Understanding the Role of Unpaid Care Work in Women's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

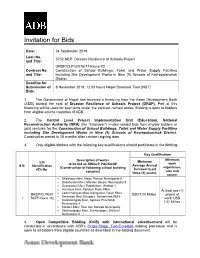

3702-NEP: Disaster Resilience of Schools Project and Title: DRSP/CLPIU/076/77-Kavre-02 Contract No

Invitation for Bids Date: 24 September 2019 Loan No. 3702-NEP: Disaster Resilience of Schools Project and Title: DRSP/CLPIU/076/77-Kavre-02 Contract No. Construction of School Buildings, Toilet and Water Supply Facilities and Title: including Site Development Works in Nine (9) Schools of Kavrepalanchok District Deadline for Submission of 8 November 2019, 12:00 hours Nepal Standard Time (NST) Bids: 1. The Government of Nepal has received a financing from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) toward the cost of Disaster Resilience of Schools Project (DRSP). Part of this financing will be used for payments under the contract named above. Bidding is open to bidders from eligible source countries of ADB. 2. The Central Level Project Implementation Unit (Education), National Reconstruction Authority (NRA) (the “Employer”) invites sealed bids from eligible bidders or joint ventures for the Construction of School Buildings, Toilet and Water Supply Facilities including Site Development Works in Nine (9) Schools of Kavrepalanchok District. Construction period is 18 months after contract signing date. 3. Only eligible bidders with the following key qualifications should participate in the bidding: Key Qualification Minimum Description of works Minimum Lot work to be bid as SINGLE PACKAGE Average Annual S.N. Identification experience, (Construction of following school building Turnover (Last (ID) No. size and complex) three (3) years). nature. • Bhaleswor Mavi, Malpi, Panauti Municipality-8 • Dedithumka Mavi, Mandan Deupur Municipality-9 • Gyaneswori Mavi, Padalichaur, Anaikot-1 • Himalaya Mavi, Pipalbot, Rosh RM-6 At least one (1) • Laxmi Narayan Mavi, Narayantar, Roshi RM-2 DRSP/CLPIU/0 USD 7.00 Million project of Saraswati Mavi, Bhugdeu, Bethanchok RM-6 1 76/77-Kavre -02 • worth USD • Sarbamangala Mavi, Aglekot, Panchkhal Municipality-3 2.52 Million. -

Editorial Board

Editorial Board Chief Editor Prof. Dr. Prem Sagar Chapagain Editors Dr. Ashok Pande Dr. Anila Jha Managing Editor Hemanta Dangal This views expressed in the articles are soley of the individual authors and do not nec- essarily reflect the views ofSocial Protection Civil Society Network-Nepal. © Social Protection Civil Society Network (SPCSN)-Nepal About the Journal With an objective to bring learnings, issues and voices on social protection through experts in regard to inform the social protection audiences, practitioners, stakeholders and actors as well as to suggest policymakers to adequately design social protection programs to fill the gaps and delivery transparency and accountability, Social Protection Civil Society Network (SPCSN) expects to publish the introductory issue of Journal of Social Protection in both print and online versions. Review Process This journal was published by Social Protection Civil Society Network (SPCSN) with supports of Save the Children Nepal Country Office in collaboration with Save the Children Finland & Ministry of Foreign Affairs Finland and with management supports from Children, Woman in Social Service and Human Rights (CWISH), Nepal. Editorial and Business Office Published by SPCSN Buddhanagar, Kathmandu Email: [email protected] Website: www.spcsnnepal.org Social Protection Civil Society Network (SPCSN) ISSN: ....................... Designed by: Krishna Subedi Printed at: .................... Journal of Social Protection, 2020 Volumn 1 December 2020 Contents Boosting the Impact of Nepal’s Child Grant through a Parenting Intervention ............................................................................................. 1-10 - Disa Sjöblom Social Protection in Health: Characteristics and Coverage of Health Insurance Program in Nepal ................................................... 11-26 - Geha Nath Khanal and Bhagawan Regmi Making Shock Responsive Social Protection System in Nepalese Context .................................................................................... -

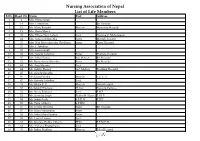

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

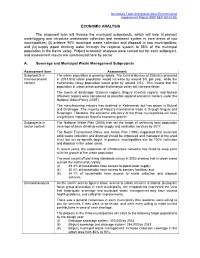

Economic Analysis

Secondary Towns Integrated Urban Environmental Improvement Project (RRP NEP 36188-02) ECONOMIC ANALYSIS The proposed loan will finance the municipal subprojects, which will help (i) prevent waterlogging and introduce wastewater collection and treatment system in core areas of two municipalities; (ii) achieve 90% municipal waste collection and disposal in two municipalities; and (iii) supply piped drinking water through the regional system to 85% of the municipal population in the Kavre valley. Project economic analyses were carried out for each subproject, and assessment results are summarized here by sector. A. Sewerage and Municipal Waste Management Subprojects Assessment Item Assessment Subprojects in The urban population is growing rapidly. The Central Bureau of Statistics projected macroeconomic in 2003 that urban population would increase by around 5% per year, while the context Kathmandu valley population would grow by around 2.5%. This means that the population in urban areas outside Kathmandu valley will increase faster. The towns of Biratnagar (Eastern region), Birgunj (Central region), and Butwal (Western region) were considered as possible regional economic centers under the National Urban Policy (2007). The manufacturing industry has declined in Kathmandu but has grown in Butwal and Biratnagar. The majority of Nepal’s international trade is through Birgunj and Biratnagar. Therefore, the economic efficiency of the three municipalities will have a significant impact on Nepal’s economic growth. Subprojects in The National Water Plan (2005) has set the target of achieving total population sector context coverage of basic drinking water supply and sanitation services by 2017. The Nepal Environment Policy and Action Plan (1993) suggested that municipal solid waste collection and disposal should be organized and managed at the ward level, but set no specific target. -

District Profile - Kavrepalanchok (As of 10 May 2017) HRRP

District Profile - Kavrepalanchok (as of 10 May 2017) HRRP This district profile outlines the current activities by partner organisations (POs) in post-earthquake recovery and reconstruction. It is based on 4W and secondary data collected from POs on their recent activities pertaining to housing sector. Further, it captures a wide range of planned, ongoing and completed activities within the HRRP framework. For additional information, please refer to the HRRP dashboard. FACTS AND FIGURES Population: 381,9371 75 VDCs and 5 municipalities Damage Status - Private Structures Type of housing walls Kavrepalanchok National Mud-bonded bricks/stone 82% 41% Cement-bonded bricks/stone 14% 29% Damage Grade (3-5) 77,963 Other 4% 30% Damage Grade (1-2) 20,056 % of households who own 91% 85% Total 98,0192 their housing unit (Census 2011)1 NEWS & UPDATES 1. A total of 1,900 beneficiaries as per District Technical Office (DTO/DLPIU) have received the Second Tranche in Kavre. 114 beneficiaries within the total were supported by Partner Organizations. 2. Lack of proper orientations to the government officials and limited coordination between DLPIU engineers and POs technical staffs are the major reconstruction issues raised in the district. A joint workshop with all the district authorities, local government authorities and technical persons was agreed upon as a probable solution in HRRP Coordination Meeting dated April 12, 2017. HRRP - Kavrepalanchok HRRP © PARTNERS SUMMARY AND HIGHLIGHTS3 Partner Organisation Implementing Partner(s) ADRA NA 2,110 ARSOW -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Comparison of Farm Production and Marketing Cost and Benefit Among Selected Vegetable Pockets in Nepal

The Journal of Agriculture and Environment Vol:11, Jun.2010 Technical Paper COMPARISON OF FARM PRODUCTION AND MARKETING COST AND BENEFIT AMONG SELECTED VEGETABLE POCKETS IN NEPAL Deepak Mani Pokhrel, PhD1 ABSTRACT In vein of exploring vegetable production and marketing related problems that could have hindered farmers from getting potential benefit, the study evaluates farm performances in selective vegetable pockets of Kabhrepalanchok, Sindhupalchok and Kaski districts. It describes farm strategies on pre and post harvest crop management, explores marketing channels and mechanisms of commodity transfer and price formation and assesses farm benefits of selective crops. Study method is based on exploration of processes and costs of production and marketing following observations and short interviews with local farmers in small groups, local traders in market centers and local informants. Marketing channels are explored, farm profits and shares on wholesale prices explained through cost-benefit assessments and prospects of vegetable production and marketing described. Key words: Cost-benefit, marketing-channel, Nepal, price-share, production-marketing system, vegetable pockets, mountain INTRODUCTION Nepalese agriculture has been confronting low return depriving farmers of their improvement in livelihood. Especially the mountain people who survive by cultivating cereals on mountain slopes, river basins and small valleys to meet their basic needs, due to poor income, frequently suffer from food-deficiency with low affordability for it. As a solution to which, and thereby to reduce farm-poverty, the country, through various plans and policies (NPC, 1995; NPC, 1998; NPC, 2003; NPC, 2007; MOAC, 2004; MOICS, 1992), identified 'vegetable' as one of the leading sub-sectors to harness advantages of agro- ecological diversities and has undertaken vegetable promotion strategy especially in the small holders visualizing comparative advantages of vegetable production and marketing in economic growth and development and thereby poverty reduction. -

49215-001: Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project

Environmental Assessment Document Initial Environmental Examination Loan: 3260 July 2017 Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project: Panchkhal-Melamchi Road Project Main report-I Prepared by the Government of Nepal The Environmental Assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Government of Nepal Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport Department of Roads Project Directorate (ADB) Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project (EEAP) (ADB LOAN No. 3260-NEP) INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION OF PANCHKHAL - MELAMCHI ROAD JUNE 2017 Prepared by MMM Group Limited Canada in association with ITECO Nepal (P) Ltd, Total Management Services Nepal and Material Test Pvt Ltd. for Department of Roads, Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport for the Asian Development Bank. Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project (EEAP) ABBREVIATIONS AADT Average Annual Daily Traffic AC Asphalt Concrete ADB Asian Development Bank ADT Average Daily Traffic AP Affected People BOD Biological Oxygen Demand CBOs Community Based Organization CBS Central Bureau of Statistics CFUG Community Forest User Group CITIES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species CO Carbon Monoxide COI Corridor of Impact DBST Double Bituminous Surface Treatment DDC District Development Committee DFID Department for International Development, UK DG Diesel Generating DHM Department of Hydrology and Metrology DNPWC Department of National -

Community Diagnosis on Health Seeking Behavior and Social Problems in Bhaktapur and Kavrepalanchok Districts of Central Nepal

Original Research Article Journal of College of Medical Sciences-Nepal, Vol-13, No 3, July-Sept 017 ISSN: 2091-0657 (Print); 2091-0673 (Online) Open Access Community Diagnosis on Health Seeking Behavior and Social Problems in Bhaktapur and Kavrepalanchok Districts of central Nepal Pratibha Manandhar, Naresh Manandhar, Ram Krishna Chandyo, Sunil Kumar Joshi Department of Community Medicine, Kathmandu Medical College, Duwakot, Bhaktapur Correspondence ABSTRACT Dr. Pratibha Manandhar, Background & Objectives: The main objectives of this study were to Lecturer, assess the health status, health seeking behaviors and social problems of Department of Community Bhaktapur and Kavrepalanchok districts and also to learn the research Medicine, skills and establish relation with community for students. Materials & Kathmandu Medical College, Methods: This was a cross sectional study conducted by students of Duwakot, Bhaktapur second year MBBS for educational purposes of community diagnosis program (CDP) in one week period in nine VDC (village development Email: committee) of Bhaktapur district along with one VDC and one [email protected] municipality of Kavrepalanchok district. Household were selected based on convenient sampling method for the feasibility of students. Ethical DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3126/ clearance for the study was taken from Institutional Review Committee jcmsn.v13i3.17581 (IRC) of Kathmandu Medical College. Results: A total of 211and 105 households from Bhaktapur and Kavrepalanchok districts respectively Orcid ID: orcid.org/0000-0003- were included in this study . In Bhaktapur district, a slight female 2071-1347 predominance 549 (50.42 %) was observed, whereas in Kavrepalanchok th district male predominated marginally 270 (51.1%). In Bhaktapur Article received: June 24 2017 district, 35 (47.9%) were addicted to alcohol and smoking behaviors, Article accepted: Sept 26th 2017 whereas in Kavrepalanchok district it was 12 (29.3%). -

Annual Report 2017

Published by ADRA Nepal The Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA) is a global humanitarian organization that works to bring long term development programs and emergency relief to the most vulnerable. Established in 1987, ADRA Nepal belongs to the worldwide ADRA network that aims to create just and positive impact in the lives of people living in poverty and distress. Content Coordination Communications Unit, ADRA Nepal Editor Shreeman Sharma Cover photo Children studying in Subarneshwor Basic School, Katunje, Bhaktapur peep into the classroom from window. Photo: Santosh K.C. The content of this publication can be reused for social cause. CONTENT Message from Country Director 04 Map of Nepal 05 Mission Vision and Identity 06 Our Impact Area 07 Responding Terai Flood 08 BURDAN 10 PRAGATI 12 PRIME/SURAKSHIT SAHAR 13 BRACED / ANUKULAN 14 United for Education 16 ADRA Connection 18 Disaster Resilence Education & Safe School (DRESS) 20 UNFPP & UNFPA Supported Activities 22 Enhancing Livelihood of Smallholder Farmers of Central 24 Terai Districts of Nepal (ELIVES) Food Security Enhancement and Agricultural Resilence 26 of Earthquake Affected Rural Nepalese Farmers (FOSTER) Agriculture Recovery of Earthquake Affected Families 28 in Dhading Districts (AREA) Good Governance and Livelihood (GOAL) 30 Expenditure 32 Our Reach 33 Acknowledgement 34 Team ADRA Nepal 35 Message from Country Director Time flies and 30 years have passed very quickly since tasks they were responsible for in order to bring about the day the Adventist Development and Relief Agency tangible outcomes. Financial and technical support (ADRA) started its efforts to improve people’s lives in from our donors and other stakeholders as well as the Nepal. -

NHSSP Quarterly Report January 2020 to March 2020

NHSSP Quarterly Report January 2020 to March 2020 OFFICIAL Disclaimer This material has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. Recommended referencing: Nepal Health Sector Support Programme III – 2017 to 2020. PD – R4, Quarterly Report JANUARY 2020 – MARCH 2020 Kathmandu, Nepal OFFICIAL ABBREVIATIONS 2019-nCoV 2019 Novel Coronavirus ADB Asian Development Bank AM Aide Memoire ANC Antenatal Care ANM Auxiliary Nurse Midwife AS Additional Support AWPB Annual Work Plan and Budget BA Budget Analysis BC Birthing Centre BEONC Basic Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care BHS Basic Health Services BHSP Basic Health Services Package BoQ Bill of Quantity BPKIHS B.P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences CAPP Consolidated Annual Procurement Plan CB-IMCI Community-based Integrated Management of Childhood Illness CCMC Coronavirus Crisis Management Centre CEONC Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care CHD Child Health Division CMC Case Management Committee CMC-Nepal Centre for Mental Health and Counselling – Nepal COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease 2019 CS Caesarean Section CSD Curative Services Division CVICT Centre for Victims of Torture DDA Department of Drug Administration DFID UK Department for International Development DG Director-General DHIS2 District Health Information Software 2 DHO District Health Office DMT Decision-making Tool DoHS Department of Health Services DPR Detailed Project Report DUDBC Department of Urban Development and Building -

VBST Short List

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C.