Chap. 3 Agriculture Development of Objective Districts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Safeguard Due Diligence Report

Rural Connectivity Improvement Project (RRP NEP 48218) Social Safeguard Due Diligence Report Project Number: 48218-003 July 2017 Nepal: Rural Connectivity Improvement Project Prepared by Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads for the Asian Development Bank. This social safeguard due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. RURAL CONNECTIVITY IMPROVEMENT PROJECT NEPAL Social Safeguards Due Diligence Report July 2017 Prepared by PPTA Consultants On behalf of Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) Table of Contents Chapter 1 –Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Description .............................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2 - Due Diligence of Social Safeguards ........................................................................ 7 2.1 Methodology used to carry out the due diligence ............................................... -

PROPOSED HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT TAMAKOSHI 3 (TA3) August 2009 1

Information Brochure 01 PROPOSED HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT TAMAKOSHI 3 (TA3) August 2009 1 Information on the Proposed Tamakoshi 3 (TA3) Hydroelectric Project The Proponent/Developer for the project with new boundaries between SN Power is a growing international renewable Tamakoshi-Singati confl uence, and about 100 m energy company with projects in Asia, Latin upstream of the Tamakoshi bridge, at Kirnetar America and Africa. SN Power is a long-term was obtained on March 6th 2009. The TA-2 and industrial investor and is committed to social TA-3 projects have now been combined into one, and environmental sustainability throughout its i.e. the Tamakoshi 3 (TA3). The installed capacity business. The company’s current portfolio includes of the amended licence is 600 MW. hydropower projects in Nepal (Khimti Hydropower TA3 Project is located in Dolakha and Ramechhap Plant), India, the Phillipines, Sri Lanka, Chile, Peru districts. The proposed project will utilize the and Brazil. SN Power was established in 2002 fl ow of Tamakoshi River to generate electricity as a Norwegian limited company owned by by diverting the river at Betane and discharging Stratkraft, Norway’s largest utility company, and the water back into the river near Kirnetar. The Norfund, Norwegian state’s investment fund for project is under the optimization process and private companies in developing countries. In the various options are under evaluation. course of seven years, SN Power has established a strong platform for long-term growth. SN Power The project is a Peak Run-of-River (PROR) type is headquartered in Oslo, Norway. project. It is proposed to build a 102 m high dam near Betane to create a reservoir. -

3702-NEP: Disaster Resilience of Schools Project and Title: DRSP/CLPIU/076/77-Kavre-02 Contract No

Invitation for Bids Date: 24 September 2019 Loan No. 3702-NEP: Disaster Resilience of Schools Project and Title: DRSP/CLPIU/076/77-Kavre-02 Contract No. Construction of School Buildings, Toilet and Water Supply Facilities and Title: including Site Development Works in Nine (9) Schools of Kavrepalanchok District Deadline for Submission of 8 November 2019, 12:00 hours Nepal Standard Time (NST) Bids: 1. The Government of Nepal has received a financing from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) toward the cost of Disaster Resilience of Schools Project (DRSP). Part of this financing will be used for payments under the contract named above. Bidding is open to bidders from eligible source countries of ADB. 2. The Central Level Project Implementation Unit (Education), National Reconstruction Authority (NRA) (the “Employer”) invites sealed bids from eligible bidders or joint ventures for the Construction of School Buildings, Toilet and Water Supply Facilities including Site Development Works in Nine (9) Schools of Kavrepalanchok District. Construction period is 18 months after contract signing date. 3. Only eligible bidders with the following key qualifications should participate in the bidding: Key Qualification Minimum Description of works Minimum Lot work to be bid as SINGLE PACKAGE Average Annual S.N. Identification experience, (Construction of following school building Turnover (Last (ID) No. size and complex) three (3) years). nature. • Bhaleswor Mavi, Malpi, Panauti Municipality-8 • Dedithumka Mavi, Mandan Deupur Municipality-9 • Gyaneswori Mavi, Padalichaur, Anaikot-1 • Himalaya Mavi, Pipalbot, Rosh RM-6 At least one (1) • Laxmi Narayan Mavi, Narayantar, Roshi RM-2 DRSP/CLPIU/0 USD 7.00 Million project of Saraswati Mavi, Bhugdeu, Bethanchok RM-6 1 76/77-Kavre -02 • worth USD • Sarbamangala Mavi, Aglekot, Panchkhal Municipality-3 2.52 Million. -

Editorial Board

Editorial Board Chief Editor Prof. Dr. Prem Sagar Chapagain Editors Dr. Ashok Pande Dr. Anila Jha Managing Editor Hemanta Dangal This views expressed in the articles are soley of the individual authors and do not nec- essarily reflect the views ofSocial Protection Civil Society Network-Nepal. © Social Protection Civil Society Network (SPCSN)-Nepal About the Journal With an objective to bring learnings, issues and voices on social protection through experts in regard to inform the social protection audiences, practitioners, stakeholders and actors as well as to suggest policymakers to adequately design social protection programs to fill the gaps and delivery transparency and accountability, Social Protection Civil Society Network (SPCSN) expects to publish the introductory issue of Journal of Social Protection in both print and online versions. Review Process This journal was published by Social Protection Civil Society Network (SPCSN) with supports of Save the Children Nepal Country Office in collaboration with Save the Children Finland & Ministry of Foreign Affairs Finland and with management supports from Children, Woman in Social Service and Human Rights (CWISH), Nepal. Editorial and Business Office Published by SPCSN Buddhanagar, Kathmandu Email: [email protected] Website: www.spcsnnepal.org Social Protection Civil Society Network (SPCSN) ISSN: ....................... Designed by: Krishna Subedi Printed at: .................... Journal of Social Protection, 2020 Volumn 1 December 2020 Contents Boosting the Impact of Nepal’s Child Grant through a Parenting Intervention ............................................................................................. 1-10 - Disa Sjöblom Social Protection in Health: Characteristics and Coverage of Health Insurance Program in Nepal ................................................... 11-26 - Geha Nath Khanal and Bhagawan Regmi Making Shock Responsive Social Protection System in Nepalese Context .................................................................................... -

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal

FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF NEPAL MINISTRY OF IRRIGATION MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE DEVELOPMENT FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF NEPAL NEPAL AGRICULTURE RESEARCH COUNCIL MINISTRY OF IRRIGATION MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE DEVELOPMENT NEPAL AGRICULTUREPREPARATORY RESEARCH SURVEY COUNCIL ON JICA'S COOPERATION PROGRAM FOR AGRICULTUREPREPARATORY AND RURAL SURVEY DEVELOPMENT IN NEPALON JICA'S COOPERATION PROGRAM - FOODFOR AGRICULTURE PRODUCTION ANDAND AGRICULTURERURAL DEVELOPMENT IN TERAI - IN NEPAL - FOOD PRODUCTION AND AGRICULTURE IN TERAI - FINAL REPORT MAIN REPORT FINAL REPORT MAIN REPORT OCTOBER 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY OCTOBER(JICA) 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONALNIPPON KOEI COOPERATION CO., LTD. AGENCY VISION AND SPIRIT(JICA) FOR OVERSEAS COOPERATION (VSOC) CO., LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. C.D.C. INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION VISION AND SPIRIT FOR OVERSEAS COOPERATION (VSOC) CO., LTD. 4R C.D.C. INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION JR 13 - 031 FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF NEPAL MINISTRY OF IRRIGATION MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE DEVELOPMENT FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF NEPAL NEPAL AGRICULTURE RESEARCH COUNCIL MINISTRY OF IRRIGATION MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE DEVELOPMENT NEPAL AGRICULTUREPREPARATORY RESEARCH SURVEY COUNCIL ON JICA'S COOPERATION PROGRAM FOR AGRICULTUREPREPARATORY AND RURAL SURVEY DEVELOPMENT IN NEPALON JICA'S COOPERATION PROGRAM - FOODFOR AGRICULTURE PRODUCTION ANDAND AGRICULTURERURAL DEVELOPMENT IN TERAI - IN NEPAL - FOOD PRODUCTION AND AGRICULTURE IN TERAI - FINAL REPORT MAIN REPORT FINAL REPORT MAIN REPORT OCTOBER 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL -

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal Volumes: Volume I : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 1 Volume II : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 2 Volume III : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 3 Volume IV : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 4 Volume V : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 5 Volume VI : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 6 Volume VII : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 7 Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Department of Forest Research and Survey Kathmandu July 2017 © Department of Forest Research and Survey, 2017 Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part should mention the title and credit DFRS. Citation: DFRS, 2017. Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal. Department of Forest Research and Survey (DFRS). Kathmandu, Nepal Prepared by: Coordinator : Dr. Deepak Kumar Kharal, DG, DFRS Member : Dr. Prem Poudel, Under-secretary, DSCWM Member : Rabindra Maharjan, Under-secretary, DoF Member : Shiva Khanal, Under-secretary, DFRS Member : Raj Kumar Rimal, AFO, DoF Member Secretary : Amul Kumar Acharya, ARO, DFRS Published by: Department of Forest Research and Survey P. O. Box 3339, Babarmahal Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: 977-1-4233510 Fax: 977-1-4220159 Email: [email protected] Web: www.dfrs.gov.np Cover map: Front cover: Map of Forest Cover of Nepal FOREWORD Forest of Nepal has been a long standing key natural resource supporting nation's economy in many ways. Forests resources have significant contribution to ecosystem balance and livelihood of large portion of population in Nepal. Sustainable management of forest resources is essential to support overall development goals. -

District Profile - Kavrepalanchok (As of 10 May 2017) HRRP

District Profile - Kavrepalanchok (as of 10 May 2017) HRRP This district profile outlines the current activities by partner organisations (POs) in post-earthquake recovery and reconstruction. It is based on 4W and secondary data collected from POs on their recent activities pertaining to housing sector. Further, it captures a wide range of planned, ongoing and completed activities within the HRRP framework. For additional information, please refer to the HRRP dashboard. FACTS AND FIGURES Population: 381,9371 75 VDCs and 5 municipalities Damage Status - Private Structures Type of housing walls Kavrepalanchok National Mud-bonded bricks/stone 82% 41% Cement-bonded bricks/stone 14% 29% Damage Grade (3-5) 77,963 Other 4% 30% Damage Grade (1-2) 20,056 % of households who own 91% 85% Total 98,0192 their housing unit (Census 2011)1 NEWS & UPDATES 1. A total of 1,900 beneficiaries as per District Technical Office (DTO/DLPIU) have received the Second Tranche in Kavre. 114 beneficiaries within the total were supported by Partner Organizations. 2. Lack of proper orientations to the government officials and limited coordination between DLPIU engineers and POs technical staffs are the major reconstruction issues raised in the district. A joint workshop with all the district authorities, local government authorities and technical persons was agreed upon as a probable solution in HRRP Coordination Meeting dated April 12, 2017. HRRP - Kavrepalanchok HRRP © PARTNERS SUMMARY AND HIGHLIGHTS3 Partner Organisation Implementing Partner(s) ADRA NA 2,110 ARSOW -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Landslide Inventory, Characterization and Engineering Design for Mitigation Works of Chure Area in Ten Districts

LANDSLIDE INVENTORY, CHARACTERIZATION AND ENGINEERING DESIGN FOR MITIGATION WORKS OF CHURE AREA IN TEN DISTRICTS Submitted to: Submitted by: Government of Nepal Central Department of Environmental President Chure-Tarai Madhesh Science Conservation Development Board Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur Kathmandu September, 2016 © September 2016 President Chure-Tarai Madhesh Conservation Development Board and Central Department of Environmental Science, Tribhuvan University Citation: TU-CDES (2016). Landslide Inventory Characterization and Engineering Design for Mitigation Works of Chure Area in Ten Districts. Central Department of Environmental Science, Tribhuvan University and Government of Nepal, President Chure-Tarai Madhesh Conservation Development Board, Kathmandu. Project Steering Committee Chair Dr. Annapurna Das, Secretary , PCTMCDB/GoN Prof. Dr. Madan Koirala, Professor, TU-CDES Member Prof. Dr. Kedar Rijal, Head of Department, TU-CDES Member Prof. Dr. Rejina Maskey, Project Team Leader, TU-CDES Member Dr. Prem Paudel, Under Secretary, PCTMCDB/GoN Member Dr. Subodh Dhakal, Project Coordinator, TU-CDES Member Mr. Gehendra Keshari Upadhya, Joint Secretary , PCTMCDB/GoN Member Mr. Pashupati Koirala, Under- Secretary, PCTMCDB/GoN Project Team Team Leader Prof. Dr. Rejina Maskey Project Co-ordinator Dr. Subodh Dhakal Geo-Technical Engineer Dr. Ram Chandra Tiwari GIS Expert Mr. Ajay Bhakta Mathema Geologist Mr. Suman Panday Assistant Geologist Mr. Niraj Bal Tamang Assistant GIS Analyst Mr. Padam Bahadur Budha Assistant GIS Analyst Ms. Shanta Banstola Social Surveyor Mr. Kumod Lekhak Field Assistant Mr. Nabin Nepali Review Technical Reviewer: Dr. Ranjan Kumar Dahal English Reviewer: Dr. Dinesh Raj Bhuju ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Hazards like earthquake, landslide, soil erosion and sedimentation all shape the landscape and relief of the Himalaya. Land degradation of the Chure area of Nepal is primarily contributed by different types of landslides and mass wasting phenomena. -

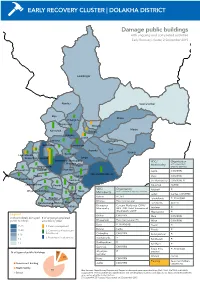

Early Recovery Cluster | Dolakha District

EARLY RECOVERY CLUSTER | DOLAKHA DISTRICT Damage public buildings with ongoing and completed activities Early Recovery cluster, 2 September 2015 Lamabagar Alambu Gaurishankar Bigu Khare Chilangkha Khopachagu Worang Marbu Kalinchok Bulung Babare Laduk Lapilang Changkhu Sundrawati Lamidanda Jhyanku Suri Syama Boch Sunkhani Lakuridanda Suspa Kshyamawati Jungu Bhimeswor Municipality VDC/ Organisation Chhetrapa Municipality with completed/ Magapauwa Kabre ongoing activities Bhusaphedi Katakuti Namdru Japhe CWV/RRN JIRI MUNICIPALITY Phasku Mirge Jhule CWV/RRN Dodhapokhari Gairimudi Jiri Municipality CWV/RRN, PI Bhirkot Sailungeshwar Pawati Kalinchok ACTED VDC/ Organisation Katakuti PI Ghyangsukathokar Jhule Hawa Municipality with completed/ongoing activities Japhe Laduk Caritas, CWV/RRN Babare ACTED Bhedpu Chyama Lakuridanda PI, RI/ANSAB Bhedpu Plan International Dandakharka Melung Malu Lamidanda ACTED Shahare Bhimeswor Concern Worldwide (CWV)/ Municipality RRN. IOM, Relief International Lapilang PI (RI)/ANSAB, UNDP Magapauwa PI Legend Bhirkot CWV/RRN Malu CWV/RRN # of completely damaged # of ongoing/completed public buildings activities by pillar Bhusaphedi Plan International (PI) Mirge CWV/RRN Boch PI, RI/ANSAB 21-28 1. Debris management Pawati PI Bulung Carita 11-20 2. Community infrastructure Phasku PI & livelihood 6-10 Chilangkha CWV/RRN Sailungeshwar PI 3. Restoration local services 3-5 Dandakharka PI Sundrawati PI Dodhapokhari PI 4% 1-2 Sunkhani PI Gairimudi CWV/RRN 12% Suspa Kshy- PI, RI/ANSAB Ghyangsu- PI amawati % of type of public buildngs 7% kathokar 14% Worang Caritas Hawa CWV/RRN Government building Planning Save the Children, Japhe CWV/RRN Government building Health facility UNDP/UNV Health facility School 79% Map Sources: Nepal Survey Department, Report on damaged government buildings, DoE, MoH, MoFALD and MoUD, 84% School August 2015. -

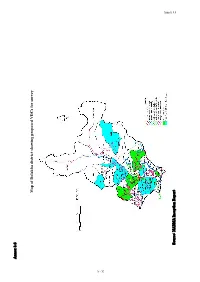

Map of Dolakha District Show Ing Proposed Vdcs for Survey

Annex 3.6 Annex 3.6 Map of Dolakha district showing proposed VDCs for survey Source: NARMA Inception Report A - 53 Annex 3.7 Annex 3.7 Summary of Periodic District Development Plans Outlay Districts Period Vision Objectives Priorities (Rs in 'ooo) Kavrepalanchok 2000/01- Protection of natural Qualitative change in social condition (i) Development of physical 7,021,441 2006/07 resources, health, of people in general and backward class infrastructure; education; (ii) Children education, agriculture (children, women, Dalit, neglected and and women; (iii) Agriculture; (iv) and tourism down trodden) and remote area people Natural heritage; (v) Health services; development in particular; Increase in agricultural (vi) Institutional development and and industrial production; Tourism and development management; (vii) infrastructure development; Proper Tourism; (viii) Industrial management and utilization of natural development; (ix) Development of resources. backward class and region; (x) Sports and culture Sindhuli Mahottari Ramechhap 2000/01 – Sustainable social, Integrated development in (i) Physical infrastructure (road, 2,131,888 2006/07 economic and socio-economic aspects; Overall electricity, communication), sustainable development of district by mobilizing alternative energy, residence and town development (Able, local resources; Development of human development, industry, mining and Prosperous and resources and information system; tourism; (ii) Education, culture and Civilized Capacity enhancement of local bodies sports; (III) Drinking