Gandhi and Tolstoy. a Study of Gandhi's Intellectual Development Considered Within the Framev,Ork of Hermeneutic Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi Warrior of Non-Violence P

SATYAGRAHA IN ACTION Indians who had spent nearly all their lives in South Africi Gandhi was able to get assistance for them from South India an appeal was made to the Supreme Court and the deportation system was ruled illegal. Meantime, the satyagraha movement continued, although more slowly as a result of government prosecution of the Indians and the animosity of white people to whom Indian merchants owed money. They demanded immediate payment of the entire sum due. The Indians could not, of course, meet their demands. Freed from jail once again in 1909, Gandhi decided that he must go to England to get more help for the Indians in Africa. He hoped to see English leaders and to place the problems before them, but the visit did little beyond acquainting those leaders with the difficulties Indians faced in Africa. In his nearly half year in Britain Gandhi himself, however, became a little more aware of India’s own position. On his way back to South Africa he wrote his first book. Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule. Written in Gujarati and later translated by himself into English, he wrote it on board the steamer Kildonan Castle. Instead of taking part in the usual shipboard life he used a packet of ship’s stationery and wrote the manuscript in less than ten days, writing with his left hand when his right tired. Hind Swaraj appeared in Indian Opinion in instalments first; the manuscript then was kept by a member of the family. Later, when its value was realized more clearly, it was reproduced in facsimile form. -

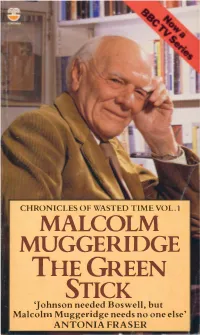

Malcolm Muggeridge the Infernal Grove

e FONTANA MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE THE INFERNAL GROVE 'The wit sparkles on almost every page' BERNARD LEVIN Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 2 The Infernal Grove Malcolm Muggeridge was born in 1903 and educated at Selhurst Grammar School and Selwyn College, Cambridge. After lecturing at the Egyptian University in Cairo, he joined the editorial staff of the Man chester Guardian in 1930, and was Moscow Corre spondent for this paper from 1932-3. In the war of 1939-45 he served as an Intelligence officer in North Africa, Moz.ambique, Italy and France, being seconded to MI6, the wartime version of the Secret Service. He ended up in Paris as Liaison Officer with the French Securite Militaire, and was awarded the Legion of Hon0ur (Chevalier), the Croix de Guerre with Palm and the Medaille de la Reconnaissance Fran9aise. His career as a journalist included a spell' as Washington Correspondent of the Daily Telegraph from 1946-7, and Deputy Editorship from 1950-52. He was Editor of Punch from 1953-7 and Rector of Edinburgh University from 1967-8. He has written numerous books since the early '30s, including Some thing Beautiful for God, Jesus Rediscovered, Tread Softly for you Tread on my Jokes, and The Thirties. He lives in Robertsbridge, Sussex. Volume I of Chronicles of Wasted Time, The Green Stick, is abo available from Fontana, MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 2 The Infernal Grove Till I tum from Female Love, And root up the Infernal Grove, I shall never worthy be To step into Eternity Blake FONTA NA/Collins First published by William Collins Sons & Co. -

Ahimsa Center- K-12 Teacher Institute Lesson Plan Title of Lesson: Gandhi's Voice: Writing As Nonviolent Resistance Lesson B

Ahimsa Center- K-12 Teacher Institute Lesson Plan Title of Lesson: Gandhi’s Voice: Writing as Nonviolent Resistance Lesson By: Rebecca Eastman Grade Level/ Subject Areas: Class Size: Time/ Duration of Lessons: Grade Eight, English 20-30 students Lesson one of two Language Arts 1 hour Objectives of Lesson: • Students will identify how Mahatma Gandhi used writing as a means of nonviolent communication, as a means to communicate nonviolence, and as a necessary tool for reflection and self development. • Students will record with 80% accuracy, the genre, writing style, content and effect of two pieces of writing, one narrative and one expository. Lesson Abstract: In this lesson, eighth grade English Language Arts students will be introduced to M. K. Gandhi, not only as a nonviolent activist, but as a writer. After watching a short film on Gandhi as a writer, they will explore two excerpts of Gandhi’s writing, one narrative and the other expository. Students will identify the characteristics of what can make writing a nonviolent form of activism. Using a graphic organizer, students will work in groups to dissect Gandhi’s writing, categorizing the theme, similarities and differences, and effect of these excerpts. This and future lessons in the unit stress the importance of using one’s voice for social change. Lesson Content: Before the world knew Gandhi as one of the most influential persons of the 20th Century. Before he became a spiritual leader for India and the world, Gandhi was a man who wrote. Mohandas K. Gandhi was born in India in 1869, as a teen lived in England, as a young adult, South Africa and then back to India for the remainder of his life. -

Streams of Civilization: Volume 2

Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press i Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 1 8/7/17 1:24 PM ii Streams of Civilization Volume Two Streams of Civilization, Volume Two Original Authors: Robert G. Clouse and Richard V. Pierard Original copyright © 1980 Mott Media Copyright to the first edition transferred to Christian Liberty Press in 1995 Streams of Civilization, Volume Two, Third Edition Copyright © 2017, 1995 Christian Liberty Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without written permission from the publisher. Brief quota- tions embodied in critical articles or reviews are permitted. Christian Liberty Press 502 West Euclid Avenue Arlington Heights, Illinois 60004-5402 www.christianlibertypress.com Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press Revised and Updated: Garry J. Moes Editors: Eric D. Bristley, Lars R. Johnson, and Michael J. McHugh Reviewers: Dr. Marcus McArthur and Paul Kostelny Layout: Edward J. Shewan Editing: Edward J. Shewan and Eric L. Pfeiffelman Copyediting: Diane C. Olson Cover and Text Design: Bob Fine Graphics: Bob Fine, Edward J. Shewan, and Lars Johnson ISBN 978-1-629820-53-8 (print) 978-1-629820-56-9 (e-Book PDF) Printed in the United States of America Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 2 8/7/17 1:24 PM iii Contents Foreword ................................................................................1 Introduction ...........................................................................9 Chapter 1 European Exploration and Its Motives -

Leo Tolstoy Correspondence Date: 1909, October 01 Day: Friday Today’S Itinerary: London

Mahatma Gandhi and Leo Tolstoy Correspondence Date: 1909, October 01 Day: Friday Today’s Itinerary: London. Today’s Details: LETTER TO LEO TOLSTOY I take the liberty of inviting your attention to what has been going on in the Transvaal (South Africa) for nearly three years. There is in that Colony a British Indian population of nearly 13,000. These Indians have, for several years, laboured under various legal disabilities. The prejudice against colour and in some respects against Asiatics is intense in that Colony. It is largely due, so far as Asiatics are concerned, to trade jealousy. The climax was reached three years ago, with a law which I and many others considered to be degrading and calculated to unman those to whom it was applicable. I felt that submission to a law of this nature was inconsistent with the spirit of true religion. I and some of my friends were and still are firm believers in the doctrine of non-resistance to evil. I had the privilege of studying your writings also, which left a deep impression on my mind. British Indians, before whom the position was fully explained, accepted the advice that we should not submit to the legislation, but that we should suffer imprisonment, or whatever other penalties the law may impose for its breach. The result has been that nearly one-half of the Indian population, that was unable to stand the heat of the struggle, to suffer the hardships of imprisonment, have withdrawn from the Transvaal rather than submit to [the] law which they have considered degrading. -

Formative Years

CHAPTER 1 Formative Years Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, a seaside town in western India. At that time, India was under the British raj (rule). The British presence in India dated from the early seventeenth century, when the English East India Company (EIC) first arrived there. India was then ruled by the Mughals, a Muslim dynasty governing India since 1526. By the end of the eighteenth century, the EIC had established itself as the paramount power in India, although the Mughals continued to be the official rulers. However, the EIC’s mismanagement of the Indian affairs and the corruption among its employees prompted the British crown to take over the rule of the Indian subcontinent in 1858. In that year the British also deposed Bahadur Shah, the last of the Mughal emperors, and by the Queen’s proclamation made Indians the subjects of the British monarch. Victoria, who was simply the Queen of England, was designated as the Empress of India at a durbar (royal court) held at Delhi in 1877. Viceroy, the crown’s representative in India, became the chief executive-in-charge, while a secretary of state for India, a member of the British cabinet, exercised control over Indian affairs. A separate office called the India Office, headed by the secretary of state, was created in London to exclusively oversee the Indian affairs, while the Colonial Office managed the rest of the British Empire. The British-Indian army was reorganized and control over India was established through direct or indirect rule. The territories ruled directly by the British came to be known as British India. -

The Diary As “The Mirror of the Self”

Chapter 4: The Diary as “The Mirror of the self” Vashna Jagarnath Rhodes University History Department Draft: Paper for WISH Seminar Chapter Four The Diary as “The Mirror of the self ”1 The primary focus of this chapter is to illustrate the impact that the daily writing practice of keeping a diary had on the development of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's philosophical and political practices. Although Gandhi had been a diarist for most of his adult life this chapter only examines a particular set of diaries related to his time in Natal and Transvaal. Gandhi began diary writing as an occasional activity but by the end of his life it had became integral to his daily writing practices. Once he had established his daily writing routine he also encouraged his political followers in South Africa to do the same.2 Many years later, in India, Gandhi also required his satyagrahis to keep a daily diary which he read. There are sixty four diary entry titles in the table of contents of the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (CWMG). It needs to be noted, however, that not all these entries are full diary entries. For example there are only twenty pages of the first diary that he wrote on his inbound trip to London are available. Whereas his second diary, written on his return to India for The Vegetarian, and his Vital Foods diary, which was also written for The Vegetarian, are complete. However both these diaries were only a few pages in length as the diaries only lasted the duration of the voyage and the dietary experiment respectively. -

Tolstoy and Cosmopolitanism

CHAPTER 8 Tolstoy and Cosmopolitanism Christian Bartolf Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) is known as the famous Russian writer, author of the novels Anna Karenina, War and Peace, The Kreutzer Sonata, and Resurrection, author of short prose like “The Death of Ivan Ilyich”, “How Much Land Does a Man Need”, and “Strider” (Kholstomer). His literary work, including his diaries, letters and plays, has become an integral part of world literature. Meanwhile, more and more readers have come to understand that Leo Tolstoy was a unique social thinker of universal importance, a nineteenth- and twentieth-century giant whose impact on world history remains to be reassessed. His critics, descendants, and followers became almost innu- merable, among them Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in South Africa, later called “Mahatma Gandhi”, and his German-Jewish architect friend Hermann Kallenbach, who visited the publishers and translators of Tolstoy in England and Scotland (Aylmer Maude, Charles William Daniel, Isabella Fyvie Mayo) during the Satyagraha struggle of emancipation in South Africa. The friendship of Gandhi, Kallenbach, and Tolstoy resulted in an English-language correspondence which we find in the Collected Works C. Bartolf (*) Gandhi Information Center - Research and Education for Nonviolence (Society for Peace Education), Berlin, Germany © The Author(s) 2018 121 A.K. Giri (ed.), Beyond Cosmopolitanism, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-5376-4_8 122 C. BARTOLF of both, Gandhi and Tolstoy, and in the Tolstoy Farm as the name of the second settlement project of Gandhi -

Times-NIE-Web-Ed-AUGUST 14-2021-Page3.Qxd

CELLULAR JAIL, ANDAMAN & BIRLA HOUSE: Birla House is a muse- NICOBAR ISLANDS: Also known as um dedicated to Mahatma Gandhi. It ‘Kala Pani’, the British used the is the location where Gandhi spent CELEBRATING FREEDOM jail to exile political prisoners at the last 144 days of his life and was SATURDAY, AUGUST 14, 2021 03 this colonial prison assassinated on January 30, 1948 CLICK HERE: PAGE 3 AND 4 Pre-Independence slogans and its relevance in India today Slogans raised by leaders during the freedom movement set the mood of the nation’s revolution for its independence. They epitomised the struggle and hopes of millions of Indians. Author and former ad guru ANUJA CHAUHAN revisits these powerful slogans and explains their history and relevance in a contemporary India SATYAMEV JAYATE QUIT INDIA LIKE SWARAJ, KHADI IS (Truth alone triumphs) HISTORY: This slogan is widely associ- OUR BIRTH-RIGHT ated with Mahatma Gandhi (what he HISTORY: Inscribed at the base of started was the Quit India Movement India’s national emblem, this phrase is from August 8, 1942, in Bombay (then), a mantra from the ancient Indian scr- but the term ‘Quit India’ was actually ipture, ‘Mundaka Upanishad’, which coined by a lesser-known hero of was popularised by freedom fighter India’s freedom struggle – Yusuf Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya during Meherally. He had published a booklet India’s freedom movement. titled ‘Quit India’ (sold in weeks) and got over a thousand ‘Quit India’ badges to give life to the slogan that Gandhi also started using and popularised. ‘YOUNGSTERS, DON’T QUIT INDIA’: Quit India was a powerful slogan and HISTORY: Mahatma Gandhi’s call to as a slogan) was written by Urdu the jingle of an epic movement meant use khadi became a movement for poet Muhammad Iqbal in 1904 for to drive the British away from our the indigenous swadeshi (Indian) children. -

“Creating Many Ripples” Homily for 23 Sunday of Ordinary Time

1 “Creating many Ripples” Homily for 23rd Sunday of Ordinary Time September 4th 2016 Wisdom of Solomon 9:13–18b Psalm 90:3–6, 12–17 Philemon 9–10, 12–17 Gospel Luke 14:25–33 In December 1982 Malcolm Muggeridge became a Roman Catholic. What made this event so significant was the fact that for much of his life, he was either an atheist, in his younger years, or an agnostic, during midlife. He was born in 1903 and was received into the Church at age 79. With the passing of the years he came to have a greater respect for Christianity but because of his love for the deadly sins, especially pride, gluttony and lust he did not think he could rightly represent the Christian faith and so did not convert. By the nineteen fifties he was one of the best known British journalists in the world, a status that increased even more after the advent of TV. In the late sixties he went to Kolkata to meet Mother Theresa. Instead of being angry, Muggeridge’s heart melted as Mother Teresa forced him to wait for hours while she tended to the sick and the dying. Instead of having to fend off the intensity of this tiny nun’s love for the poorest of the poor, he embraced her indelibly by writing Something Beautiful for God. After his conversion Muggeridge remembered Mother Teresa of Kolkata, whose selfless work for India’s destitute he first told the world about, had a dramatic transforming effect on his life. Seeing the light of God illuminate the nun’s wizened face, seeing her complete trust in God, Muggeridge saw as never before “the pathetic condition of his worldly cynicism”. -

MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE THEGREEN STICK 'Johnson Needed Boswell, but Malcolm Muggeridge Needs No One Else' ANTONIA FRASER Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 1

CHRONICLES OF WASTED TIME VOL.1 MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE THEGREEN STICK 'Johnson needed Boswell, but Malcolm Muggeridge needs no one else' ANTONIA FRASER Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 1 The Green Stick Malcolm Muggeridge was born in 1903 and educated . at Selhurst Grammar School and Selwyn College, Cambridge. After lecturing at the Egyptian University in Cairo, he joined the editorial staff of the Man chester Guardian in 1930, and was Moscow Corre spondent for this paper from 1932-3. In the war of 1939-45 he served as an Intelligence. officer in North Africa, Mozambique, Italy and France, being seconded to M I6, the wartime version of the Secret Service. He ended up in Paris as Liaison Officer with the French Securite Militaire, and was awarded the Legion of Honour (Chevalier), the Croix de Guerre with Palm and the Medaille de la Reconnaissance Frani;:aise. His career as a journalist included a spell as Washington Correspondent of the Daily Telegraph from 1946-7, and Deputy Editorship from 1950-52. He was Editor of Punch from 1953-7 and Rectm of Edinburgh University from 1967-8. He has written numerous books since the early '30s, including Some thing Beautiful for God, Jesus Rediscovered, Tread Softly for you Tread on my Jokes, and The Thirties. He lives in Robertsbridge, Sussex. MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE Chronicles of Wasted Time Part I The Green Stick I used to believe that there was a green stick, buried on the edge of a ravine in the old Zakaz forest at Yasnaya Polyana, on which words were carved that would destroy all the evil in the hearts of men and bring them everything good. -

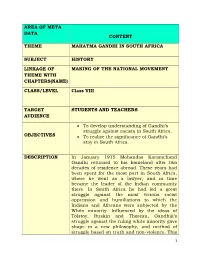

Area of Meta Data Content Theme Mahatma Gandhi In

AREA OF META DATA CONTENT THEME MAHATMA GANDHI IN SOUTH AFRICA SUBJECT HISTORY LINKAGE OF MAKING OF THE NATIONAL MOVEMENT THEME WITH CHAPTERS(NAME) CLASS/LEVEL Class VIII TARGET STUDENTS AND TEACHERS AUDIENCE To develop understanding of Gandhi’s struggle against racism in South Africa. OBJECTIVES To realize the significance of Gandhi’s stay in South Africa. DESCRIPTION In January 1915 Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi returned to his homeland after two decades of residence abroad. These years had been spent for the most part in South Africa, where he went as a lawyer, and in time became the leader of the Indian community there. In South Africa he had led a great struggle against the most vicious racist oppression and humiliations to which the Indians and Africans were subjected by the White minority. Influenced by the ideas of Tolstoy, Ruskin and Thoreau, Gandhiji’s struggle against the ruling white minority gave shape to a new philosophy, and method of struggle based on truth and non-violence. This 1 was Passive Resistance, or Satyagraha. It also meant mass actions through hartals, marches, mass violation of oppressive laws and mass courting of arrests. The challenges and trials that Gandhi underwent in Africa in the form of racist oppression was very significant. It gave birth to new ideas and philosophy, and method of struggle based on truth and non- violence. KEY WORDS Gandhi, Durban Court House, Tolstoy farm,, Pietermaritzburg Station, Satyagraha, Natal Indian Congress, Indian Ambulance Corps, Burning Cauldron, Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance, Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance, Hermann Kallenbach . CONTENT MILY ROY ANAND DEVELOPER SUBJECT MILY ROY ANAND COORDINATOR CIET INDU KUMAR COORDINATOR 2 Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s stay in South Africa from 1893 to 1915 was a significant chapter in the life of Gandhi.