A Comparative Research Between the Macedonian Tombs and the Scythian Kurgans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Municipal Solid Waste Management in Greece

Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity Article Description and Economic Evaluation of a “Zero-Waste Mortar-Producing Process” for Municipal Solid Waste Management in Greece Alexandros Sikalidis 1,2 and Christina Emmanouil 3,* 1 Amsterdam Business School, Accounting Section, University of Amsterdam, 1012 WX Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2 Faculty of Economics, Business and Legal Studies, International Hellenic University, 57001 Thessaloniki, Greece 3 School of Spatial Planning and Development, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-2310-995638 Received: 2 July 2019; Accepted: 19 July 2019; Published: 23 July 2019 Abstract: The constant increase of municipal solid wastes (MSW) as well as their daily management pose a major challenge to European countries. A significant percentage of MSW originates from household activities. In this study we calculate the costs of setting up and running a zero-waste mortar-producing (ZWMP) process utilizing MSW in Northern Greece. The process is based on a thermal co-processing of properly dried and processed MSW with raw materials (limestone, clay materials, silicates and iron oxides) needed for the production of clinker and consequently of mortar in accordance with the Greek Patent 1003333, which has been proven to be an environmentally friendly process. According to our estimations, the amount of MSW generated in Central Macedonia, Western Macedonia and Eastern Macedonia and Thrace regions, which is conservatively estimated at 1,270,000 t/y for the year 2020 if recycling schemes in Greece are not greatly ameliorated, may sustain six ZWMP plants while offering considerable environmental benefits. This work can be applied to many cities and areas, especially when their population generates MSW at the level of 200,000 t/y, hence requiring one ZWMP plant for processing. -

The Monopteros in the Athenian Agora

THE MONOPTEROS IN THE ATHENIAN AGORA (PLATE 88) O SCAR Broneerhas a monopterosat Ancient Isthmia. So do we at the Athenian Agora.' His is middle Roman in date with few architectural remains. So is ours. He, however, has coins which depict his building and he knows, from Pau- sanias, that it was built for the hero Palaimon.2 We, unfortunately, have no such coins and are not even certain of the function of our building. We must be content merely to label it a monopteros, a term defined by Vitruvius in The Ten Books on Architecture, IV, 8, 1: Fiunt autem aedes rotundae, e quibus caliaemonopteroe sine cella columnatae constituuntur.,aliae peripteroe dicuntur. The round building at the Athenian Agora was unearthed during excavations in 1936 to the west of the northern end of the Stoa of Attalos (Fig. 1). Further excavations were carried on in the campaigns of 1951-1954. The structure has been dated to the Antonine period, mid-second century after Christ,' and was apparently built some twenty years later than the large Hadrianic Basilica which was recently found to its north.4 The lifespan of the building was comparatively short in that it was demolished either during or soon after the Herulian invasion of A.D. 267.5 1 I want to thank Professor Homer A. Thompson for his interest, suggestions and generous help in doing this study and for his permission to publish the material from the Athenian Agora which is used in this article. Anastasia N. Dinsmoor helped greatly in correcting the manuscript and in the library work. -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

Download Excerpt (Pdf-Format)

Towards Determining the Chief Function of the Settlement of Borysthenes Jaroslav V. Domanskij & Konstantin K. Marcenko The site of Borysthenes, the earliest Greek settlement in the northern Black Sea area, is located on the island of Berezan’ situated at the mouth of the estuaries of the Dnieper and Bug rivers. The large-scale historical and archaeological research currently being carried out there has already yield- ed a number of significant discoveries. Of particular importance is some additional evidence recently obtained on the date of the origin of this colony, its outward appearance, culture, and historical development, as well as its relations with the barbarians of the hinterland.1 Yet the most important result of the excavations of recent years is the discovery of the sacred precinct at the settlement – the temenos with the remains of the Temple of Aphrodite from the second half of the 6th and beginning of the 5th century BC.2 It is possible that this fact may tip the balance, at least for now, in favour of the hypothesis about the polis status of Borysthenes. Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that the very important question about the causes of and motivation behind the appearance of the first group of colonists in this remote region of the Greek oikoumene – i.e. the question about the basic function of early Borysthenes – has remained extremely con- troversial. In this respect, almost the entire conceivable spectrum of ideas and concepts co-exists comfortably in modern historiography. The question is, indeed, difficult to answer, not only with respect to Borysthenes itself but also to many other Greek settlements in the northern Black Sea area, and although there seem to be answers for the period of the mature and fully developed existence of the Greek cities, the problem becomes extremely complicated when focussing on the period of the formation and initial devel- opment of these cities. -

The Religious Tourism As a Competitive Advantage of the Prefecture of Pieria, Greece

Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, May-June 2021, Vol. 9, No. 3, 173-181 doi: 10.17265/2328-2169/2021.03.005 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Religious Tourism as a Competitive Advantage of the Prefecture of Pieria, Greece Christos Konstantinidis International Hellenic University, Serres, Greece Christos Mystridis International Hellenic University, Serres, Greece Eirini Tsagkalidou Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece Evanthia Rizopoulou International Hellenic University, Serres, Greece The scope of the present paper is the research of whether the prefecture of Pieria comprises an attractive destination for religious tourism and pilgrimage. For this reason, the use of questionnaires takes place which aims to realizing if and to what extend this form of tourism comprises a comparative and competitive advantage for the prefecture of Pieria. The research method of this paper is the qualitative research and more specifically the use of questionnaires with 13 questions in total. The scope was to research whether the prefecture of Pieria is a religious-pilgrimage destination. The sample is comprised of 102 participants, being Greek residents originating from other Greek counties, the European Union, and Third World Countries. The requirement was for the participant to have visited the prefecture of Pieria. The independency test (x2) was used for checking the interconnections between the different factors, while at the same time an allocation of frequencies was conducted based on the study and presentation of frequency as much as relevant frequency. Due to the fact that, no other similar former researches have been conducted regarding religious tourism in Pieria, this research will be able to give some useful conclusions. -

9 · the Growth of an Empirical Cartography in Hellenistic Greece

9 · The Growth of an Empirical Cartography in Hellenistic Greece PREPARED BY THE EDITORS FROM MATERIALS SUPPLIED BY GERMAINE AUJAe There is no complete break between the development of That such a change should occur is due both to po cartography in classical and in Hellenistic Greece. In litical and military factors and to cultural developments contrast to many periods in the ancient and medieval within Greek society as a whole. With respect to the world, we are able to reconstruct throughout the Greek latter, we can see how Greek cartography started to be period-and indeed into the Roman-a continuum in influenced by a new infrastructure for learning that had cartographic thought and practice. Certainly the a profound effect on the growth of formalized know achievements of the third century B.C. in Alexandria had ledge in general. Of particular importance for the history been prepared for and made possible by the scientific of the map was the growth of Alexandria as a major progress of the fourth century. Eudoxus, as we have seen, center of learning, far surpassing in this respect the had already formulated the geocentric hypothesis in Macedonian court at Pella. It was at Alexandria that mathematical models; and he had also translated his Euclid's famous school of geometry flourished in the concepts into celestial globes that may be regarded as reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-246 B.C.). And it anticipating the sphairopoiia. 1 By the beginning of the was at Alexandria that this Ptolemy, son of Ptolemy I Hellenistic period there had been developed not only the Soter, a companion of Alexander, had founded the li various celestial globes, but also systems of concentric brary, soon to become famous throughout the Mediter spheres, together with maps of the inhabited world that ranean world. -

Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

ANTONIJE SHKOKLJEV SLAVE NIKOLOVSKI - KATIN PREHISTORY CENTRAL BALKANS CRADLE OF AEGEAN CULTURE Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 -

A Comparative Study of Ancient Greek City Walls in North-Western Black Sea During the Classical and Hellenistic Times

INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES MA IN BLACK SEA CULTURAL STUDIES A comparative study of ancient Greek city walls in North-Western Black Sea during the Classical and Hellenistic times Thessaloniki, 2011 Supervisor’s name: Professor Akamatis Ioannis Student’s name: Fantsoudi Fotini Id number:2201100018 Abstract Greek presence in the North Western Black Sea Coast is a fact proven by literary texts, epigraphical data and extensive archaeological remains. The latter in particular are the most indicative for the presence of walls in the area and through their craftsmanship and techniques being used one can closely relate these defensive structures to the walls in Asia Minor and the Greek mainland. The area examined in this paper, lies from ancient Apollonia Pontica on the Bulgarian coast and clockwise to Kerch Peninsula.When establishing in these places, Greeks created emporeia which later on turned into powerful city states. However, in the early years of colonization no walls existed as Greeks were starting from zero and the construction of walls needed large funds. This seems to be one of the reasons for the absence of walls of the Archaic period to which lack comprehensive fieldwork must be added. This is also the reason why the Archaic period is not examined, but rather the Classical and Hellenistic until the Roman conquest. The aim of Greeks when situating the Black Sea was to permanently relocate and to become autonomous from their mother cities. In order to be so, colonizers had to create cities similar to their motherlands. More specifically, they had to build public buildings, among which walls in order to prevent themselves from the indigenous tribes lurking to chase away the strangers from their land. -

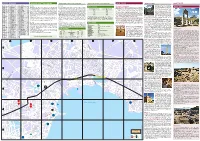

1 2 3 4 5 a B C D E

STREET REGISTER ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE Amurskaya E/F-2 Krasniy Spusk G-3 Radishcheva E-5 By Bus By Plane Great Mitridat Stairs C-4, near the Lenina Admirala Vladimirskogo E/F-3 Khersonskaya E/F-3 Rybatskiy prichal D/C-4-B-5 Churches & Cathedrals pl. The stairs were built in the 1930’s with plans Ancient Cities Admirala Azarova E-4/5 Katernaya E-3 Ryabova F-4 Arriving by bus is the only way to get to Kerch all year round. The bus station There is a local airport in Kerch, which caters to some local Crimean flights Ferry schedule Avdeyeva E-5 Korsunskaya E-3 Repina D-4/5 Church of St. John the Baptist C-4, Dimitrova per. 2, tel. (+380) 6561 from the Italian architect Alexander Digby. To save Karantinnaya E-3 Samoylenko B-3/4 itself is a buzzing place thanks to the incredible number of mini-buses arriving during the summer season, but the only regular flight connection to Kerch is you the bother we have already counted them; Antonenko E-5 From Kerch (from Port Krym) To Kerch (from Port Kavkaz) 222 93. This church is a unique example of Byzantine architecture. It was built in Admirala Fadeyeva A/B-4 Kommunisticheskaya E-3-F-5 Sladkova C-5 and departing. Marshrutkas run from here to all of the popular destinations in through Simferopol State International, which has regular flights to and from Kyiv, there are 432 steps in all meandering from the Dep. -

Archaeological Anastylosis of Two Macedonian Tombs In

Virtual Archaeology Review, 11(22): 26-40, 2020 https://doi.org/10.4995/var.2020.11877 © UPV, SEAV, 2015 Received: May 22, 2019 Accepted: July 25, 2019 ARCHAEOLOGICAL ANASTYLOSIS OF TWO MACEDONIAN TOMBS IN A 3D VIRTUAL ENVIRONMENT LA ANASTILOSIS ARQUEOLÓGICA DE DOS TUMBAS MACEDONIAS EN UN AMBIENTE VIRTUAL 3D Maria Stampoulogloua, Olympia Toskab, Sevi Tapinakic, Georgia Kontogiannic , Margarita Skamantzaric, Andreas Georgopoulosc,* aSerres Ephorate of Antiquities, Eth. Antistasis 36-48, Serres, 62122 Greece. [email protected] bDepartment of Mediterranean Studies, University of the Aegean, Dimokratias Ave. 1, Rhodes, 85132 Greece. [email protected] cLaboratory of Photogrammetry, National Technical University of Athens, Iroon Polytechniou 9, Zografos, Athens, 15780 Greece. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Highlights: Use of contemporary digital methods for the 3D geometric documentation of complex burial structures. Interdisciplinary approach to implement digital techniques for 3D modelling, including 3D terrestrial laser scanning and image-based modelling. Implementation of virtual anastylosis by archaeologists using the 3D models and suitable software. Abstract: Archaeological restoration of monuments is a practice requiring extreme caution and thorough study. Proceeding to restoration or to reconstruction actions without detailed consultation and thought is normally avoided by archaeologists and conservation experts. Nowadays, anastylosis executed on the real object is generally prohibited. Contemporary technologies have provided archaeologists and other conservation experts with the tools to embark on virtual restorations or anastyloses, thus testing various alternatives without physical intervention on the monument itself. In this way, the values of the monuments are respected according to international conventions. In this paper, two examples of virtual archaeological anastyloses of two important Macedonian tombs in northern Greece are presented. -

Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: a Socio-Cultural Perspective

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective Nicholas D. Cross The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1479 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INTERSTATE ALLIANCES IN THE FOURTH-CENTURY BCE GREEK WORLD: A SOCIO-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE by Nicholas D. Cross A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Nicholas D. Cross All Rights Reserved ii Interstate Alliances in the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________ __________________________________________ Date Jennifer Roberts Chair of Examining Committee ______________ __________________________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Joel Allen Liv Yarrow THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Interstate Alliances of the Fourth-Century BCE Greek World: A Socio-Cultural Perspective by Nicholas D. Cross Adviser: Professor Jennifer Roberts This dissertation offers a reassessment of interstate alliances (συµµαχία) in the fourth-century BCE Greek world from a socio-cultural perspective. -

Amphora Graffiti from the Byzantine Shipwreck at Novy Svet, Crimea

AMPHORA GRAFFITI FROM THE BYZANTINE SHIPWRECK AT NOVY SVET, CRIMEA A Thesis by CLAIRE ALIKI COLLINS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Deborah Carlson Committee Members, Filipe Vieira de Castro Nancy Klein Head of Department, Cynthia Werner December 2012 Major Subject: Anthropology Copyright 2012 Claire Aliki Collins ABSTRACT The thesis presents the results of a study of 1005 graffiti on 13th century Byzantine amphorae from a shipwreck in the Bay of Sudak near Novy Svet, Crimea, Ukraine. The primary goals of this thesis are 1) to provide an overview of the excavation and shipwreck, 2) to examine the importance of the Novy Svet wreck in terms of Black Sea maritime trade in the Late Byzantine period, 3) to present the data collected at the Center for Underwater Archaeology at the Taras Shevchenko National University in Kiev, Ukraine (CUA) about the graffiti inscribed on the Günsenin IV amphorae raised from the Novy Svet wreck and 4) to discuss the meaning and importance of the graffiti, both aboard the ship itself and in a more general context. The thesis introduces the results of the 2002-2008 underwater excavation seasons at Novy Svet. Excavators have identified a 13th century shipwreck filled with glazed ceramics and amphorae as a Pisan vessel sunk on August 14, 1277. The majority of the amphorae are Günsenin IV jars and have graffiti inscribed on them. Analysis of the graffiti focuses on the division of the marks into morphological categories, and identifying parallels for the specific forms at other archaeological sites.