Not Your Grandfather's Sherlock Holmes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Red-Headed League (The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

The Red-Headed League (The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle I had called upon my friend, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, one day in the autumn of last year and found him in deep conversation with a very stout, florid-faced, elderly gentleman with fiery red hair. With an apology for my intrusion, I was about to withdraw when Holmes pulled me abruptly into the room and closed the door behind me. "You could not possibly have come at a better time, my dear Watson," he said cordially. "I was afraid that you were engaged." "So I am. Very much so." "Then I can wait in the next room." "Not at all. This gentleman, Mr. Wilson, has been my partner and helper in many of my most successful cases, and I have no doubt that he will be of the utmost use to me in yours also." The stout gentleman half rose from his chair and gave a bob of greeting, with a quick little questioning glance from his small fat-encircled eyes. "Try the settee," said Holmes, relapsing into his armchair and putting his fingertips together, as was his custom when in judicial moods. "I know, my dear Watson, that you share my love of all that is bizarre and outside the conventions and humdrum routine of everyday life. You have shown your relish for it by the enthusiasm which has prompted you to chronicle, and, if you will excuse my saying so, somewhat to embellish so many of my own little adventures." "Your cases have indeed been of the greatest interest to me," I observed. -

Sherlock Holmes: the Final Adventure the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

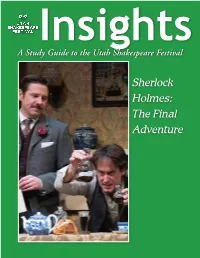

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2014, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Brian Vaughn (left) and J. Todd Adams in Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure, 2015. Contents Sherlock InformationHolmes: on the PlayThe Final Synopsis 4 Characters 5 About the AdventurePlaywright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play The Final Adventures of Sherlock Holmes? 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: Sherlock Holmes: The Final Adventure The play begins with the announcement of the death of Sherlock Holmes. It is 1891 London; and Dr. Watson, Holmes’s trusty colleague and loyal friend, tells the story of the famous detective’s last adventure. -

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

The District Messenger

THE DISTRICT MESSENGER The Newsletter of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE no. 154 30th September 1995 Jeremy Brett died on the 12th September, not of a broken heart, but of an overworked heart. He had come to terms with his precarious condition, and knew that his only chance of cardiac stability was a heart transplant, an option he had considered and rejected. The cardiomyopathy was not correctly diagnosed until comparatively late, but it was this rather than his manic- depression that made his later performances as Sherlock Holmes so uneven, though the tabloids made the most of the latter. Jeremy Brett played Holmes in 41 television productions and one stage play. For more than three- quarters of the time he was a great Sherlock Holmes. In Pace Requiescat. The next issue of The Sherlock Holmes Gazette will be a Jeremy Brett memorial issue. Look out for it. Admirers of John Doubleday's famous statue of Holmes in Meiringen, Switzerland, will be pleased to learn that the sculptor has been persuaded to produce a miniature version in cold-cast bronze on a mahogany base. The height of the statuette, without the base, is 6½” (160mm), and the price is a maximum of £77.55 including VAT (plus postage of £4.45 = total £82.00). It's available from Albert Kunz, 20 Highfield Road, Chislehurst, Kent BR7 6QZ (phone 01689 836256). Cheques should be payable to A. Kunz; they won't be cashed until the statuettes are sent out. As mentioned in the last DM, Calabash Press (Barbara & Christopher Roden, Ashcroft, 2 Abbottsford Drive, Penyffordd, Chester CH4 OJG) will issue its first publication on 15th October, The Tangled SkeinSkein by David Stuart Davies, whose first, very limited edition is no longer obtainable. -

A Thematic Reading of Sherlock Holmes and His Adaptations

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2016 Crime and culture : a thematic reading of Sherlock Holmes and his adaptations. Britney Broyles University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Asian American Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Broyles, Britney, "Crime and culture : a thematic reading of Sherlock Holmes and his adaptations." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2584. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2584 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CRIME AND CULTURE: A THEMATIC READING OF SHERLOCK HOLMES AND HIS ADAPTATIONS By Britney Broyles B.A., University of Louisville, 2008 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Comparative Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, KY December 2016 Copyright 2016 by Britney Broyles All rights reserved CRIME AND CULTURE: A THEMATIC READING OF SHERLOCK HOLMES AND HIS ADAPTATIONS By Britney Broyles B.A., University of Louisville, 2008 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 Dissertation Approved on November 22, 2016 by the following Dissertation Committee: Dr. -

The District Messenger

THE DISTRICT MESSENGER The Newsletter of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE no. 156 4th December 1995 Sir Robert Stephens died on the 12th November. We who treasure that wonderful idiosyncratic film The Private Life of SherlockSherlock Holmes were put in our place by the obituaries, all of which dismissed it as a resounding flop. Stephens flourished mainly in the theatre, and he did actually play Sherlock Holmes on stage, in Toronto in 1976, in the RSC production of William Gillette's play. Like his friend Jeremy Brett, he really hit his stride in the last ten years of his life, especially as Falstaff and Lear. He was knighted last January. Lady Stephens was among the many friends and family who attended Jeremy Brett's memorial service last Wednesday at St Martin-in-the-Fields. The Sherlock Holmes Society of London, the Northern Musgraves, the BSI, the ASH, the Arthur Conan Doyle Society, the Société Sherlock Holmes de France, the Poor Folk Upon The Moors, and other groups were represented at the service, which was organised by Granada Television. Reports appeared in The Times and the Daily Telegraph the next day. Philip Attwell notes that plans to broadcast a tribute to Brett have been dropped, though BBC TV showed The Private Life last night in tribute to Robert Stephens. (*Last week's late film was the Hammer Hound of the BaskervillesBaskervilles; the Radio Times claimed that "Holmes scholars" regard it as the definitive version! I'd suggest that the BBC's own 1968 production, with Peter Cushing and Nigel Stock, more nearly fits that description. -

Sherlock Holmes and the Nazis: Fifth Columnists and the People’S War in Anglo-American Cinema, 1942-1943

Sherlock Holmes and the Nazis: Fifth Columnists and the People’s War in Anglo-American Cinema, 1942-1943 Smith, C Author post-print (accepted) deposited by Coventry University’s Repository Original citation & hyperlink: Smith, C 2018, 'Sherlock Holmes and the Nazis: Fifth Columnists and the People’s War in Anglo-American Cinema, 1942-1943' Journal of British Cinema and Television, vol 15, no. 3, pp. 308-327. https://dx.doi.org/10.3366/jbctv.2018.0425 DOI 10.3366/jbctv.2018.0425 ISSN 1743-4521 ESSN 1755-1714 Publisher: Edinburgh University Press This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Edinburgh University Press in Journal of British Cinema and Television. The Version of Record is available online at: http://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.3366/jbctv.2018.0425. Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. This document is the author’s post-print version, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer-review process. Some differences between the published version and this version may remain and you are advised to consult the published version if you wish to cite from it. Sherlock Holmes and the Nazis: Fifth Columnists and the People’s War in Anglo-American Cinema, 1942-1943 Christopher Smith This article has been accepted for publication in the Journal of British Film and Television, 15(3), 2018. -

It's a Kind of Magic: Situating Nostalgia for Technological Progress and The

IT’S A KIND OF MAGIC IT’S A KIND OF MAGIC: SITUATING NOSTALGIA FOR TECHNOLOGICAL PROGRESS AND THE OCCULT IN GUY RITCHIE’S SHERLOCK HOLMES MARKUS REISENLEITNER | YORK UNIVERSITY Guy Ritchie’s recent blockbuster success Le succès récent du blockbuster de Guy with a revisionist Sherlock Holmes is Ritchie revisitant la figure de Sherlock the latest in a series of popular films and Holmes s’inscrit dans une lignée récente fiction to have reinvigorated a nostalgic de films et de récits populaires qui ont imaginary of London’s past that places revivifié un imaginaire nostalgique du the former capital of the Empire at the passé londonien dans lequel le centre de crossroads of a persistent Manichean l’ancien empire britannique se trouve au battle between empiricist-driven croisement d’un conflit manichéen entre technological progress and traditions of un progrès scientifico-technologique occult knowledge supposedly submerged et les traditions d’un savoir occulte in the 17th century yet continuing to supposément enfouis dans les siècles trickle into the heart of the Empire précédents mais qui continue à s’insinuer from its colonies. By tracing some au cœur de l’empire à partir de ses of these historical layers sedimented colonies. En retraçant certaines de ces into 21st-century popular imaginaries couches historiques dans les recréations of London’s past, this paper explores contemporaines du Londres impérial, the mechanisms of popular culture’s cet article explore les mécanismes de production of nostalgia that mediate production de la nostalgie dans la culture public memories and histories and suture populaire en tant qu’ils font le pont them to the imaginary urban geographies entre la mémoire publique et la mémoire that constitute the space of the global historique en rattachant celles-ci à un city through its metonymic sites and its imaginaire de la géographie urbaine qui materialized histories. -

The Mysterious Moor

The Hound of the Baskervilles The Mysterious Moor The Lure of the Moor We often think of the English countryside as a pleasant land of forest and pasture, curbed by neat hedgerows and orderly gardens. But at higher elevations, a wilder landscape rears its head: the moor. Little thrives in any moor’s windy, rainy climate, leaving a rolling expanse of infertile wetlands dominated by tenacious gorse and grasses. Its harsh, chaotic weather, so inhospitable to human life, has nonetheless proved fertile ground for the many writers who’ve set their stories on its gloomy plain. A native of nearby Dorchester, Thomas Hardy set The Return of the Native, Tess of the D’Urbervilles, and other novels on the wild, haunted moor that D.H. Lawrence called “the real stuff of tragedy.” In Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, the violent, passionate Catherine and Heathcliff seem to echo the moors that surround them. Dame Agatha Christie booked herself into the “large, dreary” Moorland Hotel to finish work on The Mysterious Affair at Styles, while Dartmoor is the setting for The Sittaford Mystery (1931). The moor’s atmospheric weather and desolate landscape lend an air of tragedy and mystery to all of these tales, as they do to The Hound of the Baskervilles. On Dartmoor’s windswept plain, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle found the legendary roots and the creepy backdrop of his most famous story. He took many liberties, changing the names of geographic localities and altering distances to suit his story, but even today, Sherlock Holmes fans are known to set out across the moor in search of the real counterparts of the fictional locale where the story took place. -

Sherlock's Relationships in the Twenty-First Century

1 Sherlock's Relationships in the Twenty-First Century BA Thesis Stijn Koster 3653099 Gageldijk 84b 3566 MG Utrecht English Language and Culture dr. Roselinde Supheert 29 June 2014 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1: Adaptations 4 Chapter 2: Who is Sherlock? 6 Chapter 3: The Relationship Between Holmes and Watson 10 Chapter 4: Sherlock and the Others 15 4.1 Mycroft Holmes 16 4.2 Jim Moriarty 18 4.3 Gregory Lestrade / Scotland Yard 20 4.4 Mary Morstan 21 4.5 Irene Adler 23 4.6 Molly Hooper 23 4.7 A Conclusion to the Characters 25 Conclusion 26 Bibliography 27 3 Introduction There are very few people who have never heard of Sherlock Holmes. That is not because everyone has read Arthur Conan Doyle's stories about this famous character. Ever since the stories were first published in 1887 they have been adapted into screen films and television series. During these 100 years the character has also transformed. Newer adaptations have also been inspired by previous adaptations, which changes the Holmes that was first created by Conan Doyle into a character that the everyone who adapts him contributes to. Film adaptations are a filmmaker's interpretations of stories and characters. In recent years several Sherlock Holmes adaptations have been created. Many alterations regarding the original stories by Doyle have been made to please the contemporary audience. Due to limited time and space, this thesis shall focus mainly on the BBC series Sherlock created by Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat, which first aired in 2010. Gatiss and Moffat have analysed the characters and stories thoroughly; they have then deconstructed them en reassembled them in twenty-first century England. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62