Cross-Cultural Validation of the Positivity-Scale in Five European

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Micro-Reserves As a Tool for Conservation of Threatened Plants in Europe

The micro-reserves as a tool for conservation of threatened plants in Europe by Emilio Laguna Lumbreras Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Bern Convention) Nature and environment, No. 121 © Council of Europe Publishing, April 2001 The effort to make this work is dedicated in memoriam to ‘Capi’ Trillo, keeper of the botanical and zoological treasures of the Columbretes Islands Nature Reserve (Castellon, Valencian Community) who died in 1998, and to Jean Paul Galland, main French officer on plant conservation, who died in 1996. A c k n o w l e d g e m e n t s The author of this report would Aulikki ALANEN (Finnish Environment Institute, Helsinki, like to express his gratitude to Finland), the important effort made by Tatiana L. ANDRIENKO (Laboratory for Scientifical several collaborators. Many Fundamentals of Conservation, Kiev, Ukraine), thanks especially to Andrew BYFIELD (Fauna & Flora International / Dogal Ms Vicky Freeman and the Hayatu Koruma Dergeni, Istanbul, Turkey), World Conservation Monitoring Jan CEROVSKY, Maria MARSAKOVA and Podhajsza ZDENKA Centre (WCMC), for allowing (Czech Agence for Nature and Landscape Protection, Praha, access to providing global data Czech Republic), on protected areas of less than Natalia DANILINA (Zapovedniks Environmental Information 100 hectares for all European Centre, Moscow, Russian Federation), countries. The following people Viera FERÁKOVÁ and Ladislav JEDLICKA (Comenius – usually botanists Doctors or University, Bratislava, Slovakia), Professors at research -

IAEA Nuclear Energy Series Managing Counterfeit and Fraudulent Items in the Nuclear Industry No

IAEA Nuclear Energy Series IAEA Nuclear No. NP-T-3.26 No. IAEA Nuclear Energy Series Managing Counterfeit and Fraudulent Items in the Nuclear Industry Managing Counterfeit and Fraudulent Items in the Nuclear No. NP-T-3.26 Basic Managing Counterfeit Principles and Fraudulent Items in the Nuclear Industry Objectives Guides Technical Reports @ IAEA NUCLEAR ENERGY SERIES PUBLICATIONS STRUCTURE OF THE IAEA NUCLEAR ENERGY SERIES Under the terms of Articles III.A and VIII.C of its Statute, the IAEA is authorized to foster the exchange of scientific and technical information on the peaceful uses of atomic energy. The publications in the IAEA Nuclear Energy Series provide information in the areas of nuclear power, nuclear fuel cycle, radioactive waste management and decommissioning, and on general issues that are relevant to all of the above mentioned areas. The structure of the IAEA Nuclear Energy Series comprises three levels: 1 — Basic Principles and Objectives; 2 — Guides; and 3 — Technical Reports. The Nuclear Energy Basic Principles publication describes the rationale and vision for the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. Nuclear Energy Series Objectives publications explain the expectations to be met in various areas at different stages of implementation. Nuclear Energy Series Guides provide high level guidance on how to achieve the objectives related to the various topics and areas involving the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. Nuclear Energy Series Technical Reports provide additional, more detailed information on activities related to the various areas dealt with in the IAEA Nuclear Energy Series. The IAEA Nuclear Energy Series publications are coded as follows: NG — general; NP — nuclear power; NF — nuclear fuel; NW — radioactive waste management and decommissioning. -

Dušan Pajin FILOZOFIJA ŽIVOTA IVE ANDRIĆA APSTRAKT

THEORIA 4 https://doi.org/10.2298/THEO1904163P (2019) : 62 : str. 163-175 Originalni naučni rad Original Scientific Paper Dušan Pajin FILOZOFIJA ŽIVOTA IVE ANDRIĆA apstrakt: Moglo bi se reći da je Andrićeva knjiga Znakovi pored puta (prvi put objavljena 1976., tj. posle njegove smrti) na sažet, aforističan način izlaže njegovu filozofiju života, a pisana je u duhu sažetih zapažanja o čoveku i životu, donekle sličnim mudrostima Marka Aurelija (Aurelije, 1961). Ali, njegova filozofija života se ne nalazi samo u Znakovima (pisanim u prvom licu), nego u mnogim njegovim delima, posredno ili neposredno izražena kroz različite likove, njihove životne situacije, ili zaplete u koje zapadaju, kao i kroz stavove tih likova, prema životu i okruženju. ključne reči: filozofija života, intuicija, smisao umetnosti, mostovi Najpre je Andrić svoju filozofiju života uobličavao u deluEx Ponto (objavljeno u Zagrebu 1918. i Beogradu 1920), u kome je izrazio svoja iskustva i razmišljanja tokom vremena provedenog u zatvoru, tokom I. sv. rata. Naime, sredinom jula 1914. austrijska policija ga hapsi u Splitu i odvodi prvo u šibensku, a potom u mariborsku tamnicu u kojoj će, kao politički zatvorenik, ostati do marta 1915. g., a potom biva konfiniran (u kućnom zatvoru), u Ovčarevu i Zenici, gde ostaje sve do leta 1917. godine. Andrić je ovoj lirsko-meditativnoj prozi dao naslov koji ga na neki način povezuje sa zapisima Epistolae ex Ponto (Pisma sa Crnog mora) rimskog pesnika Ovidija (živeo od 43. g. st. – 17 g. n. ere), koji su nastali u poslednjem periodu Ovidijevog života (8-17. g.), kad je on živeo u progonstvu, na obali Crnog mora. -

BENEFIT-GUIDE.Pdf

This Document / Email is for internal usage. This Document / Email is for internal usage. SERBIA DISCOUNT WITH TRIZMA BENEFIT CARD: Publishing house Laguna was founded in 1998. From the • Laguna`s editions - 25% modest beginnings with several • Other publishers - 10% published titles in a year, they • Gift program - 10% have come to the production of • Birthday discount (that over 300 published titles annually and thus are one of the largest day at max 3 Laguna publishing houses in the country, books) - 40% and in the region. Laguna has been successfully A discount can be obtained operating for more than 15 years by using the Trizma benefit and builds its reputation as a card and Laguna Readers publishing leader with proven club card in each Laguna values. During the many years of bookshop in all the cities in doing business, Laguna's interests are inextricably intertwined with Serbia. the interests of the people and the community in which it operates. To take over part of its own responsibility, Laguna has taken a strategic focus on continuous www.laguna.rs investment in the local community and local projects. This Document / Email is for internal usage. STARI GRAD DISCOUNT WITH TRIZMA NOVI BEOGRAD BENEFIT CARD: NOVI SAD 20% discount on medical Founded in 1994, after 12 years services: of successful work, VIZIM General medicine / Family polyclinic was re-registered as doctor Internal Medicine / the First Private Health Center Cardiology US Diagnosis Physical "VIZIM". VIZIM consists of more medicine and rehabilitation than 40 permanent medical Dentistry Gynecology Pediatric doctors and other medical Ophthalmology ORL technicians. -

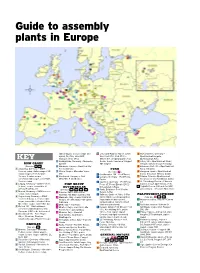

Guide to Assembly Plants in Europe

Guide to assembly plants in Europe station wagon, S-class sedan and B Lieu Saint-Amand, France (Sevel 3 Ruesselsheim, Germany – hybrid, CL, CLS, SLS AMG; Nord: Fiat 50%, PSA 50%) – Opel/Vauxhall Insignia, KEY Maybach (ends 2013) Citroen C8, Jumpy/Dispatch; Fiat Opel/Vauxhall Astra 5 Ludwigsfelde, Germany – Mercedes Scudo, Scudo Panorama; Peugeot 4 Luton, UK – Opel/Vauxhall Vivaro; BMW GROUP Sprinter 807, Expert Renault Trafic II; Nissan Primastar (See also 2 , 20 ) 6 Hambach, France – Smart ForTwo; 5 Ellesmere Port, UK – Opel/Vauxhall 1 Dingolfing, Germany – BMW ForTwo Electric FORD Astra, AstraVan 5-series sedan, station wagon, M5 7 Vitoria, Spain – Mercedes Viano, (See also 7 ) 6 Zaragoza, Spain – Opel/Vauxhall station wagon, 5-series Gran Vito 1 Southampton, UK – Ford Transit Corsa, CorsaVan, Meriva, Combo Turismo, 6-series coupe, 8 Kecskemet, Hungary – Next 2 Cologne, Germany – Ford Fiesta, 7 Gliwice, Poland – Opel/Vauxhall convertible, M6 coupe, convertible, Mercedes A and B class Fusion Astra Classic and Notchback, Zafira 7-series sedan 3 Saarlouis, Germany – Ford Focus, 8 St. Petersburg, Russia – Chevrolet 2 Leipzig, Germany – BMW 1-series FIAT GROUP Focus ST, Focus Electric (2012) Captiva, Cruze; Opel Antara, Astra (3 door), coupe, convertible, i3 AUTOMOBILES first-generation Kuga A Togliatti, Russia (GM and AvtoVAZ (2013), i8 (2014), X1 (See also 33 , 34 , 35 , 45 ) 4 Genk, Belgium – Ford Mondeo, joint venture) – Chevrolet Niva, Viva 3 Munich, Germany – BMW 3-series 1 Cassino, Italy – Alfa Romeo Galaxy, S-Max sedan, station wagon -

Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart Üniversitesi Uluslararasi Balkan Tarihi Ve Kültürü Sempozyumu 6-8 Ekim 2016, Çanakkale Bild

ÇANAKKALE ONSEKİZ MART ÜNİVERSİTESİ BALKAN VE EGE UYGULAMA VE ARAŞTIRMA MERKEZİ ULUSLARARASI BALKAN TARİHİ VE KÜLTÜRÜ SEMPOZYUMU 6-8 EKİM 2016, ÇANAKKALE BİLDİRİLER CİLT II EDİTÖR AŞKIN KOYUNCU Çanakkale, 2017 WHO ARE BOSNIAN MUSLIMS – LITERARY NARRATIVES ABOUT BOSNIA AND BOSNIAN MUSLIMS IN THE PERIOD OF SOCIALIST YUGOSLAVIA SABINA VELADŽIĆ* INTRODUCTION - THEORETICAL APPROACH In my article, I treat the phenomenon of the nation - the community of the modern era - as a construction fabricated by the cultural *intelligentsia through firmly structured ideological narrative which is mainly being disseminated towards the members of the imagined community by the institutions which were created and maintained by the state.1 What connects the modern community and creates a historical and social entity out of it is a culture, as a complex of symbolically mediated unity within which all can become a symbol that encodes this fellowship.2Production and reproduction, i.e., maintenance of the modern community is enabled by the educational infrastructure that systematically raise members of the national community through ideological-cultural concept embedded in the historical, literary, linguistic narrations which are being presented to the subjects during and primarily through the educational process. In fact, as the cultural theorist and one of the founders of the theory of cultural remembrance, Ian Assman, correctly observes, referring to the French social psychologist Maurice Halbwasch, all the mentioned narratives emerge as cultural achievements, -

![Arxiv:1912.08886V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 18 Dec 2019 Sumed to Have a Central Supermassive Black Hole, Surrounded by Crolensing, See, E.G., Popovic´ & Chartas 2005)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4107/arxiv-1912-08886v1-astro-ph-ga-18-dec-2019-sumed-to-have-a-central-supermassive-black-hole-surrounded-by-crolensing-see-e-g-popovic%C2%B4-chartas-2005-4344107.webp)

Arxiv:1912.08886V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 18 Dec 2019 Sumed to Have a Central Supermassive Black Hole, Surrounded by Crolensing, See, E.G., Popovic´ & Chartas 2005)

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. msLPopovic-3rd-rev c ESO 2021 September 1, 2021 Spectroscopy and polarimetry of the gravitationally lensed quasar SDSS J1004+4112 with the 6m SAO RAS telescope L. C.ˇ Popovic´1, V. L. Afanasiev2, A. Moiseev2; 3, A. Smirnova2, S. Simic´4, Dj. Savic´1; 5, E. G. Mediavilla6; 7, and C. Fian6 1 Astronomical Observatory, Volgina 7, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia e-mail: [email protected] 2 Special Astrophysical Observatory of the Russian AS, Nizhnij Arkhyz, Karachaevo-Cherkesia 369167, Russia 3 Space Research Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Profsoyuznaya ul. 84/32, Moscow 117997, Russia 4 Faculty of Sciences, University of Kragujevac, Radoja Domanovica 12, 34000 Kragujevac, Serbia 5 Université de Strasbourg, CNRS, Observatoire Astronomique de Strasbourg, UMR 7550, 11 rue de lUniversit, F-67000 Strasbourg, France 6 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, Vá Láctea S/N, La Laguna 38200, Tenerife, Spain 7 Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de la Laguna, La Laguna 38200, Tenerife, Spain Received September 15, 1996; accepted March 16, 1997 ABSTRACT Context. We present new spectroscopic and polarimetric observations of the gravitational lens SDSS J1004+4112 taken with the 6m telescope of the Special Astrophysical Observatory (SAO, Russia). Aims. In order to explain the variability that is observed only in the blue wing of the C IV emission line, corresponding to image A, we analyze the spectroscopy and polarimetry of the four images of the lensed system. Methods. Spectra of the four images were taken in 2007, 2008, and 2018, and polarization was measured in the period 2014-2017. Additionally, we modeled the microlensing effect in the polarized light, assuming that the source of polarization is the equatorial scattering in the inner part of the torus. -

Structural Characterization, Antimicrobial Activity and BSA/DNA Binding Affinity of New Silver(I) Complexes with Thianthrene and 1,8-Naphthyridine

molecules Article Structural Characterization, Antimicrobial Activity and BSA/DNA Binding Affinity of New Silver(I) Complexes with Thianthrene and 1,8-Naphthyridine Darko P. Ašanin 1 , Sanja Skaro Bogojevic 2 , Franc Perdih 3 , Tina P. Andrejevi´c 4, Dusan Milivojevic 2, Ivana Aleksic 2, Jasmina Nikodinovic-Runic 2,* , Biljana Ð. Gliši´c 4,* , Iztok Turel 3,* and Miloš I. Djuran 5,* 1 Department of Science, Institute for Information Technologies Kragujevac, University of Kragujevac, Jovana Cviji´cabb, 34000 Kragujevac, Serbia; [email protected] 2 Institute of Molecular Genetics and Genetic Engineering, University of Belgrade, Vojvode Stepe 444a, 11042 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] (S.S.B.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (I.A.) 3 Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Faculty of Chemistry and Chemical Technology, University of Ljubljana, Veˇcnapot 113, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] 4 Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Kragujevac, R. Domanovi´ca12, 34000 Kragujevac, Serbia; [email protected] 5 Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Knez Mihailova 35, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.N.-R.); [email protected] (B.Ð.G.); Citation: Ašanin, D.P.; Skaro [email protected] (I.T.); [email protected] (M.I.D.); Tel.: +381-11-397-6034 (J.N.-R.); +381-34-336-223 (B.Ð.G.); +386-14-798-525 (I.T.); +381-34-300-251 (M.I.D.) Bogojevic, S.; Perdih, F.; Andrejevi´c, T.P.; Milivojevic, D.; Aleksic, I.; Nikodinovic-Runic, J.; Gliši´c,B.Ð.; Abstract: Three new silver(I) complexes [Ag(NO3)(tia)(H2O)]n (Ag1), [Ag(CF3SO3)(1,8-naph)]n (Ag2) Turel, I.; Djuran, M.I. -

Lagunine Knjige, Vreme 1246, 19. Novembar 2014

knjigeLagunine i Laguna Književnost, istorija, politika preporučuju Ruske teme i motivi Knjige o Rusiji, od istoriografskih i beletrističkih dela do špijunskih trilera izdavačkoj industriji postoji pravilo da kako Vodeći savremeni britanski pisac politič- Uneka zemlja iz (geo)političkih razloga uđe u kih trilera Robert Heris radnju romana Ar- žižu globalne javnosti, počnu da se množe knji- hangelsk smestio je u Jeljcinovu Rusiju. „Kao ge koje se iz različitih uglova njome bave. Danas da je ukrstio Momke iz Brazila s poznim Le je to Rusija. I u izdavačkoj ponudi „Lagune“ nala- Kareom, Heris vas tera da prevrćete strani- zi se znatan broj knjiga napisanih na ruske teme, ce, na kojima zapanjujuće vešto bilo da je reč o istoriografskim, beletrističkim ili slika stvarnost postkomunistič- žanrovskim ostvarenjima. Evo nekih od njih. ke Rusije“, rečeno je o Arhangel- Engleski pisac Edvard Raderfurd specijalizo- sku. Drugi britanski autor, Tom vao se za pisanje monumentalnih istorijskih saga Rob Smit, svoje trilere je sme- koje se opisuju kao „biografi je gradova i zema- stio u kontekst Hladnog rata. Ju- lja“. Nakon Njujorka i Londona, „Laguna“ je upravo nak romana Dete 44, Tajni govor i objavila i njegovu dvotomnu sagu o ruskoj istoriji Agent 6 jeste ofi cir Državne bez- i civilizaciji pod nazivom Ruska. Junaci ovog romana su članovi bednosti SSSR-a i ratni heroj Lav nekoliko ruskih porodica različitog porekla i socijalnog položa- Demidov. Kada dobije naređe- ja, čije međusobno povezane i isprepletene hronike Raderfurd nje da sprovede istragu o svojoj prati iz generacije u generaciju tokom hiljadu i osamsto godina ženi, on dovodi u pitanje svoje ruske istorije, pripovedajući paralelno i o istorijskim događaji- komunističke ideale i posledič- ma i okolnostima koje su njihove sudbine usmeravale. -

TGC London Book Fair 2018 Guide

foreign rights London Book Fair 2018 www.thegernertco.com fiction Bryan Camp, THE CITY OF LOST FORTUNES The fate of New Orleans rests in the hands of a wayward grifter in this story of loss and re-birth after Hurricane Katrina. Urban fantasy Publisher: John Joseph Adams/HMH – April 17, 2018 Editor: John Joseph Adams Agent: Seth Fishman Material: Advanced Reader’s Copies Pre-empted by John Joseph Adams for his eponymous imprint • UK rights snapped up by Titan Books • Camp fashions a supernatural word barely hidden on the frinGe of society in his debut novel. There isn’t a dull paGe… Anne Rice fans will enjoy this fresh view of supernatural life in New Orleans, while fans of Kim Harrison’s urban fantasy will have a new author to watch.” —Booklist ( Starred review) • "Camp’s fantasy reads like jazz, with multiple chaotic-seeminG threads of deities, mortals, and destiny playinG in harmony. This Game of souls and fate is full of snarky dialoGue, taut suspense, and characters whose Glitter hides sharp fanGs. […] Any reader who likes fantasy with a dash of the bizarre will enjoy this trip to the Crescent City."—Publishers Weekly • "Take a walk down wild card shark streets into a world of Gods, lost souls, murder, and deep, dark maGic. You miGht not come back from The City of Lost Fortunes, but you’ll enjoy the trip."—Richard Kadrey, bestselling author of the Sandman Slim series • “A deft and expansive fantasy imbued with real maGic and wild plot turns.” —Kelly Link, the Hugo, Nebula, World Fantasy Award-winning author of the Pulitzer Prize-nominated Get In Trouble The post–Katrina New Orleans of The City of Lost Fortunes is a place haunted by its history and by the hurricane’s destruction, a place that is hopinG to survive the rebuildinG of its present lonG enouGh to ensure that it has a future. -

Greco (2005) 9E

DIRECTORATE GENERAL I œ LEGAL AFFAIRS DEPARTMENT OF CRIME PROBLEMS Strasbourg, 2 June 2005 Greco (2005) 9E 23rd Plenary Meeting of GRECO (Strasbourg, 17-20 May 2005) SUMMARY MEETING REPORT Secretariat du GRECO GRECO Secretariat www.greco.coe.int Conseil of l‘Europe Council of Europe F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex +33 3 88 41 20 00 Fax +33 3 88 41 39 55 I. Opening of the meeting 1. The 23rd Plenary Meeting of GRECO was chaired by the President, Mr Drago KOS (Slovenia) and by the Vice-President, Ms Isabelle VAN HEERS (Belgium) - for several items of the Agenda. The list of participants appears in Appendix I to this report. 2. The Vice-President opened the meeting and welcomed all representatives, referring in particular to those who had been newly nominated. II. Adoption of the agenda 3. The draft agenda was adopted as it appears in Appendix II to this report. III. Information provided by the President 4. The President reported on his participation in a ministerial conference of the Stability Pact for South Eastern Europe œ Anti-Corruption Initiative (SPAI) on —Joint Measures to Curb Corruption in South East Europe“ (Brussels, 11 May 2005). IV. Information provided by the Executive Secretary 5. The Executive Secretary reported on the following developments since GRECO‘s 22nd Plenary Meeting (March 2005), referring in particular to information provided in the Summary Report of Bureau 29 (Greco (2005) 7E): - the Ukrainian Law ratifying the Civil Law Convention on Corruption (ETS No. 174) was awaiting signature by the President of Ukraine. Once the instrument of ratification had been deposited with the Council of Europe, Ukraine would become the 40 th member of GRECO; - indications had been received from Austria that ratification of the Civil Law Convention on Corruption (ETS No. -

Lagunine Knjige, Vreme 1332, 14. Jul 2016

knjigeLagunine i Laguna Esejistika preporučuju Nove knjige o terorizmu, korporativnom kapitalizmu, ratovima na Bliskom istoku i uzrocima aktuelne globalne političke i ekonomske krize konomska kriza, terorizam, ratovi na Bliskom sa Iranom ili rat u Siriji, mmora da se pozabavi politi- istoku i u Ukrajini, migranttsko pitanje, nova kom Zapada i njenim utticajem na taj region posle hladnoratovska napetost, poliitička previranja u Drugog svetskog rata.”Dubinski upućen u temu o Evropi, opšta nestabilnost i neizzvesnost, sve su to kojoj piše, obavešten i oobrazovan, Liders je pouz- pitanja koja s pravom uznemirruju javnost. U po- dan vodič i kredibilan svvedok za ovaj deo sveta. kušaju da se aktuelni procesi raazumeju i da se na Knjiga austrijskih istraživača Hansa Vajsa i Kla- goruća pitanja ponude neki odgovori, nastaju usa Verner-Loboa Crnaa knjiga korporacija, čije kritičke knjige posvećene različitim segmentima prvo izdanje je objavljeeno 2001, danas se, uz No globalne krize. Evo najnovijih. logo! Naomi Klajn, smatrra jednom od najsnažnijih Migrantska kriza, kao ni opasnost od tero- kritika korporativne globalizacije sveta i „biblijom rizma, ne jenjavaju, a jedan od najvažnijih nji- antiglobalizma“. Ona se bavi analizom delovanja hovih generatora jeste uspon ISIS-a i nastanak „Islamske dr- pedesetak najvećih multinacionalnnih kompanija farmaceut- žave”. D v a nova „Lagunina” izdanja bave se upravo ovim pro- ske, naftne, tekstilne, prehrambenee, medijske, IT i drugih in- blemom. Knjigu Deset dana u „Islamskoj državi”” napisao je Ji- dustrija, kao i vezama politike, korrporacija i međunarodnih rgen Todenhefer, doktor pravnnih nauka, dugodišnji poslanik institucija. Autori objašnjavaju čimme se sve služe korporacije CDU u nemačkom Bundestaguu, nekadašnji direktor jedne ve- u cilju uspostavljanja monopola naa tržištu i zgrtanja profita, like nemačke medijske kuće, publicista i oštar kritičar rata i in- kako se kreiraju i održavaju koruptivni sistemi i kakve to po- tervencionističke politike.