reliance on any of the statements set forth in this publication.