The Classification of Verbs in English Some Criteria the Classification of Verbs in English Some Criteria Asst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ditransitive Verbs in Language Use

Chapter 3 Aspects of description: ditransitive verbs in language use This chapter provides a corpus-based description of individual ditransitive verbs in actual language use. First, the two verbs that are typical of ditransitivity in ICE-GB will be analysed: give and tell (see section 3.1). Second, the four habitual ditransitive verbs in ICE-GB (i.e. ask, show, send and offer) will be scrutinised (see section 3.2). Particular emphasis in all the analyses will be placed on the different kinds of routines that are involved in the use of ditransitive verbs. The description of peripheral ditransitive verbs, on the other hand, will centre on the concepts of grammatical institutionalisation and conventionalisation (see section 3.3). At the end of this chapter, the two aspects will be discussed in a wider setting in the assessment of the role of linguistic routine and creativity in the use of ditransitive verbs (see section 3.4). 3.1 Typical ditransitive verbs in ICE-GB In the present study, typical ditransitive verbs are verbs which are frequently attested in ICE-GB in general (i.e. > 700 occurrences) and which are associated with an explicit ditransitive syntax in some 50% of all occurrences or more (cf. Figure 2.4, p. 84). These standards are met by give (see section 3.1.1) and tell (see section 3.1.2). 3.1.1 GIVE In light of recent psycholinguistic and cognitive-linguistic evidence, it is not sur- prising that the most frequent ditransitive verb in ICE-GB is GIVE.1 Experiment- al data have led Ninio (1999), for example, to put forward the hypothesis that children initially acquire constructions through one (or very few) ‘pathbreaking verbs(s)’. -

Deixis and Reference Tracing in Tsova-Tush (PDF)

DEIXIS AND REFERENCE TRACKING IN TSOVA-TUSH A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2020 by Bryn Hauk Dissertation committee: Andrea Berez-Kroeker, Chairperson Alice C. Harris Bradley McDonnell James N. Collins Ashley Maynard Acknowledgments I should not have been able to finish this dissertation. In the course of my graduate studies, enough obstacles have sprung up in my path that the odds would have predicted something other than a successful completion of my degree. The fact that I made it to this point is a testament to thekind, supportive, wise, and generous people who have picked me up and dusted me off after every pothole. Forgive me: these thank-yous are going to get very sappy. First and foremost, I would like to thank my Tsova-Tush host family—Rezo Orbetishvili, Nisa Baxtarishvili, and of course Tamar and Lasha—for letting me join your family every summer forthe past four years. Your time, your patience, your expertise, your hospitality, your sense of humor, your lovingly prepared meals and generously poured wine—these were the building blocks that supported all of my research whims. My sincerest gratitude also goes to Dantes Echishvili, Revaz Shankishvili, and to all my hosts and friends in Zemo Alvani. It is possible to translate ‘thank you’ as მადელ შუნ, but you have taught me that gratitude is better expressed with actions than with set phrases, sofor now I will just say, ღაზიშ ხილჰათ, ბედნიერ ხილჰათ, მარშმაკიშ ხილჰათ.. -

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-Linguistic Paerns and Variation

A Minimalist Study of Complex Verb Formation: Cross-linguistic Paerns and Variation Chenchen Julio Song, [email protected] PhD First Year Report, June 2016 Abstract is report investigates the cross-linguistic paerns and structural variation in com- plex verbs within a Minimalist and Distributed Morphology framework. Based on data from English, German, Hungarian, Chinese, and Japanese, three general mechanisms are proposed for complex verb formation, including Akt-licensing, “two-peaked” adjunction, and trans-workspace recategorization. e interaction of these mechanisms yields three levels of complex verb formation, i.e. Root level, verbalizer level, and beyond verbalizer level. In particular, the verbalizer (together with its Akt extension) is identified as the boundary between the word-internal and word-external domains of complex verbs. With these techniques, a unified analysis for the cohesion level, separability, component cate- gory, and semantic nature of complex verbs is tentatively presented. 1 Introduction1 Complex verbs may be complex in form or meaning (or both). For example, break (an Accom- plishment verb) is simple in form but complex in meaning (with two subevents), understand (a Stative verb) is complex in form but simple in meaning, and get up is complex in both form and meaning. is report is primarily based on formal complexity2 but tries to fit meaning into the picture as well. Complex verbs are cross-linguistically common. e above-mentioned understand and get up represent just two types: prefixed verb and phrasal verb. ere are still other types of complex verb, such as compound verb (e.g. stir-fry). ese are just descriptive terms, which I use for expository convenience. -

Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4802–4810 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Much Ado About Nothing Identification of Zero Copulas in Hungarian Using an NMT Model Andrea Dömötör1;2, Zijian Gyoz˝ o˝ Yang1, Attila Novák1 1MTA-PPKE Hungarian Language Technology Research Group, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Information Technology and Bionics Práter u. 50/a, 1083 Budapest, Hungary 2Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Egyetem u. 1, 2087 Piliscsaba, Hungary {surname.firstname}@itk.ppke.hu Abstract The research presented in this paper concerns zero copulas in Hungarian, i.e. the phenomenon that nominal predicates lack an explicit verbal copula in the default present tense 3rd person indicative case. We created a tool based on the state-of-the-art transformer architecture implemented in Marian NMT framework that can identify and mark the location of zero copulas, i.e. the position where an overt copula would appear in the non-default cases. Our primary aim was to support quantitative corpus-based linguistic research by creating a tool that can be used to compile a corpus of significant size containing examples of nominal predicates including the location of the zero copulas. We created the training corpus for our system transforming sentences containing overt copulas into ones containing zero copula labels. However, we first needed to disambiguate occurrences of the massively ambiguous verb van ‘exist/be/have’. We performed this using a rule-base classifier relying on English translations in the English-Hungarian parallel subcorpus of the OpenSubtitles corpus. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Flexible Valency in Chintang.∗

Flexible valency in Chintang.∗ Robert Schikowskia , Netra Paudyalb , and Balthasar Bickela a University of Zürich b University of Leipzig 1 e Chintang language Chintang [ˈts̻ ʰiɳʈaŋ]̻ (ISO639.3: ctn) is a Sino-Tibetan language of Nepal. It is named aer the village where it is mainly spoken. e village lies in the hills of Eastern Nepal, bigger cities within day’s reach being Dhankuṭā and Dharān. ere are no official data on the number of speakers, but we estimate there to be around 4,000 - 5,000 speakers. Most speakers are bi- or trilingual, with Nepali (the Indo-Aryan lingua franca of Nepal) as one and Bantawa (a related Sino-Tibetan language) as the other additional language. Monolingual speakers are still to be found mainly among elderly women, whereas a considerable portion of the younger generation is rapidly shiing to Nepali. Genealogically, Chintang belongs to the Kiranti group. e Kiranti languages are generally accepted to belong to the large Sino-Tibetan (or Tibeto-Burman) family, although their position within this family is controversial (cf. e.g. urgood 2003, Ebert 2003). Based on phonological evidence, Chintang belongs to the Eastern subgroup of Kiranti (Bickel et al. 2010). ere are two major dialects (Mulgaũ and Sambugaũ ) named aer the areas where they are spoken. e differences between them concern morphology and the lexicon but, as far as we know, not syntax, and so we will not distinguish between dialects in this chapter. For all examples the source has been marked behind the translation. Wherever possible, we take data from the Chintang Language Corpus (Bickel et al. -

A Study on English Collocations and Delexical Verbs in English Curriculum

Pramana Research Journal ISSN NO: 2249-2976 CORPUS-BASED LINGUISTIC AND INSTRUCTIVE ANALYSIS: A STUDY ON ENGLISH COLLOCATIONS AND DELEXICAL VERBS IN ENGLISH CURRICULUM Dr. G. Shravan Kumar, Dr. Gomatam Mohana Charyulu Professor of English & Head, Associate Professor of English Controller of Examinations, VFSTR Deemed to be University PJTS Agricultural University, Vadlamudi, A.P. India Rajendranagar, Hyderabad. TS Abstract: The influence of native language on the learners of the English language is not a new issue. Moreover, expressions of colloquial native expressions into English language are also common in English speaking people in India. Introducing English Collocations into the curriculum through practice exercises at the end of the lessons at primary and secondary level is a general practice of curriculums designers to improve the skills of language learners. There is a vast scope of research on the English collocations in lessons introduced to learners at the initial stages in Telugu speakers of native India. In fact, it is a neglected area of investigation that knowledge of collocation can also improve the language competency. This paper investigates the English collocations and delexical verbs used by English learners. In order to make a perfect investigative study on the topic, this attempt was undertaken two groups of rural Ranga Reddy District of Telangana State English learners of different proficiencies who belonged to 8,9 and 10th class levels. This investigation proved that the English learners of the Rural Students in Telangana depended on three major important things. They are 1. Native language Transfer 2. Synonymy 3. Over generalization. This study also showed that the high and low proficiency learners were almost familiar with collocations and delexical verbs. -

6 the Major Parts of Speech

6 The Major Parts of Speech KEY CONCEPTS Parts of Speech Major Parts of Speech Nouns Verbs Adjectives Adverbs Appendix: prototypes INTRODUCTION In every language we find groups of words that share grammatical charac- teristics. These groups are called “parts of speech,” and we examine them in this chapter and the next. Though many writers onlanguage refer to “the eight parts of speech” (e.g., Weaver 1996: 254), the actual number of parts of speech we need to recognize in a language is determined by how fine- grained our analysis of the language is—the more fine-grained, the greater the number of parts of speech that will be distinguished. In this book we distinguish nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs (the major parts of speech), and pronouns, wh-words, articles, auxiliary verbs, prepositions, intensifiers, conjunctions, and particles (the minor parts of speech). Every literate person needs at least a minimal understanding of parts of speech in order to be able to use such commonplace items as diction- aries and thesauruses, which classify words according to their parts (and sub-parts) of speech. For example, the American Heritage Dictionary (4th edition, p. xxxi) distinguishes adjectives, adverbs, conjunctions, definite ar- ticles, indefinite articles, interjections, nouns, prepositions, pronouns, and verbs. It also distinguishes transitive, intransitive, and auxiliary verbs. Writ- ers and writing teachers need to know about parts of speech in order to be able to use and teach about style manuals and school grammars. Regardless of their discipline, teachers need this information to be able to help students expand the contexts in which they can effectively communicate. -

Positional Verbs in Nen

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The Australian National University Positional Verbs in Nen Nicholas Evans AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY In this paper, I lay out the workings of the rather unusual system of positional verbs found in Nen, a language of the Morehead-Maro family in Morehead dis- trict, Western Province, Papua New Guinea. Nen is unusual in its lexicalization patterns: it has very few verbs that are intransitive, with most verbs that tend to be intransitive cross-linguistically realized as morphologically middle verbs, including ‘talk’, ‘work’, ‘descend’, and so on. Within the fifty attested morpho- logically intransitive verbs, forty-five comprise an interesting class of “positional verbs,” the subject of this paper; the others are ‘be’, its derivatives ‘come’ and ‘go’ (lit. ‘be hither’ and ‘be thither’), and ‘walk’. Positional verbs denote spatial positions and postures like ‘be sitting’, ‘be up high’, ‘be erected (of a building)’, ‘be open’, ‘be in a tree-fork’, ‘be at the end of something’. Positional verbs differ from regular verbs in lacking in¿nitives, in possessing a special “stative” aspect inÀection and an unusual system for building a four- way number system (building large plurals by combining singular and dual markers), and in participating in a productive three-way alternation between positional statives (like ‘be high’), placement transitives (like ‘put up high’), and get-into-position middles (like ‘get into a high position’). The latter two types are more like normal verbs (for example, they possess in¿nitives and participate in the normal TAM series), but they are formally derived from the positionals. -

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

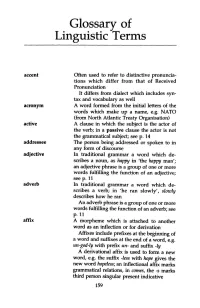

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

Verbs in Relation to Verb Complementation 11-69

1168 Complementation of verbs and adjectives Verbs in relation to verb complementation 11-69 They may be either copular (clause pattern SVC), or complex transitive verbs, or monotransitive verbs with a noun phrase object), we can give only (clause pattern SVOC): a sample of common verbs. In any case, it should be borne in mind that the list of verbs conforming to a given pattern is difficult to specífy exactly: there SVC: break even, plead guilty, Iie 101V are many differences between one variety of English and another in respect SVOC: cut N short, work N loose, rub N dry of individual verbs, and many cases of marginal acceptability. Sometimes the idiom contains additional elements, such as an infinitive (play hard to gel) or a preposition (ride roughshod over ...). Note The term 'valency' (or 'valencc') is sometimes used, instead of complementation, ror the way in (The 'N' aboye indicates a direct object in the case oftransitive examples.) which a verb determines the kinds and number of elements that can accompany it in the clause. Valency, however, incIudes the subject 01' the clause, which is excluded (unless extraposed) from (b) VERB-VERB COMBINATIONS complementation. In these idiomatic constructions (ef 3.49-51, 16.52), the second verb is nonfinite, and may be either an infinitive: Verbs in intransitive function 16.19 Where no eomplementation oecurs, the verb is said to have an INTRANSITIVE make do with, make (N) do, let (N) go, let (N) be use. Three types of verb may be mentioned in this category: or a participle, with or without a following preposition: (l) 'PURE' INTRANSITIVE VERas, which do not take an object at aH (or at put paid to, get rid oJ, have done with least do so only very rarely): leave N standing, send N paeking, knock N fiying, get going John has arrived. -

Verbs Show an Action (Eg to Run)

VERBS Verbs show an action (e.g. to run). The tricky part is that sometimes the action can't be seen on the outside (like run) – it is done on the inside (e.g. to decide). Sometimes the action even has to do with just existing, in other words to be (e.g. is, was, are, were, am). Tenses The three basic tenses are past, present and future. Past – has already happened Present – is happening Future – will happen To change a word to the past tense, add "-ed" (e.g. walk → walked). ***Watch out for the words that don't follow this (or any) rule (e.g. swim → swam) *** To change a word to the future tense, add "will" before the word (e.g. walk → will walk BUT not will walks) Exercise 1 For each word, write down the correct tense in the appropriate space in the table below. Past Present Future dance will plant looked runs shone will lose put dig Spelling note: when "-ed" is added to a word ending in "y", the "y" becomes an "i" e.g. try → tried These are the basic tenses. You can break present tense up into simple present (e.g. walk), present perfect (e.g. has walked) and present continuous (e.g. is walking). Both past and future tenses can also be broken up into simple, perfect and continuous. You do not need to know these categories, but be aware that each tense can be found in different forms. Is it a verb? Can it be acted out? no yes Can it change It's a verb! tense? no yes It's NOT a It's a verb! verb! Exercise 2 In groups, decide which of the words your teacher gives you are verbs using the above diagram.