The View from Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Fire Siege 2007 an Overview Cover Photos from Top Clockwise: the Santiago Fire Threatens a Development on October 23, 2007

CALIFORNIA FIRE SIEGE 2007 AN OVERVIEW Cover photos from top clockwise: The Santiago Fire threatens a development on October 23, 2007. (Photo credit: Scott Vickers, istockphoto) Image of Harris Fire taken from Ikhana unmanned aircraft on October 24, 2007. (Photo credit: NASA/U.S. Forest Service) A firefighter tries in vain to cool the flames of a wind-whipped blaze. (Photo credit: Dan Elliot) The American Red Cross acted quickly to establish evacuation centers during the siege. (Photo credit: American Red Cross) Opposite Page: Painting of Harris Fire by Kate Dore, based on photo by Wes Schultz. 2 Introductory Statement In October of 2007, a series of large wildfires ignited and burned hundreds of thousands of acres in Southern California. The fires displaced nearly one million residents, destroyed thousands of homes, and sadly took the lives of 10 people. Shortly after the fire siege began, a team was commissioned by CAL FIRE, the U.S. Forest Service and OES to gather data and measure the response from the numerous fire agencies involved. This report is the result of the team’s efforts and is based upon the best available information and all known facts that have been accumulated. In addition to outlining the fire conditions leading up to the 2007 siege, this report presents statistics —including availability of firefighting resources, acreage engaged, and weather conditions—alongside the strategies that were employed by fire commanders to create a complete day-by-day account of the firefighting effort. The ability to protect the lives, property, and natural resources of the residents of California is contingent upon the strength of cooperation and coordination among federal, state and local firefighting agencies. -

President Biden Appeals for Unity He Faces a Confluence of Crises Stemming from Pandemic, Insurrection & Race by BRIAN A

V26, N21 Thursday, Jan.21, 2021 President Biden appeals for unity He faces a confluence of crises stemming from pandemic, insurrection & race By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS – In what remains a crime scene from the insurrection on Jan. 6, President Joe Biden took the oath of office at the U.S. Capitol Wednesday, appealing to all Americans for “unity” and the survival of the planet’s oldest democ- racy. “We’ve learned again that democracy is precious,” when he declared in strongman fashion, “I alone can fix Biden said shortly before noon Wednesday after taking the it.” oath of office from Chief Justice John Roberts. “Democ- When Trump fitfully turned the reins over to Biden racy is fragile. And at this hour, my friends, democracy has without ever acknowledging the latter’s victory, it came prevailed.” after the Capitol insurrection on Jan. 6 that Senate Minor- His words of assurance came four years to the day ity Leader Mitch McConnell said he had “provoked,” leading since President Trump delivered his dystopian “American to an unprecedented second impeachment. It came with carnage” address, coming on the heels of his Republican National Convention speech in Cleveland in July 2016 Continued on page 3 Biden’s critical challenge By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS – Here is the most critical chal- lenge facing President Biden: Vaccinate as many of the 320 million Americans as soon as possible. While the Trump administration’s Operation Warp “Hoosiers have risen to meet Speed helped develop the CO- VID-19 vaccine in record time, these unprecedented challenges. most of the manufactured doses haven’t been injected into the The state of our state is resilient arms of Americans. -

Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 11 Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference by Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Transatlantic Security Studies, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Kathleen Bailey presents evidence of forgeries to the press corps. Credit: The Washington Times Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference Deception, Disinformation, and Strategic Communications: How One Interagency Group Made a Major Difference By Fletcher Schoen and Christopher J. Lamb Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 11 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2012 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Cartoon Animals Vs. Actual Russians: Russian Television and the Dynamics of Global Cultural Exchange 2021

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Jeffrey Brassard Cartoon Animals vs. Actual Russians: Russian Television and the Dynamics of Global Cultural Exchange 2021 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/16243 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Brassard, Jeffrey: Cartoon Animals vs. Actual Russians: Russian Television and the Dynamics of Global Cultural Exchange. In: VIEW. Journal of European Television History and Culture, Jg. 10 (2021), Nr. 19, S. 4– 15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/16243. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.18146/view.252 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0/ Attribution - Share Alike 4.0/ License. For more information see: Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ volume 10 issue 19/2021 CARTOON ANIMALS VS. ACTUAL RUSSIANS RUSSIAN TELEVISION AND THE DYNAMICS OF GLOBAL CULTURAL EXCHANGE Jeffrey Brassard University of Alberta [email protected] Abstract: Despite continual improvements in production and writing quality, live-action Russian series have fared poorly in the global market. While many deals have been struck, Western remakes of Russian series have failed to appear, and live-action programs have failed to find mainstream audiences outside of Russia. Russian animated series, on the other hand, have enjoyed global success. The success and failure of different types of Russian series in the global media market suggests that many of the central problems of cultural exchange remain. -

FHFD Newsletter Summer 2009

Newsletter Volume 11, Issue 1 August 2009 www.fhfd.org FIRE COMPANY PRESIDENT FIRE DEPARTMENT CHIEF FIRST AID CAPTAIN Jim Butler III Shaun Foley Brian O’Reilly FIRE POLICE CAPTAIN WATER RESCUE CAPTAIN AUXILIARY PRESIDENT Gene Stefanelli John P. Felsmann Dale Connor It’s Fair Time! The 2009 Fireman’s Fair opens this week! Friday, August 28 --- Saturday, September 5 The fun starts at 6:00 pm every night. - The Fair will be closed Sunday - HELP WANTED: The Fair Haven Fireman’s Fair is the Would you like to be part of the fun? longest running Fair in New Jersey! There’s still time to sign up to volunteer for Don’t miss out on these traditions: one or more nights! Where would you • Homemade clam chowder at the Firehouse Sea- like to work? food Restaurant (Doors open at 6:00 pm) Game Booths • Food Prep and Set Up • Wednesday is Family Night! One less ticket gets Waitresses you on a ride! Restaurant Hosts • Outback Snack Bar • Super 50/50 Drawing is Saturday night, Septem- ber 5th! Last year’s winner won over $20,000! • Sign up today at: www.fhfd.org • First Aid Squad Raffle: A SONY 40” Or LCD HDTV Flat Screen TV! Stop by the • Personnel Booth any • Many rides and game booths for kids of all ages! night Old favorites such as the Rainbow Ride, the Zipper of the Fair and sign and the Ferris Wheel...plus some surprises! Have you up with Joe or Rich. noticed the new Teacup Ride? - 1 - WATER, WATER, EVERYWHERE! FAIR HAVEN FIRE DEPARTMENT n June 13th, the Fair Haven Fire Depart- O ment hosted its first wetdown in over 15 years. -

Gm Police Fire & Crime Panel Supplementary Agenda Pdf 10 Mb

Public Document GREATER MANCHESTER POLICE, FIRE AND CRIME PANEL DATE: Friday, 14th May, 2021 TIME: 10.00 am VENUE: Manchester City Council, Council Chamber, Town Hall Extension, Albert Square, Manchester M60 2LA SUPPLEMENTARY AGENDA 6. CONFIRMATION OF THE APPOINTMENT OF DEPUTY MAYOR 1 – 12 7. GMF&RS FIRE PLAN 13 - 96 For copies of papers and further information on this meeting please refer to the website www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk. Alternatively, contact the following Governance & Scrutiny Officer: Steve Annette [email protected] This agenda was issued on 11 May 2021 on behalf of Julie Connor, Secretary to the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, Broadhurst House, 56 Oxford Street, Manchester M1 6EU BOLTON MANCHESTER ROCHDALE STOCKPORT TRAFFORD BURY OLDHAM SALFORD TAMESIDE WIGAN Please note that this meeting will be livestreamed via www.greatermanchester-ca.gov.uk, please speak to a Governance Officer before the meeting should you not wish to consent to being included in this recording. This page is intentionally left blank Agenda Item 6 GREATER MANCHESTER POLICE, FIRE AND CRIME PANEL Date: Friday 14th May 2021 Subject: Appointment of a Deputy Mayor for Policing and Crime Report of: Andy Burnham – Mayor of Greater Manchester PURPOSE OF REPORT The Mayor has decided to appoint a Deputy Mayor for Policing and Crime and in accordance with schedule 1 paragraph 9 of the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act 2011 the Police, Fire and Crime Panel must hold a confirmation hearing. This report sets out the procedures to be followed, the candidate’s qualifications in respect of the role and terms of employment. -

Lagrange Fire Department Annual Report '19 Lagrange Fire Department Fire Lagrange Lagrange Fire Department Table of Contents

LAGRANGE FIRE DEPARTMENT ANNUAL REPORT '19 LAGRANGE FIRE DEPARTMENT LAGRANGE FIRE DEPARTMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Message from Chief Brant 3 OVERVIEW LFD At a Glance 4 LFD Organizational Chart 6 LFD Zone Response Map 7 DIVISIONS Operations 8 Training 10 Prevention 11 Maintenance and Apparatus 12 Public Education 14 Accreditation 15 Special Projects 16 ACHIEVEMENTS 18 NEW HIRES/PROMOTIONS/RETIREMENTS 20 2 LAGRANGE FIRE DEPARTMENT MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF John Brant 2019 proved to be a very successful year for LaGrange Fire Department. We had many accomplishments and should be proud of our growth. We took a department that was in a good place and made it extraordinary. We continue to be an example for other departments to follow. As I have said it’s easy to be great once but the real challenge is being great all the time. We must, as an organization, keep our foot on the pedal and continue to grow and develop our people and our organization. Our goal at the LaGrange Fire Department is to continuously exceed the expectations of the community and our stakeholders. In 2019 we reached three major milestones. We added a fifth fire station that will provide quicker response to the northwest quadrant of the city. We added a training center that meets all our training needs. We maintained our ISO classification of 2 during our last audit. To have these two additions to our department within a single year is exceptional and to maintain our ISO classification was monumental. Each of these milestones helps us provide a better service for the citizens of LaGrange. -

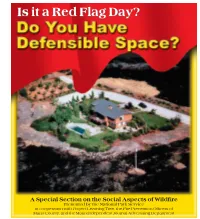

Is It a Red Flag Day?

Is it a Red Flag Day? A Special Section on the Social Aspects of Wildfire Presented by the National Park Service in cooperation with Project Learning Tree, the Fire Prevention Officers of Marin County, and the Marin Independent Journal Advertising Department 2 Fire Recycles ildland fire is an plant particles while the larger material AIR SUN W ecological remains as ash. process affecting almost Ash returns nutrients from plants back all of the earth's vegeta- into the soil, especially calcium, potassi- tion. Underwater plants um and phosphorous. Nitrogen is are generally an returned by the nitrogen-fixing plants that PLANTS excpetion, although flourish after a fire and begin the process FIRE when seaweed or algae of regrowth. Without nitrogen, proteins are left onshore to dry, cannot be made, and DNA cannot be SOIL they too, can become fuel. reproduced. In some places, wildland fire occurs regularly enough that Most of the earth's nitrogen is in the species depend on it. air, but can’t be breathed in. Nitrogen-fix- What's Inside ers host bacteria in their roots which The length of a fire return interval, or convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form Fire Recycles . 2 "fire cycle" varies based on the climate, plants and animals can use. Defensible Space vegetation, and ignition frequency of a Like many hardwood trees, shrubs and other Perspectives. 3 particular location. Ignitions are mainly Plants in the pea family (legumes) are flowering plants, this California bay survived caused by lightning, volcanic ash, lava, notorious for their nitrogen fixing abilities. a wildfire by resprouting at the base. -

Mccarthyism and the Big Lie

University of Central Florida STARS PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements 1-1-1953 McCarthyism and the big lie Milton Howard Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Book is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Howard, Milton, "McCarthyism and the big lie" (1953). PRISM: Political & Rights Issues & Social Movements. 45. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/prism/45 and the BIG LIE McCARTHYISM AND THE BIG LIE By MILTON HOWARD A man is standing on the steps of the US. Trsssnry Buildiig in downtown New York. He irs &outing his contempt for any American who believes we can have peace in tbis world. He says such Americas are "Kremlin dupes." He derides them as "egg-heads and appeaser&" The speaker is Joe McCarthy, U.S. Senator from Wisconsin. He holds the crowd's attention. He has studied the trade of lashing hysteria into rm audience. Five years ago, he was a little known pvliti- . cian. Today, his name has become known throughout the world. .Hehas baptized the poIitical fact known as McCarthykn. Americans began to get a whiff of this new fact when millions eud- denly faced what is now known as "The Reign of Fear." Three years ago, the President of the U.S.A. startled the world. He said that the American citizens of the state of Wisconsin were afraia. -

Marx and Mendacity: Can There Be a Politics Without Hypocrisy?

Analyse & Kritik 01+02/2015 (© Lucius & Lucius, Stuttgart) S. 521 Martin Jay Marx and Mendacity: Can There Be a Politics without Hypocrisy? Abstract: As demonstrated by Marx's erce defence of his integrity when anonymously accused of lying in l872, he was a principled believer in both personal honesty and the value of truth in politics. Whether understood as enabling an accurate, `scientic' depiction of the contradictions of the present society or a normative image of a truly just society to come, truth-telling was privileged by Marx over hypocrisy as a political virtue. Contemporary Marxists like Alain Badiou continue this tradition, arguing that revolutionary politics should be understood as a `truth procedure'. Drawing on the alternative position of political theorists such as Hannah Arendt, who distrusted the monologic and absolutist implications of a strong notion of truth in politics, this paper defends the role that hypocrisy and mendacity, understood in terms of lots of little lies rather than one big one, can play in a pluralist politics, in which, pace Marx, rhetoric, opinion and the clash of values resist being subsumed under a singular notion of the truth. 1. Introduction In l872, an anonymous attack was launched in the Berlin Concordia: Zeitschrift für die Arbeiterfrage against Karl Marx for having allegedly falsied a quotation from an 1863 parliamentary speech by the British Liberal politician, and future Prime Minister, William Gladstone in his own Inaugural Address to the First International in l864. The polemic was written, so it was later disclosed, by the eminent liberal political economist Lujo Brentano.1 Marx vigorously defended himself in a response published later that year in Der Volksstaat, launching a bitter debate that would drag on for two decades, involving Marx's daughter Eleanor, an obscure Cambridge don named Sedly Taylor, and even Gladstone himself, who backed Brentano's version. -

Is Castro's Cuba a Budding Narcostate?

Vol. 20, No. 4 April 2012 In the News Despite fall in U.S. food exports to Cuba, Advertising everywhere shipments of beans edge up every year Competition heats up in Cuba’s rapidly BY VITO ECHEVARRÍA It was also the same year Pat Wallesen visited decentralizing economy ................Page 3 he Cubans haven’t bought a single grain Cuba for the first time. Wallesen is managing of American rice for years. But when it partner of WestStar Food Co. in Corpus Christi, Tcomes to U.S. beans, state purchasing a major U.S. exporter of dry beans. SEC pressures Telefónica agency Alimport can’t seem to get enough. “The Cubans are opportunistic buyers,” said Spanish telecom giant is hounded over its According to USDA figures, dry bean exports Wallesen, telling CubaNews that global commo- business interests in Cuba ............Page 4 to Cuba reached $7.7 million last year, up from dity prices have fluctuated not only for beans lately, but other crops as well. He put total annu- $5.6 million in 2010 and $4.3 million in 2009. al dry bean purchases at 45,000 metric tons. Political briefs That’s still a lot less than the record $10.9 mil- “They buy when the time is right. They buy lion worth of beans sold in 2006, though dra- from the U.S. between November and Febru- Rubio lifts hold on Jacobson nomination; matically more than in 2007 and 2008, when U.S. Miami-Dade proposal under fire ...Page 5 ary,” he said. WestStar Foods sometimes sup- farmers exported only $73,000 and $68,000 plies the Cubans with its own inventory of worth of beans to Cuba (see chart, page 3). -

ENDER's GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third

ENDER'S GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third "I've watched through his eyes, I've listened through his ears, and tell you he's the one. Or at least as close as we're going to get." "That's what you said about the brother." "The brother tested out impossible. For other reasons. Nothing to do with his ability." "Same with the sister. And there are doubts about him. He's too malleable. Too willing to submerge himself in someone else's will." "Not if the other person is his enemy." "So what do we do? Surround him with enemies all the time?" "If we have to." "I thought you said you liked this kid." "If the buggers get him, they'll make me look like his favorite uncle." "All right. We're saving the world, after all. Take him." *** The monitor lady smiled very nicely and tousled his hair and said, "Andrew, I suppose by now you're just absolutely sick of having that horrid monitor. Well, I have good news for you. That monitor is going to come out today. We're going to just take it right out, and it won't hurt a bit." Ender nodded. It was a lie, of course, that it wouldn't hurt a bit. But since adults always said it when it was going to hurt, he could count on that statement as an accurate prediction of the future. Sometimes lies were more dependable than the truth. "So if you'll just come over here, Andrew, just sit right up here on the examining table.