The Cities That Never Were. Failed Attempts at Colonization in the Black Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medicinal Vessels from Tell Atrib (Egypt)

Études et Travaux XXX (2017), 315–337 Medicinal Vessels from Tell Atrib (Egypt) A Ł, A P Abstract: This article off ers publication of seventeen miniature vessels discovered in Hellenistic strata of Athribis (modern Tell Atrib) during excavations carried out by Polish- -Egyptian Mission in the 1980s/1990s. The vessels, made of clay, faience and bronze, are mostly imports from various areas within the Mediterranean, including Sicily and Lycia, and more rarely – local imitations of imported forms. Two vessels carry stamps with Greek inscriptions, indicating that they were containers for lykion, a medicine extracted from the plant of the same name, highly esteemed in antiquity. The vessels may be connected with a healing activity practised within the Hellenistic bath complex. Keywords: Tell Atrib, Hellenistic Egypt, pottery, medicinal vessels, lykion, healing activity Adam Łajtar, Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Warszawa; [email protected] Anna Południkiewicz, Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Warszawa; [email protected] Archaeological excavations carried out between 1985 and 1999 by a Polish-Egyptian Mission within the Hellenistic and Roman dwelling districts and industrial quarters of ancient Athribis (modern Tell Atrib), the capital of the tenth Lower Egyptian nome,1 yielded an interesting series of miniature vessels made of clay, faience and bronze.2 Identical or similar vessels are known from numerous sites within the Mediterranean and are considered as containers for medicines in a liquid form. A particularly rich collection of such vessels, amounting to 54 objects, was discovered in the 1950s, during work carried out by an American archaeological expedition in Morgantina 1 For a preliminary presentation of the results, see reports published in journal Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean (vols I–VII, by K. -

Iranians and Greeks in South Russia (Ancient History and Archaeology)

%- IRANIANS & GREEKS IN SOUTH RUSSIA BY M- ROSTOVTZEFF, Hon. D.Litt. PROFESSOR IN THE UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN MEMBER OF THE RUSSIAN ACAPEMY OF SCIENCE I i *&&* OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1922 Oxford University Press London Edinburgh Glasgow Copenhagen Nets York Toronto Melbourne Cape T&tm Bombay Calcutta Madras Shanghai Humphrey Milford Publisher to the University PREFACE THIS book is not intended to compete with the valuable and learned book of Ellis H. Minns on the same subject. Our aims are different. Minns endeavoured to give a complete survey of the material illustrating the early history of South Russia and of the views expressed by both Russian and non-Russian scholars on the many and various questions suggested by the study of that material. I do not mean that Minns' book is a mere compendium. In dealing with the various problems of the history and archaeology of South Russia Minns went his own way ; his criticism is acute, his views independent. Nevertheless his main object was to give a survey as full and as complete as possible. And his attempt was success- ful. Minns* book will remain for decades the chief source of informa- tion about South Russia both for Russian and for non- Russian scholars. My own aim is different. In my short exposition I have tried to give a history of the South Russian lands in the prehistoric, the proto- historic, and the classic periods down to the epoch of the migrations. By history I mean not a repetition of the scanty evidence preserved by the classical writers and illustrated by the archaeological material but an attempt to define the part played by South Russia in the history of the world in general, and to emphasize the contributions of South Russia to the civilization of mankind. -

Anatolian Rivers Between East and West

Anatolian Rivers between East and West: Axes and Frontiers Geographical, economical and cultural aspects of the human-environment interactions between the Kızılırmak and Tigris Rivers in ancient times A series of three Workshops * First Workshop The Connectivity of Rivers Bilkent University Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture & Faculty of Humanities and Letters Ankara 18th November 2016 ABSTRACTS Second Workshop, 4th – 7th May 2017, at the State University Shota Rustaveli, Batumi. The Exploitation of the Economic Resources of Rivers. Third Workshop, 28th – October 1st September 2017, at the French Institute for Anatolian Studies, Istanbul. The Cultural Aspects of Rivers. Frontier Rivers between Asia and Europe Anca Dan (Paris, CNRS-ENS, [email protected]) The concept of « frontier », the water resources and the extension of Europe/Asia are currently topics of debates to which ancient historians and archaeologists can bring their contribution. The aim of this paper is to draw attention to the watercourses which played a part in the mental construction of the inhabited world, in its division between West and East and, more precisely, between Europe and Asia. The paper is organized in three parts: the first is an inventory of the watercourses which have been considered, at some point in history, as dividing lines between Europe and Asia; the second part is an attempt to explain the need of dividing the inhabited world by streams; the third part assesses the impact of this mental construct on the reality of a river, which is normally at the same time an obstacle and a spine in the mental organization of a space. -

A Comparative Study of Ancient Greek City Walls in North-Western Black Sea During the Classical and Hellenistic Times

INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES MA IN BLACK SEA CULTURAL STUDIES A comparative study of ancient Greek city walls in North-Western Black Sea during the Classical and Hellenistic times Thessaloniki, 2011 Supervisor’s name: Professor Akamatis Ioannis Student’s name: Fantsoudi Fotini Id number:2201100018 Abstract Greek presence in the North Western Black Sea Coast is a fact proven by literary texts, epigraphical data and extensive archaeological remains. The latter in particular are the most indicative for the presence of walls in the area and through their craftsmanship and techniques being used one can closely relate these defensive structures to the walls in Asia Minor and the Greek mainland. The area examined in this paper, lies from ancient Apollonia Pontica on the Bulgarian coast and clockwise to Kerch Peninsula.When establishing in these places, Greeks created emporeia which later on turned into powerful city states. However, in the early years of colonization no walls existed as Greeks were starting from zero and the construction of walls needed large funds. This seems to be one of the reasons for the absence of walls of the Archaic period to which lack comprehensive fieldwork must be added. This is also the reason why the Archaic period is not examined, but rather the Classical and Hellenistic until the Roman conquest. The aim of Greeks when situating the Black Sea was to permanently relocate and to become autonomous from their mother cities. In order to be so, colonizers had to create cities similar to their motherlands. More specifically, they had to build public buildings, among which walls in order to prevent themselves from the indigenous tribes lurking to chase away the strangers from their land. -

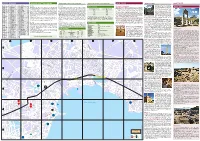

1 2 3 4 5 a B C D E

STREET REGISTER ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE Amurskaya E/F-2 Krasniy Spusk G-3 Radishcheva E-5 By Bus By Plane Great Mitridat Stairs C-4, near the Lenina Admirala Vladimirskogo E/F-3 Khersonskaya E/F-3 Rybatskiy prichal D/C-4-B-5 Churches & Cathedrals pl. The stairs were built in the 1930’s with plans Ancient Cities Admirala Azarova E-4/5 Katernaya E-3 Ryabova F-4 Arriving by bus is the only way to get to Kerch all year round. The bus station There is a local airport in Kerch, which caters to some local Crimean flights Ferry schedule Avdeyeva E-5 Korsunskaya E-3 Repina D-4/5 Church of St. John the Baptist C-4, Dimitrova per. 2, tel. (+380) 6561 from the Italian architect Alexander Digby. To save Karantinnaya E-3 Samoylenko B-3/4 itself is a buzzing place thanks to the incredible number of mini-buses arriving during the summer season, but the only regular flight connection to Kerch is you the bother we have already counted them; Antonenko E-5 From Kerch (from Port Krym) To Kerch (from Port Kavkaz) 222 93. This church is a unique example of Byzantine architecture. It was built in Admirala Fadeyeva A/B-4 Kommunisticheskaya E-3-F-5 Sladkova C-5 and departing. Marshrutkas run from here to all of the popular destinations in through Simferopol State International, which has regular flights to and from Kyiv, there are 432 steps in all meandering from the Dep. -

The Chora of Nymphaion (6Th Century BC-6Th Century

The Chora of Nymphaion (6th century BC-6th century AD) Viktor N. Zin’ko The exploration of the rural areas of the European Bosporos has gained in scope over the last decades. Earlier scholars focused on studying particular archaeological sites and an overall reconstruction of the rural territories of the Bosporan poleis as well as on a general understanding of the polis-chora relationship.1 These works did not aim at an in-depth study of the chora of any one particular city-state limited as they were to small-scale excavations of individual settlements. In 1989, the author launched a comprehensive research project on the chora of Nymphaion. A careful examination of archive materials and the results of the surveys revealed an extensive number of previously unknown archaeological sites. The limits of Nymphaion’s rural territory corresponded to natural bor- der-lines (gullies, steep slopes of ridges etc.) impassable to the Barbarian cav- alry. The region has better soils than the rest of the peninsula, namely dark chestnut černozems,2 and the average level of precipitation is 100 mm higher than in other areas.3 The core of the territory was represented by fertile lands, Fig. 1. Map of the Kimmerian Bosporos (hatched – chora of Nymphaion in the 5th century BC; cross‑hatched – chora of Nymphaion in the 4th‑early 3rd centuries BC). 20 Viktor N. Zin’ko stretching from the littoral inland, and bounded to the north and south by two ravines situated 7 km apart. The two ravines originally began at the western extremities of the ancient estuaries (now the Tobečik and Čurubaš Lakes). -

Aparchai and Phoroi: a New Commented Edition of the Athenian

Thèse de doctorat présentée à la Faculté des Lettres de l'Université de Fribourg (Suisse) Aparchai and Phoroi A New Commented Edition of the Athenian Tribute Quota Lists and Assessment Decrees Part I : Text Björn Paarmann (Danemark) 2007 Contents Preface 3 Introduction 7 Research History 16 The Tribute Lists as a Historical Source 37 Chapter 1. The Purpose of the Tribute Lists 40 1.1 The Tribute Quota Lists 40 1.1.1 Archives or Symbols? 40 1.1.2 Archives? 40 1.1.2 Accounts? 42 1.1.3 Votives? 43 1.1.4 Conclusion 50 1.2 The Assessment Decrees 52 1.3. Conclusion: Θεοί and θεδι 53 Chapter 2. The Geographical Distribution of the Ethnics 55 2.1 The Organisation of the Quota Lists 55 2.2 The Interpretation of the Data 58 2.3 Conclusion 63 Chapter 3. Tribute Amount and the Size of the Pokis 64 3.1 Tribute Amount and Surface Area 64 3.2 Examination of the Evidence 73 3.3 Conclusion 77 Chapter 4. Ethnics and Toponyms in the Tribute Lists 78 Conclusion: On the Shoulders of Giants 87 Future Perspectives 91 Appendix: Size of the Members of the Delian League 92 Bibliography 97 Plates 126 Preface A new edition of the tribute quota lists and assessment decrees needs, if not an excuse, then perhaps at least an explanation. Considering the primary importance of these historical sources, it is astonishing how little attention has been paid to the way they have been edited by Meritt, McGregor and Wade-Gery in The Athenian Tnbute Lists (ATL) I-IV from 1939-1953 and by Meritt in Inscnptiones Graecae (IG I3) 254-291 from 1981 during the last several decades.1 This negligence on the part of contemporary scholars, both ancient historians and, more surprisingly, also Greek epigraphists, stands in sharp contrast to the central place the lists take in academic articles, monographs and history books dealing with Greek history of the fifth century BC. -

Ancient Greek Colonies in the Black Sea

Contents Volume I Dionysopolis, its territory and neighbours in the pre-Roman times • 1 Margarit Damyanov Bizone • • 37 Asen Emilov Salkin La Thrace Pontique et la mythologie Grecque ••• • 51 Zlatozara Gotcheva Burial and post-burial rites in the necropoleis of the Greek colonies on the Bulgarian Black Sea Littoral • • 85 Krystina Panayotova Le monnayage de Messambria et les Monnayages d'Apollonia, Odessos et Dionysopolis 127 Ivan Karayotov Durankulak - a Territorium Sacrum of the Goddess Cybele 175 Henrieta Todorova Kallatis 239 Alexandru Avram Tornis 287 Livia Buzoianu and Maria Bârbulescu Nécropoles Grecques du Pont Gauche: Istros, Orgamé, Tomis, Callatis 337 Vasilica Lungu «L'histoire par les noms» dans les villes Grecques de Scythie et Scythie Mineure aux Vf-Ier Siècles av. S.-C 383 Victor Cojocaru Tyras: The Greek City on the River Tyras 435 Tatyana Lvovna Samoylova The Ancient City of Nikonion 471 Natalya Mikhaylovna Sekerskaya Greek Settlements on the Shores of the Bay of Odessa and Adjacent Estuaries 507 Yevgen iya Fyodorovna Redina Achilles on the Island of Leuke 537 Sergey Borisovitch Okhotnikov andAnatoliy Stepanovitch Ostroverkhov Lower Dnieper Hillforts and the Influence of Greek Culture (2nd Century BC - 2nd Century AD) 563 Nadezhda Avksentyevna Gavrilyuk and Valentina Vladimirovna Krapivina Olbia Pontica in the 3rd-4th Centuries AD 591 Valentina Vladimirovna Krapivina Greek Imports in Scythia 627 Nadezhda Avksentyevna Gavrilyuk Volume 2 Distant Chora of Taurian Chersonesus and the City of Kalos Limen 677 Sergey Bo ris -

Ancient Fishing and Fish Processing in the Black Sea Region

BLACK SEA STUDIES 2 The Danish National Research Foundation’s Centre for Black Sea Studies ANCIENT FISHING AND FISH PROCESSING IN THE BLACK SEA REGION Edited by Tønnes Bekker-Nielsen AARHUS UNIVERSITY PRESS ANCIENT FISHING AND FISH PROCESSING IN THE BLACK SEA REGION Proceedings of an interdisciplinary workshop on marine resources and trade in fish products in the Black Sea region in antiquity, University of Southern Denmark, Esbjerg, April 4-5, 2003. Copyright: Aarhus University Press, 2005 Cover design by Jakob Munk Højte and Lotte Bruun Rasmussen Mosaic with scene of fishermen at sea from a tomb in the catacomb of Hermes in Hadrumetum (Sousse Museum, inv.no. 10.455). Late second century AD. 320 x 280 cm. Photo: Gilles Mermet. Printed in Gylling by Narayana Press ISBN 87 7934 096 2 AARHUS UNIVERSITY PRESS Langelandsgade 177 DK-8200 Aarhus N 73 Lime Walk Headington, Oxford OX2 7AD Box 511 Oakville, CT 06779 www.unipress.au.dk The publication of this volume has been made possible by a generous grant from the Danish National Research Foundation Danish National Research Foundation’s Centre for Black Sea Studies Building 328 University of Aarhus DK-8000 Aarhus C www.pontos.dk Contents Illustrations and Tables 7 Introduction 13 Tønnes Bekker-Nielsen Fish as a Source of Food in Antiquity 21 John Wilkins Sources for Production and Trade of Greek and Roman Processed Fish 31 Robert I. Curtis The Archaeological Evidence for Fish Processing in the Western Mediterranean 47 Athena Trakadas The Technology and Productivity of Ancient Sea Fishing 83 Tønnes Bekker-Nielsen The Reliability of Fishing Statistics as a Source for Catches and Fish Stocks in Antiquity 97 Anne Lif Lund Jacobsen Fishery in the Life of the Nomadic Population of the Northern Black Sea Area in the Early Iron Age 105 Nadežda A. -

Les Carnets De L'acost, 13

Les Carnets de l’ACoSt Association for Coroplastic Studies 13 | 2015 Varia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/acost/566 DOI: 10.4000/acost.566 ISSN: 2431-8574 Publisher ACoSt Printed version Date of publication: 5 August 2015 Electronic reference Les Carnets de l’ACoSt, 13 | 2015 [Online], Online since 17 August 2015, connection on 23 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/acost/566 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/acost.566 This text was automatically generated on 23 September 2020. Les Carnets de l'ACoSt est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Editorial Oliver Pilz Coroplastic Studies and the History of Religion: Figurines in Yehud and the Interdisciplinary Nature of the Study of Terracottas Izaak J. de Hulster Ein Affe spielt Tragödie. Zum Problem der Tiermaske bei vermeintlichen und tatsächlichen Schauspielerstatuetten Simone Voegtle Bust Thymiateria from Olbia Pontike Tetiana M. Shevchenko Les terres cuites figurées du sanctuaire de Kirrha (Delphes) : Bilan des premières recherches Stéphanie Huysecom-Haxhi Chroniques Entre la Mésopotamie et l’Indus. Réflexions sur les figurines de terre cuite d’Asie Centrale aux 4e et 3e millénaires Annie Caubet Painted Gallo-Roman Figurines in Vendeuil-Caply Adrien Bossard Travaux en cours A Catalogue of the Greek and Roman Terracottas in the Aydın Archaeological Museum Murat Çekіlmez A Survey of Terracotta Figurines from Domestic Contexts in South Italy in the 6th and 5th Centuries B.C.E. Aura Piccioni Two Collaborative Projects for Coroplastic Research, II. -

K Handmade Pottery

K Handmade pottery Nadežda A. Gavriljuk For a long time it has been believed that those people belonging to the so-called “barbarian world” surrounding ancient Greek towns were the manufacturers and users of handmade pottery. Finds of recent years, however, allow us to propose that this statement is only partly correct. In order to establish a fresh approach to the study of the interrelations between the local and Greek populations of the ancient centres of the northern Black Sea littoral, it is necessary to analyse the archaeological materials from each of these centres. Only interdisciplinary studies of pottery assemblages in their entirety (handmade, wheelmade tableware, cookingware, containers) will enable us to arrive at grounded conclusions as to the use and production of each particular group of pottery, the ratio between the barbarian and Greek components in the material culture of the Greeks of the northern Black Sea region and the history of each Greek polis. The evidence from Olbia, an exemplary site for the study of antiquity in the northern Black Sea littoral, is, in this aspect, of special importance. research history The handmade pottery of Olbia was first considered as a separate find category by T.N. Knipovič.733 Simultaneously, an attempt was made to apply chemical and technological analyses to studies of Olbian pottery,734 and the hypothesis was proposed that a proportion of the handmade pottery belonged to the indigenous population. A differing view about the pottery assemblages of ancient sites was held by V.V. Lapin. Based on the study of handmade pottery from Berezan’ and its comparison with the evidence from other Greek sites including Olynthos, he proposed that the handmade pottery from Berezan’ belonged to the material culture of the Greek population. -

Ifeiii Fev'l Psl Lire Mw :V.R'a*R>T'{»J • Yjj .''Xi.'L"?' KS»I !'Flv''s5iwjr «

ipf ;•»>•.;: i.iS •. i'• - * '. ff!*'.,''!' ''-r •' "i:> \/P~ei_ ho\4er_ 0639- ">j,: \r\> .'. \ *• 1 i'i Li's \ • • >; fr>". •/i ';nf VjiO * 3?j,<?i 'SC^b: '[''-i Ifeiii feV'l PSl lire mW :v.r'A*r>t'{»J • yJj .''Xi.'l"?' KS»i !'fLV''s5iWjR « 5SS'<";iSB»ra'..-,sJi L'J //. 5. huocl'^t^ '4. 5.€4 .1^ Lb ^ .of 12 .XII.61 CATALOGUE 1 \ oV PI* 1 i exj; Miletos. Single "barrel" preserved of top of double-barrelled handle; fragment seen by V.G. in October 1959. A See under A A- PI. 1 (^club 3 ex.: Alexandria. -A^o9\. PI. 1 1 ex.: Athens. Context of first half, perhaps first quarter, of 2nd century B.C. for this handle, SS 9382 from cistern B 20 : 2. club "5. q •SO ex. from four dies: Kos, Athens, 6; A±RXKSJixiJK:(xifi:;^x Delos, ^ fl 2 impressions on a single handle); Alexandria, iO« I Context of early 2nd century B.C. or earlier for SS 554 and 12682 from gSBF; of first half of 2nd century or earlier for SS 6619 from cistern E 6 : 2 PreTious publication: Meroutsos 1874, p.457, no.l (EM 89, from colleeti ou p .£?:2- <liu '.iin\X do't.,aio nmtorole aoln''' stampibito. Do altfJl si B ^ Gr'aK"^ f ci si ?, *'iauii 51 (d i?i (^xpoitii viniinlo nu mim^^ arnioro simple, fara iiici nii sonm ])e olC' 2. STAMPILI-; iNTlUCGri't-; ^1 STAM1MI.I-; j^j-pd-SCIPHAHIL}. 71 o 'ASaiou lAAAlor - Ip'dtp(,'zitnV'^^^^ fara alta "I'Ucatio I fNTOCMAlM.