Episode 3: Mother

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malcolm Muggeridge the Infernal Grove

e FONTANA MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE THE INFERNAL GROVE 'The wit sparkles on almost every page' BERNARD LEVIN Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 2 The Infernal Grove Malcolm Muggeridge was born in 1903 and educated at Selhurst Grammar School and Selwyn College, Cambridge. After lecturing at the Egyptian University in Cairo, he joined the editorial staff of the Man chester Guardian in 1930, and was Moscow Corre spondent for this paper from 1932-3. In the war of 1939-45 he served as an Intelligence officer in North Africa, Moz.ambique, Italy and France, being seconded to MI6, the wartime version of the Secret Service. He ended up in Paris as Liaison Officer with the French Securite Militaire, and was awarded the Legion of Hon0ur (Chevalier), the Croix de Guerre with Palm and the Medaille de la Reconnaissance Fran9aise. His career as a journalist included a spell' as Washington Correspondent of the Daily Telegraph from 1946-7, and Deputy Editorship from 1950-52. He was Editor of Punch from 1953-7 and Rector of Edinburgh University from 1967-8. He has written numerous books since the early '30s, including Some thing Beautiful for God, Jesus Rediscovered, Tread Softly for you Tread on my Jokes, and The Thirties. He lives in Robertsbridge, Sussex. Volume I of Chronicles of Wasted Time, The Green Stick, is abo available from Fontana, MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 2 The Infernal Grove Till I tum from Female Love, And root up the Infernal Grove, I shall never worthy be To step into Eternity Blake FONTA NA/Collins First published by William Collins Sons & Co. -

Streams of Civilization: Volume 2

Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press i Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 1 8/7/17 1:24 PM ii Streams of Civilization Volume Two Streams of Civilization, Volume Two Original Authors: Robert G. Clouse and Richard V. Pierard Original copyright © 1980 Mott Media Copyright to the first edition transferred to Christian Liberty Press in 1995 Streams of Civilization, Volume Two, Third Edition Copyright © 2017, 1995 Christian Liberty Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without written permission from the publisher. Brief quota- tions embodied in critical articles or reviews are permitted. Christian Liberty Press 502 West Euclid Avenue Arlington Heights, Illinois 60004-5402 www.christianlibertypress.com Copyright © 2017 Christian Liberty Press Revised and Updated: Garry J. Moes Editors: Eric D. Bristley, Lars R. Johnson, and Michael J. McHugh Reviewers: Dr. Marcus McArthur and Paul Kostelny Layout: Edward J. Shewan Editing: Edward J. Shewan and Eric L. Pfeiffelman Copyediting: Diane C. Olson Cover and Text Design: Bob Fine Graphics: Bob Fine, Edward J. Shewan, and Lars Johnson ISBN 978-1-629820-53-8 (print) 978-1-629820-56-9 (e-Book PDF) Printed in the United States of America Streams Two 3e TEXT.indb 2 8/7/17 1:24 PM iii Contents Foreword ................................................................................1 Introduction ...........................................................................9 Chapter 1 European Exploration and Its Motives -

Mother Teresa, the Angel of Calcutta

INDIA Mother Teresa, the angel of Calcutta ©Simone Bergamaschi Calcutta, India, Nirmala Shishu Bhavan it’s the house built by Mother Teresa and the Missionaries of Charity to welcome orphan kids and the ones with physical or mental problems. In the area there are a lot of families counting on this centre to give their children a better present. On September 4th, 2016 Pope Francis will proclaim saint a tiny nun from Albania, born in 1910 and passed away 87 years later: Mother Teresa. Just saying her name recalls immediately her minute figure, wrapped up in a white and blue sari, always with a smile on her wrinkled face. Having her name associated with the city of Calcutta (from 2001 officially known as Kolkata) is more difficult for many: it’s the place where Mother Teresa lived and worked most of her life, serving the poorest among the poorest surrounded by extreme indigence and its related violence, decay and enormous suffering. It was that immense poverty to push Mother Teresa to move to Calcutta right after completing her novitiate and her nurse education in the North Bengal. She never left Calcutta since then. Here she started to look after and cure the sick persons she was finding on the roads, founding later the order of the Missionaries of Charity and a huge number of homeless centres, hospitals and clinics dedicated to people affected by leprosy. In many occasions Mother Teresa found herself involved in controversies, but her tireless missionary activity gained more and more credibility as time went by. She also started to be supported from personalities like Lady Diana Spencer, and in 1979 she received the Nobel Peace Prize. -

Service-Learning in Japan

CH •X ANG DF E P w Click to buy NOW! w m o w c .d k. ocu•trac SERVICE LEARNING IN ASIA: Pedagogy and Networking 2007 Tunghai University Service Learning Conference 9th March Service•Learning in Japan Michio Matsuura President & Takaaki David Ito Dean of Student (~March 2007) Director, International Centre (April 2007~) St. Andrew's University, Momoyama Gakuin CH •X ANG DF E P w Click to buy NOW! w m o w c .d k. ocu•trac Momoyama Gakuin University •Mission:"Fostering Citizens of the World" •An Anglican University in Japan •Social Science Orientation: –No Science Faculty •Active in International Partnership for Service• Learning and Leadership •A Core Member Institution Promoting International Experiential Education in Japanese Higher Education CH •X ANG DF E P w Click to buy NOW! w m o w c .d k. ocu•trac Japanese University Education (Historical Perspective) • 19/20 Century: Education for Bureaucracy – Training for Powerful Administrator – Nation(=People) Serves, State(=Bureaucrat) Rules • Post WW2: Education for Growth – Power Orientation; Personal Achievements • Late 20 Century: Professionalism – "Service" as Practicum for Professional Qualifications • 20/21 Century: Citizenship Education – Community Service – International Service Learning CH •X ANG DF E P w Click to buy NOW! w m o w c .d k. ocu•trac Curriculum of Service•Learning (1: Core / Professional) Core Professional Education Education CH •X ANG DF E P w Click to buy NOW! w m o w c .d k. ocu•trac Curriculum of Service•Learning (2: Value Edu / Practical Edu) Practical Education Value Education CH •X ANG DF E P w Click to buy NOW! w m o w c .d k. -

Come and See

Members of the Mother Teresa tried to convince Linda Corporation and the Schaefer to become a nun in 1995, but instead, the Come 2016 Board Of Directors great humanitarian gave Schaefer rare permission to of Catholic Charities of document the work in Calcutta during her six- month Harrisburg: stay in the city where Mother Teresa founded the and See... Bishop Ronald Gainer, D.D., Missionaries of Charity. A Community J.C.L As a result of that auspicious journey, Schaefer Gathering to Support Mark A. Totaro, PH.D. has had two books published based on personal Linda Schaefer Catholic Charities’ Very Reverend David L. journey with Mother Teresa, and a second book that includes interviews Danneker, PH.D., V.G. with priests and one of her sisters who worked with Blessed Teresa of Homes For Healing Reverend Daniel C. Mitzel Calcutta for over two decades. She is presently writing a third book which will include numerous other interviews from over 21 years of meeting A Benefit Dinner Mr. Brian P. Downey, Esq people who had known or worked with the humanitarian. Schaefer has Mr. Joseph F. Schatt spoken for over 1,000 audiences since 1998. Her first Catholic Charities Featuring Ms. Zenoria McMorris Owens in Harrisburg, PA in 2006 led to additional Catholic Charities fund raising Guest Speaker Mr. Richard Berrones speaking engagements including: Spokane, WA, Dallas, TX and Reno, NV. Linda Schaefer Mrs. Maria DiSanto In early December of 2015, Schaefer once again visited the motherhouse where Mother Teresa is now buried. On her first day in Mr. David S. -

“Creating Many Ripples” Homily for 23 Sunday of Ordinary Time

1 “Creating many Ripples” Homily for 23rd Sunday of Ordinary Time September 4th 2016 Wisdom of Solomon 9:13–18b Psalm 90:3–6, 12–17 Philemon 9–10, 12–17 Gospel Luke 14:25–33 In December 1982 Malcolm Muggeridge became a Roman Catholic. What made this event so significant was the fact that for much of his life, he was either an atheist, in his younger years, or an agnostic, during midlife. He was born in 1903 and was received into the Church at age 79. With the passing of the years he came to have a greater respect for Christianity but because of his love for the deadly sins, especially pride, gluttony and lust he did not think he could rightly represent the Christian faith and so did not convert. By the nineteen fifties he was one of the best known British journalists in the world, a status that increased even more after the advent of TV. In the late sixties he went to Kolkata to meet Mother Theresa. Instead of being angry, Muggeridge’s heart melted as Mother Teresa forced him to wait for hours while she tended to the sick and the dying. Instead of having to fend off the intensity of this tiny nun’s love for the poorest of the poor, he embraced her indelibly by writing Something Beautiful for God. After his conversion Muggeridge remembered Mother Teresa of Kolkata, whose selfless work for India’s destitute he first told the world about, had a dramatic transforming effect on his life. Seeing the light of God illuminate the nun’s wizened face, seeing her complete trust in God, Muggeridge saw as never before “the pathetic condition of his worldly cynicism”. -

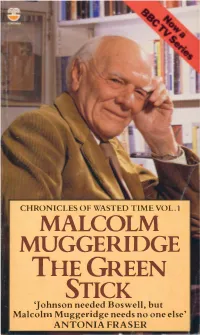

MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE THEGREEN STICK 'Johnson Needed Boswell, but Malcolm Muggeridge Needs No One Else' ANTONIA FRASER Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 1

CHRONICLES OF WASTED TIME VOL.1 MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE THEGREEN STICK 'Johnson needed Boswell, but Malcolm Muggeridge needs no one else' ANTONIA FRASER Chronicles of Wasted Time Part 1 The Green Stick Malcolm Muggeridge was born in 1903 and educated . at Selhurst Grammar School and Selwyn College, Cambridge. After lecturing at the Egyptian University in Cairo, he joined the editorial staff of the Man chester Guardian in 1930, and was Moscow Corre spondent for this paper from 1932-3. In the war of 1939-45 he served as an Intelligence. officer in North Africa, Mozambique, Italy and France, being seconded to M I6, the wartime version of the Secret Service. He ended up in Paris as Liaison Officer with the French Securite Militaire, and was awarded the Legion of Honour (Chevalier), the Croix de Guerre with Palm and the Medaille de la Reconnaissance Frani;:aise. His career as a journalist included a spell as Washington Correspondent of the Daily Telegraph from 1946-7, and Deputy Editorship from 1950-52. He was Editor of Punch from 1953-7 and Rectm of Edinburgh University from 1967-8. He has written numerous books since the early '30s, including Some thing Beautiful for God, Jesus Rediscovered, Tread Softly for you Tread on my Jokes, and The Thirties. He lives in Robertsbridge, Sussex. MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE Chronicles of Wasted Time Part I The Green Stick I used to believe that there was a green stick, buried on the edge of a ravine in the old Zakaz forest at Yasnaya Polyana, on which words were carved that would destroy all the evil in the hearts of men and bring them everything good. -

The Canonization of Mother Teresa and Its Relevance

|| Volume 2 || Issue 12 || DECEMBER 2017 || ISO 3297:2007 Certified ISSN (Online) 2456-3293 (Multidisciplinary Journal) THE CANONIZATION OF MOTHER TERESA AND ITS RELEVANCE Mousumi Biswas Assistant Professor, Department of English Sri Aurobindo College University of Delhi ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ABSTRACT: mother teresa has been one of the most well-known personalities in India and also across the world. Amongst her numerous accolades, the most note-worthy are the noble prize, the beatification and the canonization. in spite of such recognitions, she has also been criticized for her stand against divorce, abortion, remarriage or her perception about transgenders. it is necessary to see not the individual making such statements or holding such views, but to understand that she is speaking on behalf of the church and has no option to defy it. this paper also goes on to explain the necessity of miracles as a prerequisite for canonization and shows how it is relevant for religion per se. Keywords: Mother Teresa, canonization, beatification, miracle, Catholic, abortion. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- INTRODUCTION kinds of ailing people, even those suffering from diseases like AIDS and leprosy (Greene, 2004).Inspite of that, she has had Mother Teresa has been one of the most well-known her fair share of criticisms as well and in the event of her personalities in India and also across the world. Amongst her canonization last year in 2016, it perhaps becomes more numerous accolades, the most note-worthy are the noble relevant to dig them up in the context of this article. prize, the beatification and the canonization. In spite of such recognitions, she has also been criticized for her stand against Notable amongst her critics have been Christopher divorce, abortion, remarriage or her perception about Hitchens, the American- British journalist, who attacked her transgenders. -

Ethical Record

The ISSN 0014- 1690 Ethical Record Vol. 96 No. 9 OCTOBER 1991 CONTENTS Page Saint Mugg 3 Relation between Brain vc Consciousness 7 Book Review 12 Letters 14 London Student Skeptics 15 Forthcoming Events 16 Editorial This issue of The Ethical Record is unusually Perhaps the strongest reason for retaining short due to an absence of suitable material. the present title is that of tradition. But this is Due to the economics and technology of no reason at all. It is simply to say that things printing the journal must be in increments of have always been thus, so they must remain 8 pages. so. Even if it were the case that a particular usage had always been so this would not of Three years ago Nicolas Walter suggested itself be a good enough reason for retaining it. that it was time to consider changing the But such appeals to tradition usually arbitrarily name of the South Place Ethical Society ('A stop in historical reference at the moment Century of the Ethical Movement', ER, when that particular usage itself became September '88). This suggestion seemed to current. This is so in the case of the present elicit little response. I will repeat this proposal name for the Society. It was not always called and invite readers to reply: by its present name and need not continue to The premises of the Society are no longer be so. -at South Place, so 'South Place' is no longer an accurate qualification of 'Ethical Society'. But then again: surely the 'it' itself has changed. -

A Day in Kolkata"

"A Day in Kolkata" Realizado por : Cityseeker 14 Ubicaciones indicadas Mother House "A Glimpse into the Finest Life" 54 Bose Road is one of the most famous addresses in Kolkata and an important stopover for every tourist visiting the city. The building aptly called Mother House is the headquarters of the Missionaries of Charity, Mother Teresa's vision to spread hope and love to the despair. Even today, Mother Teresa’s sisters of charity, clad in their trademark blue- by Hiroki Ogawa bordered saris, continue to carry forward her legacy. Visitors can pay their respects at the Mother's tomb and visit the museum displaying objects from her routine life – sandals and a worn-out bowl that stand as true reflections of her simplicity. Invoking peace and a range of different emotions, this place allows you to catch a glimpse into the life of one of the finest human beings to have ever lived. +91 33 245 2277 www.motherteresa.org/ 54/A A.J.C. Bose Road, Missionaries of Charity, Calcuta Raj Bhavan "Royal Residence" During the colonial rule, the Britishers erected magnificent structures and palatial residences, that often replicated buildings and government offices back in England. Raj Bhavan is one of such splendid heritage landmarks in the city of Kolkata. Spread across 27 acres, the wrought iron gates and imposing lions atop, create a majestic allure to the whole place and draw a clear line of distinction between the powerful rulers and the powerless common man. It continued to be the official residence of Governor- Generals and Viceroy until Kolkata ceased to be the capital of India and Delhi came into prominence. -

By Christopher Hitchens

1 god is not great by Christopher Hitchens Contents One - Putting It Mildly 03 Two - Religion Kills 07 Three - A Short Digression on the Pig; or, Why Heaven Hates Ham 15 Four - A Note on Health, to Which Religion Can Be Hazardous 17 Five - The Metaphysical Claims of Religion Are False 24 Six - Arguments from Design 27 Seven - Revelation: The Nightmare of the "Old" Testament 35 Eight - The "New" Testament Exceeds the Evil of the "Old" One 39 Nine - The Koran Is Borrowed from Both Jewish and Christian Myths 44 Ten - The Tawdriness of the Miraculous and the Decline of Hell 49 Eleven - "The Lowly Stamp of Their Origin": Religion's Corrupt Beginnings 54 Twelve - A Coda: How Religions End 58 Thirteen - Does Religion Make People Behave Better? 60 Fourteen - There Is No "Eastern" Solution 67 Fifteen - Religion as an Original Sin 71 Sixteen - Is Religion Child Abuse? 75 Seventeen - An Objection Anticipated: The Last-Ditch "Case" Against Secularism 79 Eighteen - A Finer Tradition: The Resistance of the Rational 87 Nineteen - In Conclusion: The Need for a New Enlightenment 95 Acknowledgments 98 References 99 2 Oh, wearisome condition of humanity, Born under one law, to another bound; Vainly begot, and yet forbidden vanity, Created sick, commanded to be sound. —FULKE GREVILLE, Mustapha And do you think that unto such as you A maggot-minded, starved, fanatic crew God gave a secret, and denied it me? Well, well—what matters it? Believe that, too! —THE RUBAIYAT OF OMAR KHAYYAM (RICHARD LE GALLIENNE TRANSLATION) Peacefully they will die, peacefully they will expire in your name, and beyond the grave they will find only death. -

English Or Anglo-Indian?: Kipling and the Shift in the Representation of the Colonizer in the Discourse of the British Raj

English or Anglo-Indian?: Kipling and the Shift in the Representation of the Colonizer in the Discourse of the British Raj Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Catherine Elizabeth Hart, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Clare Simmons, Advisor Jill Galvan Amanpal Garcha Pranav Jani Copyright by Catherine Elizabeth Hart 2012 Abstract Using Rudyard Kipling as the focal point, my dissertation examines nineteenth- century discourse on English identity and imperialism through literature of the British Raj written in the 1840s through the 1930s. In my analysis of this literature, I identify a shift in the representation of the colonizer between English and Anglo-Indian in four distinct historical moments: pre-Rebellion (1857), post-Rebellion, the fin de siècle, and post- World War I. While the term Anglo-Indian can be used as a simple means of categorization—the Anglo-Indian is the English colonizer who lives in and conducts imperial work in India as opposed to one of the other British colonies—it also designates a distinct cultural identity and identifies the extent to which the colonizer has been affected by India and imperialism. As such, the terms Anglo-Indian and English, rather than being interchangeable, remain consistently antithetical in the literature with one obvious exception: the Kipling canon. In fact, it is only within the Kipling canon that the terms are largely synonymous; here, the Anglo-Indian colonizer is represented not only as a positive figure but also as a new and improved breed of Englishman.