"Well, Watson, What Do You Make of It?": an In-Depth Look at Sherlock Holmes As a Hero

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Red-Headed League (The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Red-Headed League (The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle I had called upon my friend, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, one day in the autumn of last year and found him in deep conversation with a very stout, florid-faced, elderly gentleman with fiery red hair. With an apology for my intrusion, I was about to withdraw when Holmes pulled me abruptly into the room and closed the door behind me. "You could not possibly have come at a better time, my dear Watson," he said cordially. "I was afraid that you were engaged." "So I am. Very much so." "Then I can wait in the next room." "Not at all. This gentleman, Mr. Wilson, has been my partner and helper in many of my most successful cases, and I have no doubt that he will be of the utmost use to me in yours also." The stout gentleman half rose from his chair and gave a bob of greeting, with a quick little questioning glance from his small fat-encircled eyes. "Try the settee," said Holmes, relapsing into his armchair and putting his fingertips together, as was his custom when in judicial moods. "I know, my dear Watson, that you share my love of all that is bizarre and outside the conventions and humdrum routine of everyday life. You have shown your relish for it by the enthusiasm which has prompted you to chronicle, and, if you will excuse my saying so, somewhat to embellish so many of my own little adventures." "Your cases have indeed been of the greatest interest to me," I observed. -

Sherlock Holmes: the Final Adventure the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2014, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Brian Vaughn (left) and J. Todd Adams in Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure, 2015. Contents Sherlock InformationHolmes: on the PlayThe Final Synopsis 4 Characters 5 About the AdventurePlaywright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play The Final Adventures of Sherlock Holmes? 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure The play begins with the announcement of the death of Sherlock Holmes. It is 1891 London; and Dr. Watson, Holmes’s trusty colleague and loyal friend, tells the story of the famous detective’s last adventure. -

A Thematic Reading of Sherlock Holmes and His Adaptations

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2016 Crime and culture : a thematic reading of Sherlock Holmes and his adaptations. Britney Broyles University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Asian American Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Broyles, Britney, "Crime and culture : a thematic reading of Sherlock Holmes and his adaptations." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2584. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2584 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRIME AND CULTURE: A THEMATIC READING OF SHERLOCK HOLMES AND HIS ADAPTATIONS By Britney Broyles B.A., University of Louisville, 2008 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Comparative Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, KY December 2016 Copyright 2016 by Britney Broyles All rights reserved CRIME AND CULTURE: A THEMATIC READING OF SHERLOCK HOLMES AND HIS ADAPTATIONS By Britney Broyles B.A., University of Louisville, 2008 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 Dissertation Approved on November 22, 2016 by the following Dissertation Committee: Dr. -

Sherlock Holmes and the Nazis: Fifth Columnists and the People’S War in Anglo-American Cinema, 1942-1943

Sherlock Holmes and the Nazis: Fifth Columnists and the People’s War in Anglo-American Cinema, 1942-1943 Smith, C Author post-print (accepted) deposited by Coventry University’s Repository Original citation & hyperlink: Smith, C 2018, 'Sherlock Holmes and the Nazis: Fifth Columnists and the People’s War in Anglo-American Cinema, 1942-1943' Journal of British Cinema and Television, vol 15, no. 3, pp. 308-327. https://dx.doi.org/10.3366/jbctv.2018.0425 DOI 10.3366/jbctv.2018.0425 ISSN 1743-4521 ESSN 1755-1714 Publisher: Edinburgh University Press This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Edinburgh University Press in Journal of British Cinema and Television. The Version of Record is available online at: http://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.3366/jbctv.2018.0425. Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. This document is the author’s post-print version, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer-review process. Some differences between the published version and this version may remain and you are advised to consult the published version if you wish to cite from it. Sherlock Holmes and the Nazis: Fifth Columnists and the People’s War in Anglo-American Cinema, 1942-1943 Christopher Smith This article has been accepted for publication in the Journal of British Film and Television, 15(3), 2018. -

Cartoon Animals Vs. Actual Russians: Russian Television and the Dynamics of Global Cultural Exchange 2021

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Jeffrey Brassard Cartoon Animals vs. Actual Russians: Russian Television and the Dynamics of Global Cultural Exchange 2021 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/16243 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Brassard, Jeffrey: Cartoon Animals vs. Actual Russians: Russian Television and the Dynamics of Global Cultural Exchange. In: VIEW. Journal of European Television History and Culture, Jg. 10 (2021), Nr. 19, S. 4– 15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/16243. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.18146/view.252 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0/ Attribution - Share Alike 4.0/ License. For more information see: Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ volume 10 issue 19/2021 CARTOON ANIMALS VS. ACTUAL RUSSIANS RUSSIAN TELEVISION AND THE DYNAMICS OF GLOBAL CULTURAL EXCHANGE Jeffrey Brassard University of Alberta [email protected] Abstract: Despite continual improvements in production and writing quality, live-action Russian series have fared poorly in the global market. While many deals have been struck, Western remakes of Russian series have failed to appear, and live-action programs have failed to find mainstream audiences outside of Russia. Russian animated series, on the other hand, have enjoyed global success. The success and failure of different types of Russian series in the global media market suggests that many of the central problems of cultural exchange remain. -

The Mysterious Moor

The Hound of the Baskervilles The Mysterious Moor The Lure of the Moor We often think of the English countryside as a pleasant land of forest and pasture, curbed by neat hedgerows and orderly gardens. But at higher elevations, a wilder landscape rears its head: the moor. Little thrives in any moor’s windy, rainy climate, leaving a rolling expanse of infertile wetlands dominated by tenacious gorse and grasses. Its harsh, chaotic weather, so inhospitable to human life, has nonetheless proved fertile ground for the many writers who’ve set their stories on its gloomy plain. A native of nearby Dorchester, Thomas Hardy set The Return of the Native, Tess of the D’Urbervilles, and other novels on the wild, haunted moor that D.H. Lawrence called “the real stuff of tragedy.” In Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, the violent, passionate Catherine and Heathcliff seem to echo the moors that surround them. Dame Agatha Christie booked herself into the “large, dreary” Moorland Hotel to finish work on The Mysterious Affair at Styles, while Dartmoor is the setting for The Sittaford Mystery (1931). The moor’s atmospheric weather and desolate landscape lend an air of tragedy and mystery to all of these tales, as they do to The Hound of the Baskervilles. On Dartmoor’s windswept plain, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle found the legendary roots and the creepy backdrop of his most famous story. He took many liberties, changing the names of geographic localities and altering distances to suit his story, but even today, Sherlock Holmes fans are known to set out across the moor in search of the real counterparts of the fictional locale where the story took place. -

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

Exsherlockholmesthebakerstre

WRITTEN BY ERIC COBLE ADAPTED FROM THE GRAPHIC NOVELS BY TONY LEE AND DAN BOULTWOOD © Dramatic Publishing Company Drama/Comedy. Adapted by Eric Coble. From the graphic novels by Tony Lee and Dan Boultwood. Cast: 5 to 10m., 5 to 10w., up to 10 either gender. Sherlock Holmes is missing, and the streets of London are awash with crime. Who will save the day? The Baker Street Irregulars—a gang of street kids hired by Sherlock himself to help solve cases. Now they must band together to prove not only that Sherlock is not dead but also to find the mayor’s missing daughter, untangle a murder mystery from their own past, and face the masked criminal mastermind behind it all—a bandit who just may be the brilliant evil Moriarty, the man who killed Sherlock himself! Can a group of orphans, pickpockets, inventors and artists rescue the people of London? The game is afoot! Unit set. Approximate running time: 80 minutes. Code: S2E. “A reminder anyone can rise above their backgrounds and past, especially when someone else respectable also respects and trusts them.” —www.broadwayworld.com “A classic detective story with villains, cops, mistaken identities, subterfuge, heroic acts, dangerous situations, budding love stories and twists and turns galore.” —www.onmilwaukee.com Cover design: Cristian Pacheco. ISBN: 978-1-61959-056-4 Dramatic Publishing Your Source for Plays and Musicals Since 1885 311 Washington Street Woodstock, IL 60098 www.dramaticpublishing.com 800-448-7469 © Dramatic Publishing Company Sherlock Holmes: The Baker Street Irregulars By ERIC COBLE Based on the graphic novel series by TONY LEE and DAN BOULTWOOD Dramatic Publishing Company Woodstock, Illinois • Australia • New Zealand • South Africa © Dramatic Publishing Company *** NOTICE *** The amateur and stock acting rights to this work are controlled exclusively by THE DRAMATIC PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC., without whose permission in writing no performance of it may be given. -

Sherlock Holmes Jazz Age Parodies and Pastiches I : 1920-1924 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SHERLOCK HOLMES JAZZ AGE PARODIES AND PASTICHES I : 1920-1924 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bill Peschel | 368 pages | 04 May 2018 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781717112972 | English | none Sherlock Holmes Jazz Age Parodies and Pastiches I : 1920-1924 PDF Book While Holmes and Watson, and their non-copyrightable counterparts, have appeared in numerous comic strips, this was the first full-length case to appear The magazine published so many Foster; Joseph D. Lucas Why Read at All? July 30, This biography, published in , draws on George Fletcher's lifetime of research, including interviews with many of witnesses and residents of Rugeley, England. Visiting the Alistair house, she is told that Cecily's mother is not receiving, and that Cecily has moved away. Watson begins to suspect that Holmes is alive. They pay a visit to the Hall's former residents, the Pringles, and Holmes is interested in learning of periods of time when they were away from the house. Sayers and her amateur detective, Lord Peter Wimsey. Bailey takes him home to meet a friend who never arrives. Peschel Press' tag cloud. April 12, Milne, P. In addition, this book contains several pieces relating to Conan Doyle without reference to Holmes. Barrie The Sleuths - O. Experience Christie in a new way. Permitted to enter heaven, he deduces the nature of the deaths of Watson and his wife, and inquires into the colour-coding of haloes. Holmes prevents a human sacrifice and Vernier gives a lesson on Onanism. When she learns that Spock, too, has been dreaming, she questions him, and learns of his dark side. -

Is Castro's Cuba a Budding Narcostate?

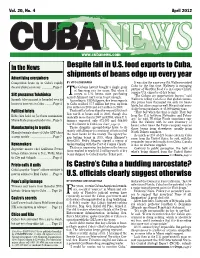

Vol. 20, No. 4 April 2012 In the News Despite fall in U.S. food exports to Cuba, Advertising everywhere shipments of beans edge up every year Competition heats up in Cuba’s rapidly BY VITO ECHEVARRÍA It was also the same year Pat Wallesen visited decentralizing economy ................Page 3 he Cubans haven’t bought a single grain Cuba for the first time. Wallesen is managing of American rice for years. But when it partner of WestStar Food Co. in Corpus Christi, Tcomes to U.S. beans, state purchasing a major U.S. exporter of dry beans. SEC pressures Telefónica agency Alimport can’t seem to get enough. “The Cubans are opportunistic buyers,” said Spanish telecom giant is hounded over its According to USDA figures, dry bean exports Wallesen, telling CubaNews that global commo- business interests in Cuba ............Page 4 to Cuba reached $7.7 million last year, up from dity prices have fluctuated not only for beans lately, but other crops as well. He put total annu- $5.6 million in 2010 and $4.3 million in 2009. al dry bean purchases at 45,000 metric tons. Political briefs That’s still a lot less than the record $10.9 mil- “They buy when the time is right. They buy lion worth of beans sold in 2006, though dra- from the U.S. between November and Febru- Rubio lifts hold on Jacobson nomination; matically more than in 2007 and 2008, when U.S. Miami-Dade proposal under fire ...Page 5 ary,” he said. WestStar Foods sometimes sup- farmers exported only $73,000 and $68,000 plies the Cubans with its own inventory of worth of beans to Cuba (see chart, page 3). -

ENDER's GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third

ENDER'S GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third "I've watched through his eyes, I've listened through his ears, and tell you he's the one. Or at least as close as we're going to get." "That's what you said about the brother." "The brother tested out impossible. For other reasons. Nothing to do with his ability." "Same with the sister. And there are doubts about him. He's too malleable. Too willing to submerge himself in someone else's will." "Not if the other person is his enemy." "So what do we do? Surround him with enemies all the time?" "If we have to." "I thought you said you liked this kid." "If the buggers get him, they'll make me look like his favorite uncle." "All right. We're saving the world, after all. Take him." *** The monitor lady smiled very nicely and tousled his hair and said, "Andrew, I suppose by now you're just absolutely sick of having that horrid monitor. Well, I have good news for you. That monitor is going to come out today. We're going to just take it right out, and it won't hurt a bit." Ender nodded. It was a lie, of course, that it wouldn't hurt a bit. But since adults always said it when it was going to hurt, he could count on that statement as an accurate prediction of the future. Sometimes lies were more dependable than the truth. "So if you'll just come over here, Andrew, just sit right up here on the examining table. -

Not Your Grandfather's Sherlock Holmes

d “nOt YOuR GRandFatHeR’S SHeRlOCk HOlMeS”: Guy Ritchie’s 21st Century Reboot of a 19th Century british Icon Ashley Liening Sherlock Holmes “has enjoyed the most vigorous afterlife of any fictional character” posits thomas leitch, adaptation scholar and author of Film Adaptation and Its Discontents (leitch 207). Indeed, a franchise has been built around Sir arthur Conan doyle’s quirky detective, so much so that Sherlock Holmes has become one of the most adapted literary figures of all time, outnumbered only by Frankenstein’s monster, tarzan, and dracula (207). Clare Parody asserts, “Franchise practice has produced and surrounded some of the highest grossing and best-known fictional texts, characters, plots, and worlds of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries,” and Sherlock Holmes is no exception (211). From 1900 till the present day, Sherlock Holmes has been portrayed by “nearly 100 actors, in over 200 films, from more than a dozen different countries,” and it does not appear like “Sir arthur Conan doyle’s violin- playing, pipe-smoking, cocaine-injecting sleuth” is going any- where anytime soon (Cook 31). In fact, the twenty-first century has experienced a resurgence in more “straightforward” Holmes adaptations, namely bbC’s Sherlock (2010), which aired in three ninety-minute episodes and portrays a tech-savvy twenty-first century Holmes, and Guy Ritchie’s 2009 and 2011 35 big screen adaptations, the latter of which will be the focus of this essay. I aim to explore the ways in which Guy Ritchie’s Sher lock Holmes (2009) adaptation, while inextricably bound to Conan doyle’s storytelling franchise, diverges from its prede- cessors in that it is not an amalgamation of other Holmes adap- tations.