Les Carnets De L'acost, 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medicinal Vessels from Tell Atrib (Egypt)

Études et Travaux XXX (2017), 315–337 Medicinal Vessels from Tell Atrib (Egypt) A Ł, A P Abstract: This article off ers publication of seventeen miniature vessels discovered in Hellenistic strata of Athribis (modern Tell Atrib) during excavations carried out by Polish- -Egyptian Mission in the 1980s/1990s. The vessels, made of clay, faience and bronze, are mostly imports from various areas within the Mediterranean, including Sicily and Lycia, and more rarely – local imitations of imported forms. Two vessels carry stamps with Greek inscriptions, indicating that they were containers for lykion, a medicine extracted from the plant of the same name, highly esteemed in antiquity. The vessels may be connected with a healing activity practised within the Hellenistic bath complex. Keywords: Tell Atrib, Hellenistic Egypt, pottery, medicinal vessels, lykion, healing activity Adam Łajtar, Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Warszawa; [email protected] Anna Południkiewicz, Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Warszawa; [email protected] Archaeological excavations carried out between 1985 and 1999 by a Polish-Egyptian Mission within the Hellenistic and Roman dwelling districts and industrial quarters of ancient Athribis (modern Tell Atrib), the capital of the tenth Lower Egyptian nome,1 yielded an interesting series of miniature vessels made of clay, faience and bronze.2 Identical or similar vessels are known from numerous sites within the Mediterranean and are considered as containers for medicines in a liquid form. A particularly rich collection of such vessels, amounting to 54 objects, was discovered in the 1950s, during work carried out by an American archaeological expedition in Morgantina 1 For a preliminary presentation of the results, see reports published in journal Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean (vols I–VII, by K. -

A Comparative Study of Ancient Greek City Walls in North-Western Black Sea During the Classical and Hellenistic Times

INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES MA IN BLACK SEA CULTURAL STUDIES A comparative study of ancient Greek city walls in North-Western Black Sea during the Classical and Hellenistic times Thessaloniki, 2011 Supervisor’s name: Professor Akamatis Ioannis Student’s name: Fantsoudi Fotini Id number:2201100018 Abstract Greek presence in the North Western Black Sea Coast is a fact proven by literary texts, epigraphical data and extensive archaeological remains. The latter in particular are the most indicative for the presence of walls in the area and through their craftsmanship and techniques being used one can closely relate these defensive structures to the walls in Asia Minor and the Greek mainland. The area examined in this paper, lies from ancient Apollonia Pontica on the Bulgarian coast and clockwise to Kerch Peninsula.When establishing in these places, Greeks created emporeia which later on turned into powerful city states. However, in the early years of colonization no walls existed as Greeks were starting from zero and the construction of walls needed large funds. This seems to be one of the reasons for the absence of walls of the Archaic period to which lack comprehensive fieldwork must be added. This is also the reason why the Archaic period is not examined, but rather the Classical and Hellenistic until the Roman conquest. The aim of Greeks when situating the Black Sea was to permanently relocate and to become autonomous from their mother cities. In order to be so, colonizers had to create cities similar to their motherlands. More specifically, they had to build public buildings, among which walls in order to prevent themselves from the indigenous tribes lurking to chase away the strangers from their land. -

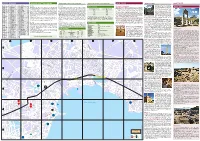

1 2 3 4 5 a B C D E

STREET REGISTER ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND ARRIVING & GETTING AROUND WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE WHAT TO SEE Amurskaya E/F-2 Krasniy Spusk G-3 Radishcheva E-5 By Bus By Plane Great Mitridat Stairs C-4, near the Lenina Admirala Vladimirskogo E/F-3 Khersonskaya E/F-3 Rybatskiy prichal D/C-4-B-5 Churches & Cathedrals pl. The stairs were built in the 1930’s with plans Ancient Cities Admirala Azarova E-4/5 Katernaya E-3 Ryabova F-4 Arriving by bus is the only way to get to Kerch all year round. The bus station There is a local airport in Kerch, which caters to some local Crimean flights Ferry schedule Avdeyeva E-5 Korsunskaya E-3 Repina D-4/5 Church of St. John the Baptist C-4, Dimitrova per. 2, tel. (+380) 6561 from the Italian architect Alexander Digby. To save Karantinnaya E-3 Samoylenko B-3/4 itself is a buzzing place thanks to the incredible number of mini-buses arriving during the summer season, but the only regular flight connection to Kerch is you the bother we have already counted them; Antonenko E-5 From Kerch (from Port Krym) To Kerch (from Port Kavkaz) 222 93. This church is a unique example of Byzantine architecture. It was built in Admirala Fadeyeva A/B-4 Kommunisticheskaya E-3-F-5 Sladkova C-5 and departing. Marshrutkas run from here to all of the popular destinations in through Simferopol State International, which has regular flights to and from Kyiv, there are 432 steps in all meandering from the Dep. -

Kansas City and the Great Western Migration, 1840-1865

SEIZING THE ELEPHANT: KANSAS CITY AND THE GREAT WESTERN MIGRATION, 1840-1865 ___________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________ By DARIN TUCK John H. Wigger JULY 2018 © Copyright by Darin Tuck 2018 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled SEIZING THE ELEPHANT: KANSAS CITY AND THE GREAT WESTERN MIGRATION, 1840-1865 Presented by Darin Tuck, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. __________________________________________________ Professor John Wigger __________________________________________________ Assoc. Professor Catherine Rymph __________________________________________________ Assoc. Professor Robert Smale __________________________________________________ Assoc. Professor Rebecca Meisenbach __________________________________________________ Assoc. Professor Carli Conklin To my mother and father, Ronald and Lynn Tuck My inspiration ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was only possible because of the financial and scholarly support of the National Park Service’s National Trails Intermountain Region office. Frank Norris in particular served as encourager, editor, and sage throughout -

Cv Europeo Italiano

CURRICULUM VITAE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Nome GIOCONDA LAMAGNA Indirizzo Telefono Fax E-mail ***************************** Nazionalità ********** Data di nascita ESPERIENZA LAVORATIVA • Date (da – a) Dal 04/11/2013 ad oggi • Nome e indirizzo del datore di Assessorato Regionale Beni Culturali e Identità Siciliana – Dipartimento Beni lavoro culturali e Identità siciliana, via delle Croci, n. 8 - Palermo • Tipo di impiego Dirigente responsabile del S. 51 Museo Archeologico Regionale Paolo Orsi - Siracusa Conferimento incarico con D.D.G. n. 6190 del 24/10/2013, giusto contratto individuale Rep. n. 2147 del 22/10/2014, successivamente approvato con D.D.G. n. 7138 del 03/11/2014 registrato dalla Ragioneria Centrale BB.CC. e I.S.al n. 1986 del 13.11.2014 • Principali mansioni e Capo d’istituto e funzionario delegato. Nell’ambito di tale incarico ha svolto le responsabilità funzioni istituzionali di coordinamento e gestione delle risorse umane, finanziarie e strumentali assegnatele, con le quali ha condotto le seguenti, principali, attività: Gestione tecnica amministrativa e contabile dell’ufficio, anche attraverso i portali informatici GECORS (adempimenti consegnatario); SI-GTS (attività contabile inerente i vari capp. di spesa); Prosecuzione attività URP; Utilizzo dei sistemi di rilevazione della cd. “customer satisfaction” nella riorganizzazione dei servizi all’utenza Attivazione sistema informatizzato presenze; Pagina 1- Curriculum vitae di [ LAMAGNA Gioconda ] Promozione attività di formazione del personale; Potenziamento e gestione comunicazione tramite social networks Rapporti con le organizzazioni sindacali; Rapporti con gli enti locali; Adempimenti ufficiale rogante; Adempimenti biglietteria ivi compresa attivazione di postazione con terminale POS; Acquisizione di un lotto di una collezione numismatica di importante interesse. Procedure di acquisizione di beni e servizi tramite strumenti CONSIP s.p.a. -

The Public Are Invited

1.4. * ,1'J-. ^.; ^'k liltl iR »>J %> ^: > ^/ V * ^ ^ -' N # I P J- -b£;3iSSi*££3&=S»=: VOL. XXXIII SUMMIT. N, J.. FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 8, I 9 I ts NO. 47 j-rivrt eded Tuesday nigh". 5 Xaniara hud paid the lawyer ijiLi, ;t!-;i PROAOHNCE' BOTE GUILTI ly the intention of thoK? expected Kerrigan and Leslie to r% - the charges to impress on fiUtd half that sum. CouneiIui;;,r the idea that Leslie was? reiownsibU Phraner tangled him some on a sta.t-- OUNCIL EXPELS TWO FIREMAN FOR for the false alarm. KemgailMold o.. nient rhat he had gone right homo a- Leslie leaving the rcoiii as,p of not ter returning from the alarm wldr1. FALSE ALARM CHARGE, returning before the aluriu sounded, failed to jibe with his story that hn and later DuUin and McNnmara with had llrst heard that it was a fills" Charlos Dukin ami Andrew McNamara considerable detail corroborated this alarm from Chief Wilson at the Hot i. story, Kerrigan's cool admission of and-Ladder building that same nigl ;. Are Given Formal Trial and it De perjury amaaed the council, ai. i he City Clerk Kentz before whom Ker was subjected to a gruelling examin velops Some Amazing Testimony — rigan and Leslie made their origin;; 1 ation. He at first declared that he did affidavits, testified to administonuy- One Witness Called Dy the Council not remember any oath when he made the oath, aml—iljOrbert Long told ::•!; the statement embodied in the affi Caimiv Repudiates on Affidavit He Kerrigan's statement to him lhat cc;- davit. -

Atella/Aderl: Confronti Etimologici E Riscontri Geocartografici

GIOVANNI RECCIA ATELLA/ADERL: CONFRONTI ETIMOLOGICI E RISCONTRI GEOCARTOGRAFICI ISTITUTO DI STUDI ATELLANI NOVISSIMAE EDITIONES Collana diretta da Giacinto Libertini --------- 33 --------- GIOVANNI RECCIA ATELLA/ADERL: CONFRONTI ETIMOLOGICI E RISCONTRI GEOCARTOGRAFICI Febbraio 2014 ISTITUTO DI STUDI ATELLANI 1 Istituto di Studi Atellani (ISA) Edizione elettronica a cura di Giacinto Libertini http://www.iststudiatell.org Copyright ISA 2014 Tutti i diritti riservati Prima edizione: Febbraio 2014 2 INTRODUZIONE *L‟etimologia è sempre stata considerata una scienza imperfetta per la possibilità che hanno le lingue di trasformarsi nel corso del tempo, ma se, da un lato, ciò è plausibile quando discerniamo di lingue morte o sconosciute, dall‟altro, tale limite si riduce notevolmente in presenza di forme linguistiche/parole che si riscontrano in maniera multiforme nel corso dei secoli in ragione della possibilità di poterne ricostruire struttura e significato originari. Da tali ricostruzioni però, ad affermare principi ovvero ad evidenziare profili aventi diretti riflessi storici sul territorio o sulla società, credo passi molto, specialmente se non vi sono supporti derivanti dall‟applicazione di scienze ulteriori e diverse. La toponomastica antica quindi, come parte dell‟etimologia, può trovare fondamento soltanto se non viene enunciata in astratto, bensì poggi su elementi e dati riscontrabili sul territorio derivanti dallo studio comparato di altre discipline tra cui la geografia, la storia e l‟archeologia. Venendo dunque al nostro tema e premesso che la città antica di Atella(1), costituita da un *Lo studio riprende quanto accennato in G. RECCIA, Topografonomastica e descrizioni geocartografiche dei comuni atellano-napoletani di Grumo e Nevano, Firenze 2009. (1) Sulla città di Atella e la fabula atellana riporto la seguente bibliografia: D. -

The Chora of Nymphaion (6Th Century BC-6Th Century

The Chora of Nymphaion (6th century BC-6th century AD) Viktor N. Zin’ko The exploration of the rural areas of the European Bosporos has gained in scope over the last decades. Earlier scholars focused on studying particular archaeological sites and an overall reconstruction of the rural territories of the Bosporan poleis as well as on a general understanding of the polis-chora relationship.1 These works did not aim at an in-depth study of the chora of any one particular city-state limited as they were to small-scale excavations of individual settlements. In 1989, the author launched a comprehensive research project on the chora of Nymphaion. A careful examination of archive materials and the results of the surveys revealed an extensive number of previously unknown archaeological sites. The limits of Nymphaion’s rural territory corresponded to natural bor- der-lines (gullies, steep slopes of ridges etc.) impassable to the Barbarian cav- alry. The region has better soils than the rest of the peninsula, namely dark chestnut černozems,2 and the average level of precipitation is 100 mm higher than in other areas.3 The core of the territory was represented by fertile lands, Fig. 1. Map of the Kimmerian Bosporos (hatched – chora of Nymphaion in the 5th century BC; cross‑hatched – chora of Nymphaion in the 4th‑early 3rd centuries BC). 20 Viktor N. Zin’ko stretching from the littoral inland, and bounded to the north and south by two ravines situated 7 km apart. The two ravines originally began at the western extremities of the ancient estuaries (now the Tobečik and Čurubaš Lakes). -

Nwmal"' Tifw" '""Triwrwi Jpjapd"Lrww' I Saturday Press

1 " , ""' " iLnwmaL"' TifW" '""triwrwi jpjapd"lrWW' I Saturday Press. i rOUTiMKIIIfiUiMBBI 34. I., HONOLULU, H. SATURDAY, APRIL 21, 1883. WHOLE NUMBER 138 final SATURDAY PR.2SS, doom j gates detonating ami shreiMng at tTuriiij. they burst from prton-hmrt- IJrofcooiomtl cOuoincflO cOuoincoo (Turbo. Ihcfr hot 1 the cpuoincoa Curb or. Snounmcc oticco. a atmosphere (General bbciitocmcuto. A Newspaper Published Wttlly. dark, turgid ami opprewhe; while cave an.I hollow, at the hot air swept alone XflLLlAM O. SMITH, 1UT S, ORINDAUM & their heatcsl wallt, threw back the unearthly Co. T H. LYNCH, QOSMOPOLITAN RESTAURANT, TRANS-ATLANTI- PIRB INSURANCE IONEER" $5.00 1 ,111, i und, In a mtriad of prolonged .1 Company of LINE uut srmirnim wive. echoes. Such rroitxKV .ir Mir, Makuk's Mlock, Qi mi Srsssr, J as Klnir street, .V. C.IM.ICIIO, I'refHtler, Hamburg, wai the scene as the fiery "p Foreign rebecnptKms cataract, leaping a 01 .UiKitsNT Sriiir, ItnNoii'U, jo rjti'oiiri:it.sAxi nnowiAr.i: Drttlrr In r.rrru of lloolt . ItACKFKLD & C., Aftnli. precipice of fifty feel, poured its flood upon the ukau, Itfrrlfllnn No. 6s llorri Street, Honolulu, II. I, SeV.cn rr lit Of r. unit .fiof. to $7 50, acctrlit to tbett destination. 1 inIf Capital and Reserve Relthsmatk from Liverpool ocean. he old line or coast, a maw of com- ,nm,oon R. CASTLE, Ladles and Gents' Fine Wear a Specialty. their Companies " iat,oso,csn pact, Indurated lava, whitened, cracked and yir S. GRINDAUM & Co. IV Jtealt at all hour; Ihe i.;.N-i- f fell. -

Sicily UMAYYAD ROUTE

SICILY UMAYYAD ROUTE Umayyad Route SICILY UMAYYAD ROUTE SICILY UMAYYAD ROUTE Umayyad Route Index Sicily. Umayyad Route 1st Edition, 2016 Edition Introduction Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí Texts Maria Concetta Cimo’. Circuito Castelli e Borghi Medioevali in collaboration with local authorities. Graphic Design, layout and maps Umayyad Project (ENPI) 5 José Manuel Vargas Diosayuda. Diseño Editorial Free distribution Sicily 7 Legal Deposit Number: Gr-1518-2016 Umayyad Route 18 ISBN: 978-84-96395-87-9 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, nor transmitted or recorded by any information retrieval system in any form or by any means, either mechanical, photochemical, electronic, photocopying or otherwise without written permission of the editors. Itinerary 24 © of the edition: Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí © of texts: their authors © of pictures: their authors Palermo 26 The Umayyad Route is a project funded by the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI) and led by the Cefalù 48 Andalusian Public Foundation El legado andalusí. It gathers a network of partners in seven countries in the Mediterranean region: Spain, Portugal, Italy, Tunisia, Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan. Calatafimi 66 This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union under the ENPI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the beneficiary (Fundación Pública Castellammare del Golfo 84 Andaluza El legado andalusí) and their Sicilian partner (Associazione Circuito Castelli e Borghi Medioevali) and can under no Erice 100 circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union or of the Programme’s management structures. -

Annual Report 2005

NATIONAL GALLERY BOARD OF TRUSTEES (as of 30 September 2005) Victoria P. Sant John C. Fontaine Chairman Chair Earl A. Powell III Frederick W. Beinecke Robert F. Erburu Heidi L. Berry John C. Fontaine W. Russell G. Byers, Jr. Sharon P. Rockefeller Melvin S. Cohen John Wilmerding Edwin L. Cox Robert W. Duemling James T. Dyke Victoria P. Sant Barney A. Ebsworth Chairman Mark D. Ein John W. Snow Gregory W. Fazakerley Secretary of the Treasury Doris Fisher Robert F. Erburu Victoria P. Sant Robert F. Erburu Aaron I. Fleischman Chairman President John C. Fontaine Juliet C. Folger Sharon P. Rockefeller John Freidenrich John Wilmerding Marina K. French Morton Funger Lenore Greenberg Robert F. Erburu Rose Ellen Meyerhoff Greene Chairman Richard C. Hedreen John W. Snow Eric H. Holder, Jr. Secretary of the Treasury Victoria P. Sant Robert J. Hurst Alberto Ibarguen John C. Fontaine Betsy K. Karel Sharon P. Rockefeller Linda H. Kaufman John Wilmerding James V. Kimsey Mark J. Kington Robert L. Kirk Ruth Carter Stevenson Leonard A. Lauder Alexander M. Laughlin Alexander M. Laughlin Robert H. Smith LaSalle D. Leffall Julian Ganz, Jr. Joyce Menschel David O. Maxwell Harvey S. Shipley Miller Diane A. Nixon John Wilmerding John G. Roberts, Jr. John G. Pappajohn Chief Justice of the Victoria P. Sant United States President Sally Engelhard Pingree Earl A. Powell III Diana Prince Director Mitchell P. Rales Alan Shestack Catherine B. Reynolds Deputy Director David M. Rubenstein Elizabeth Cropper RogerW. Sant Dean, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts B. Francis Saul II Darrell R. Willson Thomas A. -

Dating the Monuments of Syracusan Imperialism

Syracuse in antiquity APPENDIX 4: DATING THE MONUMENTS OF SYRACUSAN IMPERIALISM Archaic Period Apollonion and Artemision on Ortygia Zeus Urios at Polichne Gelon Work starts on the temple of Athena (485-480) Temples to Demeter and Kore, and Demeter at Aetna (Katane) Tombs of the Deinomenids on the road to Polichne Ornamental Pool at Akragas, statuary at Hipponion Hieron I Theatre at Neapolis (after) 466 An altar to Zeus Eleutherios 450-415 Temenos of Apollo at Neapolis 415 Fortification of Neapolis and Temenites Garden at Syracuse Dionysius I Fortification of the Mole and Small Harbour Construction of acropoleis on Ortygia and the Mole Embellishment of the agora Completion of the northern wall on Epipolai, the Hexapylon and Pentapylon Foundation of Tyndaris Destruction of the tombs of Gelon and Demarete Completion of the circuit walls of the city Dionysius II Re-foundation of Rhegion as Phoebia Two colonies founded in Apulia Destruction of the acropoleis and fortifications of the Mole and Ortygia Timoleon Construction of the Timoleonteion Re-foundation of Gela, Akragas and Megara Hyblaia Gymnasium and Tomb of Timoleon near the agora Agathokles Fortifications of Gela A harbour at Hipponion The Eurialos Fort 150 Appendix A Banqueting Hall on Ortygia Refortification of Ortygia and the Partus Laccius Decoration of the interior of the Athenaion Re-foundation of Segesta as Dikaiopolis Hieron II Palace on Ortygia The Theatre at Neapolis Altar of Zeus Eleutherios renovated Olympieion in the agora Hieronymous Refinement of fortifications at Eurialos 151 Syracuse in antiquity APPENDIX 5: THE PROCONSULS OF SICILY (210-36 BC)1 211: M.