WORKBOOK in CHEMISTRY (I) (Inorganic & Bioinorganic)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reductions and Reducing Agents

REDUCTIONS AND REDUCING AGENTS 1 Reductions and Reducing Agents • Basic definition of reduction: Addition of hydrogen or removal of oxygen • Addition of electrons 9:45 AM 2 Reducible Functional Groups 9:45 AM 3 Categories of Common Reducing Agents 9:45 AM 4 Relative Reactivity of Nucleophiles at the Reducible Functional Groups In the absence of any secondary interactions, the carbonyl compounds exhibit the following order of reactivity at the carbonyl This order may however be reversed in the presence of unique secondary interactions inherent in the molecule; interactions that may 9:45 AM be activated by some property of the reacting partner 5 Common Reducing Agents (Borohydrides) Reduction of Amides to Amines 9:45 AM 6 Common Reducing Agents (Borohydrides) Reduction of Carboxylic Acids to Primary Alcohols O 3 R CO2H + BH3 R O B + 3 H 3 2 Acyloxyborane 9:45 AM 7 Common Reducing Agents (Sodium Borohydride) The reductions with NaBH4 are commonly carried out in EtOH (Serving as a protic solvent) Note that nucleophilic attack occurs from the least hindered face of the 8 carbonyl Common Reducing Agents (Lithium Borohydride) The reductions with LiBH4 are commonly carried out in THF or ether Note that nucleophilic attack occurs from the least hindered face of the 9:45 AM 9 carbonyl. Common Reducing Agents (Borohydrides) The Influence of Metal Cations on Reactivity As a result of the differences in reactivity between sodium borohydride and lithium borohydride, chemoselectivity of reduction can be achieved by a judicious choice of reducing agent. 9:45 AM 10 Common Reducing Agents (Sodium Cyanoborohydride) 9:45 AM 11 Common Reducing Agents (Reductive Amination with Sodium Cyanoborohydride) 9:45 AM 12 Lithium Aluminium Hydride Lithium aluminiumhydride reacts the same way as lithium borohydride. -

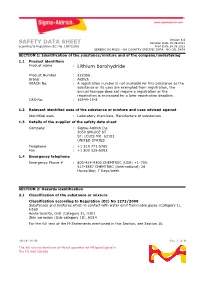

SAFETY DATA SHEET Revision Date 15.09.2021 According to Regulation (EC) No

Version 6.6 SAFETY DATA SHEET Revision Date 15.09.2021 according to Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006 Print Date 24.09.2021 GENERIC EU MSDS - NO COUNTRY SPECIFIC DATA - NO OEL DATA SECTION 1: Identification of the substance/mixture and of the company/undertaking 1.1 Product identifiers Product name : Lithium borohydride Product Number : 222356 Brand : Aldrich REACH No. : A registration number is not available for this substance as the substance or its uses are exempted from registration, the annual tonnage does not require a registration or the registration is envisaged for a later registration deadline. CAS-No. : 16949-15-8 1.2 Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Identified uses : Laboratory chemicals, Manufacture of substances 1.3 Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Company : Sigma-Aldrich Inc. 3050 SPRUCE ST ST. LOUIS MO 63103 UNITED STATES Telephone : +1 314 771-5765 Fax : +1 800 325-5052 1.4 Emergency telephone Emergency Phone # : 800-424-9300 CHEMTREC (USA) +1-703- 527-3887 CHEMTREC (International) 24 Hours/day; 7 Days/week SECTION 2: Hazards identification 2.1 Classification of the substance or mixture Classification according to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 Substances and mixtures which in contact with water emit flammable gases (Category 1), H260 Acute toxicity, Oral (Category 3), H301 Skin corrosion (Sub-category 1B), H314 For the full text of the H-Statements mentioned in this Section, see Section 16. Aldrich- 222356 Page 1 of 8 The life science business of Merck operates as MilliporeSigma in the US and Canada 2.2 Label elements Labelling according Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 Pictogram Signal word Danger Hazard statement(s) H260 In contact with water releases flammable gases which may ignite spontaneously. -

Operation Permit Application

Un; iy^\ tea 0 9 o Operation Permit Application Located at: 2002 North Orient Road Tampa, Florida 33619 (813) 623-5302 o Training Program TRAINING PROGRAM for Universal Waste & Transit Orient Road Tampa, Florida m ^^^^ HAZARDOUS WAb 1 P.ER^AlTTlNG TRAINING PROGRAM MASTER INDEX CHAPTER 1: Introduction Tab A CHAPTER 2: General Safety Manual Tab B CHAPTER 3: Protective Clothing Guide Tab C CHAPTER 4: Respiratory Training Program Tab D APPENDIX 1: Respiratory Training Program II Tab E CHAPTER 5: Basic Emergency Training Guide Tab F CHAPTER 6: Facility Operations Manual Tab G CHAPTER 7: Land Ban Certificates Tab H CHAPTER 8: Employee Certification Statement Tab. I CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION prepared by Universal Waste & Transit Orient Road Tampa Florida Introducti on STORAGE/TREATMENT PERSONNEL TRAINING PROGRAM All personnel involved in any handling, transportation, storage or treatment of hazardous wastes are required to start the enclosed training program within one-week after the initiation of employment at Universal Waste & Transit. This training program includes the following: Safety Equipment Personnel Protective Equipment First Aid & CPR Waste Handling Procedures Release Prevention & Response Decontamination Procedures Facility Operations Facility Maintenance Transportation Requirements Recordkeeping We highly recommend that all personnel involved in the handling, transportation, storage or treatment of hazardous wastes actively pursue additional technical courses at either the University of South Florida, or Tampa Junior College. Recommended courses would include general chemistry; analytical chemistry; environmental chemistry; toxicology; and additional safety and health related topics. Universal Waste & Transit will pay all registration, tuition and book fees for any courses which are job related. The only requirement is the successful completion of that course. -

Materials Chemistry Materials Chemistry

Materials Chemistry Materials Chemistry by Bradley D. Fahlman Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, MI, USA A C.I.P. Catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-1-4020-6119-6 (HB) ISBN 978-1-4020-6120-2 (e-book) Published by Springer, P.O. Box 17, 3300 AA Dordrecht, The Netherlands. www.springer.com Printed on acid-free paper First published 2007 Reprinted 2008 All Rights Reserved © 2008 Springer Science + Business Media B.V. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ............................................................ ix Chapter 1. WHAT IS MATERIALS CHEMISTRY? .................... 1 1.1 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES . ............................ 2 1.2 CONSIDERATIONS IN THE DESIGN OF NEW MATERIALS . 5 1.3 DESIGN OF NEW MATERIALS THROUGH A “CRITICAL THINKING”APPROACH................................... 6 Chapter 2. SOLID-STATE CHEMISTRY ............................ 13 2.1 AMORPHOUS VS.CRYSTALLINESOLIDS.................. 13 2.2 TYPES OF BONDING IN SOLIDS . ..................... 14 2.2.1 IonicSolids......................................... 14 2.2.2 Metallic Solids . ................................ 16 2.2.3 Molecular Solids. ................................ 19 2.2.4 CovalentNetworkSolids.............................. 21 2.3 THECRYSTALLINESTATE................................ 21 2.3.1 Crystal Growth Techniques . ..................... 23 2.3.2 TheUnitCell ....................................... 25 2.3.3 CrystalLattices...................................... 28 2.3.4 CrystalImperfections................................. 41 2.3.5 Phase-Transformation Diagrams. ..................... 47 2.3.6 Crystal Symmetry and Space Groups . -

Standard Thermodynamic Properties of Chemical

STANDARD THERMODYNAMIC PROPERTIES OF CHEMICAL SUBSTANCES ∆ ° –1 ∆ ° –1 ° –1 –1 –1 –1 Molecular fH /kJ mol fG /kJ mol S /J mol K Cp/J mol K formula Name Crys. Liq. Gas Crys. Liq. Gas Crys. Liq. Gas Crys. Liq. Gas Ac Actinium 0.0 406.0 366.0 56.5 188.1 27.2 20.8 Ag Silver 0.0 284.9 246.0 42.6 173.0 25.4 20.8 AgBr Silver(I) bromide -100.4 -96.9 107.1 52.4 AgBrO3 Silver(I) bromate -10.5 71.3 151.9 AgCl Silver(I) chloride -127.0 -109.8 96.3 50.8 AgClO3 Silver(I) chlorate -30.3 64.5 142.0 AgClO4 Silver(I) perchlorate -31.1 AgF Silver(I) fluoride -204.6 AgF2 Silver(II) fluoride -360.0 AgI Silver(I) iodide -61.8 -66.2 115.5 56.8 AgIO3 Silver(I) iodate -171.1 -93.7 149.4 102.9 AgNO3 Silver(I) nitrate -124.4 -33.4 140.9 93.1 Ag2 Disilver 410.0 358.8 257.1 37.0 Ag2CrO4 Silver(I) chromate -731.7 -641.8 217.6 142.3 Ag2O Silver(I) oxide -31.1 -11.2 121.3 65.9 Ag2O2 Silver(II) oxide -24.3 27.6 117.0 88.0 Ag2O3 Silver(III) oxide 33.9 121.4 100.0 Ag2O4S Silver(I) sulfate -715.9 -618.4 200.4 131.4 Ag2S Silver(I) sulfide (argentite) -32.6 -40.7 144.0 76.5 Al Aluminum 0.0 330.0 289.4 28.3 164.6 24.4 21.4 AlB3H12 Aluminum borohydride -16.3 13.0 145.0 147.0 289.1 379.2 194.6 AlBr Aluminum monobromide -4.0 -42.0 239.5 35.6 AlBr3 Aluminum tribromide -527.2 -425.1 180.2 100.6 AlCl Aluminum monochloride -47.7 -74.1 228.1 35.0 AlCl2 Aluminum dichloride -331.0 AlCl3 Aluminum trichloride -704.2 -583.2 -628.8 109.3 91.1 AlF Aluminum monofluoride -258.2 -283.7 215.0 31.9 AlF3 Aluminum trifluoride -1510.4 -1204.6 -1431.1 -1188.2 66.5 277.1 75.1 62.6 AlF4Na Sodium tetrafluoroaluminate -

Wo 2008/040002 A9

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) CORRECTED VERSION (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (43) International Publication Date (10) International Publication Number 3 April 2008 (03.04.2008) PCT WO 2008/040002 A9 (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/095 (2006.01) A61P 9/00 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, A61K 33/04 (2006.01) A61P 11/00 (2006.01) AT,AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY,BZ, CA, CH, AOlN 1/00 (2006.01) A61P 41/00 (2006.01) CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, A61P 7/00 (2006.01) A61P 43/00 (2006.01) ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KR KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, (21) International Application Number: LR, LS, LT, LU, LY,MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, PCT/US2007/079948 MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, SV, SY, (22) International Filing Date: TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, 28 September 2007 (28.09.2007) ZM, ZW (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (26) Publication Language: English kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, TM), 60/827,337 28 September 2006 (28.09.2006) US European (AT,BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT,LU, LV,MC, MT, NL, PL, (71) US): Applicant (for all designated States except FRED PT, RO, SE, SI, SK, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, HUTCHINSON CANCER RESEARCH CENTER GA, GN, GQ, GW, ML, MR, NE, SN, TD, TG). -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,381,492 B2 Turbeville Et Al

USOO9381492B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,381,492 B2 Turbeville et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jul. 5, 2016 (54) COMPOSITION AND PROCESS FOR (56) References Cited MERCURY REMOVAL U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS (71) Applicant: Sud-Chemie Inc., Louisville, KY (US) 4,094,777 A 6/1978 Sugier et al. 4.474,896 A 10, 1984 Chao (72) Inventors: Wayne Turbeville, Crestwood, KY 4,911,825 A * 3/1990 Roussel ................. C10G 45.04 (US);: Gregregisorynia, Korynta, Louisville, KY 5,409,522 A 4/1995. Durham et al. 208,251 R. (US); Todd Cole, Louisville, KY (US); 5,505,766 A 4/1996 Chang Jeffery L. Braden, New Albany, IN 5,607,496 A 3, 1997 Brooks (US) 5,827,352 A 10, 1998 Altman et al. 5,900,042 A 5/1999 Mendelsohn et al. 6,027,551 A 2/2000 Hwang et al. (73) Assignee: Clariant Corporation, Louisville, KY 6,136,281. A 10/2000 Meischen et al. (US) 6,451,094 B1 9/2002 Chang et al. 6,521,021 B1 2/2003 Pennline et al. c 6,699,440 B1 3/2004 Vermeulen (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 6,719,828 B1 4/2004 Lovellet al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 6,770,119 B2 8/2004 Harada et al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 180 days. 6,890,507 B2 5/2005 Chen et al. 6,962,617 B2 11/2005 Simpson 7,040,891 B1 5/2006 Giuliani (21) Appl. No.: 13/691.977 7,081,434 B2 7/2006 Sinha 7,238,223 B2 7/2007 Meegan, Jr. -

Selective Reduction of Halides with Lithium Borohydride in The

DAEHAN HWAHAK HWOEJEE (.Journal of the Korean Chemical Society) Vol. 27, No. 1. 1983 Printed in the Republic of Korea 수소화 붕소리튬을 이용한 다중작용기를 가진 화합물에서 할라이드의 선택환원 趙炳泰•尹能民十 서강대학교 이공대학 화학과 (1982. 8. 9 접수) Selective Reduction of Halides with Lithium Borohydride in the Multifunctional Compounds Byung Tae Cho and Nung Min Yoont Department of Chemistry, Sogang University, Seoul 121, Korea, (Received Aug. 9, 1982) 요 약. 한 분자내에 클로로, 니르로, 에스테르 및 니트릴기를 포함하는 할로겐 화합물에서 수소 화붕소리튬을 이용한 할로겐의 선택환원이 논의되었다. 브로모-4-클로로부탄은 96 %의 수득율로 I-클로로부탄으로, 브롬화 />-니트로벤질은 98 %의 수득율로 A니트로 톨루엔으로 환원되었으나 요 오도프로피온산 에 틸에스테르나4-브로모부티로니트릴의 경우 선택 환원의 수득율이 낮았다. 그러나 당 량의 피리딘 존재하에서 이 반응을 시키면 프로피온산 에틸에스테르는 93%, 부티로니트릴은 88% 로서 각각 선택환원의 수득율이 향상되었다. ABSTRACT. Selective reduction of halide (Br, I ) with lithium borohydride in halogen com pounds containing chloro, nitro, ester and nitrile groups was achieved satisfactorily, l-bromo-4- chlorobutane was reduced to 1-chlorobutane in 96% yield and the reduction of y)-nitrobenzyl bro mide gave />~nitrotoluene in 98 % yield. However, the selectivity on the reduction of ethyl 3- iodopropionate and 4-bromobutyronitrile required the presence of equimolar pyridine to give good yields of ethyl propionate (93 %) and w-butyronitrile (88 %), respectively. In ^competitive reduc tion of 1-bromoheptane and 2-bromoheptane, lithium borohydride reduced 1-bromoheptane pre ferentially in the molar ratio of 93: 7. and secondary iodides, bromides, chlorides). INTRODUCTION On the other hand, it was also realized that It was reported that both lithium aluminum remark사)ly mild reducing agents, sodium boro hydride and lithium triethylborohydride exhi hydride and sodium cyanoborohydride reduced bited exceptional utility for the reduction of successfully alkyl halides in dimethyl sulfoxide alkyl halides and tosylates.1,2 However, they or hexamethyl phosphoramide. -

Chemical Names and CAS Numbers Final

Chemical Abstract Chemical Formula Chemical Name Service (CAS) Number C3H8O 1‐propanol C4H7BrO2 2‐bromobutyric acid 80‐58‐0 GeH3COOH 2‐germaacetic acid C4H10 2‐methylpropane 75‐28‐5 C3H8O 2‐propanol 67‐63‐0 C6H10O3 4‐acetylbutyric acid 448671 C4H7BrO2 4‐bromobutyric acid 2623‐87‐2 CH3CHO acetaldehyde CH3CONH2 acetamide C8H9NO2 acetaminophen 103‐90‐2 − C2H3O2 acetate ion − CH3COO acetate ion C2H4O2 acetic acid 64‐19‐7 CH3COOH acetic acid (CH3)2CO acetone CH3COCl acetyl chloride C2H2 acetylene 74‐86‐2 HCCH acetylene C9H8O4 acetylsalicylic acid 50‐78‐2 H2C(CH)CN acrylonitrile C3H7NO2 Ala C3H7NO2 alanine 56‐41‐7 NaAlSi3O3 albite AlSb aluminium antimonide 25152‐52‐7 AlAs aluminium arsenide 22831‐42‐1 AlBO2 aluminium borate 61279‐70‐7 AlBO aluminium boron oxide 12041‐48‐4 AlBr3 aluminium bromide 7727‐15‐3 AlBr3•6H2O aluminium bromide hexahydrate 2149397 AlCl4Cs aluminium caesium tetrachloride 17992‐03‐9 AlCl3 aluminium chloride (anhydrous) 7446‐70‐0 AlCl3•6H2O aluminium chloride hexahydrate 7784‐13‐6 AlClO aluminium chloride oxide 13596‐11‐7 AlB2 aluminium diboride 12041‐50‐8 AlF2 aluminium difluoride 13569‐23‐8 AlF2O aluminium difluoride oxide 38344‐66‐0 AlB12 aluminium dodecaboride 12041‐54‐2 Al2F6 aluminium fluoride 17949‐86‐9 AlF3 aluminium fluoride 7784‐18‐1 Al(CHO2)3 aluminium formate 7360‐53‐4 1 of 75 Chemical Abstract Chemical Formula Chemical Name Service (CAS) Number Al(OH)3 aluminium hydroxide 21645‐51‐2 Al2I6 aluminium iodide 18898‐35‐6 AlI3 aluminium iodide 7784‐23‐8 AlBr aluminium monobromide 22359‐97‐3 AlCl aluminium monochloride -

2020 Emergency Response Guidebook

2020 A guidebook intended for use by first responders A guidebook intended for use by first responders during the initial phase of a transportation incident during the initial phase of a transportation incident involving hazardous materials/dangerous goods involving hazardous materials/dangerous goods EMERGENCY RESPONSE GUIDEBOOK THIS DOCUMENT SHOULD NOT BE USED TO DETERMINE COMPLIANCE WITH THE HAZARDOUS MATERIALS/ DANGEROUS GOODS REGULATIONS OR 2020 TO CREATE WORKER SAFETY DOCUMENTS EMERGENCY RESPONSE FOR SPECIFIC CHEMICALS GUIDEBOOK NOT FOR SALE This document is intended for distribution free of charge to Public Safety Organizations by the US Department of Transportation and Transport Canada. This copy may not be resold by commercial distributors. https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/hazmat https://www.tc.gc.ca/TDG http://www.sct.gob.mx SHIPPING PAPERS (DOCUMENTS) 24-HOUR EMERGENCY RESPONSE TELEPHONE NUMBERS For the purpose of this guidebook, shipping documents and shipping papers are synonymous. CANADA Shipping papers provide vital information regarding the hazardous materials/dangerous goods to 1. CANUTEC initiate protective actions. A consolidated version of the information found on shipping papers may 1-888-CANUTEC (226-8832) or 613-996-6666 * be found as follows: *666 (STAR 666) cellular (in Canada only) • Road – kept in the cab of a motor vehicle • Rail – kept in possession of a crew member UNITED STATES • Aviation – kept in possession of the pilot or aircraft employees • Marine – kept in a holder on the bridge of a vessel 1. CHEMTREC 1-800-424-9300 Information provided: (in the U.S., Canada and the U.S. Virgin Islands) • 4-digit identification number, UN or NA (go to yellow pages) For calls originating elsewhere: 703-527-3887 * • Proper shipping name (go to blue pages) • Hazard class or division number of material 2. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2007/0078113 A1 Roth Et Al

US 20070078113A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2007/0078113 A1 Roth et al. (43) Pub. Date: Apr. 5, 2007 (54) METHODS, COMPOSITIONS AND Publication Classification ARTICLES OF MANUFACTURE FOR ENHANCING SURVIVABILITY OF CELLS, (51) Int. Cl. TISSUES, ORGANS, AND ORGANISMS A6II 3/66 (2006.01) A 6LX 3/555 (2006.01) (76) Inventors: Mark B. Roth, Seattle, WA (US); Mike A6II 3/85 (2006.01) Morrison, Seattle, WA (US); Eric A6II 3 L/65 (2006.01) Blackstone, Seattle, WA (US); Dana A 6LX 3L/275 (2006.01) Miller, Seattle, WA (US) A6II 3L/26 (2006.01) A 6LX 3L/095 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: A6II 3L/21 (2006.01) FULBRIGHT & UAWORSK LLP. (52) U.S. Cl. .......................... 514/114: 514/184: 514/706; 6OO CONGRESS AVE. 514/126; 514/553: 514/514; SUTE 24 OO 514/526; 514/621 AUSTIN, TX 78701 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (21) Appl. No.: 11/408,734 The present invention concerns the use of oxygen antago (22) Filed: Apr. 20, 2006 nists and other active compounds for inducing stasis or pre-stasis in cells, tissues, and/or organs in vivo or in an organism overall, in addition to enhancing their Survivabil Related U.S. Application Data ity. It includes compositions, methods, articles of manufac ture and apparatuses for enhancing Survivability and for (60) Provisional application No. 60/673,037, filed on Apr. achieving stasis or pre-stasis in any of these biological 20, 2005. Provisional application No. 60/673,295, materials, so as to preserve and/or protect them. In specific filed on Apr. -

"Sony Mobile Critical Substance List" At

Sony Mobile Communications Public 1(16) DIRECTIVE Document number Revision 6/034 01-LXE 110 1408 Uen C Prepared by Date SEM/CGQS JOHAN K HOLMQVIST 2014-02-20 Contents responsible if other than preparer Remarks This document is managed in metaDoc. Approved by SEM/CGQS (PER HÖKFELT) Sony Mobile Critical Substances Second Edition Contents 1 Revision history.............................................................................................3 2 Purpose.........................................................................................................3 3 Directive ........................................................................................................4 4 Application ....................................................................................................4 4.1 Terms and Definitions ...................................................................................4 5 Comply to Sony Technical Standard SS-00259............................................6 6 The Sony Mobile list of Critical substances in products................................6 7 The Sony Mobile list of Restricted substances in products...........................7 8 The Sony Mobile list of Monitored substances .............................................8 It is the responsibility of the user to ensure that they have a correct and valid version. Any outdated hard copy is invalid and must be removed from possible use. Public 2(16) DIRECTIVE Document number Revision 6/034 01-LXE 110 1408 Uen C Substance control Sustainability is the backbone