Does Urbanization Influence the Diet of a Large Snake?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reptiles in and Around the House Identification and Distribution Reptiles Inhabit Every Environment in Australia

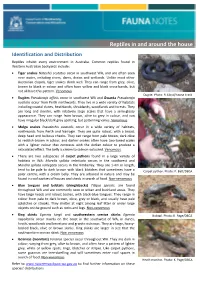

Reptiles in and around the house Identification and Distribution Reptiles inhabit every environment in Australia. Common reptiles found in Western Australian backyards include: Tiger snakes Notechis scutatus occur in southwest WA, and are often seen near water, including rivers, dams, drains and wetlands. Unlike most other Australian elapids, tiger snakes climb well. They can range from grey, olive, brown to black in colour and often have yellow and black cross-bands, but not all have this pattern. Venomous Dugite. Photo: R. Lloyd/Fauna Track Dugites Pseudonaja affinis occur in southwest WA and Gwarda Pseudonaja nuchalis occur from Perth northwards. They live in a wide variety of habitats including coastal dunes, heathlands, shrublands, woodlands and forests. They are long and slender, with relatively large scales that have a semi-glossy appearance. They can range from brown, olive to grey in colour, and can have irregular black/dark grey spotting, but patterning varies. Venomous Mulga snakes Pseudechis australis occur in a wide variety of habitats, northwards from Perth and Narrogin. They are quite robust, with a broad, deep head and bulbous cheeks. They can range from pale brown, dark olive to reddish-brown in colour, and darker snakes often have two-toned scales with a lighter colour that contrasts with the darker colour to produce a reticulated effect. The belly is cream to salmon-coloured. Venomous There are two subspecies of carpet pythons found in a large variety of habitats in WA: Morelia spilota imbricata occurs in the southwest and Morelia spilota variegata occurs in the Kimberley. They are 1-4m in length, tend to be pale to dark brown with black blotches that sometimes have a Carpet python. -

Venemous Snakes

WASAH WESTERN AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY of AMATEUR HERPETOLOGISTS (Inc) K E E P I N G A D V I C E S H E E T Venomous Snakes Southern Death Adder (Acanthophis Southern Death antarcticus) – Maximum length 100 cm. Adder Category 5. Desert Death Adder (Acanthophis pyrrhus) – Acanthophis antarcticus Maximum length 75 cm. Category 5. Pilbara Death Adder (Acanthophis wellsi) – Maximum length 70 cm. Category 5. Western Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) - Maximum length 160 cm. Category 5. Mulga Snake (Pseudechis australis) – Maximum length 300 cm. Category 5. Spotted Mulga Snake (Pseudechis butleri) – Maximum length 180 cm. Category 5. Dugite (Pseudonaja affinis affinis) – Maximum Desert Death Adder length 180 cm. Category 5. Acanthophis pyrrhus Gwardar (Pseudonaja nuchalis) – Maximum length 100 cm. Category 5. NOTE: All species listed here are dangerously venomous and are listed as Category 5. Only the experienced herpetoculturalist should consider keeping any of them. One must be over 18 years of age to hold a category 5 license. Maintaining a large elapid carries with 1 it a considerable responsibility. Unless you are Pilbara Death Adder confident that you can comply with all your obligations and licence requirements when Acanthophis wellsi keeping dangerous animals, then look to obtaining a non-venomous species instead. NATURAL HABITS: Venomous snakes occur in a wide variety of habitats and, apart from death adders, are highly mobile. All species are active day and night. HOUSING: In all species listed except death adders, one adult (to 150 cm total length) can be kept indoors in a lockable, top-ventilated, all glass or glass-fronted wooden vivarium of Western Tiger Snake at least 90 x 45 cm floor area. -

Taxonomy of the Genus Pseudonaja (Reptilia: Elapidae) in Australia

AUSTRALIAN BIODIVERSITY RECORD ________________________________________________________ 2002 (No 7) ISSN 1325-2992 March, 2002 ________________________________________________________ Taxonomy of the Genus Pseudonaja (Reptilia: Elapidae) in Australia. by Richard W. Wells “Shiralee”, Major West Road, Cowra, New South Wales, Australia The clear morphological differences that exist within the genus as previously considered strongly indicate that it is a polyphyletic assemblage. Accordingly, I have taken the step of formally proposing the fragmentation of Pseudonaja. In this work I have decided to restrict the genus Pseudonaja to the Pseudonaja nuchalis complex. Additionally, I herein formally resurrect from synonymy the generic name Euprepiosoma Fitzinger, 1860 for the textilis group of species, erect a new generic name (Placidaserpens gen. nov.) for the snakes previously regarded as Pseudonaja guttata, erect a new generic name (Notopseudonaja gen. nov.) for the group of species previously regarded as the Pseudonaja modesta complex, and erect a new generic name (Dugitophis gen. nov.) for snakes previously regarded as the Pseudonaja affinis complex. Genus Pseudonaja Gunther, 1858 The Pseudonaja nuchalis Complex It is usually reported that Pseudonaja nuchalis occurs across most of northern, central and western Australia, ranging from Cape York Peninsula, in the north-east, through western, southern and south-eastern Queensland, far western New South Wales, north-western Victoria, and most of South Australia, Northern Territory and Western Australia. However, this distribution pattern is now known to actually represents several different species all regarded by most authorities for convenience as the single highly variable species, 'Pseudonaja nuchalis'. As usually defined, this actually is a highly variable and therefore confusing group of species to identify and it is not all surprising that there has been difficulty in breaking up the group. -

Structure±Function Properties of Venom Components from Australian Elapids

PERGAMON Toxicon 37 (1999) 11±32 Review Structure±function properties of venom components from Australian elapids Bryan Grieg Fry * Peptide Laboratory, Centre for Drug Design and Development, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Qld, 4072, Australia Received 9 December 1997; accepted 4 March 1998 Abstract A comprehensive review of venom components isolated thus far from Australian elapids. Illustrated is that a tremendous structural homology exists among the components but this homology is not representative of the functional diversity. Further, the review illuminates the overlooked species and areas of research. # 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Australian elapids are well known to be the most toxic in the world, with all of the top ten and nineteen of the top 25 elapids with known LD50s residing exclusively on this continent (Broad et al., 1979). Thus far, three main types of venom components have been characterised from Australian elapids: prothrombin activating enzymes; lipases with a myriad of potent activities; and powerful peptidic neurotoxins. Many species have the prothrombin activating enzymes in their venoms, the vast majority contain phospholipase A2s and all Australian elapid venoms are suspected to contain peptidic neurotoxins. In addition to the profound neurological eects such as disorientation, ¯accid paralysis and respiratory failure, characteristic of bites by many species of Australian elapids is hemorrhaging and incoagulable blood. As a result, these elapids can be divided into two main classes: species with procoagulant venom (Table 1) and species with non-procoagulant venoms (Table 2) (Tan and * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. 0041-0101/98/$ - see front matter # 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd. -

Dugite Discovery SHY, SCALY PREDATOR Dugites Are Quite Common Around Perth and Are Most Likely to Be Seen During the Daytime in Warmer Months

ED!MAY 13, 2020 Dugite discovery SHY, SCALY PREDATOR Dugites are quite common around Perth and are most likely to be seen during the daytime in warmer months. They are one of the native species that have benefited from urbanisation, which has brought with it new food sources and places to shelter. Most snake bites that occur around Perth are from dugites. While they are generally shy, they will attack if they feel threatened. They are listed as the 13th most venomous snake in the world by the Australian Venom Research Unit. Turn to page 3 to find out more about this amazing reptile. EXPERIMENT WITH EGGS TO LEARN ABOUT TOOTH DECAY. P4 INE MAR t MEDIAs momen matter SCIENCE MIXED LAB BAG ure GET creat thy FEATURE heal ED! • 2 Maths & English Wednesday, May 13, 2020 MATHS IN minds NumbatFOCUS numbers EQUATIONS Race around the track to help the numbat find a feast of termites. Along the way, colourINE in all of the blocks that are equivalent to the magic numberMAR at the centre.t start MEDIA s mSTEMomen 1+4 4+4 2+1 3+0 everydaymatter Hint: There are 10 iny total, and they get harder the further you go. here ENGLISH pla Challenge yourself: q Try it without a calculator. q Set a time limit and try to beat it. q Try finishing quickly by estimating answers to see which are most 60÷10 15÷5 27-24 122-114 6+5 likely to be right. SCIENCE MIpXEDle & LAB peoBAGES FRACTIONPLAC ACTION Draw lines to match the fractions below to their equivalent values. -

Ontogenetic Shift in Diet of a Large Elapid Snake Is Facilitated by Allometric Change in Skull Morphology

Ontogenetic shift in diet of a large elapid snake is facilitated by allometric change in skull morphology Matthew Brenton Patterson ( [email protected] ) Murdoch University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4468-952X Ashleigh K Wolfe Curtin University Bentley Campus: Curtin University Patricia A Fleming Murdoch University South Street Campus: Murdoch University Philip W Bateman Curtin University Bentley Campus: Curtin University Meg Martin Murdoch University South Street Campus: Murdoch University Emma Sherratt The University of Adelaide Natalie M Warburton Murdoch University South Street Campus: Murdoch University Research Article Keywords: Trophic ·Squamata, Geometric morphometrics, Allometric scaling, Post-natal growth, Micro-CT Posted Date: September 1st, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-853742/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/30 Abstract As snakes are limbless, gape-limited predators, their skull is the main feeding structure involved in prey handling, manipulation and feeding. Ontogenetic changes in prey type and size are likely to be associated with distinct morphological changes in the skull during growth. We investigated ontogenetic variation in diet from stomach contents of n = 161 dugite specimens (Pseudonaja anis, Elapidae) representing the full range of body size for the species, and skull morphology of 46 specimens (range 0.25–1.64 m snout- vent-length; SVL). We hypothesised that changes in prey type throughout postnatal ontogeny would coincide with distinct changes in skull shape. Dugites demonstrate a distinct size-related shift in diet: the smallest individuals ate autotomised reptile tails, medium-sized individuals predominantly ate small reptiles (as snakes grew larger there was an increased likelihood of feeding on reptiles head-rst), and the largest individuals (> 0.8 m SVL) ate mammals and large reptiles. -

Everywhere and Nowhere

Landscapes: the Journal of the International Centre for Landscape and Language Volume 4 Issue 2 Sustainabilia Article 14 January 2011 Everywhere and Nowhere Liana Christensen Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/landscapes Part of the Photography Commons Recommended Citation Christensen, L. (2011). Everywhere and Nowhere. Landscapes: the Journal of the International Centre for Landscape and Language, 4(2). Retrieved from https://ro.ecu.edu.au/landscapes/vol4/iss2/14 This Article (non-refereed) is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/landscapes/vol4/iss2/14 Christensen: Everywhere and Nowhere Edith Cowan University School of Communications and Arts Centre for Research in Entertainment, Arts, Technology, Education & Communications The International Centre for Landscape and Language Landscapes ISSN 1448-0778 EVERYWHERE AND NOWHERE Liana Christensen In 1788 Europeans arrived here to stay. Since then, between eighteen and twenty mammal species have been lost, depending on who‘s counting. Gone, too, are the Paradise Parrot and the Dwarf Emu. Alarmingly high numbers of animal (and plant) species hover just this side of oblivion. Not infrequently in Australia‘s natural history the first sighting of an animal by a colonial collector is followed fairly swiftly by a long disappearance. Very few come back. For the most part, expanding populations of exotic predators and feral competitors, combined with shrinking islands of natural habitats mean that the average Australian has few chances to experience firsthand even the commonest creatures of this continent. These days, the closest many people come to direct contact with an indigenous mammal is via the roo bars on their oversized four-wheel-drive vehicles. -

Highly Classified Years 11-12

Highly Classified Years 11-12 Getting Sorted Locate the animals listed below and find out their scientific name. Remember that the scientific name is usually written in italics or is underlined. Common Name Scientific Name (Genus species) A. Javan Gibbon _____________________________________ B. Southern White Rhino _____________________________________ C. Asian Elephant _____________________________________ D. Western Swamp Tortoise _____________________________________ E. Dugite _____________________________________ F. Little Penguin _____________________________________ G. Sumatran Orangutan _____________________________________ H. African Painted Dog _____________________________________ I. Green Tree Frog _____________________________________ J. Nepalese Red Panda _____________________________________ K. Perentie _____________________________________ L. Southern Cassowary _____________________________________ Classify these animals according to the groupings in the tables below and the fol- lowing page (note: only use the LETTER corresponding to each animal, not the common or scientific name) Body Covering Moist Skin Dry Scales Wet Scales Feathers Fur/Hair Distribution Africa Asia Australia Highly Classified Years 11-12 Getting Sorted (continued) Diet (in the wild) Herbivore Carnivore Omnivore Habitat Terrestrial (land dwelling) Arboreal (tree living) Aquatic (water living) Vertebrate Class (only considering 5 basic groupings) Pisces (Fish) Amphibia Reptilia Mammalia Aves (Birds) Despite their similarities, ‘Fish’ are only an informal -

Fauna Assessment

Fauna Assessment South Capel May 2018 V4 On behalf of: Iluka Resources Limited 140 St Georges Terrace PERTH WA 6000 Prepared by: Greg Harewood Zoologist PO Box 755 BUNBURY WA 6231 M: 0402 141 197 E: [email protected] FAUNA ASSESSMENT – SOUTH CAPEL –– MAY 2018 – V4 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 2. SCOPE OF WORKS ................................................................................................ 1 3. METHODS ............................................................................................................... 2 3.1 POTENTIAL FAUNA INVENTORY - LITERATURE REVIEW ................................. 2 3.1.1 Database Searches ....................................................................................... 2 3.1.2 Previous Fauna Surveys in the Area ............................................................. 2 3.1.3 Fauna of Conservation Significance .............................................................. 4 3.1.4 Invertebrate Fauna of Conservation Significance .......................................... 5 3.1.5 Likelihood of Occurrence – Fauna of Conservation Significance .................. 5 3.1.6 Taxonomy and Nomenclature ........................................................................ 6 3.2 SITE SURVEYS ....................................................................................................... 7 3.2.1 Fauna Habitat Assessment ........................................................................... -

Snakes of the Perth Metropolitan Area by G

Snakes of the Perth Metropolitan Area by G. M. Storr and R. E. Johnstone, Western Australian Museum Snakes are much-maligned animals. Yet most of the world's 3 000-odd species are harmless; less than 2% are dangerous to man or to his livestock and pets. It is therefore a good idea to learn which snakes are dangerous and which should be spared. But first one must distinguish snakes from other elongate limbless creatures. The presence of a very long, night; hence their vertical cat-like Snake (Pseudechis australis) and the slender, forked tongue and of large pupils. Locally there are only two Southern Death-adder (Acanthophis scales extending the full width of the species: the Carpet Python (Python antarctjcus). abdomen indicate a snake rather than spilotus), which reaches a total length Dugites and Gwardars have a legless lizard. The latter have a of a little more than two metres, and benefited from the opening up of the broad, ·unforked tongue and at least Children's Python (Liasis childreni) country and the introduction of the two longitudinal rows of scales along which is only half as long. The first House Mouse, which is now their the abdomen. Most legless lizards is a dark snake with a complex colour favourite food. They are large, also have an ear aperture, a feature pattern, the other a pale snake with slender, small-headed snakes with no found in no snake. The possession of irregular dark-brown markings. Both narrowing at the neck. All scales a dry (not slimy) skin and of nostrils are becoming rare in the metropolitan under the tail are in two longitudinal (instead of gill-slits) separates sea area. -

Fauna Assessment

Fauna Assessment Medcalf Vanadium Mining Project Proposed Haul Road Audalia Resources Limited November 2017 Version 2 On behalf of: Audalia Resources Ltd c/- Botanica Consulting PO Box 2027 BOULDER WA 6432 T: 08 9093 0024 F: 08 9093 1381 Prepared by: Greg Harewood Zoologist PO Box 755 BUNBURY WA 6231 M: 0402 141 197 E: [email protected] MEDCALF VANADIUM MINING PROJECT - PROPOSED HAUL ROAD – AUDALIA RESOURCES LIMITED FAUNA ASSESSMENT – NOVEMBER 2017 – V2 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 1 2. SCOPE OF WORKS .................................................................................. 1 3. METHODS ................................................................................................. 1 3.1 SITE SURVEYS ......................................................................................... 1 3.1.1 General Fauna Habitat Assessment ................................................ 1 3.1.2 Fauna Observations......................................................................... 2 3.2 POTENTIAL VERTEBRATE FAUNA INVENTORY ................................... 2 3.2.1 Database Searches ......................................................................... 2 3.2.2 Previous Fauna Surveys in the Area ............................................... 3 3.2.3 Existing Publications ........................................................................ 4 3.2.4 Fauna of Conservation Significance ............................................... -

A Biological Survey of the Eyre Peninsula South Australia

A BIOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE EYRE PENINSULA SOUTH AUSTRALIA R Brandle Science Resource Centre Information, Science and Technology Directorate Department for Environment and Heritage South Australia 2010 Eyre Peninsula Biological Survey The Biological Survey of the Eyre Peninsula was an initiative of the Biological Survey and Monitoring Section for the South Australian Department for Environment and Heritage The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the State Government of South Australia. The report may be cited as: Brandle, R. (2010). A Biological Survey of the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. (Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia). Limited hard copies of the report were prepared, but it can also be accessed from the Internet on: http://www.environment.sa.gov.au/biodiversity/biosurveys EDITOR R. Brandle – Science Resource Centre, Information Science & Technology, Department for Environment and Heritage. PO Box 1047 Adelaide 5001 AUTHORS R. Brandle, P. Lang, P. Canty, D. Armstrong – Science Resource Centre, Information Science & Technology, Department for Environment and Heritage. PO Box 1047 Adelaide 5001 G. Carpenter – Native Vegetation & Biodiversity Management Unit, Department of Water, Land & Biodiversity, GPO Box 2834. J. Cooper - PO Box 128, Port Lincoln SA. © Department for Environment and Heritage 2010 ISBN: 978-1-921466-42-7 Cover Photograph: A southern Eyre Peninsula view north from the Marble Range to South Block range. Photo: R Brandle ii Eyre Peninsula Biological Survey Abstract Specific objectives of the Biological Survey of the Eyre Peninsula Biogeographic Region were to collate the existing flora and fauna information and systematically sample the diversity of habitats present in the region for vertebrates.