Television Coverage of the Vietnam War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shadows and Wind

1 HUMAN RIGHTS UNDER VIETNAMESE COMMUNISM A Politically Incorrect Approach Ottawa, February 2001 For Human Rights (Huntington Beach, C.A.) March 2001 Ton That Thien American anti-war writers and Vietnam For decades, the literature on Vietnam was strongly dominated by a coterie of Western - predominantly American – journalists and academics who claimed to be experts on Vietnam. These “experts” were fiercely anti-war revolutionaries determined to bring down South Vietnam for internal American reasons. South Vietnam provided the most convenient focus for the anti-war denunciations and demonstrations. As David Horowitz, one of the most radical leaders of the American anti-war movement wrote in his reflections after the war: “My speech illustrated the real importance of Vietnam to the radical cause, which was not ultimately about Vietnam but about our antagonism to America in our desire for revolution. Vietnam served to justify the desire; we needed the war and its violent images to vindicate our destructive intentions”.1 Typical of the above attitude is the “Indo-China Peace Campaign” organized by the famed actress Jane Fonda, which “worked tirelessly to ensure the victory of the North Vietnamese Communists...Fonda travelled first to Hanoi and then to the liberated zones of South Vietnam to make a propaganda film... it attempted to persuade viewers that the Communists were going to create a new society in the south. Equality and justice awaited its inhabitants if only America would cut off support for the Saigon regime...”2 Another illustration is that of Frances Fitzgerald, author of the best seller and Pulitzer Prize winning book, Fire in the Lake. -

Intelligence Memorandum

Approved for Release: 2018/07/26 C02962544 ,E .._, ....,, TolLSect:ef: -1L_____ -------' 3.5(c) DIRECTORATE OF INTELLIGENCE Intelligence Memorandum CAMBODIAANDTHE VIETNAMESE COMMUNISTS ... 3.5(c) 3.5(c) 29 January 1968 I Approved for Release: 2018/07/26 C02962544 3.5(c) Approved for Release: 2018/07/26 C02962544 Approved for Release: 2018/07/26 C02962544 3.5(c) CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Directorate of Intelligence 29 January 1968 INTELLIGENCE MEMORANDUM Cambodia and the Vietnamese Communists A Monthly Report Contents I. Military Developments: Communist battal~ ion and regimental size units continue to operate in Cambodian territory (Paras. 1-5). It is clear that North Vietnamese forces have had bases in the Cam bodian salient since mid-1965 (Paras. 6-8). The salient, however, has never been one of the major Communist base areias .in Cambodia (Paras. 9-12). A 3.3(h)(2) Cambodian~-----~ reports Communist units in South Vietnam are receiving Chinese arms and ammuni tion from Cambodian stocks (Paras. 13--16) . More reports have been received on Cambodian rice sales to the Corru:nunists (Paras. 17-20). Cambodian smug glers are supplying explosive chemicals to the Viet Cong (Para. 21). II. Poli ti cal Developments: Sihanouk"' con cerned over possible allied action against Communists in Cambodia for sanctuary, has reverted to diplomacy to settle the cris:is (Paras. 22-27). Sihanouk has again attempted to get a satisfactory border declara tion from the US (Para. 28). Cambodia, still believ ing the Communists will prevail in South Vietnam, sees short-term advantages to an opening to the West (Para. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

The Legacy of American Photojournalism in Ken Burns's

Interfaces Image Texte Language 41 | 2019 Images / Memories The Legacy of American Photojournalism in Ken Burns’s Vietnam War Documentary Series Camille Rouquet Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/647 DOI: 10.4000/interfaces.647 ISSN: 2647-6754 Publisher: Université de Bourgogne, Université de Paris, College of the Holy Cross Printed version Date of publication: 21 June 2019 Number of pages: 65-83 ISSN: 1164-6225 Electronic reference Camille Rouquet, “The Legacy of American Photojournalism in Ken Burns’s Vietnam War Documentary Series”, Interfaces [Online], 41 | 2019, Online since 21 June 2019, connection on 07 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/interfaces/647 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/interfaces.647 Les contenus de la revue Interfaces sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. THE LEGACY OF AMERICAN PHOTOJOURNALISM IN KEN BURNS’S VIETNAM WAR DOCUMENTARY SERIES Camille Rouquet LARCA/Paris Sciences et Lettres In his review of The Vietnam War, the 18-hour-long documentary series directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick released in September 2017, New York Times television critic James Poniewozik wrote: “The Vietnam War” is not Mr. Burns’s most innovative film. Since the war was waged in the TV era, the filmmakers rely less exclusively on the trademark “Ken Burns effect” pans over still images. Since Vietnam was the “living-room war,” played out on the nightly news, this documentary doesn’t show us the fighting with new eyes, the way “The War” did with its unearthed archival World War II footage. -

The Vietnam War

Fact Sheet 1: Introduction- the Vietnam War Between June 1964 and December 1972 around 3500 New Zealand service personnel served in South Vietnam. Unlike the First and Second World Wars New Zealand’s contribution in terms of personnel was not huge. At its peak in 1968 the New Zealand force only numbered 543. Thirty-seven died while on active service and 187 were wounded. The Vietnam War – sometimes referred to as the Second Indochina War – lasted from 1959 to 1975. In Vietnam it is referred to as the American War. It was fought between the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) and its allies, and the US-supported Republic of Vietnam in the south. It ended with the defeat of South Vietnam in April 1975. Nearly 1.5 million military personnel were killed in the war, and it is estimated that up to 2 million civilians also died. This was the first war in which New Zealand did not fight with its traditional ally, Great Britain. Our participation reflected this country’s increasingly strong defence ties with the United States and Australia. New Zealand’s involvement in Vietnam was highly controversial and attracted protest and condemnation at home and abroad. A study of New Zealand’s involvement in the Vietnam War raises a number of issues. As a historical study we want to find out what happened, why it happened and how it affected people’s lives. This war meant different things to different people. The Vietnam War was, and still is, an important part of the lives of many New Zealanders. -

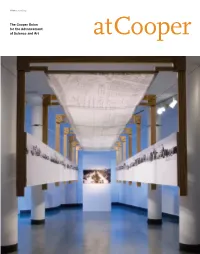

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art Atcooper 2 | the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art

Winter 2008/09 The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art atCooper 2 | The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art Message from President George Campbell Jr. Union The Cooper Union has a history characterized by extraordinary At Cooper Union resilience. For almost 150 years, without ever charging tuition to a Winter 2008/09 single student, the college has successfully weathered the vagaries of political, economic and social upheaval. Once again, the institution Message from the President 2 is facing a major challenge. The severe downturn afflicting the glob- al economy has had a significant impact on every sector of American News Briefs 3 U.S. News & World Report Ranking economic activity, and higher education is no exception. All across Daniel and Joanna Rose Fund Gift the country, colleges and universities are grappling with the prospect Alumni Roof Terrace of diminished resources from two major sources of funds: endow- Urban Visionaries Benefit ment and contributions. Fortunately, The Cooper Union entered the In Memory of Louis Dorfsman (A’39) current economic slump in its best financial state in recent memory. Sue Ferguson Gussow (A’56): As a result of progress on our Master Plan in recent years, Cooper Architects Draw–Freeing the Hand Union ended fiscal year 2008 in June with the first balanced operat- ing budget in two decades and with a considerably strengthened Features 8 endowment. Due to the excellent work of the Investment Committee Azin Valy (AR’90) & Suzan Wines (AR’90): Simple Gestures of our Board of Trustees, our portfolio continues to outperform the Ryan (A’04) and Trevor Oakes (A’04): major indices, although that is of little solace in view of diminishing The Confluence of Art and Science returns. -

Vietnam: Tet Offensive Resource Packet

Virginians at War Vietnam: Tet Offensive Resource Packet Contains: Glossary, Timeline, Images, Discussion Questions, Additional Resources Program Description: Virginians at War: The Tet Offensive explores the experience of Virginians that fought during the critical Tet Offensive in 1968, a turning point of the Vietnam War. Launched by the North Vietnamese Army on 30 January, the coordinated attack against thirteen different provincial capitals throughout South Vietnam took Americans and South Vietnamese by surprise. The result was a costly, long campaign that ended in a hard –fought military victory for the United States and South Vietnamese. However, the outcome of the campaign had a significantly negative impact on support for the war in the United States, from which the nation would not fully recover. Copyright: Virginia War Memorial Foundation, 2006 Length: 18:59 Streaming link: https://vimeo.com/367038067 Featured Speakers: MSG Lonnie S. Ashton, Montross SPC Orthea Harcum, Richmond MSG Lauren P. Bands, Colonial Heights LT Hugh D. Keogh, Midlothian COL Robert C. Barrett, Jr., Colonial Heights SGT Prentis Lee, Clifton LT COL Frank S. Blair, Richmond SP/4 Powhatan “Red Cloud” Owen, Charles City MSG Charles M. Carter, Warsaw SGM Douglass I. Randolph, Charlotte Court House SGT Earl E. Cousins, Ashland MAJ John A. Rawls, M.D., Mechanicsville CPT James H. Dement, Jr., Richmond 1st LT Cathie Lynn Solomonson, R.N., Woodbridge 1st LT Daniel G. Doyle, Richmond 1st LT James F. Walker, Roanoke LT COL John D. Edgerton, Williamsburg For a transcript of this program and more information on the Vietnam War, please visit vawarmemorial.org/learn/resources/vietnam. -

Air America in South Vietnam I – from the Days of CAT to 1969

Air America in South Vietnam I From the days of CAT to 1969 by Dr. Joe F. Leeker First published on 11 August 2008, last updated on 24 August 2015 I) At the times of CAT Since early 1951, a CAT C-47, mostly flown by James B. McGovern, was permanently based at Saigon1 to transport supplies within Vietnam for the US Special Technical and Economic Mission, and during the early fifties, American military and economic assistance to Indochina even increased. “In the fall of 1951, CAT did obtain a contract to fly in support of the Economic Aid Mission in FIC [= French Indochina]. McGovern was assigned to this duty from September 1951 to April 1953. He flew a C-47 (B-813 in the beginning) throughout FIC: Saigon, Hanoi, Phnom Penh, Vientiane, Nhatrang, Haiphong, etc., averaging about 75 hours a month. This was almost entirely overt flying.”2 CAT’s next operations in Vietnam were Squaw I and Squaw II, the missions flown out of Hanoi in support of the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu in 1953/4, using USAF C-119s painted in the colors of the French Air Force; but they are described in the file “Working in Remote Countries: CAT in New Zealand, Thailand-Burma, French Indochina, Guatemala, and Indonesia”. Between mid-May and mid-August 54, the CAT C-119s continued dropping supplies to isolated French outposts and landed loads throughout Vietnam. When the Communists incited riots throughout the country, CAT flew ammunition and other supplies from Hanoi to Saigon, and brought in tear gas from Okinawa in August.3 Between 12 and 14 June 54, CAT captain -

Hitler from American Ex-Pats' Perspective

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • MARCH 2012 Hitler From American Ex-Pats’ Perspective EVENT PREVIEW: MARCH 19 by Sonya K. Fry There have been many history books written about World War II, the economic reasons for Hitler’s rise to power, the psychology of Adolf Hitler as an art student, and a myriad of topics delving into the phenome- non that was Hitler. Andy Nagorski’s new book Hitlerland looks at this time frame from the perspective of American expatriates who lived in Andrey Rudakov Germany and witnessed the Nazi rise Andrew Nagorski to power. In researching Hitlerland, Na- Even those who did not take Hitler for the Kremlin. gorski tapped into a rich vein of in- seriously, however, would concede Others who came to Germany cu- dividual stories that provide insight that his oratory skills and charisma rious about what was going on there into what it was like to work or travel would propel him into prominence. include the architect Philip Johnson, in Germany in the midst of these Nagorski looks at Charles Lind- the dancer Josephine Baker, a young seismic events. berg who was sent to Germany in Harvard student John F. Kennedy Many of the first-hand accounts 1936 to obtain intelligence on the and historian W.E.B. Dubois. in memoirs, correspondence and in- Luftwaffe. Karl Henry von Wiegand, Andy Nagorski is an award win- terviews were from journalists and the famed Hearst correspondent was ning journalist with a long career at diplomats. There were those who the first American reporter to meet Newsweek. -

Through the Hollywood Lens: the Vietnam War 3

Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at W&M Summer 2020 Through the Hollywood Lens: The Vietnam War Scott A. Langhorst, Ph.D. First Lieutenant 4th Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment 25th Division Tay Ninh, Vietnam (1969-70) Using Zoom tools - reminder • Use the menu bar (mouse over bottom/top of screen) to appear • Use icons to on menu bar open tools (click “on” click “off”) • Use “chat box” to ask questions or make comments • Use “participant” list for raising hand or other gestures • Make the session interactive by using the Zoom tools © Scott A. Langhorst, Ph.D. 1 Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at W&M Summer 2020 Questions or comments from last week? 1Lt Langhorst at FSB Rhode Island Forrest Gump (1994) • Directed by Robert Zemeckis • Won 6 Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Actor • Nominated for 7 other Oscars • Vietnam sequences filmed on Fripp Island, SC • Storyline: After many 1960’s adventures, Forrest joins the Army and goes to Vietnam. He makes a new friend, Bubba, who dies in his arms after an violent ambush. Forrest is able to save the rest of his squad and a reluctant Lt. Dan. Forrest comes home to an America that is divided, and saves a paraplegic Lt. Dan once again. He is a witness to the aftermath of Vietnam and the healing of America. © Scott A. Langhorst, Ph.D. 2 Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at W&M Summer 2020 What the movie got right • (Why “Forrest Gump” in a course about the Vietnam War?) • One film segment is about Forrest as a soldier in Vietnam (2/47 Inf. -

Oral History Interview with Sharon Huntley Kahn, July 10, 2018

Archives and Special Collections Mansfield Library, University of Montana Missoula MT 59812-9936 Email: [email protected] Telephone: (406) 243-2053 This transcript represents the nearly verbatim record of an unrehearsed interview. Please bear in mind that you are reading the spoken word rather than the written word. Oral History Number: 463-001 Interviewee: Sharon Huntley Kahn Interviewer: Donna McCrea Date of Interview: July 10, 2018 Donna McCrea: This is Donna McCrea, Head of Archives and Special Collections at the University of Montana. Today is July 10th of 2018. Today I'm interviewing Sharon Huntley Kahn about her father Chet Huntley. I'll note that the focus of the interview will really be on things that you know about Chet Huntley that other people would maybe not have known: things that have not been made public already or don't appear in many of the biographical materials and articles about him. Also, I'm hoping that you'll share some stories that you have about him and his life. So I'm going to begin by saying I know that you grew up in Los Angeles. Can you maybe start there and talk about your memories about your father and your time in L.A.? Sharon Kahn: Yes, Donna. Before we begin, I just want to say how nice it is to work with you. From the beginning our first phone conversations, I think at least a year and a half ago, you've always been so welcoming and interested, and it's wonderful to be here and I'm really happy to share inside stories with you. -

JFQ 31 JFQ▼ FORUM Sponds to Aggravated Peacekeeping in Joint Pub 3–0

0203 C2 & Pgs 1-3 3/3/04 9:07 AM Page ii The greatest lesson of this war has been the extent to which air, land, and sea operations can and must be coordinated by joint planning and unified command. —General Henry H. (“Hap”) Arnold Report to the Secretary of War Cover 2 0203 C2 & Pgs 1-3 3/27/04 7:18 AM Page iii JFQ Page 1—no folio 0203 C2 & Pgs 1-3 3/3/04 9:07 AM Page 2 CONTENTS A Word from the Chairman 4 by John M. Shalikashvili In This Issue 6 by the Editor-in-Chief Living Jointness 7 by William A. Owens Taking Stock of the New Joint Age 15 by Ike Skelton JFQ Assessing the Bottom-Up Review 22 by Andrew F. Krepinevich, Jr. JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY Living Jointness JFQ FORUM Bottom-Up Review Standing Up JFQ Joint Education Coalitions Theater Missle Vietnam Defense as Military History Standing Up Coalitions Atkinson‘s Crusade Defense Transportation 25 The Whats and Whys of Coalitions 26 by Anne M. Dixon 94 W93inter Implications for U.N. Peacekeeping A PROFESSIONAL MILITARY JOURNAL 29 by John O.B. Sewall PHOTO CREDITS The cover features an Abrams main battle tank at National Training Center (Military The Cutting Edge of Unified Actions Photography/Greg Stewart). Insets: [top left] 34 by Thomas C. Linn Operation Desert Storm coalition officers reviewing forces in Kuwait City (DOD), [bottom left] infantrymen fording a stream in Vietnam Preparing Future Coalition Commanders (DOD), [top right] students at the Armed Forces Staff College (DOD), and [bottom right] a test 40 by Terry J.