Editorial Board

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3702-NEP: Disaster Resilience of Schools Project and Title: DRSP/CLPIU/076/77-Kavre-02 Contract No

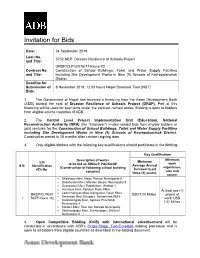

Invitation for Bids Date: 24 September 2019 Loan No. 3702-NEP: Disaster Resilience of Schools Project and Title: DRSP/CLPIU/076/77-Kavre-02 Contract No. Construction of School Buildings, Toilet and Water Supply Facilities and Title: including Site Development Works in Nine (9) Schools of Kavrepalanchok District Deadline for Submission of 8 November 2019, 12:00 hours Nepal Standard Time (NST) Bids: 1. The Government of Nepal has received a financing from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) toward the cost of Disaster Resilience of Schools Project (DRSP). Part of this financing will be used for payments under the contract named above. Bidding is open to bidders from eligible source countries of ADB. 2. The Central Level Project Implementation Unit (Education), National Reconstruction Authority (NRA) (the “Employer”) invites sealed bids from eligible bidders or joint ventures for the Construction of School Buildings, Toilet and Water Supply Facilities including Site Development Works in Nine (9) Schools of Kavrepalanchok District. Construction period is 18 months after contract signing date. 3. Only eligible bidders with the following key qualifications should participate in the bidding: Key Qualification Minimum Description of works Minimum Lot work to be bid as SINGLE PACKAGE Average Annual S.N. Identification experience, (Construction of following school building Turnover (Last (ID) No. size and complex) three (3) years). nature. • Bhaleswor Mavi, Malpi, Panauti Municipality-8 • Dedithumka Mavi, Mandan Deupur Municipality-9 • Gyaneswori Mavi, Padalichaur, Anaikot-1 • Himalaya Mavi, Pipalbot, Rosh RM-6 At least one (1) • Laxmi Narayan Mavi, Narayantar, Roshi RM-2 DRSP/CLPIU/0 USD 7.00 Million project of Saraswati Mavi, Bhugdeu, Bethanchok RM-6 1 76/77-Kavre -02 • worth USD • Sarbamangala Mavi, Aglekot, Panchkhal Municipality-3 2.52 Million. -

49215-001: Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project

Environmental Assessment Document Initial Environmental Examination Loan: 3260 July 2017 Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project: Panchkhal-Melamchi Road Project Main report-I Prepared by the Government of Nepal The Environmental Assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Government of Nepal Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport Department of Roads Project Directorate (ADB) Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project (EEAP) (ADB LOAN No. 3260-NEP) INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION OF PANCHKHAL - MELAMCHI ROAD JUNE 2017 Prepared by MMM Group Limited Canada in association with ITECO Nepal (P) Ltd, Total Management Services Nepal and Material Test Pvt Ltd. for Department of Roads, Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport for the Asian Development Bank. Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project (EEAP) ABBREVIATIONS AADT Average Annual Daily Traffic AC Asphalt Concrete ADB Asian Development Bank ADT Average Daily Traffic AP Affected People BOD Biological Oxygen Demand CBOs Community Based Organization CBS Central Bureau of Statistics CFUG Community Forest User Group CITIES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species CO Carbon Monoxide COI Corridor of Impact DBST Double Bituminous Surface Treatment DDC District Development Committee DFID Department for International Development, UK DG Diesel Generating DHM Department of Hydrology and Metrology DNPWC Department of National -

Community Diagnosis on Health Seeking Behavior and Social Problems in Bhaktapur and Kavrepalanchok Districts of Central Nepal

Original Research Article Journal of College of Medical Sciences-Nepal, Vol-13, No 3, July-Sept 017 ISSN: 2091-0657 (Print); 2091-0673 (Online) Open Access Community Diagnosis on Health Seeking Behavior and Social Problems in Bhaktapur and Kavrepalanchok Districts of central Nepal Pratibha Manandhar, Naresh Manandhar, Ram Krishna Chandyo, Sunil Kumar Joshi Department of Community Medicine, Kathmandu Medical College, Duwakot, Bhaktapur Correspondence ABSTRACT Dr. Pratibha Manandhar, Background & Objectives: The main objectives of this study were to Lecturer, assess the health status, health seeking behaviors and social problems of Department of Community Bhaktapur and Kavrepalanchok districts and also to learn the research Medicine, skills and establish relation with community for students. Materials & Kathmandu Medical College, Methods: This was a cross sectional study conducted by students of Duwakot, Bhaktapur second year MBBS for educational purposes of community diagnosis program (CDP) in one week period in nine VDC (village development Email: committee) of Bhaktapur district along with one VDC and one [email protected] municipality of Kavrepalanchok district. Household were selected based on convenient sampling method for the feasibility of students. Ethical DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3126/ clearance for the study was taken from Institutional Review Committee jcmsn.v13i3.17581 (IRC) of Kathmandu Medical College. Results: A total of 211and 105 households from Bhaktapur and Kavrepalanchok districts respectively Orcid ID: orcid.org/0000-0003- were included in this study . In Bhaktapur district, a slight female 2071-1347 predominance 549 (50.42 %) was observed, whereas in Kavrepalanchok th district male predominated marginally 270 (51.1%). In Bhaktapur Article received: June 24 2017 district, 35 (47.9%) were addicted to alcohol and smoking behaviors, Article accepted: Sept 26th 2017 whereas in Kavrepalanchok district it was 12 (29.3%). -

NHSSP Quarterly Report January 2020 to March 2020

NHSSP Quarterly Report January 2020 to March 2020 OFFICIAL Disclaimer This material has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. Recommended referencing: Nepal Health Sector Support Programme III – 2017 to 2020. PD – R4, Quarterly Report JANUARY 2020 – MARCH 2020 Kathmandu, Nepal OFFICIAL ABBREVIATIONS 2019-nCoV 2019 Novel Coronavirus ADB Asian Development Bank AM Aide Memoire ANC Antenatal Care ANM Auxiliary Nurse Midwife AS Additional Support AWPB Annual Work Plan and Budget BA Budget Analysis BC Birthing Centre BEONC Basic Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care BHS Basic Health Services BHSP Basic Health Services Package BoQ Bill of Quantity BPKIHS B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences CAPP Consolidated Annual Procurement Plan CB-IMCI Community-based Integrated Management of Childhood Illness CCMC Coronavirus Crisis Management Centre CEONC Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care CHD Child Health Division CMC Case Management Committee CMC-Nepal Centre for Mental Health and Counselling – Nepal COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease 2019 CS Caesarean Section CSD Curative Services Division CVICT Centre for Victims of Torture DDA Department of Drug Administration DFID UK Department for International Development DG Director-General DHIS2 District Health Information Software 2 DHO District Health Office DMT Decision-making Tool DoHS Department of Health Services DPR Detailed Project Report DUDBC Department of Urban Development and Building -

Nepal Earthquake: One Year On

ne year has passed since a devastating magnitude-7.8 earthquake struck Nepal on 25 April 2015, with the epicenter about 80 kilometers northwest of the capital, Kathmandu. This was the worst disaster to hit Nepal in decades. Only 17 days later a second earthquake of magnitude 7.4 hit near Mount Everest, taking more lives and destroying more homes. According to government estimates, the earthquakes EXECUTIVE Oleft over 750,000 houses and buildings destroyed or damaged and caused over 8,790 deaths. It is estimated that the earthquakes affected the lives of approximately eight million people, constituting almost one-third of the population of Nepal. With the situation dire, the Nepal government declared a state of emergency, and appealed for international aid. Along with other agencies, Habitat SUMMARY for Humanity answered the call to assist the people of Nepal. During the emergency phase, Habitat distributed 5,142 temporary shelter kits to families whose homes were destroyed or left uninhabitable. Habitat volunteers removed 650 tons of earthquake rubble, and distributed 20,000 water backpacks to families in earthquake-affected areas. As the emergency phase ended, Habitat’s programs shifted into reconstruction. Engineers completed safety assessments on 16,244 earthquake- damaged homes. Initial construction began on permanent homes in the community in Kavre district. As months passed, winter brought the threat of cold weather exposure, and Habitat distributed 2,424 winterization kits to families at risk to the elements. In addition, 32 trainers and 632 people in affected communities received instruction on the Participatory Approach for Safe Shelter Awareness. Overall in the first year since the earthquakes, Habitat for Humanity provided assistance to more than 43,700 families through various disaster response programs. -

Provincial Summary Report Province 3 GOVERNMENT of NEPAL

National Economic Census 2018 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 Provincial Summary Report Provincial National Planning Commission Province 3 Province Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 Published by: Central Bureau of Statistics Address: Ramshahpath, Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal. Phone: +977-1-4100524, 4245947 Fax: +977-1-4227720 P.O. Box No: 11031 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-9937-0-6360-9 Contents Page Map of Administrative Area in Nepal by Province and District……………….………1 Figures at a Glance......…………………………………….............................................3 Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Province and District....................5 Brief Outline of National Economic Census 2018 (NEC2018) of Nepal........................7 Concepts and Definitions of NEC2018...........................................................................11 Map of Administrative Area in Province 3 by District and Municipality…...................17 Table 1. Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Sex and Local Unit……19 Table 2. Number of Establishments by Size of Persons Engaged and Local Unit….….27 Table 3. Number of Establishments by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...34 Table 4. Number of Person Engaged by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...48 Table 5. Number of Establishments and Person Engaged by Whether Registered or not at any Ministries or Agencies and Local Unit……………..………..…62 Table 6. Number of establishments by Working Hours per Day and Local Unit……...69 Table 7. Number of Establishments by Year of Starting the Business and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...77 Table 8. -

Annual Report 2016

Action Works Nepal Annual Report 2016 Annual Report 2016 August 2015- July 2016 Action Works Nepal Thapathali, KabilMarga, House N0.37 Telephone: 00977- 01-4227730 Fax: 00977-4227730 GPO Box No 23336 Email: [email protected] www.actionworksnepal.com Action Works Nepal Annual Report 2016 Abbreviations: AWON Action Works Nepal NGO Non- governmental organization MCLC Miteri Children Learning Center MGDPA Miteri Ganga Devi Peace Award MRC Miteri Recycle Center MPLC Miteri Peace Learning Center MBC Miteri Birthing Center CDO Chief District Officer CBO Community Based Organization DPHO District Public Health Officer DDC District Development Committee GBV Gender Based Violence GBVIMS Gender Based Violence Information Management System ANM Auxiliary Nurse Midwife CAC Comprehensive Abortion Care MA Medical Abortion SMC School Management Committee VAW Violence against Women VDC Village Development Committee WHRD Women Human Rights Defenders SMC School Management Committee EC European Commission FP Family Planning SRHR Sexual and Reproductive Health Right SA Safe Abortion SAAF Safe Abortion Action Fund SRH Sexual Right Health Action Works Nepal Annual Report 2016 Introduction: Action Works Nepal (AWON) is a non-profit, non-governmental and independent organization. AWON started working informally since 2001 and was officially registered with District Administration Office Kathmandu in 2010. The focus is on political, economic, social, cultural, and environmental empowerment. From its inception, AWON has been involved in humanitarian and development activities in the remote mountain regions of Nepal. The major projects implemented in the past and at present focus on education, livelihoods, health, women empowerment, climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction and disaster relief and humanitarian works. -

(RTS) in the Unserved Vdcs of Far-Western, Mid-Western, Western and Central Developments Region Service Licensee (M/S Smart Telecom Pvt

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL RFP 02 F/Y 2066/67 Consultant for Monitoring and Evaluation of the Rural Telecommunications Service (RTS) in the unserved VDCs of Far-Western, Mid-Western, Western and Central Developments Region Service Licensee (M/S Smart Telecom Pvt. Ltd.) October 2009 2 Contents Request For Proposal …………………………………….1 Section 1 Letter of Invitation …………………………….3 Section 2 Instructions to the Consultants ………………….4 Data Sheet …………………………………… 17 Section 3 Technical Proposal Standard Forms ……………….21 Section 4 Financial Proposal Standard Forms ……………….31 Section 5 Terms of Reference ……………………………….. 44 Section 6 Contract for Consulting Services …………………..52 Section 7 Format of Bid Bond………………………………....71 Section 8 Format of Performance Guarentee…………………….72 3 Section 1. Letter of Invitation Nepal Telecommunications Authority Bluestar Office Complex, Tripureshwor, Kathmandu Dear Mr./Ms 1. Nepal Telecommunications Authority (NTA) invites proposals to provide the consulting services on Monitoring and Evaluation of the Rural Telecommunications Service (RTS) in the unserved VDCs of Far-Western, Mid-Western, Western and Central developments Regions of Nepal with the objective to supervise the implementation of the Roll out Obligation of the Licensee (M/S Smart Telecom Pvt. Ltd.). Details on the services are provided in the Terms of Reference . 2. A firm/consultant will be selected under Least Cost Selection (LCS) method and procedures described in this RFP 3. The RFP includes the following documents: Section 1 - Letter of Invitation Section 2 - Instructions to Consultants (including Data Sheet) Section 3 - Technical Proposal - Standard Forms Section 4 - Financial Proposal - Standard Forms Section 5 - Terms of Reference Section 6 - Standard Forms of Contract Section 7- Format of Bid Bond Section 8- Format of Performance Guarantee 4. -

Water and Sanitation in the City

Dhulikhel Municipality Office of the Municipal Executive Dhulikhel, Kavrepalanchok Presented By: Mr. Ashok Kumar Byanju Shrestha Water and Sanitation in the City Mayor Dhulikhel Municipality “Smart Sustainable City: a center of Health, Education, Tourism and Culture” Kavrepalanchok , District Nepal Environmental introduction of the city • 30 KM far east from Kathmandu • 1495 m above sea level • Most of the land is occupied by hilly areas • Average annual rainfall is 1300 mm • 70% of the total annual rainfall occurs in the rainy season( 3 months period) • Large water bodies are not available in the city Drinking Water Management in Dhulikhel: Histroy • Juddha Dhara (Tap) • Drinking Water Supply Project: collaboration with the Indian Embassy • Drinking Water Supply Project: Collaboration with German Embassy • Kavre Valley Integrated Drinking Water Project, which is currently under construction Kavre Valley Integrated Drinking Water Project • Project launched by three municipalities of Kavre district Dhulikhel, Banepa and Panauti to manage drinking water in an integrated manner. • operated by the Ministry of Physical Infrastructure in collaboration with the Asian Development Bank • 97% of the work has been completed Various efforts made by the Municipality regarding drinking water: • After the election (2074 BS), the elected people's representatives of Dhulikhel passed one house one tap policy from the first Municipal Assembly with the objective of providing healthy and adequate drinking water to every household in Dhulikhel • Under the policy, the Municipality made its plan in the first year to provide drinking water service so that every resident of Dhulikhel gets 65 liters of water per person per day. • The Municipality has adopted strategy to provide drinking water service in the areas not covered by the Kavre Valley Drinking Water Supply Project. -

Springs, Storage Towers, and Water Conservation in the Midhills of Nepal

ICIMOD Working Paper 2016/3 Springs, Storage Towers, and Water Conservation in the Midhills of Nepal Before After 1 About ICIMOD The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, ICIMOD, is a regional knowledge development and learning centre serving the eight regional member countries of the Hindu Kush Himalayas – Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan – and based in Kathmandu, Nepal. Globalization and climate change have an increasing influence on the stability of fragile mountain ecosystems and the livelihoods of mountain people. ICIMOD aims to assist mountain people to understand these changes, adapt to them, and make the most of new opportunities, while addressing upstream-downstream issues. We support regional transboundary programmes through partnership with regional partner institutions, facilitate the exchange of experience, and serve as a regional knowledge hub. We strengthen networking among regional and global centres of excellence. Overall, we are working to develop an economically and environmentally sound mountain ecosystem to improve the living standards of mountain populations and to sustain vital ecosystem services for the billions of people living downstream – now, and for the future. ICIMOD gratefully acknowledges the support of its core donors: The Governments of Afghanistan, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Norway, Pakistan, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. 2 ICIMOD Working Paper 2016/3 Springs, Storage Towers, and Water Conservation in the Midhills of Nepal Authors Binod Sharma, Santosh Nepal, Dipak Gyawali, Govinda Sharma Pokharel, Shahriar Wahid, Aditi Mukherji, Sushma Acharya, and Arun Bhakta Shrestha International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, June 2016 i Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal Copyright © 2016 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) All rights reserved. -

PRESS RELEASE Embassy of Japan P.O

PRESS RELEASE Embassy of Japan P.O. Box 264, Kathmandu JEINF No. 21-2018 February 28, 2018 Japanese Assistance for the Improvement of Agriculture and Marketing in Kavrepalanchok District (Kathmandu: 28th February): The Ambassador of Japan to Nepal, Mr. Masashi Ogawa, signed a grant contract for US$ 380,327.00 (approximately 39 million NRs.) with Ms. Maiko Kobayashi, Country Representative of AMDA Multisectoral and Integrated Development Services (AMDA-MINDS) for improvement of agricultural production and marketing in the earthquake-affected communities in Kavrepalanchok District. The support was made under the Grant Assistance for Japanese NGO Projects Scheme for FY 2017, and will be implemented by AMDA-MINDS, an international NGO based in Okayama, Japan. AMDA- MINDS will work with a local partner NGO, SAGUN. The grant assistance will be used for the project aiming at income generation among local people of Roshi Rural Municipality of Kavrepalanchok District who were severely affected by the earthquake of April 2015. This assistance is expected to accelerate rebuilding their daily lives. The project will implement the following activities: (1) provide local farmers with technical skills on the cultivation of high value crops, using less chemicals; (2) promote better access to water for daily use and agriculture with supporting construction of water supply systems, and (3) capacity building of Community Based Organizations (CBOs) for sustainable marketing and trading. This is the second year of a three-year project in Sipali-Chilaune and Walting, Ward Nos. 8 and 10 in the Roshi Rural Municipality. This stage in the project succeeds the previous stage which started from 2014 in Kharpachok, Ward No. -

Volume I - Main Report

Government of Nepal Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project Kupondole, Lalitpur Central Level Project Implementation Unit (CLPIU) Contract No. Survey, Design & Cost Estimate of Khopasi - Dhungkharka - Chyamrangbeshi - Milche - Borang Road in Kavre District (Ch 14+055- 18+591.8 Km) VOLUME I - MAIN REPORT June, 2017 Submitted by ERMC (P.) Ltd. (Environment & Resource Management Consultant) New Baneshwor, Kathmandu, Nepal P. O. Box: 12419, Kathmandu Tel.: 977-01-4483064, 4465863 Fax: 977-01-4479361 Email: [email protected], Website: www.ermcnepal.com Detail Engineering Survey and Design of Khopasi - Dhungkharka - Chyamrangbeshi - Milche - Borang Road (Kavre) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ERMC would like to extend special gratitude to all the concerned EEAP central Project coordination Unit and district team, officials of DDC, DTO and especially the local people of the project area who guided, advised, and cooperated ERMC and joined the survey team and guided/assisted during conduction of detailed engineering survey work. We also appreciate the contribution of all the individuals involved in this project works for their kind co-operation and help at every step of Detail Engineering Survey and Design of Khopasi - Dhungkharka - Chyamrangbeshi - Milche - Borang Road in Kavre District. Detail Engineering Survey and Design of Khopasi - Dhungkharka - Chyamrangbeshi - Milche - Borang Road (Kavre) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………… 1 1.1 RRSDP Districts for Implementation