Home Movie Night HFF May 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Qicx6.Ebook] Khrushchev Pdf Free](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3465/qicx6-ebook-khrushchev-pdf-free-23465.webp)

[Qicx6.Ebook] Khrushchev Pdf Free

QIcx6 (Online library) Khrushchev Online [QIcx6.ebook] Khrushchev Pdf Free Edward Crankshaw *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks #3905982 in Books 2016-03-08 2016-03-08Formats: Audiobook, MP3 Audio, UnabridgedOriginal language:EnglishPDF # 1 6.75 x .50 x 5.25l, Running time: 11 HoursBinding: MP3 CD | File size: 79.Mb Edward Crankshaw : Khrushchev before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Khrushchev: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. This is a very readable book due to the style ...By Charles W. RiendeauThis is a very readable book due to the style of the author. But, it is also one of least fact-based biographies I have ever read. Partly this is due to the time in which it was written ( c 1966) when acquiring information not "officially" released by the Soviet Union was very, very hard. It was, for its time, I suppose what was available. In this time, I would suggest biographies of Khrushchev that were written in the early 90s when access to the KGB files and public records will have allowed the author to gather a more comprehensive set of facts.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Good historical readBy ceharvYou really cannot understand the full scope of 20th century history without understanding Russia. This book is a very interesting read about someone who, at a minimum, lead a very interesting life in a very interesting time. The pace is quick and the history important and puts much of our (in the U.S.) history in perspective. -

Malcolm Muggeridge the Infernal Grove

e FONTANA MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE THE INFERNAL GROVE 'The wit sparkles on almost every page' BERNARD LEVIN Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 2 The Infernal Grove Malcolm Muggeridge was born in 1903 and educated at Selhurst Grammar School and Selwyn College, Cambridge. After lecturing at the Egyptian University in Cairo, he joined the editorial staff of the Man chester Guardian in 1930, and was Moscow Corre spondent for this paper from 1932-3. In the war of 1939-45 he served as an Intelligence officer in North Africa, Moz.ambique, Italy and France, being seconded to MI6, the wartime version of the Secret Service. He ended up in Paris as Liaison Officer with the French Securite Militaire, and was awarded the Legion of Hon0ur (Chevalier), the Croix de Guerre with Palm and the Medaille de la Reconnaissance Fran9aise. His career as a journalist included a spell' as Washington Correspondent of the Daily Telegraph from 1946-7, and Deputy Editorship from 1950-52. He was Editor of Punch from 1953-7 and Rector of Edinburgh University from 1967-8. He has written numerous books since the early '30s, including Some thing Beautiful for God, Jesus Rediscovered, Tread Softly for you Tread on my Jokes, and The Thirties. He lives in Robertsbridge, Sussex. Volume I of Chronicles of Wasted Time, The Green Stick, is abo available from Fontana, MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 2 The Infernal Grove Till I tum from Female Love, And root up the Infernal Grove, I shall never worthy be To step into Eternity Blake FONTA NA/Collins First published by William Collins Sons & Co. -

Streams of Civilization: Volume 2

Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press i Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 1 8/7/17 1:24 PM ii Streams of Civilization Volume Two Streams of Civilization, Volume Two Original Authors: Robert G. Clouse and Richard V. Pierard Original copyright © 1980 Mott Media Copyright to the first edition transferred to Christian Liberty Press in 1995 Streams of Civilization, Volume Two, Third Edition Copyright © 2017, 1995 Christian Liberty Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without written permission from the publisher. Brief quota- tions embodied in critical articles or reviews are permitted. Christian Liberty Press 502 West Euclid Avenue Arlington Heights, Illinois 60004-5402 www.christianlibertypress.com Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press Revised and Updated: Garry J. Moes Editors: Eric D. Bristley, Lars R. Johnson, and Michael J. McHugh Reviewers: Dr. Marcus McArthur and Paul Kostelny Layout: Edward J. Shewan Editing: Edward J. Shewan and Eric L. Pfeiffelman Copyediting: Diane C. Olson Cover and Text Design: Bob Fine Graphics: Bob Fine, Edward J. Shewan, and Lars Johnson ISBN 978-1-629820-53-8 (print) 978-1-629820-56-9 (e-Book PDF) Printed in the United States of America Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 2 8/7/17 1:24 PM iii Contents Foreword ................................................................................1 Introduction ...........................................................................9 Chapter 1 European Exploration and Its Motives -

Wilson, MI5 and the Rise of Thatcher Covert Operations in British Politics 1974-1978 Foreword

• Forward by Kevin McNamara MP • An Outline of the Contents • Preparing the ground • Military manoeuvres • Rumours of coups • The 'private armies' of 1974 re-examined • The National Association for Freedom • Destabilising the Wilson government 1974-76 • Marketing the dirt • Psy ops in Northern Ireland • The central role of MI5 • Conclusions • Appendix 1: ISC, FWF, IRD • Appendix 2: the Pinay Circle • Appendix 3: FARI & INTERDOC • Appendix 4: the Conflict Between MI5 and MI6 in Northern Ireland • Appendix 5: TARA • Appendix 6: Examples of political psy ops targets 1973/4 - non Army origin • Appendix 7 John Colin Wallace 1968-76 • Appendix 8: Biographies • Bibliography Introduction This is issue 11 of The Lobster, a magazine about parapolitics and intelligence activities. Details of subscription rates and previous issues are at the back. This is an atypical issue consisting of just one essay and various appendices which has been researched, written, typed, printed etc by the two of us in less than four months. Its shortcomings should be seen in that light. Brutally summarised, our thesis is this. Mrs Thatcher (and 'Thatcherism') grew out of a right-wing network in this country with extensive links to the military-intelligence establishment. Her rise to power was the climax of a long campaign by this network which included a protracted destabilisation campaign against the Liberal and Labour Parties - chiefly the Labour Party - during 1974-6. We are not offering a conspiracy theory about the rise of Mrs Thatcher, but we do think that the outlines of a concerted campaign to discredit the other parties, to engineer a right-wing leader of the Tory Party, and then a right-wing government, is visible. -

Transatlantic Brinksmanship: the Anglo-American

TRANSATLANTIC BRINKSMANSHIP: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN ALLIANCE AND CONSERVATIVE IDEOLOGY, 1953-1956 by DAVID M. WATRY Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON December 2011 Copyright © by David M. Watry 2011 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people have helped me in the preparation of this dissertation. I wish to personally thank and acknowledge Dr. Joyce S. Goldberg, who chaired the dissertation committee. Without her support, encouragement, and direction, this project would have been impossible. Dr. Goldberg fought for this dissertation in many ways and went far beyond the call of duty. I will be forever in her debt and forever grateful for her expertise, passion, patience, and understanding. I also wish to thank the other members of my dissertation committee, Dr. Kenneth R. Philp and Dr. Stanley H. Palmer. Their critiques, evaluations, and arguments made my dissertation a much more polished product than what it would have been without their significant help. Their wealth of knowledge and expertise made the writing of the dissertation a pleasurable experience. I would also like to thank the Dean of Liberal Arts, Dr. Beth Wright, the Associate Dean, Dr. Kim Van Noort, and Assistant Dean, Dr. Eric Bolsterli for providing me with the Dean’s Excellence Award for Graduate Research Travel. With this award, I was able to travel overseas to do research in London, Cambridge, Oxford, and Birmingham. Moreover, I wish to thank Dr. Robert B. Fairbanks, the former Chairman of the History Department at the University of Texas at Arlington. -

The German Fear of Russia Russia and Its Place Within German History

The German Fear of Russia Russia and its place within German History By Rob Dumont An Honours Thesis submitted to the History Department of the University of Lethbridge in partial fulfillment of the requirements for History 4995 The University of Lethbridge April 2013 Table of Contents Introduction 1-7 Chapter 1 8-26 Chapter 2 27-37 Chapter 3 38-51 Chapter 4 39- 68 Conclusion 69-70 Bibliography 71-75 Introduction In Mein Kampf, Hitler reflects upon the perceived failure of German foreign policy regarding Russia before 1918. He argues that Germany ultimately had to prepare for a final all- out war of extermination against Russia if Germany was to survive as a nation. Hitler claimed that German survival depended on its ability to resist the massive faceless hordes against Germany that had been created and projected by Frederick the Great and his successors.1 He contends that Russia was Germany’s chief rival in Europe and that there had to be a final showdown between them if Germany was to become a great power.2 Hitler claimed that this showdown had to take place as Russia was becoming the center of Marxism due to the October Revolution and the founding of the Soviet Union. He stated that Russia was seeking to destroy the German state by launching a general attack on it and German culture through the introduction of Leninist principles to the German population. Hitler declared that this infiltration of Leninist principles from Russia was a disease and form of decay. Due to these principles, the German people had abandoned the wisdom and actions of Frederick the Great, which was slowly destroying German art and culture.3 Finally, beyond this expression of fear, Hitler advocated that Russia represented the only area in Europe open to German expansion.4 This would later form the basis for Operation Barbarossa and the German invasion of Russia in 1941 in which Germany entered into its final conflict with Russia, conquering most of European 1 Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans Ralph Manheim (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1943, originally published 1926), 197. -

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: from Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare By

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: From Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare by Matthew A. Bellamy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2018 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Najita, Chair Professor Daniel Hack Professor Mika Lavaque-Manty Associate Professor Andrea Zemgulys Matthew A. Bellamy [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6914-8116 © Matthew A. Bellamy 2018 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all my students, from those in Jacksonville, Florida to those in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is also dedicated to the friends and mentors who have been with me over the seven years of my graduate career. Especially to Charity and Charisse. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ii List of Figures v Abstract vi Chapter 1 Introduction: Espionage as the Loss of Agency 1 Methodology; or, Why Study Spy Fiction? 3 A Brief Overview of the Entwined Histories of Espionage as a Practice and Espionage as a Cultural Product 20 Chapter Outline: Chapters 2 and 3 31 Chapter Outline: Chapters 4, 5 and 6 40 Chapter 2 The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 1: Conspiracy, Bureaucracy and the Espionage Mindset 52 The SPECTRE of the Many-Headed HYDRA: Conspiracy and the Public’s Experience of Spy Agencies 64 Writing in the Machine: Bureaucracy and Espionage 86 Chapter 3: The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 2: Cruelty and Technophilia -

“Creating Many Ripples” Homily for 23 Sunday of Ordinary Time

1 “Creating many Ripples” Homily for 23rd Sunday of Ordinary Time September 4th 2016 Wisdom of Solomon 9:13–18b Psalm 90:3–6, 12–17 Philemon 9–10, 12–17 Gospel Luke 14:25–33 In December 1982 Malcolm Muggeridge became a Roman Catholic. What made this event so significant was the fact that for much of his life, he was either an atheist, in his younger years, or an agnostic, during midlife. He was born in 1903 and was received into the Church at age 79. With the passing of the years he came to have a greater respect for Christianity but because of his love for the deadly sins, especially pride, gluttony and lust he did not think he could rightly represent the Christian faith and so did not convert. By the nineteen fifties he was one of the best known British journalists in the world, a status that increased even more after the advent of TV. In the late sixties he went to Kolkata to meet Mother Theresa. Instead of being angry, Muggeridge’s heart melted as Mother Teresa forced him to wait for hours while she tended to the sick and the dying. Instead of having to fend off the intensity of this tiny nun’s love for the poorest of the poor, he embraced her indelibly by writing Something Beautiful for God. After his conversion Muggeridge remembered Mother Teresa of Kolkata, whose selfless work for India’s destitute he first told the world about, had a dramatic transforming effect on his life. Seeing the light of God illuminate the nun’s wizened face, seeing her complete trust in God, Muggeridge saw as never before “the pathetic condition of his worldly cynicism”. -

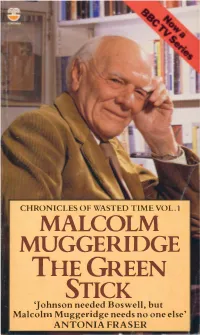

MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE THEGREEN STICK 'Johnson Needed Boswell, but Malcolm Muggeridge Needs No One Else' ANTONIA FRASER Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 1

CHRONICLES OF WASTED TIME VOL.1 MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE THEGREEN STICK 'Johnson needed Boswell, but Malcolm Muggeridge needs no one else' ANTONIA FRASER Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 1 The Green Stick Malcolm Muggeridge was born in 1903 and educated . at Selhurst Grammar School and Selwyn College, Cambridge. After lecturing at the Egyptian University in Cairo, he joined the editorial staff of the Man chester Guardian in 1930, and was Moscow Corre spondent for this paper from 1932-3. In the war of 1939-45 he served as an Intelligence. officer in North Africa, Mozambique, Italy and France, being seconded to M I6, the wartime version of the Secret Service. He ended up in Paris as Liaison Officer with the French Securite Militaire, and was awarded the Legion of Honour (Chevalier), the Croix de Guerre with Palm and the Medaille de la Reconnaissance Frani;:aise. His career as a journalist included a spell as Washington Correspondent of the Daily Telegraph from 1946-7, and Deputy Editorship from 1950-52. He was Editor of Punch from 1953-7 and Rectm of Edinburgh University from 1967-8. He has written numerous books since the early '30s, including Some thing Beautiful for God, Jesus Rediscovered, Tread Softly for you Tread on my Jokes, and The Thirties. He lives in Robertsbridge, Sussex. MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE Chronicles of Wasted Time Part I The Green Stick I used to believe that there was a green stick, buried on the edge of a ravine in the old Zakaz forest at Yasnaya Polyana, on which words were carved that would destroy all the evil in the hearts of men and bring them everything good. -

MI6: Fifty Years of Special Operations

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Huddersfield Repository University of Huddersfield Repository Dorril, Stephen A Critical Review: MI6: Fifty years of special operations Original Citation Dorril, Stephen (2010) A Critical Review: MI6: Fifty years of special operations. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/9763/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ University of Huddersfield PhD by Publication STEPHEN DORRIL A Critical Review: MI6: FIFTY YEARS OF SPECIAL OPERATIONS Presented December 2010 1 I would like to thank Professor Keith Laybourn for his welcome comments and generous support during the writing of this review. - Stephen Dorril 2 CONTENTS 1. THE REVIEW page 4 to page 40 - Introduction page 4 to page 8 - Methodology and Research page 9 to page 25 - Contents page 26 to page 35 - Impact page 36 to page 40 - Conclusion page 41 to page 42 2. -

Ethical Record

The ISSN 0014- 1690 Ethical Record Vol. 96 No. 9 OCTOBER 1991 CONTENTS Page Saint Mugg 3 Relation between Brain vc Consciousness 7 Book Review 12 Letters 14 London Student Skeptics 15 Forthcoming Events 16 Editorial This issue of The Ethical Record is unusually Perhaps the strongest reason for retaining short due to an absence of suitable material. the present title is that of tradition. But this is Due to the economics and technology of no reason at all. It is simply to say that things printing the journal must be in increments of have always been thus, so they must remain 8 pages. so. Even if it were the case that a particular usage had always been so this would not of Three years ago Nicolas Walter suggested itself be a good enough reason for retaining it. that it was time to consider changing the But such appeals to tradition usually arbitrarily name of the South Place Ethical Society ('A stop in historical reference at the moment Century of the Ethical Movement', ER, when that particular usage itself became September '88). This suggestion seemed to current. This is so in the case of the present elicit little response. I will repeat this proposal name for the Society. It was not always called and invite readers to reply: by its present name and need not continue to The premises of the Society are no longer be so. -at South Place, so 'South Place' is no longer an accurate qualification of 'Ethical Society'. But then again: surely the 'it' itself has changed. -

1 “Making Voices Heard…”: Index on Censorship As Advocacy

‘Making voices heard …’: index on censorship as advocacy journalism Item Type Article Authors Steel, John Citation Steel, J. (2018). 'Making voices heard…': Index on Censorship as Advocacy Journalism'. Journalism, pp. 1-30. DOI 10.1177/1464884918760866 Publisher Sage Journal Journalism, Theory, Practice and Criticism Rights CC0 1.0 Universal Download date 27/09/2021 12:23:01 Item License http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/625225 “Making voices heard…”: Index on Censorship as advocacy journalism1 John Steel University of Sheffield, UK Abstract The magazine Index on Censorship has sought, since its launch in 1972, to provide a space where censorship and abuses against freedom of expression have been identified, highlighted and challenged. Originally set up by a collection of writers and intellectuals who were concerned at the levels of state censorship and repression of artists in and under the influence of the Soviet Union and elsewhere, ‘Index’ has provided those championing the values of freedom of expression with a platform for highlighting human rights abuses, curtailment of civil liberties and formal and informal censorship globally. Charting its inception and development between 1971 and 1974, the paper is the first to situate the journal within the specific academic literature on activist media (Janowitz, 1975; Waisbord, 2009; Fisher, 2016). In doing so the paper advances an argument which draws on the drivers and motivations behind the publication’s launch to signal the development of a particular justification or ‘advocacy’ of a left-libertarian civic model of freedom of speech. Introduction This paper examines the foundation and formative ideas behind and expressed within the publication Index on Censorship (hereafter cited as Index).