The Chora of Nymphaion (6Th Century BC-6Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medicinal Vessels from Tell Atrib (Egypt)

Études et Travaux XXX (2017), 315–337 Medicinal Vessels from Tell Atrib (Egypt) A Ł, A P Abstract: This article off ers publication of seventeen miniature vessels discovered in Hellenistic strata of Athribis (modern Tell Atrib) during excavations carried out by Polish- -Egyptian Mission in the 1980s/1990s. The vessels, made of clay, faience and bronze, are mostly imports from various areas within the Mediterranean, including Sicily and Lycia, and more rarely – local imitations of imported forms. Two vessels carry stamps with Greek inscriptions, indicating that they were containers for lykion, a medicine extracted from the plant of the same name, highly esteemed in antiquity. The vessels may be connected with a healing activity practised within the Hellenistic bath complex. Keywords: Tell Atrib, Hellenistic Egypt, pottery, medicinal vessels, lykion, healing activity Adam Łajtar, Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Warszawa; [email protected] Anna Południkiewicz, Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Warszawa; [email protected] Archaeological excavations carried out between 1985 and 1999 by a Polish-Egyptian Mission within the Hellenistic and Roman dwelling districts and industrial quarters of ancient Athribis (modern Tell Atrib), the capital of the tenth Lower Egyptian nome,1 yielded an interesting series of miniature vessels made of clay, faience and bronze.2 Identical or similar vessels are known from numerous sites within the Mediterranean and are considered as containers for medicines in a liquid form. A particularly rich collection of such vessels, amounting to 54 objects, was discovered in the 1950s, during work carried out by an American archaeological expedition in Morgantina 1 For a preliminary presentation of the results, see reports published in journal Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean (vols I–VII, by K. -

Karadeniz Teknik Üniversitesi * Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü

KARADENİZ TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ * SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS PROGRAMI ANTİK ÇAĞDA HERMONASSA LİMANI: SİYASİ VE EKONOMİK GELİŞMELER YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ Betül AKKAYA MAYIS-2018 TRABZON KARADENİZ TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ * SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS PROGRAMI ANTİK ÇAĞDA HERMONASSA LİMANI: SİYASİ VE EKONOMİK GELİŞMELER YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ Betül AKKAYA Tez Danışmanı: Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Osman EMİR MAYIS-2018 TRABZON ONAY Betül AKKAYA tarafından hazırlanan Antik Çağda Hermonassa Limanı: Siyasi ve Ekonomik Gelişmeler adlı bu çalışma 17.10.2018 tarihinde yapılan savunma sınavı sonucunda oy birliği/ oy çokluğu ile başarılı bulunarak jürimiz tarafından Tarih Anabilim Dalında Yüksek Lisans Tezi olarak kabul edilmiştir. Juri Üyesi Karar İmza Unvanı- Adı ve Soyadı Görevi Kabul Ret Prof. Dr. Mehmet COĞ Başkan Prof. Dr. Süleyman ÇİĞDEM Üye Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Osman EMİR Üye Yukarıdaki imzaların, adı geçen öğretim üyelerine ait olduklarını onaylarım. Prof. Dr. Yusuf SÜRMEN Enstitü Müdürü BİLDİRİM Tez içindeki bütün bilgilerin etik davranış ve akademik kurallar çerçevesinde elde edilerek sunulduğunu, ayrıca tez yazım kurallarına uygun olarak hazırlanan bu çalışmada orijinal olmayan her türlü kaynağa eksiksiz atıf yapıldığını, aksinin ortaya çıkması durumunda her tür yasal sonucu kabul ettiğimi beyan ediyorum. Betül AKKAYA 21.05.2018 ÖNSÖZ Kolonizasyon kelime anlamı olarak bir ülkenin başka bir ülke üzerinde ekonomik olarak egemenlik kurması anlamına gelmektedir. Koloni ise egemenlik kurulan toprakları ifade etmektedir. Antik çağlardan itibaren kolonizasyon hareketleri devam etmektedir. Greklerin Karadeniz üzerinde gerçekleştirdiği koloni faaliyetleri ışığında ele alınan Hermonassa antik kenti de Kuzey Karadeniz kıyılarında yer alan önemli bir Grek kolonisidir. Bugünkü Kırım sınırları içinde yer almış olan kent aynı zamanda Bosporus Krallığı içerisinde önemli bir merkez olarak var olmuştur. -

The Monopteros in the Athenian Agora

THE MONOPTEROS IN THE ATHENIAN AGORA (PLATE 88) O SCAR Broneerhas a monopterosat Ancient Isthmia. So do we at the Athenian Agora.' His is middle Roman in date with few architectural remains. So is ours. He, however, has coins which depict his building and he knows, from Pau- sanias, that it was built for the hero Palaimon.2 We, unfortunately, have no such coins and are not even certain of the function of our building. We must be content merely to label it a monopteros, a term defined by Vitruvius in The Ten Books on Architecture, IV, 8, 1: Fiunt autem aedes rotundae, e quibus caliaemonopteroe sine cella columnatae constituuntur.,aliae peripteroe dicuntur. The round building at the Athenian Agora was unearthed during excavations in 1936 to the west of the northern end of the Stoa of Attalos (Fig. 1). Further excavations were carried on in the campaigns of 1951-1954. The structure has been dated to the Antonine period, mid-second century after Christ,' and was apparently built some twenty years later than the large Hadrianic Basilica which was recently found to its north.4 The lifespan of the building was comparatively short in that it was demolished either during or soon after the Herulian invasion of A.D. 267.5 1 I want to thank Professor Homer A. Thompson for his interest, suggestions and generous help in doing this study and for his permission to publish the material from the Athenian Agora which is used in this article. Anastasia N. Dinsmoor helped greatly in correcting the manuscript and in the library work. -

Bosporos Studies 2001 2002 2003

BOSPOROS STUDIES 2001 Vol. I Vinokurov N.I. Acclimatization of vine and the initial period of the viticulture development in the Northern Black Sea Coast Gavrilov A. V, Kramarovsky M.G. The barrow near the village of Krinichky in the South-Eastern Crimea Petrova E.B. Menestratos and Sog (on the problem of King's official in Theodosia in the first centuries AD) Fedoseyev N.F. On the collection of ceramics stamps in Warsaw National Museum Maslennikov A.A. Rural settlements of European Bosporos (Some problems and results of research) Matkovskaya T.A. Men's costume of European Bosporos of the first centuries AD (materials of Kerch lapidarium) Sidorenko V.A. The highest military positions in Bosporos in the 2nd – the beginning of the 4th centuries (on the materials of epigraphies) Zin’ko V.N., Ponomarev L.Yu. Research of early medieval monuments in the neighborhood of Geroevskoye settlement Fleorov V.S. Burnished bowls, dishes, chalices and kubyshki of Khazar Kaghanate Gavrilov A.V. New finds of antique coins in the South-Eastern Crimea Zin’ko V.N. Bosporos City of Nymphaion and the Barbarians Illarioshkina E.N. Gods and heroes of Greek myths in Bosporos gypsum plastics Kulikov A.V. On the problem of the crisis of money circulation in Bosporos in the 3rd century ВС Petrova E.B. On cults of ancient Theodosia Ponomarev D.Yu. Paleopathogeography of kidney stone illness in the Crimea in ancient and Medieval epoch Magomedov B. Cherniakhovskaya culture and Bosporos Niezabitowska V. Collection of things from Kerch and Caucasus in Wroclaw Archaeology Museum 2002 Vol. -

A Comparative Study of Ancient Greek City Walls in North-Western Black Sea During the Classical and Hellenistic Times

INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES MA IN BLACK SEA CULTURAL STUDIES A comparative study of ancient Greek city walls in North-Western Black Sea during the Classical and Hellenistic times Thessaloniki, 2011 Supervisor’s name: Professor Akamatis Ioannis Student’s name: Fantsoudi Fotini Id number:2201100018 Abstract Greek presence in the North Western Black Sea Coast is a fact proven by literary texts, epigraphical data and extensive archaeological remains. The latter in particular are the most indicative for the presence of walls in the area and through their craftsmanship and techniques being used one can closely relate these defensive structures to the walls in Asia Minor and the Greek mainland. The area examined in this paper, lies from ancient Apollonia Pontica on the Bulgarian coast and clockwise to Kerch Peninsula.When establishing in these places, Greeks created emporeia which later on turned into powerful city states. However, in the early years of colonization no walls existed as Greeks were starting from zero and the construction of walls needed large funds. This seems to be one of the reasons for the absence of walls of the Archaic period to which lack comprehensive fieldwork must be added. This is also the reason why the Archaic period is not examined, but rather the Classical and Hellenistic until the Roman conquest. The aim of Greeks when situating the Black Sea was to permanently relocate and to become autonomous from their mother cities. In order to be so, colonizers had to create cities similar to their motherlands. More specifically, they had to build public buildings, among which walls in order to prevent themselves from the indigenous tribes lurking to chase away the strangers from their land. -

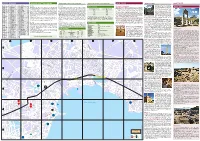

1 2 3 4 5 a B C D E

STREET REGISTER ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE Amurskaya E/F-2 Krasniy Spusk G-3 Radishcheva E-5 By Bus By Plane Great Mitridat Stairs C-4, near the Lenina Admirala Vladimirskogo E/F-3 Khersonskaya E/F-3 Rybatskiy prichal D/C-4-B-5 Churches & Cathedrals pl. The stairs were built in the 1930’s with plans Ancient Cities Admirala Azarova E-4/5 Katernaya E-3 Ryabova F-4 Arriving by bus is the only way to get to Kerch all year round. The bus station There is a local airport in Kerch, which caters to some local Crimean flights Ferry schedule Avdeyeva E-5 Korsunskaya E-3 Repina D-4/5 Church of St. John the Baptist C-4, Dimitrova per. 2, tel. (+380) 6561 from the Italian architect Alexander Digby. To save Karantinnaya E-3 Samoylenko B-3/4 itself is a buzzing place thanks to the incredible number of mini-buses arriving during the summer season, but the only regular flight connection to Kerch is you the bother we have already counted them; Antonenko E-5 From Kerch (from Port Krym) To Kerch (from Port Kavkaz) 222 93. This church is a unique example of Byzantine architecture. It was built in Admirala Fadeyeva A/B-4 Kommunisticheskaya E-3-F-5 Sladkova C-5 and departing. Marshrutkas run from here to all of the popular destinations in through Simferopol State International, which has regular flights to and from Kyiv, there are 432 steps in all meandering from the Dep. -

Great Waterworks in Roman Greece Aqueducts and Monumental Fountain Structures Function in Context

Great Waterworks in Roman Greece Aqueducts and Monumental Fountain Structures Function in Context Access edited by Open Georgia A. Aristodemou and Theodosios P. Tassios Archaeopress Archaeopress Roman Archaeology 35 © Archaeopress and the authors, 2017. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 764 7 ISBN 978 1 78491 765 4 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the authors 2018 Cover: The monumental arcade bridge of Moria,Access Lesvos, courtesy of Dr Yannis Kourtzellis Creative idea of Tasos Lekkas (Graphics and Web Designer, International Hellenic University) Open All rights Archaeopressreserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Oxuniprint, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com © Archaeopress and the authors, 2017. Contents Preface ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� iii Georgia A. Aristodemou and Theodosios P. Tassios Introduction I� Roman Aqueducts in Greece �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������1 Theodosios P. Tassios Introduction II� Roman Monumental Fountains (Nymphaea) in Greece �����������������������������������������10 Georgia A. Aristodemou PART I: AQUEDUCTS Vaulted-roof aqueduct channels in Roman -

Andrea F. Gatzke, Mithridates VI Eupator and Persian Kingship

The Ancient History Bulletin VOLUME THIRTY-THREE: 2019 NUMBERS 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson ò Michael Fronda òDavid Hollander Timothy Howe ò John Vanderspoel Pat Wheatley ò Sabine Müller òAlex McAuley Catalina Balmacedaò Charlotte Dunn ISSN 0835-3638 ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Volume 33 (2019) Numbers 1-2 Edited by: Edward Anson, Catalina Balmaceda, Michael Fronda, David Hollander, Alex McAuley, Sabine Müller, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Assistant Editor: Charlotte Dunn Editorial correspondents Elizabeth Baynham, Hugh Bowden, Franca Landucci Gattinoni, Alexander Meeus, Kurt Raaflaub, P.J. Rhodes, Robert Rollinger, Victor Alonso Troncoso Contents of volume thirty-three Numbers 1-2 1 Kathryn Waterfield, Penteconters and the Fleet of Polycrates 19 John Hyland, The Aftermath of Aigospotamoi and the Decline of Spartan Naval Power 42 W. P. Richardson, Dual Leadership in the League of Corinth and Antipater’s Phantom Hegemony 60 Andrea F. Gatzke, Mithridates VI Eupator and Persian Kingship NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS AND SUBSCRIBERS The Ancient History Bulletin was founded in 1987 by Waldemar Heckel, Brian Lavelle, and John Vanderspoel. The board of editorial correspondents consists of Elizabeth Baynham (University of Newcastle), Hugh Bowden (Kings College, London), Franca Landucci Gattinoni (Università Cattolica, Milan), Alexander Meeus (University of Mannhiem), Kurt Raaflaub (Brown University), P.J. Rhodes (Durham University), Robert Rollinger (Universität Innsbruck), Victor Alonso Troncoso (Universidade da Coruña) AHB is currently edited by: Timothy Howe (Senior Editor: [email protected]), Edward Anson, Catalina Balmaceda, Michael Fronda, David Hollander, Alex McAuley, Sabine Müller, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley and Charlotte Dunn. AHB promotes scholarly discussion in Ancient History and ancillary fields (such as epigraphy, papyrology, and numismatics) by publishing articles and notes on any aspect of the ancient world from the Near East to Late Antiquity. -

Crimea______9 3.1

CONTENTS Page Page 1. Introduction _____________________________________ 4 6. Transport complex ______________________________ 35 1.1. Brief description of the region ______________________ 4 1.2. Geographical location ____________________________ 5 7. Communications ________________________________ 38 1.3. Historical background ____________________________ 6 1.4. Natural resource potential _________________________ 7 8. Industry _______________________________________ 41 2. Strategic priorities of development __________________ 8 9. Energy sector ___________________________________ 44 3. Economic review 10. Construction sector _____________________________ 46 of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea ________________ 9 3.1. The main indicators of socio-economic development ____ 9 11. Education and science ___________________________ 48 3.2. Budget _______________________________________ 18 3.3. International cooperation _________________________ 20 12. Culture and cultural heritage protection ___________ 50 3.4. Investment activity _____________________________ 21 3.5. Monetary market _______________________________ 22 13. Public health care ______________________________ 52 3.6. Innovation development __________________________ 23 14. Regions of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea _____ 54 4. Health-resort and tourism complex_________________ 24 5. Agro-industrial complex __________________________ 29 5.1. Agriculture ____________________________________ 29 5.2. Food industry __________________________________ 31 5.3. Land resources _________________________________ -

History of Phanagoria

Ассоциация исследователей ИНСТИТУТ АРХЕОЛОГИИ РАН ФАНАГОРИЙСКАЯ ЭКСПЕДИЦИЯ ИА РАН PHANAGORIA EDITED BY V.D. KUZNETSOV Moscow 2016 904(470.62) 63.443.22(235.73) Утверждено к печати Ученым советом Института археологии РАН Edited by V.D. Kuznetsov Text: Abramzon M.G., PhD, Professor, Magnitogorsk State Technical University Voroshilov A.N., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Voroshilova O.N., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Garbuzov G.P., PhD, Southern Scientific Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Rostov-on-Don) Golofast L.A., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Gunchina O.L., conservator-restorer, Phanagoria Museum-Preserve Dobrovolskaya E.V., PhD, A.N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences Dobrovolskaya M.V., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Zhukovsky M.O., Deputy Director of the Phanagoria Museum-Preserve Zavoikin A.A., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Zavoikina N.V., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Kokunko G.V., Historical and Cultural Heritage of Kuban Program Coordinator Kuznetsov V.D., PhD, Director of the Phanagoria Museum-Preserve, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Kuzmina (Shorunova) Yu.N., PhD, Curator of the Phanagoria Museum-Preserve, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Olkhovsky S.V., Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Pavlichenko N.A., PhD, Institute of History, Russian Academy of Sciences Saprykina I.A., PhD, Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences Published with financial support from the Volnoe Delo Oleg Deripaska Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission of the copyright owners. -

Persian Imperial Policy Behind the Rise and Fall of the Cimmerian Bosporus in the Last Quarter of the Sixth to the Beginning of the Fifth Century BC

Persian Imperial Policy Behind the Rise and Fall of the Cimmerian Bosporus in the Last Quarter of the Sixth to the Beginning of the Fifth Century BC Jens Nieling The aim of the following paper is to recollect arguments for the hypotheses of a substantial Persian interference in the Greek colonies of the Cimmerian Bosporus and that they remained not untouched by Achaemenid policy in western Anatolia. The settlements ought to have been affected positively in their prime in the last quarter of the sixth century, but also harmed during their first major crisis at the beginning of the fifth century and afterwards. A serious break in the tight interrelationship between the Bosporan area and Achaemenid Anatolia occurred through the replacement of the Archaeanactid dynasty, ruling the Cimmerian Bosporus from 480 onwards, in favour of the succeeding Spartocids by an Athenian naval expedition under the command of Pericles in the year 438/437.1 The assumption of a predominant Persian influence to the north of the Caucasus mountains contradicts the still current theory of V. Tolstikov2 and the late Yu.G. Vinogradov,3 who favour instead a major Scythian or local impact as a decisive factor at the Bosporan sites.4 To challenge this traditional posi- tion, this paper will follow the successive stages of architectural development in the central settlement of Pantikapaion on its way to becoming the capital of the region. The argumentation is necessarily based on a parallelization of stratigraphical evidence with historical sources, since decisive archaeological data to support either the Persian or the Scythian hypothesis are few. -

Domestic Architecture in the Greek Colonies of the Black Sea from the Archaic Period Until the Late Hellenictic Years Master’S Dissertation

DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE IN THE GREEK COLONIES OF THE BLACK SEA FROM THE ARCHAIC PERIOD UNTIL THE LATE HELLENICTIC YEARS MASTER’S DISSERTATION STUDENT: KALLIOPI KALOSTANOU ID: 2201140014 SUPERVISOR: PROF. MANOLIS MANOLEDAKIS THESSALONIKI 2015 INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY MASTER’S DISSERTATION: DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE IN THE GREEK COLONIES OF THE BLACK SEA FROM THE ARCHAIC PERIOD UNTIL THE LATE HELLENISTIC YEARS KALLIOPI KALOSTANOU THESSALONIKI 2015 [1] CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 4 ARCHAIC PERIOD 1.1. EARLY (610-575 BC) & MIDDLE ARCHAIC PERIOD (575-530 BC): ARCHITECTURE OF DUGOUTS AND SEMI DUGOUTS .................................................................................... 8 1.1. 1. DUGOUTS AND SEMI-DUGOUTS: DWELLINGS OR BASEMENTS? .................... 20 1.1. 2. DUGOUTS: LOCAL OR GREEK IVENTIONS? ........................................................... 23 1.1. 3. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................. 25 1.2. LATE ARCHAIC PERIOD (530-490/80 BC): ABOVE-GROUND HOUSES .................. 27 1.2.1 DEVELOPMENT OF THE ABOVE-GROUND HOUSES .............................................. 30 1.2.2. CONCLUSION: ............................................................................................................. 38 CLASSICAL PERIOD 2.1. EARLY CLASSICAL PERIOD (490/80-450 BC): ............................................................ 43