The Ptolemaic Sea Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Monopteros in the Athenian Agora

THE MONOPTEROS IN THE ATHENIAN AGORA (PLATE 88) O SCAR Broneerhas a monopterosat Ancient Isthmia. So do we at the Athenian Agora.' His is middle Roman in date with few architectural remains. So is ours. He, however, has coins which depict his building and he knows, from Pau- sanias, that it was built for the hero Palaimon.2 We, unfortunately, have no such coins and are not even certain of the function of our building. We must be content merely to label it a monopteros, a term defined by Vitruvius in The Ten Books on Architecture, IV, 8, 1: Fiunt autem aedes rotundae, e quibus caliaemonopteroe sine cella columnatae constituuntur.,aliae peripteroe dicuntur. The round building at the Athenian Agora was unearthed during excavations in 1936 to the west of the northern end of the Stoa of Attalos (Fig. 1). Further excavations were carried on in the campaigns of 1951-1954. The structure has been dated to the Antonine period, mid-second century after Christ,' and was apparently built some twenty years later than the large Hadrianic Basilica which was recently found to its north.4 The lifespan of the building was comparatively short in that it was demolished either during or soon after the Herulian invasion of A.D. 267.5 1 I want to thank Professor Homer A. Thompson for his interest, suggestions and generous help in doing this study and for his permission to publish the material from the Athenian Agora which is used in this article. Anastasia N. Dinsmoor helped greatly in correcting the manuscript and in the library work. -

A Comparative Study of Ancient Greek City Walls in North-Western Black Sea During the Classical and Hellenistic Times

INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES MA IN BLACK SEA CULTURAL STUDIES A comparative study of ancient Greek city walls in North-Western Black Sea during the Classical and Hellenistic times Thessaloniki, 2011 Supervisor’s name: Professor Akamatis Ioannis Student’s name: Fantsoudi Fotini Id number:2201100018 Abstract Greek presence in the North Western Black Sea Coast is a fact proven by literary texts, epigraphical data and extensive archaeological remains. The latter in particular are the most indicative for the presence of walls in the area and through their craftsmanship and techniques being used one can closely relate these defensive structures to the walls in Asia Minor and the Greek mainland. The area examined in this paper, lies from ancient Apollonia Pontica on the Bulgarian coast and clockwise to Kerch Peninsula.When establishing in these places, Greeks created emporeia which later on turned into powerful city states. However, in the early years of colonization no walls existed as Greeks were starting from zero and the construction of walls needed large funds. This seems to be one of the reasons for the absence of walls of the Archaic period to which lack comprehensive fieldwork must be added. This is also the reason why the Archaic period is not examined, but rather the Classical and Hellenistic until the Roman conquest. The aim of Greeks when situating the Black Sea was to permanently relocate and to become autonomous from their mother cities. In order to be so, colonizers had to create cities similar to their motherlands. More specifically, they had to build public buildings, among which walls in order to prevent themselves from the indigenous tribes lurking to chase away the strangers from their land. -

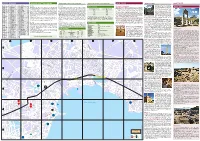

1 2 3 4 5 a B C D E

STREET REGISTER ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE Amurskaya E/F-2 Krasniy Spusk G-3 Radishcheva E-5 By Bus By Plane Great Mitridat Stairs C-4, near the Lenina Admirala Vladimirskogo E/F-3 Khersonskaya E/F-3 Rybatskiy prichal D/C-4-B-5 Churches & Cathedrals pl. The stairs were built in the 1930’s with plans Ancient Cities Admirala Azarova E-4/5 Katernaya E-3 Ryabova F-4 Arriving by bus is the only way to get to Kerch all year round. The bus station There is a local airport in Kerch, which caters to some local Crimean flights Ferry schedule Avdeyeva E-5 Korsunskaya E-3 Repina D-4/5 Church of St. John the Baptist C-4, Dimitrova per. 2, tel. (+380) 6561 from the Italian architect Alexander Digby. To save Karantinnaya E-3 Samoylenko B-3/4 itself is a buzzing place thanks to the incredible number of mini-buses arriving during the summer season, but the only regular flight connection to Kerch is you the bother we have already counted them; Antonenko E-5 From Kerch (from Port Krym) To Kerch (from Port Kavkaz) 222 93. This church is a unique example of Byzantine architecture. It was built in Admirala Fadeyeva A/B-4 Kommunisticheskaya E-3-F-5 Sladkova C-5 and departing. Marshrutkas run from here to all of the popular destinations in through Simferopol State International, which has regular flights to and from Kyiv, there are 432 steps in all meandering from the Dep. -

Great Waterworks in Roman Greece Aqueducts and Monumental Fountain Structures Function in Context

Great Waterworks in Roman Greece Aqueducts and Monumental Fountain Structures Function in Context Access edited by Open Georgia A. Aristodemou and Theodosios P. Tassios Archaeopress Archaeopress Roman Archaeology 35 © Archaeopress and the authors, 2017. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 764 7 ISBN 978 1 78491 765 4 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the authors 2018 Cover: The monumental arcade bridge of Moria,Access Lesvos, courtesy of Dr Yannis Kourtzellis Creative idea of Tasos Lekkas (Graphics and Web Designer, International Hellenic University) Open All rights Archaeopressreserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Oxuniprint, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com © Archaeopress and the authors, 2017. Contents Preface ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� iii Georgia A. Aristodemou and Theodosios P. Tassios Introduction I� Roman Aqueducts in Greece �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������1 Theodosios P. Tassios Introduction II� Roman Monumental Fountains (Nymphaea) in Greece �����������������������������������������10 Georgia A. Aristodemou PART I: AQUEDUCTS Vaulted-roof aqueduct channels in Roman -

Andrea F. Gatzke, Mithridates VI Eupator and Persian Kingship

The Ancient History Bulletin VOLUME THIRTY-THREE: 2019 NUMBERS 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson ò Michael Fronda òDavid Hollander Timothy Howe ò John Vanderspoel Pat Wheatley ò Sabine Müller òAlex McAuley Catalina Balmacedaò Charlotte Dunn ISSN 0835-3638 ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Volume 33 (2019) Numbers 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson, Catalina Balmaceda, Michael Fronda, David Hollander, Alex McAuley, Sabine Müller, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Assistant Editor: Charlotte Dunn Editorial correspondents Elizabeth Baynham, Hugh Bowden, Franca Landucci Gattinoni, Alexander Meeus, Kurt Raaflaub, P.J. Rhodes, Robert Rollinger, Victor Alonso Troncoso Contents of volume thirty-three Numbers 1-2 1 Kathryn Waterfield, Penteconters and the Fleet of Polycrates 19 John Hyland, The Aftermath of Aigospotamoi and the Decline of Spartan Naval Power 42 W. P. Richardson, Dual Leadership in the League of Corinth and Antipater’s Phantom Hegemony 60 Andrea F. Gatzke, Mithridates VI Eupator and Persian Kingship NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS AND SUBSCRIBERS The Ancient History Bulletin was founded in 1987 by Waldemar Heckel, Brian Lavelle, and John Vanderspoel. The board of editorial correspondents consists of Elizabeth Baynham (University of Newcastle), Hugh Bowden (Kings College, London), Franca Landucci Gattinoni (Università Cattolica, Milan), Alexander Meeus (University of Mannhiem), Kurt Raaflaub (Brown University), P.J. Rhodes (Durham University), Robert Rollinger (Universität Innsbruck), Victor Alonso Troncoso (Universidade da Coruña) AHB is currently edited by: Timothy Howe (Senior Editor: [email protected]), Edward Anson, Catalina Balmaceda, Michael Fronda, David Hollander, Alex McAuley, Sabine Müller, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley and Charlotte Dunn. AHB promotes scholarly discussion in Ancient History and ancillary fields (such as epigraphy, papyrology, and numismatics) by publishing articles and notes on any aspect of the ancient world from the Near East to Late Antiquity. -

Crimea______9 3.1

CONTENTS Page Page 1. Introduction _____________________________________ 4 6. Transport complex ______________________________ 35 1.1. Brief description of the region ______________________ 4 1.2. Geographical location ____________________________ 5 7. Communications ________________________________ 38 1.3. Historical background ____________________________ 6 1.4. Natural resource potential _________________________ 7 8. Industry _______________________________________ 41 2. Strategic priorities of development __________________ 8 9. Energy sector ___________________________________ 44 3. Economic review 10. Construction sector _____________________________ 46 of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea ________________ 9 3.1. The main indicators of socio-economic development ____ 9 11. Education and science ___________________________ 48 3.2. Budget _______________________________________ 18 3.3. International cooperation _________________________ 20 12. Culture and cultural heritage protection ___________ 50 3.4. Investment activity _____________________________ 21 3.5. Monetary market _______________________________ 22 13. Public health care ______________________________ 52 3.6. Innovation development __________________________ 23 14. Regions of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea _____ 54 4. Health-resort and tourism complex_________________ 24 5. Agro-industrial complex __________________________ 29 5.1. Agriculture ____________________________________ 29 5.2. Food industry __________________________________ 31 5.3. Land resources _________________________________ -

History of Phanagoria

Ассоциация исследователей ИНСТИТУТ АРХЕОЛОГИИ РАН ФАНАГОРИЙСКАЯ ЭКСПЕДИЦИЯ ИА РАН PHANAGORIA EDITED BY V.D. KUZNETSOV Moscow 2016 904(470.62) 63.443.22(235.73) Утверждено к печати Ученым советом Института археологии РАН Edited by V.D. Kuznetsov Text: Abramzon M.G., PhD, Professor, Magnitogorsk State Technical University Voroshilov A.N., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Voroshilova O.N., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Garbuzov G.P., PhD, Southern Scientific Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Rostov-on-Don) Golofast L.A., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Gunchina O.L., conservator-restorer, Phanagoria Museum-Preserve Dobrovolskaya E.V., PhD, A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences Dobrovolskaya M.V., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Zhukovsky M.O., Deputy Director of the Phanagoria Museum-Preserve Zavoikin A.A., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Zavoikina N.V., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Kokunko G.V., Historical and Cultural Heritage of Kuban Program Coordinator Kuznetsov V.D., PhD, Director of the Phanagoria Museum-Preserve, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Kuzmina (Shorunova) Yu.N., PhD, Curator of the Phanagoria Museum-Preserve, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Olkhovsky S.V., Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Pavlichenko N.A., PhD, Institute of History, Russian Academy of Sciences Saprykina I.A., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Published with financial support from the Volnoe Delo Oleg Deripaska Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission of the copyright owners. -

The Shaping of the New Macedonia (1798-1870)

VIII. The shaping of the new Macedonia (1798-1870) by Ioannis Koliopoulos 1. Introduction Macedonia, both the ancient historical Greek land and the modern geographical region known by that name, has been perhaps one of the most heavily discussed countries in the world. In the more than two centuries since the representatives of revolutionary France introduced into western insular and continental Greece the ideas and slogans that fostered nationalism, the ancient Greek country has been the subject of inquiry, and the object of myth-making, on the part of archaeologists, historians, ethnologists, political scientists, social anthropologists, geographers and anthropogeographers, journalists and politicians. The changing face of the ancient country and its modern sequel, as recorded in the testimonies and studies of those who have applied themselves to the subject, is the focus of this present work. Since the time, two centuries ago, when the world’s attention was first directed to it, the issue of the future of this ancient Greek land – the “Macedonian Question” as it was called – stirred the interest or attracted the involvement of scientists, journalists, diplomats and politicians, who moulded and remoulded its features. The periodical cri- ses in the Macedonian Question brought to the fore important researchers and generated weighty studies, which, however, with few exceptions, put forward aspects and charac- teristics of Macedonia that did not always correspond to the reality and that served a variety of expediencies. This militancy on the part of many of those who concerned themselves with the ancient country and its modern sequel was, of course, inevitable, given that all or part of that land was claimed by other peoples of south-eastern Europe as well as the Greeks. -

Persian Imperial Policy Behind the Rise and Fall of the Cimmerian Bosporus in the Last Quarter of the Sixth to the Beginning of the Fifth Century BC

Persian Imperial Policy Behind the Rise and Fall of the Cimmerian Bosporus in the Last Quarter of the Sixth to the Beginning of the Fifth Century BC Jens Nieling The aim of the following paper is to recollect arguments for the hypotheses of a substantial Persian interference in the Greek colonies of the Cimmerian Bosporus and that they remained not untouched by Achaemenid policy in western Anatolia. The settlements ought to have been affected positively in their prime in the last quarter of the sixth century, but also harmed during their first major crisis at the beginning of the fifth century and afterwards. A serious break in the tight interrelationship between the Bosporan area and Achaemenid Anatolia occurred through the replacement of the Archaeanactid dynasty, ruling the Cimmerian Bosporus from 480 onwards, in favour of the succeeding Spartocids by an Athenian naval expedition under the command of Pericles in the year 438/437.1 The assumption of a predominant Persian influence to the north of the Caucasus mountains contradicts the still current theory of V. Tolstikov2 and the late Yu.G. Vinogradov,3 who favour instead a major Scythian or local impact as a decisive factor at the Bosporan sites.4 To challenge this traditional posi- tion, this paper will follow the successive stages of architectural development in the central settlement of Pantikapaion on its way to becoming the capital of the region. The argumentation is necessarily based on a parallelization of stratigraphical evidence with historical sources, since decisive archaeological data to support either the Persian or the Scythian hypothesis are few. -

Alexander the Great in His World

Alexander the Great in his World Carol G. Thomas Alexander the Great in his World Blackwell Ancient Lives At a time when much scholarly writing on the ancient world is abstract and analytical, this series presents engaging, accessible accounts of the most influential figures of antiquity. It re-peoples the ancient landscape; and while never losing sight of the vast gulf that separates antiquity from our own world, it seeks to communicate the delight of reading historical narratives to discover “what happened next.” Published Alexander the Great in his World Carol G. Thomas Nero Jürgen Malitz Tiberius Robin Seager King Hammurabi of Babylon Marc Van De Mieroop Pompey the Great Robin Seager Age of Augustus Werner Eck Hannibal Serge Lancel In Preparation Cleopatra Sally Ann-Ashton Constantine the Great Timothy Barnes Pericles Charles Hamilton Julius Caesar W. Jeffrey Tatum Alexander the Great in his World Carol G. Thomas © 2007 by Carol G. Thomas BLACKWELL PUBLISHING 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton,Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Carol G. Thomas to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2007 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1 2007 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Thomas, Carol G., 1938– Alexander the Great in his world / Carol G. -

The Chora of Nymphaion (6Th Century BC-6Th Century

The Chora of Nymphaion (6th century BC-6th century AD) Viktor N. Zin’ko The exploration of the rural areas of the European Bosporos has gained in scope over the last decades. Earlier scholars focused on studying particular archaeological sites and an overall reconstruction of the rural territories of the Bosporan poleis as well as on a general understanding of the polis-chora relationship.1 These works did not aim at an in-depth study of the chora of any one particular city-state limited as they were to small-scale excavations of individual settlements. In 1989, the author launched a comprehensive research project on the chora of Nymphaion. A careful examination of archive materials and the results of the surveys revealed an extensive number of previously unknown archaeological sites. The limits of Nymphaion’s rural territory corresponded to natural bor- der-lines (gullies, steep slopes of ridges etc.) impassable to the Barbarian cav- alry. The region has better soils than the rest of the peninsula, namely dark chestnut černozems,2 and the average level of precipitation is 100 mm higher than in other areas.3 The core of the territory was represented by fertile lands, Fig. 1. Map of the Kimmerian Bosporos (hatched – chora of Nymphaion in the 5th century BC; cross‑hatched – chora of Nymphaion in the 4th‑early 3rd centuries BC). 20 Viktor N. Zin’ko stretching from the littoral inland, and bounded to the north and south by two ravines situated 7 km apart. The two ravines originally began at the western extremities of the ancient estuaries (now the Tobečik and Čurubaš Lakes). -

About Thessaloniki

INFORMATION ON THESSALONIKI Thessaloniki is one of the oldest cities in Europe and the second largest city in Greece. It was founded in 315 B.C. by Cassander, King of Macedonia and was named after his wife Thessaloniki, sister of Alexander the Great. Today Thessaloniki is considered to be one of the most important trade and communication centers in the Mediterranean. This is evident from its financial and commercial activities as well as its geographical position and its infrastructure. As a historic city Thessaloniki is well – known from its White Tower dating from the middle of the 15th century in its present form. Thessaloniki presents a series of monuments from Roman and Byzantine times. It is known for its museums, Archaeological and Byzantine as well as for its Art, Historical and War museums and Galleries. Also, it is known for its Churches, particularly the church of Agia Sophia and the church of Aghios Dimitrios, the patron Saint of the city. Thessaloniki’s infrastructure, which includes the Universities campus, the International trade, its port and airport as well as its road rail network, increases the city’s reputation; it is also famous for its entertainment, attractions, gastronomy, shopping and even more. A place that becomes a vacation resort for many citizens of Thessaloniki especially in the summer and only 45 minutes away is Chalkidiki. Chalkidiki is a beautiful place, which combines the sea with the mountain. Today, Chalkidiki is a summer resort for the people of Thessaloniki. It is really a gifted place due to its natural resources, its crystal waters and also the graphical as well as traditional villages.