GRAPHITE Issue 1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confrontations with the Unconscious :: an Intensive Study of the Dreams of Women Learning Self-Defense. Deborah S

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1992 Confrontations with the unconscious :: an intensive study of the dreams of women learning self-defense. Deborah S. Stier University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Stier, Deborah S., "Confrontations with the unconscious :: an intensive study of the dreams of women learning self-defense." (1992). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2212. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2212 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFRONTATIONS WITH THE UNCONSCIOUS: AN INTENSIVE STUDY OF THE DREAMS OF WOMEN LEARNING SELF-DEFENSE A Thesis Presented by DEBORAH S. STIER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE February 1992 Psychology CONFRONTATIONS WITH THE UNCONSCIOUS: AN INTENSIVE STUDY OF THE DREAMS OF WOMEN LEARNING SELF-DEFENSE A Thesis Presented by DEBORAH S. STIER Approved as to style and content by: Murrayray M. Schwartz, ClVa ir Sally^fA. Freeman, Member Ronnie .i|»nof f-Bulman, Member D^avid M. Todd /^-Member C_jGharles'"E. CI if tc«1, Acting Chair Department of Psychology — — — DREAMS All night the dark buds of dreams open richly. In the center of every petal is a letter, and you imagine if you could only remember and string them all together they would spell the answer. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

An Ideological Analysis of the Birth of Chinese Indie Music

REPHRASING MAINSTREAM AND ALTERNATIVES: AN IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE BIRTH OF CHINESE INDIE MUSIC Menghan Liu A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill Esther Clinton © 2012 MENGHAN LIU All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis project focuses on the birth and dissemination of Chinese indie music. Who produces indie? What is the ideology behind it? How can they realize their idealistic goals? Who participates in the indie community? What are the relationships among mainstream popular music, rock music and indie music? In this thesis, I study the production, circulation, and reception of Chinese indie music, with special attention paid to class, aesthetics, and the influence of the internet and globalization. Borrowing Stuart Hall’s theory of encoding/decoding, I propose that Chinese indie music production encodes ideologies into music. Pierre Bourdieu has noted that an individual’s preference, namely, tastes, corresponds to the individual’s profession, his/her highest educational degree, and his/her father’s profession. Whether indie audiences are able to decode the ideology correctly and how they decode it can be analyzed through Bourdieu’s taste and distinction theory, especially because Chinese indie music fans tend to come from a community of very distinctive, 20-to-30-year-old petite-bourgeois city dwellers. Overall, the thesis aims to illustrate how indie exists in between the incompatible poles of mainstream Chinese popular music and Chinese rock music, rephrasing mainstream and alternatives by mixing them in itself. -

Copyright American Psychological Association. Not for Distribution

Copyright American Psychological Association. Not for distribution. Copyright American Psychological Association. Not for distribution. CONTENTS Acknowledgments ................................................................................... ix Introduction. The Neurocognitive Approach to Dreams ..................... 3 Chapter 1. Toward a Neurocognitive Model of Dreams .................. 9 Chapter 2. Methodological Issues in the Study of Dream Content .......................................................... 39 Chapter 3. The Hall–Van de Castle System .................................. 67 Chapter 4. A New Resource for Content Analysis ........................ 95 Chapter 5. New Ways to Study Meaning in Dreams ................... 107 Chapter 6. A Critique of Traditional Dream Theories ................ 135 References .............................................................................................. 171 Index ...................................................................................................... 197 About the Author ................................................................................. 209 vii Copyright American Psychological Association. Not for distribution. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to David Foulkes for two careful readings of the entire manu- script; to Adam Schneider for his superlative work in creating the tables and figures in the book; to Teenie Matlock and Raymond Gibbs, Jr., for their help in developing the ideas about figurative thinking in dreams; to Sarah Dunn, Heidi Block, and Melissa Bowen -

Modern Man in Search of a Soul

MODERN MAN IN SEARCH OF A SOUL Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com MODERN MAN IN SEARCH OF A SOUL BY C. G. JUNG ''l'S'YCJIOLOGJCAL 'tYJ>Bs'', ''TBB l'SYCROLOGY OJ' THIE UJl'COHSC'IOUS'' ''CONTJIIBUTIOJl'5 ro ANALYTICAL l"SYCROLOGY'', arc i! LONDON KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER e- CO LTD, BROADWAY HOUSE, 68-74 CARTER LANE, EC 1933 Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com Tramlt,ted by W. S. DELL AND CARY F. BAYNES Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com CONTENTS I. DREAM ANALYSIS IN ITS PRACTICAL APPLICATION II. PROBLBHS OF MODERN PsYCBOTBERAPY 32 Ill. AIMS OF PsYCBOTHERAPY 63 IV. A PsYcHOLOGICAL THEORY OF TYPES 85 V. Tim STAGES OF Lura 109 VI. FREUD AND JUNG-CONTRASTS l:J:2 VII. ARCHAIC MAN 143 VIII. PsYCHOLOGY AND LITERATURE 175 IX. THE BASIC POSTULATES OF ANALYTICAL PSYCHOLOGY 200 X. THE SPIRITUAL PROBLEM OF MODERN MAN 226 XJ PSYCHOTHERAPISTS OR THE CLERGY 255 Downloaded from https://www.holybooks.com TRANSLATORS' PREFACE WnBIN the last decade there have been many references from varied sources to the fact that the western world stands on the verge of a spiritual rebirth, that is, a funda. mental change of attitude toward the values of life After a long period of outward expansion, we are beginning to look within ourselves once more. There is very general agreement as to the phenomena surmundmg this increasing shift of interest from facts as such to their meaning and value to us as individuals, but as soon as we begin to analyse the anticipations nursed by the various groups in our world with respect to the change that is to be hoped for, agreement is at an end and a sharp confhct of forces makes itself felt. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

Album Top 1000 2021

2021 2020 ARTIEST ALBUM JAAR ? 9 Arc%c Monkeys Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not 2006 ? 12 Editors An end has a start 2007 ? 5 Metallica Metallica (The Black Album) 1991 ? 4 Muse Origin of Symmetry 2001 ? 2 Nirvana Nevermind 1992 ? 7 Oasis (What's the Story) Morning Glory? 1995 ? 1 Pearl Jam Ten 1992 ? 6 Queens Of The Stone Age Songs for the Deaf 2002 ? 3 Radiohead OK Computer 1997 ? 8 Rage Against The Machine Rage Against The Machine 1993 11 10 Green Day Dookie 1995 12 17 R.E.M. Automa%c for the People 1992 13 13 Linkin' Park Hybrid Theory 2001 14 19 Pink floyd Dark side of the moon 1973 15 11 System of a Down Toxicity 2001 16 15 Red Hot Chili Peppers Californica%on 2000 17 18 Smashing Pumpkins Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness 1995 18 28 U2 The Joshua Tree 1987 19 23 Rammstein Muaer 2001 20 22 Live Throwing Copper 1995 21 27 The Black Keys El Camino 2012 22 25 Soundgarden Superunknown 1994 23 26 Guns N' Roses Appe%te for Destruc%on 1989 24 20 Muse Black Holes and Revela%ons 2006 25 46 Alanis Morisseae Jagged Liale Pill 1996 26 21 Metallica Master of Puppets 1986 27 34 The Killers Hot Fuss 2004 28 16 Foo Fighters The Colour and the Shape 1997 29 14 Alice in Chains Dirt 1992 30 42 Arc%c Monkeys AM 2014 31 29 Tool Aenima 1996 32 32 Nirvana MTV Unplugged in New York 1994 33 31 Johan Pergola 2001 34 37 Joy Division Unknown Pleasures 1979 35 36 Green Day American idiot 2005 36 58 Arcade Fire Funeral 2005 37 43 Jeff Buckley Grace 1994 38 41 Eddie Vedder Into the Wild 2007 39 54 Audioslave Audioslave 2002 40 35 The Beatles Sgt. -

Appelons Un Chart, Un Chart - Semaine 39, 2016

Appelons un chart, un chart - Semaine 39, 2016 Charts Français (SNEP) Classement Artiste Album Date de sortie Tendance actuel 8 Bruce Springsteen Chapter & Verse 23/09/2016 Entrée 15 Airbourne Breakin’ Outta Hell 23/09/2016 Entrée 18 Marillion F.E.A.R. 23/09/2016 Entrée 37 La Femme Mystère 16/09/2016 -16 Nick Cave & The 39 Skeleton Tree 09/09/2016 -19 Bad Seeds Red Hot Chili 64 The Getaway 16/06/2016 -4 Peppers Live At The Greek 65 Joe Bonamassa 23/09/2016 Entrée Theatre Acoustic Recordings - 76 Jack White 09/09/2016 -24 1998 - 2016 86 Radiohead A Moon Shaped Pool 08/05/2016 -12 91 The Clash London Calling 14/12/1979 Retour 102 Ghost Popestar (EP) 16/09/2016 -62 111 Ghost Meliora 21/08/2015 +16 Young As The 113 Passenger Morning Old As 23/09/2016 Entrée The Sea 128 Warpaint Heads Up 23/09/2016 Entrée Nevermind The 134 Sex Pistols Bollocks, Here’s The 27/10/1977 Retour Sex Pistols 138 Kansas The Prelude Implicit 23/09/2016 Entrée Ben Harper & The 149 Call It What It Is 08/04/2016 -14 Innocent Criminals 164 Michael Kiwanuka Love & Hate 15/07/2016 -17 167 Jeff Buckley Grace 23/08/1994 Retour 176 Insomnium Winter's Gate 23/09/2016 Entrée 184 Muse Drones 08/06/2015 -25 Ici Le Jour (A Tout 185 Feu Chatterton! 16/11/2015 -17 Ensevli) Charts Anglais (Official Charts) Classement Artiste Album Date de sortie Tendance actuel Young As The 1 Passenger Morning Old As 23/09/2016 Entrée The Sea 2 Bruce Springsteen Chapter & Verse 23/09/2016 Entrée 4 Marillion F.E.A.R. -

Dominican Republic Jazz Festival @ 20

NOVEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

The Psychological Concepts in Taylor Swift's "Blank Space"

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL CONCEPTS IN TAYLOR SWIFT'S "BLANK SPACE" A FINAL PROJECT In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement For S-1 Degree in American Cultural Studies In English Department, Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University Submitted by: Novia Putri Anindhita 13020111130073 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DIPONEGORO UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2015 x PRONOUNCEMENT I state truthfully that this project is compiled by me without taking the results from other research in any university, in S-1, S-2, and S-3 degree and diploma. In addition, I ascertain that I do not take the material from other publications or someone’s work except for the references mentioned in the bibliography. Semarang, 9 February 2016 Novia Putri Anindhita ii APPROVAL Approved by Advisor, Retno Wulandari, S.S, M.A. NIP. 19750525 200501 2 002 iii VALIDATION Approved by Strata I Final Project Examination Committee Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University on March 2016 Chair Person First Member Arido Laksono, S.S, M.Hum. Dra. Christine Resnitriwati, M.Hum. NIP. 19750711 199903 1 002 NIP.19560216 198303 2 001 Second Member Third Member Sukarni Suryaningsih, S.S., M.Hum Drs. Mualimin, M.Hum. NIP. 19721223 199802 2 001 NIP. 19611110 198710 1 001 iv MOTTO AND DEDICATION Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance, you must keep moving (Albert Enstein). You’re lucky enough to be different, never change (Taylor Swift). This final project is dedicated to my beloved parents. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Praise be to Allah, who has given strength and spirit to this final project on “The Psychological Concepts in Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space”” came to a completion. -

October 19-25, 2017 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFTWAYNE • What’S Happening at Sweetwater? Artist Events, Workshops, Camps, and More!

OCTOBER 19-25, 2017 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFTWAYNE • WWW.WHATZUP.COM What’s happening at Sweetwater? Artist events, workshops, camps, and more! FREE Pro Tools Master Class OPEN MIC Roll up your sleeves and get hands-on as you learn from Pro Tools expert, and NIGHT professional recording engineer, Nathan Heironimus, right here at Sweetwater. 7–8:30PM every third Monday of the month November 9–11 | 9AM–6PM $995 per person This is a free, family-friendly, all ages event. Bring your acoustic instruments, your voice, and plenty of friends to Sweetwater’s Crescendo Club stage for a great night of local music and entertainment. Buy. Sell. Trade. Play. FREE Have some old gear and looking to upgrade? Bring it in to Sweetwater’s Gear Exchange and get 5–8PM every second and your hands on great gear and incredible prices! fourth Tuesday of the month FREE Hurry in, items move fast! Guitars • Pedals • Amps • Keyboards & More* 7–8:30PM every last Check out Gear Exchange, just inside Sweetwater. Thursday of the month DRUM CIRCLE FREE 7–8PM every first Tuesday of the month *While supplies last Don’t miss any of these events! Check out Sweetwater.com/Events to learn more and to register! Music Store Community Events Music Lessons Sweetwater.com • (260) 432-8176 • 5501 US Hwy 30 W • Fort Wayne, IN 2 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- www.whatzup.com ------------------------------------------------------------October 19, 2017 whatzup Volume 22, Number 12 s local kids from 8 to 80 gear up for the coming weekend’s big Fright Night activi- ties, there’s much to see and do in and around the Fort Wayne area that has noth- ing at all to do with spooks and goblins and ghouls and jack-o-lanterns. -

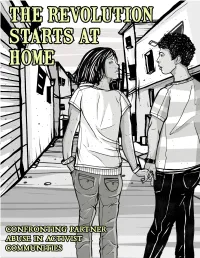

Confronting Partner Abuse in Activist Communities

Confronting Partner Abuse in Activist Communities 1 The Revolution Starts at Home I am not proposing that sexual violence and domestic violence will no longer ex- ist. I am proposing that we create a world where so many people are walking around with the skills and knowledge to support someone that there is no longer a need for anonymous hotlines. I am proposing that we break through the shame of survivors (a result of rape cul- ture) and the victim-blaming ideology of all of us (also a result of rape culture), so that survivors can gain support from the people already in their lives. I am propos- ing that we create a society where com- munity members care enough to hold an abuser accountable so that a survivor does not have to flee their home. I am proposing that all of the folks that have been disap- pointed by systems work together to create alternative systems. I am proposing that we organize. Rebecca Farr, CARA member 2 Confronting Partner Abuse in Activist Communities contents Where the revolution started: an introduction 5 Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha Introduction 9 Ching-In Chen The revolution starts at home: pushing through the fear 10 Jai Dulani There is another way 15 Ana Lara How I learned to stop worrying and love the wreckage 21 Gina de Vries Infestation 24 Jill Aguado, Anida Ali, Kay Barrett, Sarwat Rumi, of Mango Tribe No title 30 Anonymous I married a marxist monster 33 Ziggy Ponting Philly’s pissed and beyond 38 Timothy Colman Notes on partner consent 44 Bran Fenner Femora and fury: on IPV and disability 48 Peggy