Post-Soviet, Post-Mining and Post-Agriculture Landscape Wind Parks in Estonia: Displaying Regional Pride and Being Possible Tourist Attraction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imastu Est 19-18

PROJECT CODE IMASTU EST 19-18 Project details Code: EST 19-18 Date: 2018-07-10 / 2018-08-01 Total places: 1 Age: 19 - 30 Name: IMASTU Type of work: Social project (SOCI) Country: ESTONIA Location: TAPA Address: TAPA Email: Phone Number: Web: Fee: 0.0 EUR Languages: English, English Description Partner: Give your hand and heart to disable young people ProjectImastu Residential School is an institution for mentally handicapped children and youngsters. It caters for over 100 kids and young adults aged 5 to 35 with serious mental and genetic diseases. Most of them are orphans. Youngsters are divided in to 5 family groups where they live under supervision of staff. Children attend a special school arranged for them in Imastu. Since 1994 Imastu has been hosting international workcamps in summer and since 1999 - long-term volunteers to assist staff with daily work, bringing new ideas and approaches to the daily routine. Volunteers are wanted to support staff and assist work with kids, especially in summer when it is possible to offer a lot more diverse outdoor activities for kids. See more about Imastu Residential School on http://www.hoolekandeteenused.ee/imastu/pages/galerii.php Workcamp in Imastu is the eldest in EstYES i we have been hosting volunteers there for 25 years Work: Looking after the youngsters, helping staff in teaching basic skills, playing with them, arranging their outings, assisting in all other required activities. Each volunteer will work in the own family group. Volunteers will work under supervision and with assistance of local staff about 35 hours a week, 2 days a week are free. -

Kodade Tourist Farm Est 36-19

PROJECT CODE KODADE TOURIST FARM EST 36-19 Project details Code: EST 36-19 Date: 2019-08-19 / 2019-08-30 Total places: 2 Age: 18 - 30 Name: KODADE TOURIST FARM Type of work: Environmental (ENVI) Country: ESTONIA Province: SIN PROVINCIA Location: KOERA KULA Address: KOERA KULA Email: Phone Number: Web: Emergency: Fee: 50.0 EUR Languages: English, English Fax: GPS location GPS: lat: 58.697399, lng: 23.551599799999 Click to open in Google Maps Description Partner: Kodade cottage and Matsalu Creative Space are social enterprise initiatives which aim to sustain cultural heritage and to provide a rich variety of nature tourism services and active tourism services in the setting of unique wild nature. We also aim to provide work opportunities for people living in rural area.We have created a unique environment for creative camps, study camps and various types of events. We value sustainable living and align our activities with Matsalu National Park value system. Matsalu National Park has been created to protect migratory birds and is one of the most important protection areas of nesting and stop-over of coastal birds in Europe. In addition to bird protection Matsalu protects specific semi-natural habitats (coastal meadows and broods; woody meadows; reed bed and small islands) as well as the cultural heritage of the Vainameri sea https://kaitsealad.ee/eng/matsalu-national-park Work: We offer a wide range of activities to our volunteers i mostly in the field of maintenance and development of the visitor site and the territory but also related to nature conservation in the surrounding area. -

A Shift from Cult to Joke? *

Folklore. Electronic Journal of Folklore Folklore 7 1998 CLOTHED STRAW PUPPETS IN ESTONIAN FOLK CALENDAR TRADITION: A SHIFT FROM CULT TO JOKE? * Ergo-Hart Västrik In our country at the time of the end of the rule of the Swedish kings there was in some places the pagan custom, known also elsewhere in the world. On Shrove Tuesday people made a puppet figure which they called metsik [the Wild One]. One year they put on it a man's hat and an old coat, the next year they put on it a coif and a woman's dress. They hoisted this figure up on a long pole and, dancing and singing, carried it across the border of their village, borough or parish and tied it to the top of a tree in the woods. This was to mean that all mishaps and bad luck were over and that grain and flax were to give good yield in this year. In Germany, where a similar thing was done in the past, people said that they were taking away winter or death. (Eesti-ma rahva... 1838, Laakmann, Anderson 1934: 14, Laugaste 1963: 138-139). The present paper deals with the custom of metsiku tegemine [making the Wild One, Estonian mets 'forest'],1 i.e. a tradition of making a straw puppet, dressed as a man or a woman, which was carried out of the community territory on one of the yearly winter festivals of the folk calendar. The cus- tom, known in several West Estonian parishes, was relatively well-documented already at the turn of the 17th century when it was described as a pagan rite of peasants. -

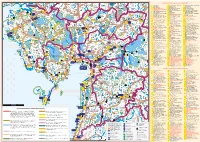

Haapsaluand - O N LÄÄNE COUNTY M O I M T O a C D C a G N I R E T a C S M U E S U M S E I T I V I T C a E D a R T S P a ENGLISH M HAAPSALU and LÄÄNE COUNTY 2 SIGNS

HA LÄÄNE COUNTY APSAL ENGLISH U and ACCOMMO- MAPS TRADE ACTIVITIES MUSEUMS INFO CATERING DATION ENG HAAPSALU and LÄÄNE COUNTY 2 SIGNS 155 Lodging WIFI WIFI WC 160 Catering WC for disabled Bar Sports activities WC Water Closet VISA Credit cards accepted SAUNA Sauna Skiing Shower Billiards Telephone 2 Rooms for disabled TV TV Campfire Silence Boat 50 m Bus stop Fireplace 300 m Beach 40 Caravans P Parking Tent places 7 Bicycles Tennis Gym Yacht harbour Golf Hot drink Hunting Luggage room Domestic ENG animals FIN languages RUS Fishing SWE GER G N HAAPSALU and LÄÄNE COUNTY 3 CONTENTS E O DEAR GUEST, CONTENTS F N I Welcome to the most romantic and mythical spot in Signs 2 Estonia - Haapsalu and Läänemaa. Contents 3 Travel Agencies 4 INFO It is easy to fall in love with Haapsalu: once here, 5 Transport 5 the winding streets ending up at the sea, the old Taxi 5 town with houses adorned with wooden lace and Ports 6 the mysterious White Lady appearing in a chapel Petrol-stations 6 window on moonlit nights will keep the visitor Internet 7 spellbound. WIFI 8 ACCOMMODATION The pebble beaches, squealing seabirds, grassy Rehabilitation centres 9 meadows and peaceful groves will appeal to Hotels in Haapsalu 10 Guesthouses & hostels visitors fond of nature and serenity. Matsalu's in Haapsalu 11-12 abundant bird sanctuary draws visitors from all Accommodation in Lääne County: over the world - it is Europe's biggest and most Ridala Parish 13 diverse nesting area for migratory birds. Taebla Parish 14 Nõva Parish 14 History lovers should make time to look into Lihula Parish 14 medieval churches and castle ruins so typical to Oru Parish 14 Läänemaa. -

Alliksaare Farm Iv Est 24-19

PROJECT CODE ALLIKSAARE FARM IV EST 24-19 Project details Code: EST 24-19 Date: 2019-07-29 / 2019-08-23 Total places: 2 Age: 18 - 30 Name: ALLIKSAARE FARM IV Type of work: Environmental (ENVI) Country: ESTONIA Location: NURSTE KULA Address: NURSTE KULA Email: Phone Number: Web: Fee: 50.0 EUR Languages: English, English GPS location GPS: lat: 58.786429299999, lng: 22.4928978 Click to open in Google Maps Description Partner: Hiiumaa according to the Nordic sagas emerged from the Baltic Sea as a small islet more than 10 000 years ago. The island of Hiiumaa was first mentioned in historical documents as a deserted island called Dageida in 1228. The first inhabitants settled down at the end of the 13th century. Nowadays Hiiumaa is the second biggest island of Estonia with the area of 965 sq. km and the population around 10 000. It has many historical and nature sights, and there are kind people known for their hospitality and good sense of humor. The island is referred as a remote area of Europe, and EstYES feels particularly proud developing international voluntary projects for almost twenty years there. Besides, for years EstYES has been cooperating with eco-farms all over Estonia for solidarity, respect and practical support to local people who work in agricultural sector keeping traditional life style and developing new eco- farming despite of all difficulties. Alliksaare Farm on Hiiumaa Island is one of such projects. This is an organic farm promoting sustainable lifestyle, and this camp is proposed for volunteers who appreciate and share its values, want to learn more about it and to help hard working people. -

Pärnumaa-Kaart-EST-FIN.Pdf

gi jõ E Kirna E 5 E äru Kiideva Raana jõgi Kilgi K jõgi jõgi VAATAMISVÄÄRSUSED PÄRNU MAAKONNAS Puise km T 4 a ra Kabeli 2 m Järvakandi ti Kastja Päärdu l Velisemõisa Nurtu Rõud s l k e jõgi i i Kõrbja n R Vana-Vigala Velise- Inda 9 Mäda Illaste raba n Nõlva 2 Nõlvassoo Saarepõllu Võeva Nurtu-Nõlva Soo-otsa Karjaküla 1 Auto24ring 44 Kirsi Vanasõidukite muuseum 91 Soomaa rahvuspark, looduskeskus 8 Nõlva a Suurrahu Läti l 1 Rõude Laiküla E Tõrasoo p k 2 Villa Andropoff 45 Laelatu puisniit ja matkarajad a Eidapere m lka Kenni R Selja Kasa m Allikotsa Aravere Mäliste k 3 White Beach Golf 46 Hanila muuseum 92 Tipu Looduskool 57 Oese Kohtru 0 Matsalu laht 56 Paljasmaa 1 ri i Matsalu rahvuspark Araste jõgi Saug Kullimaa r 4 Valgeranna Seikluspark 47 Hanila Pauluse kirik (13. saj) 93 Kõpu Külastuskeskus jõgi Eidapere ü Kasari jõgi jõgi Vängla õgi T 52 Seli Vigala- Nurtu j a ra Valgeranna liivarand, promenaad Kõmsi tarandkalmed Piesta Kuusikaru talu Kurevere u 5 48 94 Kelu Rannu Vigala jõgi Keemu Keskküla jõgi Tõnumaa Vanamõisa Palase Nurme Ojaäärse Rahkama Penijõgi Kloostri Manni Mukri Pärn ja vaatlustorn 49 Karuse Püha Margareeta kirik 95 Vändra Martini luteri kirik (1787) 59 Kojastu Vaguja Reonda Vänd 2 Uluste Jõeääre Rääski Kõnn Ð 6 Audru mõisakompleks (18. saj) ja (13. saj) 96 Vändra Peeter-Pauli apostliku- ü 58 60 u jõgi 5 Saastna 51 Matsalu Kasari Kõnnu Mukri mka Liustemäe 29 Pagasi Mõisimaa Rumba Konnapere Audru muuseum 50 Ranna Rantšo õigeusu kirik (1868) jõgi Penijõe Ojapere Rukkiküla Kaisma raba 7 Ellamaa Kesu 2 u DC Audru Püha Risti -

Tartu Ülikool Filosoofiateaduskond Ajaloo Ja Arheoloogia Instituut

TARTU ÜLIKOOL FILOSOOFIATEADUSKOND AJALOO JA ARHEOLOOGIA INSTITUUT Allar Haav LÄÄNE- JA HIIUMAA 13.–18. SAJANDI KÜLAKALMISTUD Bakalaureusetöö Juhendaja: vanemteadur Heiki Valk Tartu 2011 Sisukord Sissejuhatus ................................................................................................................ 4 1. Külakalmistute paiknemine ............................................................................... 7 1.1 Külakalmistud üldises asustuspildis .............................................................. 9 1.1.1 Asustuspilt ja külakalmistud kihelkonniti ............................................. 9 1.1.1.1 Audru kihelkond ............................................................................ 11 1.1.1.2 Emmaste kihelkond ....................................................................... 12 1.1.1.3 Hanila kihelkond ........................................................................... 13 1.1.1.4 Käina kihelkond ............................................................................ 14 1.1.1.5 Karuse kihelkond ........................................................................... 15 1.1.1.6 Kirbla kihelkond ............................................................................ 16 1.1.1.7 Kullamaa kihelkond ...................................................................... 17 1.1.1.8 Lihula kihelkond............................................................................ 18 1.1.1.9 Lääne-Nigula kihelkond ................................................................ 19 -

Archaeological Research in Estonia 1865 – 2005

EA E A ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN ESTONIA 1865 – 2005 IN ESTONIA RESEARCH ARCHAEOLOGICAL A R E – Archaeological Research in Estonia 1865 – 2005 ea.indb 1 27.02.2006 23:17:25 ea.indb 2 27.02.2006 23:17:43 Estonian Archaeology 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN ESTONIA 1865 – 2005 Tartu University Press Humaniora: archaeologica ea.indb 3 27.02.2006 23:17:43 Official publication of the Chair of Archaeology of the University of Tartu Estonian Archaeology Editor-in-Chief: Valter Lang Editorial Board: Anders Andrén University of Stockholm, Sweden Bernhard Hänsel Freie Universität Berlin, Germany Volli Kalm University of Tartu, Estonia Aivar Kriiska University of Tartu, Estonia Mika Lavento University of Helsinki, Finland Heidi Luik Tallinn University, Estonia Lembi Lõugas Tallinn University, Estonia Yevgeni Nosov University of St. Petersburg Jüri Peets Tallinn University, Estonia Klavs Randsborg University of Copenhagen, Denmark Jussi-Pekka Taavitsainen University of Turku, Finland Andres Tvauri University of Tartu, Estonia Heiki Valk University of Tartu, Estonia Andrejs Vasks University of Latvia, Latvia Vladas Žulkus University of Klaipeda, Lithuania Estonian Archaeology, 1 Archaeological Research in Estonia 1865–2005 Editors: Valter Lang and Margot Laneman English editors: Alexander Harding, Are Tsirk and Ene Inno Lay-out of maps: Marge Konsa and Jaana Ratas Lay-out: Meelis Friedenthal © University of Tartu and the authors, 2006 ISSN 1736-3810 ISBN-10 9949-11-233-8 ISBN-13 978-9949-11-233-3 Tartu University Press www.tyk.ee Order no. 159 ea.indb 4 27.02.2006 23:17:43 Contents Contributors 7 Editorial 9 Part I. General Trends in the Development of Archaeology in Estonia Th e History of Archaeological Research (up to the late 1980s). -

Haldusüksused Ja Nende Lühendid Administrative Units of Estonia and Their Abbreviations (1866–2017)

Eesti Keele Instituut Institute of the Estonian Language KNAB: Kohanimeandmebaas / Place Names Database 30.10.2017 (03.05.1995) EESTI HALDUSÜKSUSED JA NENDE LÜHENDID ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS OF ESTONIA AND THEIR ABBREVIATIONS (1866–2017) Loetelus on Eesti haldusüksused ajavahemikus 1866–2017, seejuures 1950–1970 on arvesse võetud ainult linnad ja alevid. Valdade (1970–1989~91 ka külanõukogude) nimed on antud ilma liigisõnata. Praegused haldusüksuste nimed on poolpaksus kirjas , kihelkonnanimed on *tärniga. Teises tulbas on osutatud, millisesse kihelkonda kuulus omaaegne mõisavald ning millises maakonnas oli/on üksus 1922., 1939. ja 2017. a. Kolmandas tulbas on kohanimeandmebaasis kasutatav lühend. Märkuste lahtris on toodud viited haldusüksuse loomise, ümbernimetamise või likvideerimise kohta (allikaks Uuet 2002, Ajalooarhiivi andmebaas ja KNABi jaoks kogutud andmed). Mõne enne 1890ndaid olnud valla liitmise aeg ei ole teada, sel juhul on märkuses vaid XIX saj (vahel on tegu olnud pooliseseisva vallaga). Valdade tinglikuks algusajaks on 1866, kuid enamik valdu oli teises staatuses olemas juba varem. Tingmärgid: > liidetud millegagi, < lahutatud millestki, ^ ümber nimetatud v endise nimega. Lühend krkv = kirikuvald. Üksuste omavahelisi piirimuutusi ei kajastata. Põhitabeli järel on lühendite, samuti omaaegsete saksa- ja venekeelsete nimede register. Haldusüksused, mille lühendeid pole antud, kirjutatakse kohanimeandmebaasis täielikult välja, lisades sünonüüminumbri vastavalt tabelile, kui see on antud (nt Atla2, Jõgisoo1 ). The list contains names of administrative units of Estonia from the period 1866–2017, from 1950 through 1970 only urban municipalities are included. The names of rural municipalities are written without a generic term ( "vald" ). The names of current administrative units are in bold , the names of ecclesiastical parishes are marked with an *asterisk. The second column refers to the parish the unit belonged to before 1917 and the counties that the unit belonged to in 1922, 1939 and 2017. -

Kasutatud Allikad

809 KASUTATUD ALLIKAD Aabrams 2013 = Aabrams, Vahur. Vinne õigõusu ristinimeq ja näide seto vastõq. — Raasakõisi Setomaalt. Hurda Jakobi silmi läbi aastagil 1903 ja 1886. Hagu, P. & Aabrams, V. (koost.) Seto Kirävara 6. Seto Instituut, Eesti Kir- jandusmuuseum. [Värska–Tartu] 2013, lk 231–256. Aben 1966 = Aben, Karl. Läti-eesti sõnaraamat. Valgus, Tallinn 1966. Academic = Словари и энциклопедии на Академике. Академик 2000–2015. http://dic.academic.ru/. Ageeva 1989 = Агеева, Р. А. Гидронимия Русского Северо-Запада как источник культурно-исторической информации. Наука, Москва 1989. Ageeva 2004 = Агеева, Р. А. Гидронимия Русского Северо-Запада как источник культурно-исторической информации. Издание второе, исправленное. Едиториал УРСС, Москва 2004. Ahven 1966 = Ahven, Heino. Härgla või Härküla? — Ühistöö 04.08.1966. Aikio 2000 = Aikio, Ante. Suomen kauka. — Virittäjä 2000, lk 612–613. Aitsam 2006 = Aitsam, Mihkel. Vigala kihelkonna ajalugu. [Väljaandja Vigala Vallavalitsus ja Volikogu.] s. l. 2006. Alasti maailm 2002 = Alasti maailm: Kolga lahe saared. Toimetajad Tiina Peil, Urve Ratas, Eva Nilson. Tallinna Raamatutrükikoda 2002. Alekseeva 2007 = Алексеева, О. А. Рыболовецкий промысел в Псковском крае в XVIII в. — Вестник Псковского государственного педагогического университета. Серия: Социально-гуманитарные и психолого-педаго- гические науки, № 1. Псков 2007, 42–53. http://histfishing.ru/component/content/article/1-fishfauna/315- alekseeva-oa-ryboloveczkij-promysel-v-pskovskom-krae-v-xviii-v (Vaadatud 02.11.2015) Almquist 1917–1922 = Den civila lokalförvaltningen i Sverige 1523–1630. Med särskild hänsyn till den kamerala indelningen av Joh. Ax. Almquist. Tredje delen. Tabeller och bilagor. Stockholm 1917–1922. Aluve 1993 = Aluve, Kalvi. Eesti keskaegsed linnused. Valgus, Tallinn 1993. Alvre 1963 = Alvre, Paul. Kuidas on tekkinud vere-lõpulised kohanimed. -

Matsalu Lahe Matsalu Mägari, Ridala Vald Varbla Muuseum

19. Oidremaa mõis 3. Kuuse talu jaanalinnufarm Kajakimatkad / Uue-Varbla mõis / Uue-Varbla manor Keemu vaatetorn / Tel +372 446 2316 Tel +372 472 0733, +372 5554 0118 varaklassitsistlikus stiilis puitmõis on Keemu observation tower [email protected] [email protected], www.jaanalinnud.ee Kayaking tours pärit aastast 1798, mõisa saalis asub 6-meetrine torn asub Matsalu lahe Matsalu www.oidremaa.ee Mägari, Ridala vald Varbla Muuseum. lõunarannikul Keemu sadama juures. Mõhk ja Tölpa OÜ Sellest tornist on Matsalu lahe keskosa Oidremaa, Koonga vald 4. Ridala tall Varbla kirik / Varbla church piirkonna teejuhis tel +372 59012355 laiud ja lahe madalaveeline sisemine 20. Varbla puhkeküla Ranna motell Tel +372 5676 0542, [email protected] esmakordselt mainitud 1638. a., 1803. [email protected] osa koos roostikega ning rannaniidud. Infopunkt / Tel +372 506 1879 ridalatall.weebly.com a. ehitati uus puukirik, mis aga 1860. a. [email protected] Vilkla, Ridala vald sisse langes, kuid samal aastal ehitati Kiideva vaatetorn / Information centre www.varblapuhkekyla.ee Vaatamisväärsused / uus kirik. Kiideva observation tower 5. Suure-Lähtru mõis Torn asub sadamahoone katusel, kust Matsalu Looduskeskus Rannaküla, Varbla vald Tel +372 529 7505, +372 528 2588 Sightseeings (RMK teabepunkt) / Koonga vald / parish avaneb vaade Matsalu lahele teisel Matsalu Nature Centre 21. Surfhunt & Hundimaja [email protected] Matsalu rahvuspark / pool roostikke. Kalli-Nedrema puisniit / Tel +372 472 4236 Tel +372 565 5606 www.hot.ee/suurelahtru Matsalu National Park [email protected], www.surfhunt.ee Suure-Lähtru, Martna vald Rahvuspargi keskus asub Penijõe Kalli-Nedrema wooded meadow Kloostri vaatetorn / [email protected] Euroopas suuruselt teine taastatud Kloostri observation tower Rannaküla, Varbla vald 6. -

Kodade Tourist Farm Est 36-19

PROJECT CODE KODADE TOURIST FARM EST 36-19 Project details Code: EST 36-19 Date: 2019-08-19 / 2019-08-30 Total places: 2 Age: 18 - 30 Name: KODADE TOURIST FARM Type of work: Environmental (ENVI) Country: ESTONIA Province: SIN PROVINCIA Location: KOERA KULA Address: KOERA KULA Email: Phone Number: Web: Emergency: Fee: 50.0 EUR Languages: English, English Fax: GPS location GPS: lat: 58.697399, lng: 23.551599799999 Click to open in Google Maps Description Partner: Kodade cottage and Matsalu Creative Space are social enterprise initiatives which aim to sustain cultural heritage and to provide a rich variety of nature tourism services and active tourism services in the setting of unique wild nature. We also aim to provide work opportunities for people living in rural area.We have created a unique environment for creative camps, study camps and various types of events. We value sustainable living and align our activities with Matsalu National Park value system. Matsalu National Park has been created to protect migratory birds and is one of the most important protection areas of nesting and stop-over of coastal birds in Europe. In addition to bird protection Matsalu protects specific semi-natural habitats (coastal meadows and broods; woody meadows; reed bed and small islands) as well as the cultural heritage of the Vainameri sea https://kaitsealad.ee/eng/matsalu-national-park Work: We offer a wide range of activities to our volunteers i mostly in the field of maintenance and development of the visitor site and the territory but also related to nature conservation in the surrounding area.