Medicinal Vessels from Tell Atrib (Egypt)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Study of Ancient Greek City Walls in North-Western Black Sea During the Classical and Hellenistic Times

INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES MA IN BLACK SEA CULTURAL STUDIES A comparative study of ancient Greek city walls in North-Western Black Sea during the Classical and Hellenistic times Thessaloniki, 2011 Supervisor’s name: Professor Akamatis Ioannis Student’s name: Fantsoudi Fotini Id number:2201100018 Abstract Greek presence in the North Western Black Sea Coast is a fact proven by literary texts, epigraphical data and extensive archaeological remains. The latter in particular are the most indicative for the presence of walls in the area and through their craftsmanship and techniques being used one can closely relate these defensive structures to the walls in Asia Minor and the Greek mainland. The area examined in this paper, lies from ancient Apollonia Pontica on the Bulgarian coast and clockwise to Kerch Peninsula.When establishing in these places, Greeks created emporeia which later on turned into powerful city states. However, in the early years of colonization no walls existed as Greeks were starting from zero and the construction of walls needed large funds. This seems to be one of the reasons for the absence of walls of the Archaic period to which lack comprehensive fieldwork must be added. This is also the reason why the Archaic period is not examined, but rather the Classical and Hellenistic until the Roman conquest. The aim of Greeks when situating the Black Sea was to permanently relocate and to become autonomous from their mother cities. In order to be so, colonizers had to create cities similar to their motherlands. More specifically, they had to build public buildings, among which walls in order to prevent themselves from the indigenous tribes lurking to chase away the strangers from their land. -

1 2 3 4 5 a B C D E

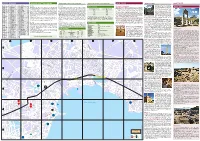

STREET REGISTER ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE Amurskaya E/F-2 Krasniy Spusk G-3 Radishcheva E-5 By Bus By Plane Great Mitridat Stairs C-4, near the Lenina Admirala Vladimirskogo E/F-3 Khersonskaya E/F-3 Rybatskiy prichal D/C-4-B-5 Churches & Cathedrals pl. The stairs were built in the 1930’s with plans Ancient Cities Admirala Azarova E-4/5 Katernaya E-3 Ryabova F-4 Arriving by bus is the only way to get to Kerch all year round. The bus station There is a local airport in Kerch, which caters to some local Crimean flights Ferry schedule Avdeyeva E-5 Korsunskaya E-3 Repina D-4/5 Church of St. John the Baptist C-4, Dimitrova per. 2, tel. (+380) 6561 from the Italian architect Alexander Digby. To save Karantinnaya E-3 Samoylenko B-3/4 itself is a buzzing place thanks to the incredible number of mini-buses arriving during the summer season, but the only regular flight connection to Kerch is you the bother we have already counted them; Antonenko E-5 From Kerch (from Port Krym) To Kerch (from Port Kavkaz) 222 93. This church is a unique example of Byzantine architecture. It was built in Admirala Fadeyeva A/B-4 Kommunisticheskaya E-3-F-5 Sladkova C-5 and departing. Marshrutkas run from here to all of the popular destinations in through Simferopol State International, which has regular flights to and from Kyiv, there are 432 steps in all meandering from the Dep. -

The Chora of Nymphaion (6Th Century BC-6Th Century

The Chora of Nymphaion (6th century BC-6th century AD) Viktor N. Zin’ko The exploration of the rural areas of the European Bosporos has gained in scope over the last decades. Earlier scholars focused on studying particular archaeological sites and an overall reconstruction of the rural territories of the Bosporan poleis as well as on a general understanding of the polis-chora relationship.1 These works did not aim at an in-depth study of the chora of any one particular city-state limited as they were to small-scale excavations of individual settlements. In 1989, the author launched a comprehensive research project on the chora of Nymphaion. A careful examination of archive materials and the results of the surveys revealed an extensive number of previously unknown archaeological sites. The limits of Nymphaion’s rural territory corresponded to natural bor- der-lines (gullies, steep slopes of ridges etc.) impassable to the Barbarian cav- alry. The region has better soils than the rest of the peninsula, namely dark chestnut černozems,2 and the average level of precipitation is 100 mm higher than in other areas.3 The core of the territory was represented by fertile lands, Fig. 1. Map of the Kimmerian Bosporos (hatched – chora of Nymphaion in the 5th century BC; cross‑hatched – chora of Nymphaion in the 4th‑early 3rd centuries BC). 20 Viktor N. Zin’ko stretching from the littoral inland, and bounded to the north and south by two ravines situated 7 km apart. The two ravines originally began at the western extremities of the ancient estuaries (now the Tobečik and Čurubaš Lakes). -

Ancient Fishing and Fish Processing in the Black Sea Region

BLACK SEA STUDIES 2 The Danish National Research Foundation’s Centre for Black Sea Studies ANCIENT FISHING AND FISH PROCESSING IN THE BLACK SEA REGION Edited by Tønnes Bekker-Nielsen AARHUS UNIVERSITY PRESS ANCIENT FISHING AND FISH PROCESSING IN THE BLACK SEA REGION Proceedings of an interdisciplinary workshop on marine resources and trade in fish products in the Black Sea region in antiquity, University of Southern Denmark, Esbjerg, April 4-5, 2003. Copyright: Aarhus University Press, 2005 Cover design by Jakob Munk Højte and Lotte Bruun Rasmussen Mosaic with scene of fishermen at sea from a tomb in the catacomb of Hermes in Hadrumetum (Sousse Museum, inv.no. 10.455). Late second century AD. 320 x 280 cm. Photo: Gilles Mermet. Printed in Gylling by Narayana Press ISBN 87 7934 096 2 AARHUS UNIVERSITY PRESS Langelandsgade 177 DK-8200 Aarhus N 73 Lime Walk Headington, Oxford OX2 7AD Box 511 Oakville, CT 06779 www.unipress.au.dk The publication of this volume has been made possible by a generous grant from the Danish National Research Foundation Danish National Research Foundation’s Centre for Black Sea Studies Building 328 University of Aarhus DK-8000 Aarhus C www.pontos.dk Contents Illustrations and Tables 7 Introduction 13 Tønnes Bekker-Nielsen Fish as a Source of Food in Antiquity 21 John Wilkins Sources for Production and Trade of Greek and Roman Processed Fish 31 Robert I. Curtis The Archaeological Evidence for Fish Processing in the Western Mediterranean 47 Athena Trakadas The Technology and Productivity of Ancient Sea Fishing 83 Tønnes Bekker-Nielsen The Reliability of Fishing Statistics as a Source for Catches and Fish Stocks in Antiquity 97 Anne Lif Lund Jacobsen Fishery in the Life of the Nomadic Population of the Northern Black Sea Area in the Early Iron Age 105 Nadežda A. -

Les Carnets De L'acost, 13

Les Carnets de l’ACoSt Association for Coroplastic Studies 13 | 2015 Varia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/acost/566 DOI: 10.4000/acost.566 ISSN: 2431-8574 Publisher ACoSt Printed version Date of publication: 5 August 2015 Electronic reference Les Carnets de l’ACoSt, 13 | 2015 [Online], Online since 17 August 2015, connection on 23 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/acost/566 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/acost.566 This text was automatically generated on 23 September 2020. Les Carnets de l'ACoSt est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Editorial Oliver Pilz Coroplastic Studies and the History of Religion: Figurines in Yehud and the Interdisciplinary Nature of the Study of Terracottas Izaak J. de Hulster Ein Affe spielt Tragödie. Zum Problem der Tiermaske bei vermeintlichen und tatsächlichen Schauspielerstatuetten Simone Voegtle Bust Thymiateria from Olbia Pontike Tetiana M. Shevchenko Les terres cuites figurées du sanctuaire de Kirrha (Delphes) : Bilan des premières recherches Stéphanie Huysecom-Haxhi Chroniques Entre la Mésopotamie et l’Indus. Réflexions sur les figurines de terre cuite d’Asie Centrale aux 4e et 3e millénaires Annie Caubet Painted Gallo-Roman Figurines in Vendeuil-Caply Adrien Bossard Travaux en cours A Catalogue of the Greek and Roman Terracottas in the Aydın Archaeological Museum Murat Çekіlmez A Survey of Terracotta Figurines from Domestic Contexts in South Italy in the 6th and 5th Centuries B.C.E. Aura Piccioni Two Collaborative Projects for Coroplastic Research, II. -

The Cities That Never Were. Failed Attempts at Colonization in the Black Sea

The Cities that Never Were. Failed Attempts at Colonization in the Black Sea Jakob Munk Højte Introduction The title of this paper is taken from a book that appeared a few years ago, The Land That Never Was, about one of the most spectacular frauds in history.1 In the year 1823 a group of Scots set out to the small but supposedly well run Territory of Poyais on the Mosquito Coast, in what is now Honduras. Here they had bought or commissioned land from a certain Sir Gregor McGregor, Cazique of Poyais, who had made the venture credible by having produced a brochure and a 350-page guide to the prosperous town with its many profit- able plantations and blossoming commerce.2 Upon arrival after crossing the Atlantic during the winter, the new settlers found nothing there – absolutely nothing, except a few huts occupied by natives. Few of the unfortunate colo- nists survived the first year in their new home. There may have been similar attempts in Antiquity at overselling the idea of going away to the Black Sea to settle. What interests me here, however, is the fact that not all attempts at founding colonies ended in success, neither in the early 19th century nor in Antiquity. The initial settlers of a new colony almost always found themselves in a very precarious situation and many factors contributed to the viability of the new apoikia. This paper intends to explore how the Greek-barbarian relationship affected the outcome of the co- lonial encounter at a macro level; how, to my mind, they were an important element in determining the Greek settlement pattern in the Black Sea region and possibly vice versa: what the particular settlement patterns, we can ob- serve in the region, might reveal about the nature of these relations. -

K Handmade Pottery

K Handmade pottery Nadežda A. Gavriljuk For a long time it has been believed that those people belonging to the so-called “barbarian world” surrounding ancient Greek towns were the manufacturers and users of handmade pottery. Finds of recent years, however, allow us to propose that this statement is only partly correct. In order to establish a fresh approach to the study of the interrelations between the local and Greek populations of the ancient centres of the northern Black Sea littoral, it is necessary to analyse the archaeological materials from each of these centres. Only interdisciplinary studies of pottery assemblages in their entirety (handmade, wheelmade tableware, cookingware, containers) will enable us to arrive at grounded conclusions as to the use and production of each particular group of pottery, the ratio between the barbarian and Greek components in the material culture of the Greeks of the northern Black Sea region and the history of each Greek polis. The evidence from Olbia, an exemplary site for the study of antiquity in the northern Black Sea littoral, is, in this aspect, of special importance. research history The handmade pottery of Olbia was first considered as a separate find category by T.N. Knipovič.733 Simultaneously, an attempt was made to apply chemical and technological analyses to studies of Olbian pottery,734 and the hypothesis was proposed that a proportion of the handmade pottery belonged to the indigenous population. A differing view about the pottery assemblages of ancient sites was held by V.V. Lapin. Based on the study of handmade pottery from Berezan’ and its comparison with the evidence from other Greek sites including Olynthos, he proposed that the handmade pottery from Berezan’ belonged to the material culture of the Greek population. -

Ifeiii Fev'l Psl Lire Mw :V.R'a*R>T'{»J • Yjj .''Xi.'L"?' KS»I !'Flv''s5iwjr «

ipf ;•»>•.;: i.iS •. i'• - * '. ff!*'.,''!' ''-r •' "i:> \/P~ei_ ho\4er_ 0639- ">j,: \r\> .'. \ *• 1 i'i Li's \ • • >; fr>". •/i ';nf VjiO * 3?j,<?i 'SC^b: '[''-i Ifeiii feV'l PSl lire mW :v.r'A*r>t'{»J • yJj .''Xi.'l"?' KS»i !'fLV''s5iWjR « 5SS'<";iSB»ra'..-,sJi L'J //. 5. huocl'^t^ '4. 5.€4 .1^ Lb ^ .of 12 .XII.61 CATALOGUE 1 \ oV PI* 1 i exj; Miletos. Single "barrel" preserved of top of double-barrelled handle; fragment seen by V.G. in October 1959. A See under A A- PI. 1 (^club 3 ex.: Alexandria. -A^o9\. PI. 1 1 ex.: Athens. Context of first half, perhaps first quarter, of 2nd century B.C. for this handle, SS 9382 from cistern B 20 : 2. club "5. q •SO ex. from four dies: Kos, Athens, 6; A±RXKSJixiJK:(xifi:;^x Delos, ^ fl 2 impressions on a single handle); Alexandria, iO« I Context of early 2nd century B.C. or earlier for SS 554 and 12682 from gSBF; of first half of 2nd century or earlier for SS 6619 from cistern E 6 : 2 PreTious publication: Meroutsos 1874, p.457, no.l (EM 89, from colleeti ou p .£?:2- <liu '.iin\X do't.,aio nmtorole aoln''' stampibito. Do altfJl si B ^ Gr'aK"^ f ci si ?, *'iauii 51 (d i?i (^xpoitii viniinlo nu mim^^ arnioro simple, fara iiici nii sonm ])e olC' 2. STAMPILI-; iNTlUCGri't-; ^1 STAM1MI.I-; j^j-pd-SCIPHAHIL}. 71 o 'ASaiou lAAAlor - Ip'dtp(,'zitnV'^^^^ fara alta "I'Ucatio I fNTOCMAlM. -

Settlements and Necropoleis of the Black Sea and Its Hinterland in Antiquity

Settlements and Necropoleis of the Black Sea and its Hinterland in Antiquity Select papers from the third international conference ‘The Black Sea in Antiquity and Tekkeköy: An Ancient Settlement on the Southern Black Sea Coast’, 27-29 October 2017, Tekkeköy, Samsun edited by Gocha R. Tsetskhladze and Sümer Atasoy with the collaboration of Akın Temür and Davut Yiğitpaşa Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-206-8 ISBN 978-1-78969-207-5 (e-Pdf) © Authors and Archaeopress 2019 Cover: Sebastopolis, Roman baths. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Oxuniprint, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Preface ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ iii List of Figures and Tables ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� iv Once again about the Establishment Date of Some Greek Colonies around the Black Sea ������������������������������������1 Gocha R� Tsetskhladze The Black Sea on the Tabula Peutingeriana �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������42 -

What Did Ancient Greeks Mean by the ‘Cimmerian Bosporus’?

doi: 10.2143/AWE.13.0.3038729 AWE 13 (2014) 29-48 WHAT DID ANCIENT GREEKS MEAN BY THE ‘CIMMERIAN BOSPORUS’? NATALIA GOUROVA Abstract The word ‘Bosporus’ in ‘Cimmerian Bosporus’ is usually perceived as the name for a unified state. However, this word was also used by ancient authors as a hydronym, for the strait between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov/Lake Maeotis and for denoting a specific territorial unit, as well as an alternate name for Panticapaeum. The use of Bosporus in written sources from the Archaic period to late antiquity followed a certain chronological sequence, which generally coincides with the periods of formation and transformation of the Bosporan state. Despite the interest of contemporary research in terminological interpretation and reinterpretation, we still take for granted some of the names used by ancient authors for denoting space and political entities. The meaning of these names, however, is not always clear, not only because of its possible multiplicity, but also because their meaning depends on the person who uses these names, on the specific circumstances of their use, on the historical context and the traditional vocabulary of the relevant period, as well as on their transformation over time. Moreover, the shift from the geographical meaning to the geopolitical one is often not easily identifiable. Additionally, as the interior structure of any political formation, with its different kinds of power, is also changeable through time, any reference to it requires a clarification with regards to the period in which each political entity existed. To provide a contemporary example: when talking about Russia, one can mean the Russian empire, or the Russian SFSR, part of the Soviet Union, or the contemporary Russian Federation. -

This Work Is Licensed Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. SOIL ZOOLOGY, THEN AND NOW - MOSTLY THEN D. Keith McE. Kevan Department of Entomology and Lyman Entomological Museum and Research Laboratory Macdonald College Campus, McGill University 21, 111 Lakeshore Road Ste-Anne de Bellevue, Que. H9X ICO CANADA Quaestiones Entomologicae 21:371.7-472 1985 ABSTRACT Knowledge of the animals that inhabit soil remained fragmentary and virtually restricted to a few conspicuous species until the latter part of the 19th Century, despite the publication, in 1549, of the first attempt at a thesis on the subject by Georg Bauer (Agricola). Even the writings of far-seeing naturalists, like White in 1789, and Darwin in 1840, did not arouse interest in the field. It was probably P.E. Midler in 1879, who first drew particular attention to the importance of invertebrate animals generally in humus formation. Darwin's book on earthworms, and the "formation of vegetable mould", published in 1881, and Drummond's suggestions, in 1887, regarding an analgous role for termites were landmarks, but, with the exception of a few workers, like Berlese and Diem at the turn of the century, little attention was paid to other animals in the soil, save incidentally to other investigations. Russell's famous Soil Conditions and Plant Growth could say little about the soil fauna other than earthworms. -

The Formation of a Russian Science of Classical Antiquities of Southern Russia in the 18Th and Early 19Th Century1

The Formation of a Russian Science of Classical Antiquities of Southern Russia in the 18th and early 19th century1 Irina V. Tunkina “Those who believe science begins with them do not understand science” (M.P. Pogodin, 1869) It is my firm belief, that studies of the history of science are possible only on the basis of a wide and detailed analysis of its authentic facts: this is incon- ceivable without proper consideration of the archival heritage of our prede- cessors. Without an examination and a critical analysis of various archive material, it is altogether impossible to write the history of any science at the level which scholarship has reached at the beginning of the third millenni- um. Most Russian archaeologists have paid little attention to, or have even completely disregarded, the history of their science, as demonstrated by the fact that no monograph about the foundation and activities of the central state body of pre-revolutionary Russian archaeology – the Archaeological Commission (1859-1919) has yet been published. There are still many gaps in our knowledge of the scientific heritage of Russian Classical studies. Quite a number of scholars whose field of study was the northern Black Sea region in Antiquity have simply been forgotten by modern archaeologists and thus deleted from the historical memory. Working from an investigation of the extensive archive materials, scientific literature and social-political periodicals of the 18th to the middle of the 19th centuries, I will attempt to present a general account of the establishment of the Russian school of Greek and Roman archaeology, epigraphy and numismatics of the northern Black Sea.2 The first stage of acquaintance with antiquities from the northern Black Sea region The early period (1725-1802) was in fact concerned exclusively with the activities of the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences (founded in 1724) and those of the travellers with inquiring minds so characteristic of the Age of Enlightenment.