Community Forestry in Nepal: What Have We Learned ?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

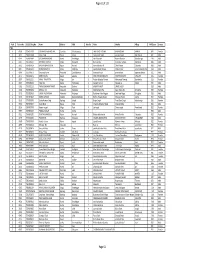

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

National Shelter Cluster Meeting

National Shelter Cluster Meeting Kathmandu 22 July 11am Shelter Cluster Nepal ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter 1 Agenda 1. Welcome 2. Update from Government of Nepal (DUDBC) 3. Information Management 4. CCCM - DTM Round 3 5. Central Hub Update 6. Eastern Hub Update 7. Technical Update 8. Update on Recovery & Reconstruction Working Group 9. AOB Shelter Cluster Nepal ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter 2 Update from Government of Nepal (DUDBC) Shelter Cluster Nepal ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter 3 Information Management on Sheltercluster.org Brief introduction to the website Shelter Cluster Nepal ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter 4 National Update Shelter Cluster Nepal ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter 5 District Update . Emergency Shelter: . Self-Recovery: – Most Covered: Dolakha, – Most Covered: Rasuwa, Gorkha, Sindhulpalchok, Gorka, Rasuwa, Sinhupalchok Okhald. – Least Covered: All others <26% – Least covered: Ramechap, Makwanpur, Kavre, Bhaktapur, KTM Southeast Hub Northeast Hub West Hub Central Hub Total Damage (HH) according to GoN 13,138 28,225 39,916 73,647 52,000 66,636 62,461 32,054 58,262 87,726 25,508 62,143 27,990 9,450 639,156 Percentage (%) of total Damaged HHs in 14 2% 4% 6% 12% 8% 10% 10% 5% 9% 14% 4% 10% 4% 1% 100% Priority Districts Emergency: Tarpaulin + Tent Okhaldhunga Sindhuli Ramechhap Kabhrepalanchok Dolakha Sindhupalchok Dhading Makawanpur Gorkha Kathmandu Lalitpur Nuwakot Bhaktapur Rasuwa Grand Total Completed or Ongoing -

Nepal Led Diary

NEPAL L.E.D. DIARY – JULY 2008 DIARY EXTRACTS: MONTH IN PERSPECTIVE : FEATURE – L.E.D. PROGRAMMING UPDATE FROM DHANUSHA & RAMEHHCAP : MONTHLY HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE L.E.D. GREEN CAFÉ : DIARY ENTRIES AUGUST 2008 MONTH IN PERSPECTIVE While the July LED Diary feature was to have been “Eco-Enterprise Value Chain Upgrading”, it was decided to devote this month’s feature instead to a mid-year status overview on LED Programming in Dhanusha and Ramechhap Districts to facili- tate upcoming National Steering Committee and LED Forum meetings in August as well as ILO EmPLED’s half-yearly report- ing. The emphasis during July 2008 has been on assisting the District LED stakeholders to continue to package the consensus LED strategies and activities from April-May 2008, and roll-out related action programmes and activities (i.e. support projects and interventions). Eco-enterprise will however definitely feature prominently in a forthcoming issue. The main challenge aris- ing from the consensus strategies of the Dhanusha and Ramechhap LED Forums was to flexibly package the strategies and activities in a complimentary manner for demonstrating how LED can inclusively bring the global employment agenda to the local level. The feature kicks-off with a quick refresher on what LED is about followed by the overview of the LED action pro- grammes in Dhanusha and Ramechhap Districts. Some programme resource allocations are current estimates and may be subject to amendment by the LED Forums in response to important emerging issues such as the global food crisis. FEATURE – LED PROGRAMMING UPDATE FROM DHANUSHA & RAMECHHAP DISTRICTS RECAP – “LOCAL ECONOMIC DEVELEOPMENT (LED) IN-A-BLINK” (ILO “LED OUTLOOK 2008”) Globalization has changed the rules that govern the world’s economies, connect- ing national, regional and local economies more than ever before. -

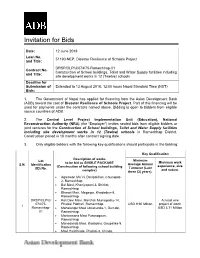

DRSP/CLPIU/074/75-Ramechhap-01 Contract No

Invitation for Bids Date: 12 June 2018 Loan No. 51190-NEP: Disaster Resilience of Schools Project and Title: DRSP/CLPIU/074/75-Ramechhap-01 Contract No. Construction of School buildings, Toilet and Water Supply facilities including and Title: site development works in 12 (Twelve) schools Deadline for Submission of Extended to 13 August 2018, 12:00 hours Nepal Standard Time (NST) Bids: 1. The Government of Nepal has applied for financing from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) toward the cost of Disaster Resilience of Schools Project. Part of this financing will be used for payments under the contracts named above. Bidding is open to bidders from eligible source countries of ADB. 2. The Central Level Project Implementation Unit (Education), National Reconstruction Authority (NRA) (the “Employer”) invites sealed bids from eligible bidders or joint ventures for the Construction of School buildings, Toilet and Water Supply facilities including site development works in 12 (Twelve) schools in Ramechhap District. Construction period is 18 months after contract signing date. 3. Only eligible bidders with the following key qualifications should participate in the bidding: Key Qualification Description of works Minimum Lot Minimum work to be bid as SINGLE PACKAGE Average Annual S.N. Identification experience, size (Construction of following school building Turnover (Last (ID) No. and nature. complex) three (3) years). • Agleswori Ma Vi, Dimipokhari, Chunapati- 2, Ramechhap • Bal Mavi, Khaniyapani-3, Bhirkot, Ramechhap • Bharati Mavi, Megarpa, Khadadevi-8, -

Politics of R Esistance

Politics of Resistance Politics Tis book illustrates an exciting approach to understanding both Indigenous Peoples of Nepal are searching for the state momentous and everyday events in the history of South Asia. It which recognizes and refects their identities. Exclusion of advances notions of rupture and repair to comprehend the afermath indigenous peoples in the ruling apparatus and from resources of natural, social and personal disasters, and demonstrates the of the “modern states,” and absence of their representation and generality of the approach by seeking their historical resolution. belongingness to its structures and processes have been sources Te introduction of rice milling technology in a rural landscape of conficts. Indigenous peoples are engaged in resistance in Bengal,movements the post-cold as the warstate global has been shi factive in international in destroying, relations, instead of the assassinationbuilding, their attempt political, on a economicjournalist and in acultural rented institutions.city house inThe Kathmandu,new constitution the alternate of 2015and simultaneousfailed to address existence the issues, of violencehence the in non-violentongoing movements,struggle for political,a fash feconomic,ood caused and by cultural torrential rights rains and in the plainsdemocratization of Nepal, theof the closure country. of a China-India border afer the army invasionIf the in Tibet,country and belongs the appearance to all, if the of outsiderspeople have in andemocratic ethnic Taru hinterlandvalues, the – indigenous scholars in peoples’ this volume agenda have would analysed become the a origins, common anatomiesagenda and ofdevelopment all. If the state of these is democratic events as andruptures inclusive, and itraised would interestingaddress questions the issue regarding of justice theirto all. -

NEPAL: Ramechhap District

NEPAL: Ramechhap District - Manthali Municipality and Ramechhap Municipality HRHRRPRPHRRP 85°57'E 85°58'E 85°59'E 86°0'E 86°1'E 86°2'E 86°3'E 86°4'E 86°5'E 86°6'E 86°7'E 86°8'E 86°9'E 86°10'E 86°11'E 86°12'E Legend 27°27'N ¹½ School Chhap Kauseni Jiri Village Name Kalleri Kalleri Highway 27°26'N Kharpani 27°26'N District Road Patale Other Road Banre Ward no: 14 Kauchini Bharuwa Major Trail Ward no: 15 27°25'N Thakle Local Trail 27°25'N Ward no: 16 Kauchinibesi Municipal Boundary Pokhari Karambote Simpani Ward no: 4 Gogane Piple Ward Boundary Mugikholagaun Tekanpur " " " " " " Pokhari Dure Birta " "" Settlement Anpchaur Kabhre Tekanpur 27°24'N Rolini Kathjor Dunde Badi Muhan Ward no: 3 Mugikholagaun Tekanpur Kartike Piple Ward no: 5 Kuwapani Forest 27°24'N Akase Ward no: 13 Ramche Dandagaun Patale Odare Dahalgaun Bhatauli Kathjor Cultivation Thanti Thanti Dhand Gadwari Puranagaun Bhadaure Gairigaun Grassland Ward no: 2 Siddhidanda Manthali N.P. Archale Archale Pallo Gairathok Sani Madhau Ward no: 6 Thuli Madhau 27°23'N Mugitar Manthalighat Hariswanr Bush Nawalpur Khadwari 27°23'N Manthali Bhanjyang Thulitar Ralitar Gahate Ward no: 7 Dandagaun Kundahar Bhainsesur Sand / Gravel Kunauri Gairithok Sanpmare Thuli Madhu Hattitar Kunauri Kundhar Rahaltar Wallo Gairathok River / Stream Ward no: 1 Samalithan Kabilas Masantar Ritthabote Kalianp Dare Ward no: 10 Masantar 27°22'N Pond / Lake Dandakharka Pokhare Pandegaun Samalithan Deurali Manthali Thulachaur Salupati 27°22'N Dandakhoriya Ward no: 12 Bitar Kaijale Damaidanda Dandagaun Saunepani Keworepani -

Ramechhap VDC

Poverty Alleviation Fund Earthquake Response Program Seven Days Mason Training List of Participants District: Ramechhap VDC: Rakathum Training Duration: April 28, 2017-May 4, 2017 Venue: Lubu Partner Organization: Nepal MSR Centre SN Participant Name Address Citizen No Age Gender Contact No 1. Palten Tamang Chhapabot, Rakathum 48306 40 Male 9818911615 2. Chamar Dong Chapadi, Rakathum 213052/346 40 Male 9819679014 3. Dhan Bahadur Chapadi, Rakathum 906 57 Male 9810169447 Tamang 4. Sonam Lama Labhu, Rakathum 40753 46 Male 9861591145 5. Chuntui Lama Khanigaun, Rakathum 211052-1222 34 Male 9818911615 6. Ramita Kumari Dharapani, Rakathum 461 37 Female 9810216040 Kadel 7. Gam Bahadur Dharapani, Rakathum 62366 63 Male 9823683500 Shrestha 8. Raj Kumar Shrestha Ghatte, Bethan 65411 36 Male 9818722056 9. Purna Bahadur Chapadi, Rakathum 911 33 Male - Pulami 10. Man Bahadur Chapadi, Rakathum 910 55 Male - Khadka 11. Binod Majhi Chihadi, Bethan 38100 42 Male 9818804256 12. Rajkrishna Shrestha Jugepani, Bethan 3859 47 Male 9802165681 13. Jakta Bahadur Amaldanda, Bethan 211047/3093 62 Male 9807634872 Shrestha 4 14. Dal Bahadur Lada, Bethan 39066 31 Male 9813258659 Shrestha 15. Dambar Bahadur Ghatte, Bethan 2657 44 Male 9800877224 Tamang 16. Harkha Bahadur Garkot, Bethan 57934 55 Male 9803479249 Magar 17. Karna Bahadur Chapadi, Rakathum 213052/336 50 Male 9840201118 Magar 18. Dhurba Bahadur Lamatol, Bethan 1634/050 57 Male 9817829803 Khatri (Ghimire) 19. Sanukaji Paudel Chhapabot, Rakathum 48306 49 Male 9818911615 20. Bikram Tamang Chapadi, Rakathum 213052/346 25 Male 9819679014 21. Ram Bahadur Chapadi, Rakathum 906 43 Male 9810169447 Tamang 22. Man Bahadur Labhu, Rakathum 40753 54 Male 9861591145 Tamang 23. -

Chap. 3 Agriculture Development of Objective Districts

CHAP. 3 AGRICULTURE DEVELOPMENT OF OBJECTIVE DISTRICTS This chapter is organized into seven sections. Section 3.1 provides basic data of the five objective districts. Section 3.2 discusses road conditions of each district. Section 3.3 describes the general situation of each district. Section 3.4 provides district development plans, budgets and priorities. Human resource and administrative structures of the DDC and District Technical Office (DTO) are also discussed in this section. Section 3.5 depicts the districts agriculture development polices and programs. Agricultural production in survey districts are presented in Section 3.6. Section 3.7 depicts agricultural marketing situations in the survey districts. 3.1 Basic Data of the Objective Districts The basic data of the five Districts such as area, population, literacy rate and poverty incidence are shown in the following Table 3.1: Table 3.1 Basic Data of the Objective Districts S urvey Districts No Particulars Unit Kavre- Whol e Ne pal Dolakha Ramechhap Sindhuli Mahottari palanchok 1 Area Sq. Km 2,191 1,546 1,396 2,491 1,002 147,181 2 Population 1000 Nos. 204.2 212.4 385.7 280 553.5 22,736.90 3 Male 1000 Nos. 100 100.8 188.9 139.3 287.9 11,563.90 4 Female 1000 Nos. 104 111.6 196.7 140.5 265.6 11,587.50 5 Sex Ratio % 96 90 96 99 108 100 6 Total Households 1000 Nos. 43.2 40.4 70.5 48.8 94.2 4,174.40 7 Average Household size Nos. 4.73 5.26 5.47 5.74 5.87 5.44 Nos./ Sq. -

Global Initiative on Out-Of-School Children

ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Government of Nepal Ministry of Education, Singh Darbar Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 4200381 www.moe.gov.np United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Institute for Statistics P.O. Box 6128, Succursale Centre-Ville Montreal Quebec H3C 3J7 Canada Telephone: +1 514 343 6880 Email: [email protected] www.uis.unesco.org United Nations Children´s Fund Nepal Country Office United Nations House Harihar Bhawan, Pulchowk Lalitpur, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 5523200 www.unicef.org.np All rights reserved © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 2016 Cover photo: © UNICEF Nepal/2016/ NShrestha Suggested citation: Ministry of Education, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Global Initiative on Out of School Children – Nepal Country Study, July 2016, UNICEF, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016. ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children © UNICEF Nepal/2016/NShrestha NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Tel.: Government of Nepal MINISTRY OF EDUCATION Singha Durbar Ref. No.: Kathmandu, Nepal Foreword Nepal has made significant progress in achieving good results in school enrolment by having more children in school over the past decade, in spite of the unstable situation in the country. However, there are still many challenges related to equity when the net enrolment data are disaggregated at the district and school level, which are crucial and cannot be generalized. As per Flash Monitoring Report 2014- 15, the net enrolment rate for girls is high in primary school at 93.6%, it is 59.5% in lower secondary school, 42.5% in secondary school and only 8.1% in higher secondary school, which show that fewer girls complete the full cycle of education. -

170110 Ramechhap Copy

District Profile - Ramechhap (as of 10 Jan 2017) HRRP This district profile outlines the current activities by partner organisations (POs) in post-earthquake recovery and reconstruction. It is based on 4W and secondary data collected from POs on their recent activities pertaining to housing sector. Further, it captures a wide range of planned, ongoing and completed activities within the HRRP framework. For additional information, please refer to the HRRP dashboard. FACTS AND FIGURES Population: 202,6461 45 VDCs and 2 municipalities Damage Status - Private Structures Type of housing walls Ramechhap National Mud-bonded bricks/stone 95% 41% Cement-bonded bricks/stone 3% 29% Damage Grade (3-5) 49,345 Other 2% 30% Damage Grade (1-2) 9,267 % of households who own 95% 85% Total 58,6122 their housing unit (Census 2011)1 NEWS & UPDATES 1. HRRP team, along with NRA engineers, visited Pakarbas, Dimipokhari, Doramba, Tokarpur and Goswara VDCs. It was observed that there are not enough masons and artisans for the ongoing reconstruction process. 2. The Orientation on Inspection SOP for POs was held on 18 Jan. Participants were keen to know when the retrofitting guidelines and list of eligible households would be released and to understand how this will be operationalised. Concerns were also raised regarding the high cost and transportation challenges for concrete constructions. 3. According to DLPIU, as of 10 Jan, 1,448 HHs have started the reconstruction process and 338 HHs have already completed prior to inspection process. Based on field observation and experience, houses which has already been reconstructed or in process of reconstruction will not comply to checklist. -

Section 3 Zoning

Section 3 Zoning Section 3: Zoning Table of Contents 1. OBJECTIVE .................................................................................................................................... 1 2. TRIALS AND ERRORS OF ZONING EXERCISE CONDUCTED UNDER SRCAMP ............. 1 3. FIRST ZONING EXERCISE .......................................................................................................... 1 4. THIRD ZONING EXERCISE ........................................................................................................ 9 4.1 Methods Applied for the Third Zoning .................................................................................. 11 4.2 Zoning of Agriculture Lands .................................................................................................. 12 4.3 Zoning for the Identification of Potential Production Pockets ............................................... 23 5. COMMERCIALIZATION POTENTIALS ALONG THE DIFFERENT ROUTES WITHIN THE STUDY AREA ...................................................................................................................................... 35 i The Project for the Master Plan Study on High Value Agriculture Extension and Promotion in Sindhuli Road Corridor in Nepal Data Book 1. Objective Agro-ecological condition of the study area is quite diverse and productive use of agricultural lands requires adoption of strategies compatible with their intricate topography and slope. Selection of high value commodities for promotion of agricultural commercialization