Center for Character & Leadership Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salute for the Ages D.C

GRADUATION DAY, 10 a.m., Saturday at Michie Stadium. Congratulations to the Class of 2010. OINTER IEW ® PVOL . 67, NO. 19 SERVING THE COMMUNITY OF WVE S T POINT , THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY MAY 20, 2010 New Supe nominated Huntoon chosen to be next academy leader WASHINGTON––Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates announced Tuesday that President Barack Obama has nominated Lt. Gen. David H. Huntoon, Jr. for reappointment to the rank of lieutenant general and assignment as the 58th Superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. A 1973 West Point graduate, Huntoon was commissioned in the infantry and, after attending Infantry Officer Basic, served with the 3rd Infantry Regiment (The Old Guard) at Fort Myer, Va. He later became commander of the regiment. He served with the 9th Division at Fort Lewis, Wash., the 3rd Infantry Division (Mechanized) in Germany and attended Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., and later became Deputy Commandant there. During Operations Just Cause and Desert Storm, he served with the XVIII Airborne Corps in Fort Bragg, N.C. He was the Commandant of the United States Army War College at Carlisle Barracks, Pa., and is currently serving as Director of the Army Staff, United States Army, Washington, Salute for the Ages D.C. Huntoon earned a master’s degree in Retired Gen. Ralph E. Haines, Jr., 96, accompanied by Cadet First Captain Tyler Gordy salute the “Father of the international relations from Georgetown Academy” Sylvanus Thayer at the foot of Thayer Statue during the annual alumni wreath-laying ceremony Tuesday University. -

WFLDP Leadership in Cinema – We Were Soldiers 2 of 10 Facilitator Reference

Facilitator Reference WE WERE SOLDIERS Submitted by: Pam McDonald .......................................................... E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 208-387-5318 Studio: Paramount .............................................................................................. Released: 2002 Genre: Drama ................................................................................................ Audience Rating: R Runtime: 138 minutes Materials VCR or DVD, television or projection system, Wildland Fire Leadership Values and Principles handouts (single-sided), Incident Response Pocket Guide (IRPG), notepad, writing utensil Objective Students will identify Wildland Fire Leadership Values and Principles illustrated within We Were Soldiers and discuss leadership lessons learned with group members or mentors. Basic Plot In 1965, 400 American troops faced an ambush by 2,000 enemy troops in the Ia Drang Valley (also known as the Valley of Death), in one of the most gruesome fights of the Vietnam War. We Were Soldiers is a detailed recreation of this true story: of the strategies, obstacles, and human cost faced by the troops that participated. The story focuses on the lieutenant colonel that led the attack, Hal Moore (Mel Gibson), and a civilian reporter who accompanied them, Joseph Galloway (Barry Pepper), as well as a number of other soldiers who were involved. (Taken from Rotten Tomatoes) We Were Soldiers is the story of a group that trained and sweated with one another—connected together in a way that only those who have shared similar settings can be—that entered into a chaotic situation, relied on one another for support and survival, and who eventually emerged— bruised and battered, but successful nonetheless. Set in war, the lesson is not about war, but about followership, leadership, and shared values. (From Paul Summerfelt, FFD-FMO, Flagstaff, AZ). -

Heirpower! Eight Basic Habits of Exceptionally Powerful Lieutenants

Heirpower! Eight Basic Habits of Exceptionally Powerful Lieutenants BOB VÁSQUEZ Chief Master Sergeant, USAF, Retired Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama June 2006 front.indd 1 7/17/06 3:22:50 PM Air University Library Cataloging Data Vásquez, Bob. Heirpower! : eight basic habits of exceptionally powerful lieutenants / Bob Vásquez. p. ; cm. ISBN 1-58566-154-6 1. Command of troops. 2. Leadership. I. Title. 355.33041––dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii front.indd 2 7/17/06 3:22:51 PM Contents Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . v ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii PREFACE . ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . xi INTRODUCTION . xiii Habit 1 Get a Haircut! First Impressions Last . 1 Habit 2 Shut Up! Listen and Pay Attention . 9 Habit 3 Look Up! Attitude Is Everything . 15 Habit 4 Be Care-Full! Take Care of Your Troops . 23 Habit 5 Sharpen the Sword! Take Care of Yourself First. 35 Habit 6 Be Good! Know Your Stuff . 45 Habit 7 Build Trust! Be Trustworthy . 51 Habit 8 Hang on Tight! Find an Enlisted Mentor . 59 FINAL THOUGHTS . 67 iii front.indd 3 7/17/06 3:22:51 PM THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Foreword Chief Bob Vásquez has found an innovative and effective way to share some basic principles that every new lieutenant should know on the subject of how to succeed as a leader in our great Air Force. -

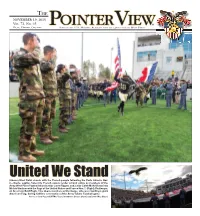

DPE Presents Lt. Gen. Hal Moore Award to First Class Cadets by Michelle Eberhart What Would That Be?” the West Point Assistant Editor Lt

NOVEMBER 19, 2015 1 THE NOVEMBER 19, 2015 VOL. 72, NO. 45 ® UTY ONOR OUNTRY OINTER IEW D , H , C PSERVING THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY AND THE COMMUNITY V OF WEST POINT ® United We Stand (Above) West Point stands with the French people following the Paris Attacks Nov. 6—liberté, égalité, fraternity. French cadets render a hand salute as members of the Army West Point Football team (senior Jared Rogers and junior Caleb McNeill) run into Michie Stadium with the fl ags of the United States and France Nov. 7. (Right) Challenger, an American Bald Eagle, fl ies above members of the Corps, who were holding a giant American Flag, during halftime ceremonies of the Army-Tulane Football game. PHOTOS BY JOHN PELLINO/DPTMS, VISUAL INFORMATION DIVISION (ABOVE) AND DANNY WILD (RIGHT) 2 NOVEMBER 19, 2015 NEWS & FEATURES POINTER VIEW MacShort Barracks RACISM & RESPECT renovation now complete Dear West Point community, By Matthew Talaber In light of recent events at the University of Missouri, Yale University Public Works Director and other colleges around the country, I’d like to talk for a moment about respect, our values and who we are as leaders in our profession. On Nov. 11, the Directorate of Public Works completed the At the heart of these events which have made national headlines are renovation of MacArthur Short Barracks. MacShort is the second racially insensitive and derogatory remarks and actions toward a particular of nine existing barracks to be renovated as part of Army’s Cadet group of students and institution’s perceived failure to properly address Barracks Upgrade Program. -

Hal Moore and Sergeant Major Plumley Are Based Together

CHARACTERISTICS Lieutenant Colonel Hal Moore and Sergeant Major Plumley are based together. They are Warriors and a Higher Command M16 Rifle team rated Fearless Veteran. They are an Independent Team. Lieutenant Colonel Hal Moore and Sergeant Major Plumley may join a Rifle Company (Air Mobile) for +50 points. GETTING PRETTY SPORTY DOWN HERE! THAT’S A NICE DAY! Moore and Plumley kept the battalion fighting despite seem- Plumley was an imposing figure on the battlefield. Often ingly impossible odds, and led them to victory. described as a veteran’s veteran, he never flinched, even as the enemy threatened to overrun the battalion HQ. Plumley Moore and any platoon he is currently leading, always passes simply pulled out his Colt .45 automatic pistol and stopped Motivation Tests on a roll of 3+. the enemy cold. FIRST TO SET FOOT ON THE FIELD When conducting Defensive Fire, Plumley uses his pistol to Moore firmly believed that he should be the first to step off defend himself and Moore. As a result, you may re-roll any the helicopter and the last to leave the battlefield in order to failed To Hit rolls by their team in Defensive Fire. Lieutenant Colonel provide the best leadership for his men during the fight. Any hits on Moore and Plumley do not count towards Pinning Moore and Plumley do not take up a box on the Helicopter Down the Platoon. Hal Moore Loading Chart when aboard a UH-1D Slick helicopter. They can be carried in addition to the helicopter’s normal passengers. Hal Moore was born in 1922 in Kentucky. -

Battlefieldleader Hal G

BATTLEFIELDLEADER HAL G. THE LEGACY AND LESSONS MOF AN AMERICANOORE WARRIOR BY BRIAN M. SOBEL ong before there was a best-selling book and a instantly recognized. He is ushered in to see the commanding major motion picture, Hal Moore was a name general wherever he travels. Young Soldiers and veterans alike familiar to those who studied military leadership. jump at the chance to meet him. He is admired by all who He was the steely-eyed, rock-ribbed young man know his story. who left his hometown of Bardstown, Kentucky, Hal Moore is a force of nature, with a penetrating intellect and L and went on to graduate from West Point, and courage to spare. At 82 years old, he is as busy as ever, spending then fight in Korea and Vietnam. By the end of his remarkable much of his time discussing leadership and lessons he learned in career, Moore achieved the rank of lieutenant general – and the heat of battle. For Moore, the discussions are not an academ- along the way he also became a legend. ic exercise, but a chance to impart information that will save Mention Hal Moore on any Army post and the name is lives. Perhaps he does this to spare even one family the news that 46 * ARMCHAIR GENERAL * SEPTEMBER 2004 model used by the U.S. Army for many years. years. many Armyfor U.S. model usedbythe o particularly combat danger- infantry –made canopy notcovered byjungle of anyarea –typical stands D inVietnam, commander, 3dBrigade Moore, Col. Hal us. The tent in the background, a “GP Small,” was a was a“GPSmall,” background, inthe tent us. -

Bruce Crandall

The Museum of Flight Oral History Collection The Museum of Flight Seattle, Washington Bruce Crandall Interviewed by: Ted Lehberger Date: August 24, 2017 Location: Seattle, Washington This interview was made possible with generous support from Mary Kay and Michael Hallman © The Museum of Flight 2017 2 Abstract: Vietnam War veteran and Medal of Honor recipient Bruce Perry Crandall is interviewed about his service as a pilot and engineer with the United States Army. He discusses his experiences conducting topographic studies during the 1950s and 1960s and his service as a helicopter pilot with the 1st Cavalry Division in Vietnam. Topics discussed include his training and service history, his mapping assignments in the Middle East and Central and South America, his participation in the battles of Ia Drang and Bong Son, and the circumstances surrounding the receipt of his Medal of Honor. Biography: Bruce Perry Crandall was born on February 7, 1933 in Olympia, Washington. His father was a United States Navy serviceman, and his mother worked as a welder at Todd Shipyards (Washington). After his parents divorced, his maternal grandmother helped to raise him and his siblings. Crandall attended Garfield Grade School, where he lettered in baseball, football, basketball and track. In high school, he was an All-American baseball player. At age 15, Crandall joined the Army National Guard in Olympia. After graduating high school in 1951, Crandall attended the University of Washington in the hopes of playing baseball as a sophomore. In 1953, he was drafted into the United States Army. He completed his basic training at Fort Lewis (Washington) and his advanced individual training in engineering at Fort Worden (Washington). -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Remarks On

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Remarks on Presenting the Presidential Citizens Medal to C. Richard Rescorla November 7, 2019 The President. Thank you very much. Please. Thank you. Great to be with you. And thank you all for being here. Today it's my honor to present an award reserved for those who perform exemplary deeds or acts of service for this great Nation and its citizens: the Presidential Citizens Medal. And it's a big deal. This evening we come together to pay tribute to a fallen hero who devoted his life to defending freedom and who made the supreme sacrifice to save others on September 11, 2001: Colonel Richard Rescorla. Richard was a great gentleman. He's looking down proudly on this wonderful family. And congratulations, this is a big evening. And it's great to have you at the White House because there's no place like it. Thank you. We are profoundly grateful to have with us Rick's beloved family. Please join me in welcoming his wife Susan—thank you, Susan—his son Trevor and his daughter Kim. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you. And to each of you—we cannot fathom all that you have endured, but today we express the gratitude of 329 million Americans. It's a lot of people. Rick was born in Cornwall, England, in 1939. As a boy, he met American soldiers preparing for the Normandy landing and dreamed of one day serving in uniform. It's a big thing for Rick. Soon, he had his chance and joined the British Army. -

The Bullwhip Squadron News ______

THE BULLWHIP SQUADRON NEWS ________________________________________________________________________ The official Newsletter of the Bullwhip Squadron Association Sept 1998 Adjutants Call The Adjutants Call for this newsletter will be a little different. I believe it is appropriate to remind all troopers of past history, when that history has impacted all of us so much. History is in the making of words and deeds, some by gallant troopers and some by not so gallant “others”. With that in mind, the following letter will serve as the starting point for this article and the reminder of a Gallant Trooper. Dear Loel, I have two items that I would like to bring to your attention. One is the last letter I received from Bullwhip-6. I don’t know why I kept it. I guess I was impressed at the statistics or it could easily have been because I admired this guy enough to follow him anywhere after the night I spent in LZ Betty, with several other troopers who survived solely on the strength of John B. Stockton’s intestinal fortitude. The other item is a date correction on SFC (Ret) Lionel Dela Rosa’s article concerning the Chu Pong Massif’s battle with “B” troop personnel. I can assure him that it was not the 20th of March but it was the 30th of March because I still remember the day very well as should John Ghere. I received wounds that day that kept me in Martin Army Hospital for over 22 months and eventually retirement. You guys are doing a super job on the Bullwhip Squadron News letter and Dela Rosa’s story could have been a missed number on the keyboard (and it was. -

The Road to My Lai

THE ROAD TO MY LAI HUMBOLDT STATE UNIVERSITY By George F. Shaw A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts In Sociology Summer, 2012 ABSTRACT The U.S. military of the Vietnam era was a total institution of the Goffman school, set apart from larger American society, whose often forcibly inducted personnel underwent a transformative process from citizen to soldier. Comprised of a large group of individuals, with a common purpose, with a clear distinction between officers and enlisted, and regulated by a single authority, Goffman’s formulation as presented in the 1950’s has become a basic tenet of military sociology. The overwhelming evidence is clear: perhaps the best equipped army in history faced a debacle on the battlefield and cracked under minimal stress due to the internal rotation structure which was not resolved until the withdrawal of U.S. forces: the “fixed length tour”. Throughout the Vietnam War the duration of the tour in the combat theater was set at 12 months for Army enlisted, 13 months for Marine enlisted - officer ranks in both branches served six months in combat, six months on staff duty. The personnel turbulence generated by the “fixed length” combat tour and the finite Date of Estimated Return from Overseas (DEROS) created huge demands for replacement manpower among both enlisted and junior grade officers at the company and platoon level. It has been argued that just as a man was learning the ropes of combat in the jungles of Vietnam he was rotated out of the theater of operations. -

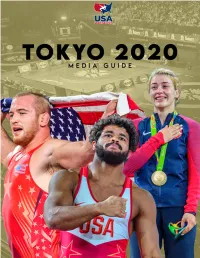

Themat.Com | @Usawrestling | #Tokyo2020 1 Table of Contents

themat.com | @usawrestling | #Tokyo2020 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Info 3 Schedule & press info 4-5 U.S. Team preview Greco-Roman 7 Roster 8 Expected field 9-14 Bios & previews Women’s freestyle 16 Roster 17 Expected field 18-23 Bios & previews Men’s freestyle 25 Roster 26 Expected field 27-32 Bios & previews Coaches 34 Greco-Roman 35 Women’s freestyle 36 Men’s freestyle 2020 USA Wrestling Tokyo Olympics Media Guide Credits Team Leaders 38 Bios The 2020 USA Wrestling Tokyo Olympics media guide was edited and designed by Taylor Miller. Special History thanks to USA Wrestling communications staff Mike 40-44 World and Olympic records Willis and Gary Abbott. Photos by Tony Rotundo. themat.com | @usawrestling | #Tokyo2020 2 SCHEDULE & PRESS iNFO 2020 TOKYO OLYMPIC GAMES USOPC WRESTLING PRESS OFFICERS at Tokyo, Japan (Aug. 1-7, 2021) Gary Abbott Sunday, Aug. 1 Email - [email protected] 11 a.m. – Qualification rounds (GR 60, 130; WFS 76 kg) Phone number - +1 719-659-9637 6:15 p.m. – Semifinals (GR 60, 130; WFS 76 kg) Monday, Aug. 2 11 a.m. – Qualification rounds (GR 77, 97; WFS 68 kg) Taylor Miller 11 a.m. – Repechage (GR 60, 130; WFS 76 kg) Email - [email protected] 6:15 p.m. – Semifinals (GR 77, 97; WFS 68 kg) Phone number - +1 405-420-8622 7:30 p.m. - Finals (GR 60, 130; WFS 76 kg) Tuesday, Aug. 3 11 a.m. – Qualification rounds (GR 67, 87; WFS 62 kg) Updates on the Olympic Wrestling competition will 11 a.m. – Repechage (GR 77, 97; WFS 68 kg) be provided on TeamUSA.org as well as on USA 6:15 p.m. -

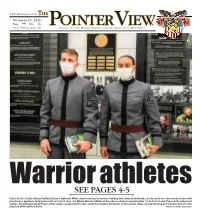

WEST POINT MWR CALENDAR Westpoint.Armymwr.Com

NOVEMBER 19, 2020 1 WWW.WESTPOINT.EDU THE NOVEMBER 19, 2020 VOL. 77, NO. 45 OINTER IEW® DUTY, HONOR, COUNTRY PSERVING THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY AND THE COMMUNITY V OF WEST POINT ® WarriorSEE PAGES athletes 4-5 • • Class of 2021 Cadets Beaux Guff ey (left) and Gabrielle White stand next to one another, holding their awards and books, as the audience commended them with thunderous applause during the ninth annual Lt. Gen. Hal Moore Warrior Athlete of Excellence Award ceremony Nov. 12 at Arvin Cadet Physical Development Center. The Department of Physical Education recognized the two cadets for living by the tenets of the warrior ethos and performing at the highest level in the physical pillar at West Point. Photo by Jorge Garcia/PV 2 NOVEMBER 19, 2020 NEWS & FEATURES POINTER VIEW Weathering winter: Preparedness is key By Thomas Slater a Code White or Code Red or to have no change time. So too, those who have approved Tele- During adverse weather conditions, West Emergency Preparedness Specialist, to normal operations.” work agreements are expected to work. Point employees can obtain weather, road Directorate of Plans, Training, Based on the facts presented, Rosel makes Personnel not identifi ed as weather essential or conditions and operations information by calling Mobilization and Security the decision whether or not to implement USMA on approved Tele-work agreements, and those 938-7000 or looking for announcements on the Policy 40-03, Leave During Adverse Weather. who are not already on leave, will not be charged Command Information Channel 8 or 23. Peggy, Quade, Roland and Shirley are If possible, the decision to modify the hours leave for the Code Red period.