Bruce Crandall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salute for the Ages D.C

GRADUATION DAY, 10 a.m., Saturday at Michie Stadium. Congratulations to the Class of 2010. OINTER IEW ® PVOL . 67, NO. 19 SERVING THE COMMUNITY OF WVE S T POINT , THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY MAY 20, 2010 New Supe nominated Huntoon chosen to be next academy leader WASHINGTON––Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates announced Tuesday that President Barack Obama has nominated Lt. Gen. David H. Huntoon, Jr. for reappointment to the rank of lieutenant general and assignment as the 58th Superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. A 1973 West Point graduate, Huntoon was commissioned in the infantry and, after attending Infantry Officer Basic, served with the 3rd Infantry Regiment (The Old Guard) at Fort Myer, Va. He later became commander of the regiment. He served with the 9th Division at Fort Lewis, Wash., the 3rd Infantry Division (Mechanized) in Germany and attended Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., and later became Deputy Commandant there. During Operations Just Cause and Desert Storm, he served with the XVIII Airborne Corps in Fort Bragg, N.C. He was the Commandant of the United States Army War College at Carlisle Barracks, Pa., and is currently serving as Director of the Army Staff, United States Army, Washington, Salute for the Ages D.C. Huntoon earned a master’s degree in Retired Gen. Ralph E. Haines, Jr., 96, accompanied by Cadet First Captain Tyler Gordy salute the “Father of the international relations from Georgetown Academy” Sylvanus Thayer at the foot of Thayer Statue during the annual alumni wreath-laying ceremony Tuesday University. -

Vietnam: Tet Offensive Resource Packet

Virginians at War Vietnam: Tet Offensive Resource Packet Contains: Glossary, Timeline, Images, Discussion Questions, Additional Resources Program Description: Virginians at War: The Tet Offensive explores the experience of Virginians that fought during the critical Tet Offensive in 1968, a turning point of the Vietnam War. Launched by the North Vietnamese Army on 30 January, the coordinated attack against thirteen different provincial capitals throughout South Vietnam took Americans and South Vietnamese by surprise. The result was a costly, long campaign that ended in a hard –fought military victory for the United States and South Vietnamese. However, the outcome of the campaign had a significantly negative impact on support for the war in the United States, from which the nation would not fully recover. Copyright: Virginia War Memorial Foundation, 2006 Length: 18:59 Streaming link: https://vimeo.com/367038067 Featured Speakers: MSG Lonnie S. Ashton, Montross SPC Orthea Harcum, Richmond MSG Lauren P. Bands, Colonial Heights LT Hugh D. Keogh, Midlothian COL Robert C. Barrett, Jr., Colonial Heights SGT Prentis Lee, Clifton LT COL Frank S. Blair, Richmond SP/4 Powhatan “Red Cloud” Owen, Charles City MSG Charles M. Carter, Warsaw SGM Douglass I. Randolph, Charlotte Court House SGT Earl E. Cousins, Ashland MAJ John A. Rawls, M.D., Mechanicsville CPT James H. Dement, Jr., Richmond 1st LT Cathie Lynn Solomonson, R.N., Woodbridge 1st LT Daniel G. Doyle, Richmond 1st LT James F. Walker, Roanoke LT COL John D. Edgerton, Williamsburg For a transcript of this program and more information on the Vietnam War, please visit vawarmemorial.org/learn/resources/vietnam. -

Through the Hollywood Lens: the Vietnam War 3

Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at W&M Summer 2020 Through the Hollywood Lens: The Vietnam War Scott A. Langhorst, Ph.D. First Lieutenant 4th Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment 25th Division Tay Ninh, Vietnam (1969-70) Using Zoom tools - reminder • Use the menu bar (mouse over bottom/top of screen) to appear • Use icons to on menu bar open tools (click “on” click “off”) • Use “chat box” to ask questions or make comments • Use “participant” list for raising hand or other gestures • Make the session interactive by using the Zoom tools © Scott A. Langhorst, Ph.D. 1 Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at W&M Summer 2020 Questions or comments from last week? 1Lt Langhorst at FSB Rhode Island Forrest Gump (1994) • Directed by Robert Zemeckis • Won 6 Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Actor • Nominated for 7 other Oscars • Vietnam sequences filmed on Fripp Island, SC • Storyline: After many 1960’s adventures, Forrest joins the Army and goes to Vietnam. He makes a new friend, Bubba, who dies in his arms after an violent ambush. Forrest is able to save the rest of his squad and a reluctant Lt. Dan. Forrest comes home to an America that is divided, and saves a paraplegic Lt. Dan once again. He is a witness to the aftermath of Vietnam and the healing of America. © Scott A. Langhorst, Ph.D. 2 Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at W&M Summer 2020 What the movie got right • (Why “Forrest Gump” in a course about the Vietnam War?) • One film segment is about Forrest as a soldier in Vietnam (2/47 Inf. -

WFLDP Leadership in Cinema – We Were Soldiers 2 of 10 Facilitator Reference

Facilitator Reference WE WERE SOLDIERS Submitted by: Pam McDonald .......................................................... E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 208-387-5318 Studio: Paramount .............................................................................................. Released: 2002 Genre: Drama ................................................................................................ Audience Rating: R Runtime: 138 minutes Materials VCR or DVD, television or projection system, Wildland Fire Leadership Values and Principles handouts (single-sided), Incident Response Pocket Guide (IRPG), notepad, writing utensil Objective Students will identify Wildland Fire Leadership Values and Principles illustrated within We Were Soldiers and discuss leadership lessons learned with group members or mentors. Basic Plot In 1965, 400 American troops faced an ambush by 2,000 enemy troops in the Ia Drang Valley (also known as the Valley of Death), in one of the most gruesome fights of the Vietnam War. We Were Soldiers is a detailed recreation of this true story: of the strategies, obstacles, and human cost faced by the troops that participated. The story focuses on the lieutenant colonel that led the attack, Hal Moore (Mel Gibson), and a civilian reporter who accompanied them, Joseph Galloway (Barry Pepper), as well as a number of other soldiers who were involved. (Taken from Rotten Tomatoes) We Were Soldiers is the story of a group that trained and sweated with one another—connected together in a way that only those who have shared similar settings can be—that entered into a chaotic situation, relied on one another for support and survival, and who eventually emerged— bruised and battered, but successful nonetheless. Set in war, the lesson is not about war, but about followership, leadership, and shared values. (From Paul Summerfelt, FFD-FMO, Flagstaff, AZ). -

P R O C E E D I N G S of the of the United States

107th_covers 6/21/07 10:41 AM Page 1 110th Congress, 1st Session ......................................................House Document 110-40 P R O C E E D I N G S OF THE 107th NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES [SUMMARY OF MINUTES] Reno, Nevada : : : August 26 - August 31, 2006 107TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS 107th_backstrip 6/21/07 10:58 AM Page 1 107th_covers 6/21/07 10:41 AM Page I 110th Congress, 1st Session ......................................................House Document 110-40 PROCEEDINGS of the 107th ANNUAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Reno, Nevada August 26-31, 2006 Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed. U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2007 36-122 107th 5/25/07 1:05 PM Page II U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the Amer- ican Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House doc- uments of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] II 107th 6/22/07 3:11 PM Page III LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, RENO, NEVADA, April, 2007 Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Speaker U.S. -

JFQ 31 JFQ▼ FORUM Sponds to Aggravated Peacekeeping in Joint Pub 3–0

0203 C2 & Pgs 1-3 3/3/04 9:07 AM Page ii The greatest lesson of this war has been the extent to which air, land, and sea operations can and must be coordinated by joint planning and unified command. —General Henry H. (“Hap”) Arnold Report to the Secretary of War Cover 2 0203 C2 & Pgs 1-3 3/27/04 7:18 AM Page iii JFQ Page 1—no folio 0203 C2 & Pgs 1-3 3/3/04 9:07 AM Page 2 CONTENTS A Word from the Chairman 4 by John M. Shalikashvili In This Issue 6 by the Editor-in-Chief Living Jointness 7 by William A. Owens Taking Stock of the New Joint Age 15 by Ike Skelton JFQ Assessing the Bottom-Up Review 22 by Andrew F. Krepinevich, Jr. JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY Living Jointness JFQ FORUM Bottom-Up Review Standing Up JFQ Joint Education Coalitions Theater Missle Vietnam Defense as Military History Standing Up Coalitions Atkinson‘s Crusade Defense Transportation 25 The Whats and Whys of Coalitions 26 by Anne M. Dixon 94 W93inter Implications for U.N. Peacekeeping A PROFESSIONAL MILITARY JOURNAL 29 by John O.B. Sewall PHOTO CREDITS The cover features an Abrams main battle tank at National Training Center (Military The Cutting Edge of Unified Actions Photography/Greg Stewart). Insets: [top left] 34 by Thomas C. Linn Operation Desert Storm coalition officers reviewing forces in Kuwait City (DOD), [bottom left] infantrymen fording a stream in Vietnam Preparing Future Coalition Commanders (DOD), [top right] students at the Armed Forces Staff College (DOD), and [bottom right] a test 40 by Terry J. -

Snazzlefrag's History of the Vietnam War DSST Study Notes

Snazzlefrag’s History of the Vietnam War DSST Study Notes Contact: http://www.degreeforum.net/members/snazzlefrag.html Hosted at: http://www.free-clep-prep.com Han/Tang Dynasty ruled Vietnam for 1000 years. Buddhism 939 Independence from China (1279 Repelled/1407 Invaded(Ming)/1428 Free) 1620 Vietnam divided b/n Trinh (North-Hanoi) Nguyen (South-Hue[fertile Mekong]). 1858 French invade. 1862 (treaty) Protectorate of CochinChina (Capital: Saigon, SV). 1887 Vietnam (Tonkin/Annam)/Cambodia=French Indochina. Catholicism. 1893 Laos added into Indochina. 1919 France ignores Ho Chi Minh’s demands at Versailles Peace Conference. Rep in Fr Parliament. Free speech. Political Prisoners. 1926 Bao Dai becomes last Vietnamese Emperor (supported by French). 1927 Vietnamese Nationalist Party (VNQDD). Vietnam Quoc Dan Dang. "Nguyen Thai Hoc" 1930 Ho founds Indochinese Communist Party (PCI) 1940 Japan occupies Vietnam (keeps Fr. bureaucracy in place to run Fr. Indochina). 1941 Ho Chi Minh founds Viet Minh League for Viet Indep. (Comm/soc/nats). 1941 King Sihanouk of Cambodia given throne by French. Overthrown in 1970 coup. 1945 Japs take complete control but Viet Minh takes Hanoi in August Revolution (not a rev). China moves into NV (as planned by allies). Set up adminstration down to 16th Parallel. Sept 2, Emperor Bao Dai abdicates in favour of Ho Chi Minh. Japan surrenders WWII Ho takes power (president), establishes Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) Truman rejects DRV’s request for formal recognition. 1945 Sept 26: OSS Lt Col Peter Dewey (repating US POWs) shot. 1st US Casualty in Vietnam. 1945 Oct: British/Indian troops move in to SV. -

Heirpower! Eight Basic Habits of Exceptionally Powerful Lieutenants

Heirpower! Eight Basic Habits of Exceptionally Powerful Lieutenants BOB VÁSQUEZ Chief Master Sergeant, USAF, Retired Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama June 2006 front.indd 1 7/17/06 3:22:50 PM Air University Library Cataloging Data Vásquez, Bob. Heirpower! : eight basic habits of exceptionally powerful lieutenants / Bob Vásquez. p. ; cm. ISBN 1-58566-154-6 1. Command of troops. 2. Leadership. I. Title. 355.33041––dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii front.indd 2 7/17/06 3:22:51 PM Contents Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . v ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii PREFACE . ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . xi INTRODUCTION . xiii Habit 1 Get a Haircut! First Impressions Last . 1 Habit 2 Shut Up! Listen and Pay Attention . 9 Habit 3 Look Up! Attitude Is Everything . 15 Habit 4 Be Care-Full! Take Care of Your Troops . 23 Habit 5 Sharpen the Sword! Take Care of Yourself First. 35 Habit 6 Be Good! Know Your Stuff . 45 Habit 7 Build Trust! Be Trustworthy . 51 Habit 8 Hang on Tight! Find an Enlisted Mentor . 59 FINAL THOUGHTS . 67 iii front.indd 3 7/17/06 3:22:51 PM THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Foreword Chief Bob Vásquez has found an innovative and effective way to share some basic principles that every new lieutenant should know on the subject of how to succeed as a leader in our great Air Force. -

Video Log Joseph D. Tramontano Vietnam War U.S. Army Born: 10/13/1944

Video Log Joseph D. Tramontano Vietnam War U.S. Army Born: 10/13/1944 Interview Date: 07/07/2012 Interviewed By: Eileen Hurst 00:00:00 Introduction 00:00:34 Tramontano was a paratrooper in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War. 00:00:43 He achieved the rank of sergeant. 00:00:48 He served in Pleiku, Plei Me, An Khe, Kontum, Bong-Sohn, Ia Drang, Chu Pong, LZ Betty, LZ Mary, LZ English, Cambodia, Laos, North Vietnam, and Thailand. He was a scout for the Army. 00:01:35 He enlisted on March 13, 1963. 00:01:47 He was living in Ansonia, CT at the time. 00:02:02 After graduating from high school, he felt he wasn’t “college material.” Instead, he joined his preferred military branch. 00:02:29 He chose the Army because he wanted to be a paratrooper (like his uncle). 00:02:44 His uncle was a paratrooper in World War II, who completed two combat jumps during the war. 00:02:59 He completed his basic training at Fort Dix, NJ. The course lasted for eight weeks, then an additional eight weeks of advanced infantry training. He then completed both airborne and air assault training at Fort Benning, GA. 00:03:41 He felt scared and disoriented during the first eight weeks of basic training. It was difficult to endure without having his family nearby. 00:04:25 He was considered a light infantryman or a “111.” As a consequence, he was trained to use a rifle, machine gun, pistol, grenade launcher, flamethrower, and grenades. -

Teacher's Guide Produced and Distributed By: Www

Teacher’s Guide Produced and Distributed by: www.MediaRichLearning.com AMERICA IN THE 20TH CENTURY: VIETNAM TEACHER’S GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Materials in Unit .................................................... 3 Introduction to the Series .................................................... 3 Introduction to the Program .................................................... 3 Standards .................................................... 5 Instructional Notes .................................................... 6 Suggested Instructional Procedures .................................................... 7 Student Objectives .................................................... 7 Follow-Up Activities .................................................... 7 Internet Resources .................................................... 10 Answer Key .................................................... 10 Script of Video Narration .................................................... 13 Blackline Masters Index .................................................... 39 Pre-Test .................................................... 40 Quiz .................................................... 41 Post-Test .................................................... 42 Vocabulary Terms .................................................... 49 Legacy of Ashes .................................................... 32 Heros and Heroines .................................................... 33 Songs of Protest .................................................... 34 The Great Debate -

The Columbia Guide to the Vietnam War

Anderson_00FM 5/3/02 9:25 AM Page i The Columbia Guide to the Vietnam War COLUMBIA GUIDES TO AMERICAN HISTORY AND CULTURES Anderson_00FM 5/3/02 9:25 AM Page ii Columbia Guides to American History and Cultures Michael Kort, The Columbia Guide to the Cold War Catherine Clinton and Christine Lunardini, The Columbia Guide to American Women in the Nineteenth Century David Farber and Beth Bailey, editors, The Columbia Guide to America in the 1960s Anderson_00FM 5/3/02 9:25 AM Page iii The Columbia Guide to the Vietnam War David L. Anderson columbia university press new york Anderson_00FM 5/3/02 9:25 AM Page iv Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © 2002 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Anderson, David L., 1946– The Columbia guide to the Vietnam War / David L. Anderson. p. cm. — (Columbia guides to American history and cultures) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–231–11492–3 1. Vietnamese Conflict, 1961–1975. I. Title. II. Series. DS557.5 .A54 2002 959.704Ј3—dc21 2002020143 ∞ Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Anderson_00FM 5/3/02 9:25 AM Page v contents Introduction xi List of Abbreviations xiii part i Historical Narrative 1 1. Studying the Vietnam War 3 2. Vietnam: Historical Background 7 Roots of the Vietnamese Culture and State 7 The Impact of French Colonialism 10 The Rise of Vietnamese Nationalism 11 The Origins of Vietnamese Communism 12 3. -

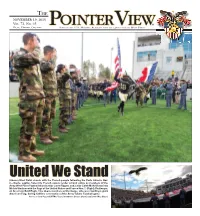

DPE Presents Lt. Gen. Hal Moore Award to First Class Cadets by Michelle Eberhart What Would That Be?” the West Point Assistant Editor Lt

NOVEMBER 19, 2015 1 THE NOVEMBER 19, 2015 VOL. 72, NO. 45 ® UTY ONOR OUNTRY OINTER IEW D , H , C PSERVING THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY AND THE COMMUNITY V OF WEST POINT ® United We Stand (Above) West Point stands with the French people following the Paris Attacks Nov. 6—liberté, égalité, fraternity. French cadets render a hand salute as members of the Army West Point Football team (senior Jared Rogers and junior Caleb McNeill) run into Michie Stadium with the fl ags of the United States and France Nov. 7. (Right) Challenger, an American Bald Eagle, fl ies above members of the Corps, who were holding a giant American Flag, during halftime ceremonies of the Army-Tulane Football game. PHOTOS BY JOHN PELLINO/DPTMS, VISUAL INFORMATION DIVISION (ABOVE) AND DANNY WILD (RIGHT) 2 NOVEMBER 19, 2015 NEWS & FEATURES POINTER VIEW MacShort Barracks RACISM & RESPECT renovation now complete Dear West Point community, By Matthew Talaber In light of recent events at the University of Missouri, Yale University Public Works Director and other colleges around the country, I’d like to talk for a moment about respect, our values and who we are as leaders in our profession. On Nov. 11, the Directorate of Public Works completed the At the heart of these events which have made national headlines are renovation of MacArthur Short Barracks. MacShort is the second racially insensitive and derogatory remarks and actions toward a particular of nine existing barracks to be renovated as part of Army’s Cadet group of students and institution’s perceived failure to properly address Barracks Upgrade Program.