Haier Electronics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Korea Tech Strategy

November 13, 2012 The Age of Transition Korea Tech Strategy The outlook for IT from a “disruptive innovation” perspective Daewoo Securities Co., Ltd. James Song +822-768-3722 Mobile revolution: From revolution to evolution [email protected] The mobile revolution has been a history of „disruptive innovation.‰ And at the heart of Wonjae Park this remarkable shake-up lie Apple, Samsung Electronics (SEC), Google, and Amazon. +822-768-3372 Notably, the global IT industry is currently facing several major shifts and issues, [email protected] including: 1) AppleÊs „innovatorÊs dilemma‰; 2) a reshuffling of global supply chains; 3) Jonathan Hwang the return of Microsoft; and 4) the zero growth of the PC industry. How Korean IT +822-768-4140 players approach these issues will create significant implications for the memory, [email protected] display, components, and electronic materialsÊ markets in 2013 onwards. Will Cho “Apple without SEC” vs. “SEC without Apple” +822-768-4306 [email protected] Apple is now one of the most valuable corporations in the world. However, SEC sells Young Ryu more smartphones than Apple does. Unsurprisingly, global investors are paying keen +822-768-4138 attention to the competition between Apple and SEC, their innovations, and their [email protected] potential breakup. Our analysis suggests Apple is increasingly leaning toward „sustaining innovation‰ while SEC pursues a strategy of differentiation. At the same Brian Oh time, in reshuffling the global supply chain, we expect Apple could have difficulty +822-768-4135 [email protected] procuring parts supply without SECÊs contributions, while the Korean giant is likely to see very limited impacts from the absence of demand from Apple. -

Home Appliance Cautious Buy

Sector Research | China Home Appliance THIS IS THE TRANSLATION OF A REPORT ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN CHINESE BY GUOSEN SECURITIES CO., LTD ON SEPTEMBER 24, 2012 October 16, 2012 Home Appliance Cautious Buy Cherry pick home-appliance names amid the price corrections Investment highlights Analyst Wang Nianchun We expect home-appliance y-o-y sales volume growth to rebound moderately +755-82130407 in 4Q 2012. Based on our channel checks and data already released for Jul-Aug [email protected] S0980510120027 2012, 3Q sales volume of various sub-sectors was in line with expectations, and the profitability of the TV sub-sector slightly beat expectations. The subsidies for energy efficient home-appliance products introduced in June are unlikely to materially boost sales until three to six months after their launch. We expect the 4Q y-o-y sales Sales Contact volume growth of air conditioners, refrigerators, washing machines and LCD TVs will be 7.5%, 5.8%, 5.0% and 0.8% respectively, representing a modest rebound from the Roger Chiman Managing Director first three quarters. +852 2248 3598 [email protected] Divergence within the sector intensifies, and we suggest waiting for buying Chris Berney opportunities amid price pullbacks. The overall industry sentiment has been tepid Managing Director +852 2248 3568 since the beginning of 2012, but product-mix upgrade and lower material costs could lead [email protected] to an improvement in profitability this year. Based on our estimates, subsidy policies for Andrew Collier energy efficient home-appliance products will have more significant effects in 2013 than Director +852 2248 3528 this year. -

China Equity Strategy

June 5, 2019 09:40 AM GMT MORGAN STANLEY ASIA LIMITED+ China Equity Strategy | Asia Pacific Jonathan F Garner EQUITY STRATEGIST [email protected] +852 2848-7288 The Rubio "Equitable Act" - Our Laura Wang EQUITY STRATEGIST [email protected] +852 2848-6853 First Thoughts Corey Ng, CFA EQUITY STRATEGIST [email protected] +852 2848-5523 Fran Chen, CFA A new bill sponsored by US Senator Marco Rubio has the EQUITY STRATEGIST potential to cause significant change in the listing domains of [email protected] +852 2848-7135 Chinese firms. After the market close in the US yesterday 4th June the Wall Street Journal published an Op-Ed by US Senator Marco Rubio in which he announced that he intends to sponsor the “Equitable Act” – an acronym for Ensuring Quality Information and Transparency for Abroad-Based Listings on our Exchanges. At this time the text of the bill has not been published and we are seeking additional information about its contents and likelihood of passing. However, our early reaction is that this has the potential to cause significant changes in the domain for listings of Chinese firms going forward with the potential for de- listing of Chinese firms on US exchanges and re-listing elsewhere (most likely Hong Kong). More generally we see this development as part of an increased escalation of tensions between China and the US on multiple fronts which should cap the valuation multiple for China equities, in particular in the offshore index constituents and US-listed parts of the universe. We provide a list of the potentially impacted China / HK names with either primary or secondary listings on Amex, NYSE or Nasdaq. -

Datta, Hannes; Van Heerde, H.J.; Dekimpe, Marnik; Steenkamp, J.E.B.M

Tilburg University Cross-National Differences in Market Response: Line-Length, Price, and Distribution Elasticities in Fourteen Indo-Pacific Rim Economies Datta, Hannes; van Heerde, H.J.; Dekimpe, Marnik; Steenkamp, J.E.B.M. Publication date: 2019 Document Version Early version, also known as pre-print Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Datta, H., van Heerde, H. J., Dekimpe, M., & Steenkamp, J. E. B. M. (2019). Cross-National Differences in Market Response: Line-Length, Price, and Distribution Elasticities in Fourteen Indo-Pacific Rim Economies. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. okt. 2021 Universality or Differences in Marketing Elasticities in Emerging versus Developed Markets? The Moderating Role of Brand Equity Hannes Datta Harald J. van Heerde Marnik G. Dekimpe Jan-Benedict E.M. Steenkamp This version: September 13, 2019 Hannes Datta is Associate Professor of Marketing at Tilburg University (e-mail: [email protected]). -

TCL MULTIMEDIA TECHNOLOGY HOLDINGS LIMITED TCL 多媒體科技控股有限公司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 01070)

THIS DOCUMENT AND THE ACCOMPANYING DOCUMENTS (IF ANY) ARE IMPORTANT AND REQUIRE YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt as to any aspect of this Prospectus or as to the action to be taken, you should consult your stockbroker or other licensed securities dealer, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional adviser. If you have sold or transferred all your Shares, you should at once hand the Prospectus Documents to the purchaser(s) or the transferee(s) or to the bank, the licensed securities dealer or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser(s) or transferee(s). A copy of each of the Prospectus Documents, together with a copy of the documents specified in the section headed “Documents delivered to the Registrar of Companies” in Appendix III to this Prospectus, has been registered with the Registrar of Companies in Hong Kong as required by Section 342C of the Companies (Winding Up and Miscellaneous Provisions) Ordinance. The Registrar of Companies in Hong Kong, the Stock Exchange and the SFC take no responsibility as to the contents of any of these documents. You should read the whole of this Prospectus including the discussions of certain risks and other factors as set out in the section headed “WARNING OF THE RISKS OF DEALING IN SHARES AND NIL PAID RIGHTS” of this Prospectus. Subject to the granting of approval for the listing of, and permission to deal in, the Rights Shares in both nil-paid and fully-paid forms on the Stock Exchange as well as compliance with the stock admission requirements of HKSCC, the Rights Shares in both nil-paid and fully-paid forms will be accepted as eligible securities by HKSCC for deposit, clearance and settlement in CCASS with effect from the respective commencement dates of dealings in the Rights Shares in their nil-paid and fully-paid forms on the Stock Exchange. -

Phase Exhibitior Section Stand Number 1 SASSIN INTERNATIONAL ELECTRIC SHANGHAI CO.,LTD

VIP Exhibitors of the 114th Session of Canton Fair Phase Exhibitior Section Stand Number 1 SASSIN INTERNATIONAL ELECTRIC SHANGHAI CO.,LTD. Electronic and Electrical Products 5.1A09-22 1 SICHUAN JIUZHOU ELECTRIC GROUP CO., LTD. Consumer Electronics 11.3C35-46 1 Guangzhou Midea Hualing Refrigerator Co., Ltd. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2A77-92 1 GREE ELECTRIC APPLIANCES,INC.OF ZHUHAI Household Electrical Appliances 4.2A51-78 1 MIDEA GROUP CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2A09-60 1 HAIER GROUP Household Electrical Appliances 3.2B01-54 1 GUANGDONG XINBAO APPLIANCES HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 4.2F31-47 1 NO.168 HUANCHENG EAST RD.ZHOUXIANG CIXI,NINGBO P.R.C. Household Electrical Appliances 4.2F19-30 1 NINGBO AUX IMP.& EXP CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 4.2D13-46 1 XINGXING GROUP CO.,LTD Household Electrical Appliances 4.2I07-21 1 TCL CORPORATION Household Electrical Appliances 3.2G41-60 1 GUANGDONG GALANZ ENTERPRISE CO., LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 4.2A06-45 1 Guangzhou Wanbao Group Co.,Ltd. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2E50-67 1 GUANGDONG CHIGO AIR CONDITIONING CO.LTD Household Electrical Appliances 4.2D51-71 1 Homa Appliances Co., Ltd Household Electrical Appliances 3.2C01-12 1 NINGBO KAIBO GROUP CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 2.2D37-42,2.2E07-12 1 NINGBO XINLE HOUSEHOLD APPLIANCES CO., LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2C85-96 1 SICHUAN CHANGHONG ELECTRIC CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2E20-35 1 NINGBO LAMO ELECTRIC APPLIANCE CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2G29-40 1 HEFEI MEILING COMPANY LIMITED Household Electrical Appliances 3.2E36-49 1 CUORI ELECTRICAL APPLICANAES GROUP CO.,LTD. -

Industrial Policy and Global Value Chains: the Experience of Guangdong, China and Malaysia in the Electronics Industry

Industrial Policy and Global Value Chains: The experience of Guangdong, China and Malaysia in the Electronics Industry By VASILIKI MAVROEIDI Clara Hall College This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Centre of Development Studies, University of Cambridge Date of Submission: September, 2018 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. 2 Acknowledgments This thesis would have been impossible without the support and encouragement of a great many people that I met during this journey. My biggest thanks go to Dr. Ha-Joon Chang. He believed in me since the very first time we met and all our conversations since (together with the copious amount of red ink spent on my earlier drafts) have pushed me to think harder and improve not only as a scholar, but also as a person. -

Hisense Kelon Electrical Holdings Company Limited 海信科龍電器股份有限公司

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. HISENSE KELON ELECTRICAL HOLDINGS COMPANY LIMITED 海信科龍電器股份有限公司 (A joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 00921) DISCLOSEABLE TRANSACTIONS SUBSCRIPTION OF WEALTH MANAGEMENT PRODUCTS Reference is made to the announcements of the Company dated 1 September 2016 and 7 September 2016 in respect of the August Wealth Management Agreement, the First September Wealth Management Agreement and the Second September Wealth Management Agreement, pursuant to which Hisense Refrigerator (as subscriber) subscribed for the wealth management products in the aggregate subscription amount of RMB900,000,000 (equivalent to approximately HK$1,045,504,145Note 1) from the Agricultural Bank of China (as issuer). The Board is pleased to announce that apart from the August Wealth Management Agreement, the First September Wealth Management Agreement and the Second September Wealth Management Agreement, on 26 September 2016, Hisense Refrigerator entered into the Third September Wealth Management Agreement with the Agricultural Bank of China to subscribe for the 75-day Wealth Management Product in the subscription amount of RMB200,000,000 (equivalent to approximately HK$232,660,943Note 2). The Third September Wealth Management Agreement by itself does not constitute discloseable transaction of the Company under Rule 14.06 of the Listing Rules. -

China's March on the 21St Century

China’s March on the 21st Century A Report of the Aspen Strategy Group Kurt M. Campbell, Editor Willow Darsie, Editor u Co-Chairmen Joseph S. Nye, Jr. Brent Scowcroft To obtain additional copies of this report, please contact: The Aspen Institute Fulfillment Office P.O. Box 222 109 Houghton Lab Lane Queenstown, Maryland 21658 Phone: (410) 820-5338 Fax: (410) 827-9174 E-mail: [email protected] For all other inquiries, please contact: The Aspen Institute Aspen Strategy Group Suite 700 One Dupont Circle, NW Washington, DC 20036 Phone: (202) 736-5800 Fax: (202) 467-0790 Copyright © 2007 The Aspen Institute Published in the United States of America 2007 by The Aspen Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 0-89843-471-8 Inv No.: 07-007 CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . v DISCUSSANTS AND GUEST EXPERTS . 1 WORKSHOP AGENDA. 5 SCENE SETTER AND DISCUSSION GUIDE Kurt M. Campbell . 13 THE CHINESE ECONOMY:MAKING STRIDES,GOING GLOBAL Dominic Barton and Jonathan Woetzel Dragon at the Crossroads: The Future of China’s Economy . 25 Lael Brainard Adjusting to China’s Rise . 37 ENERGY, THE ENVIRONMENT, AND OTHER TRANSNATIONAL CHALLENGES John Deutch, Peter Ogden, and John Podesta China’s Energy Challenge . 53 Margaret A. Hamburg Public Health and China: Emerging Disease and Challenges to Health . 61 OF SOFT POWER AND CHINA’S PEACEFUL RISE Zha Jianying Popular Culture in China Today . 77 Wang Jisi What China Needs in the World and from the United States. 85 STRATEGIC COMPETITION,REGIONAL REACTIONS, AND GLOBAL GAMBITS Michael J. Green Meet the Neighbors: Regional Responses to China’s Rise . -

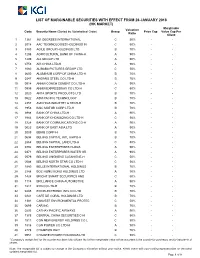

HK Marginable List

LIST OF MARGINABLE SECURITIES WITH EFFECT FROM 26 JANUARY 2018 (HK MARKET) Marginable Valuation Code Security Name (Sorted by Alphabetical Order) Group Price Cap Value Cap Per Ratio Client 1 1361 361 DEGREES INTERNATIONAL C 50% - - 2 2018 AAC TECHNOLOGIES HOLDINGS IN C 50% - - 3 3383 AGILE GROUP HOLDINGS LTD B 70% - - 4 1288 AGRICULTURAL BANK OF CHINA-H A 90% - - 5 1299 AIA GROUP LTD A 90% - - 6 0753 AIR CHINA LTD-H A 90% - - 7 1060 ALIBABA PICTURES GROUP LTD C 50% - - 8 2600 ALUMINUM CORP OF CHINA LTD-H B 70% - - 9 0347 ANGANG STEEL CO LTD-H B 70% - - 10 0914 ANHUI CONCH CEMENT CO LTD-H A 90% - - 11 0995 ANHUI EXPRESSWAY CO LTD-H C 50% - - 12 2020 ANTA SPORTS PRODUCTS LTD B 70% - - 13 0522 ASM PACIFIC TECHNOLOGY B 70% - - 14 2357 AVICHINA INDUSTRY & TECH-H B 70% - - 15 1958 BAIC MOTOR CORP LTD-H B 70% - - 16 3988 BANK OF CHINA LTD-H A 90% - - 17 1963 BANK OF CHONGQING CO LTD-H C 50% - - 18 3328 BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS CO-H A 90% - - 19 0023 BANK OF EAST ASIA LTD A 90% - - 20 2009 BBMG CORP-H B 70% - - 21 0694 BEIJING CAPITAL INTL AIRPO-H B 70% - - 22 2868 BEIJING CAPITAL LAND LTD-H C 50% - - 23 0392 BEIJING ENTERPRISES HLDGS A 90% - - 24 0371 BEIJING ENTERPRISES WATER GR A 90% - - 25 0579 BEIJING JINGNENG CLEAN ENE-H C 50% - - 26 0588 BEIJING NORTH STAR CO LTD-H C 50% - - 27 1880 BELLE INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS B 70% - - 28 2388 BOC HONG KONG HOLDINGS LTD A 90% - - 29 1428 BRIGHT SMART SECURITIES AND C 50% - - 30 1114 BRILLIANCE CHINA AUTOMOTIVE A 90% - - 31 1211 BYD CO LTD-H B 70% - - 32 0285 BYD ELECTRONIC INTL CO LTD B 70% - - 33 0341 CAFE DE CORAL HOLDINGS LTD B 70% - - 34 1381 CANVEST ENVIRONMENTAL PROTEC C 50% - - 35 0699 CAR INC B 70% - - 36 0293 CATHAY PACIFIC AIRWAYS A 90% - - 37 1375 CENTRAL CHINA SECURITIES C-H C 50% - - 38 1811 CGN NEW ENERGY HOLDINGS CO L C 50% - - 39 1816 CGN POWER CO LTD-H A 90% - - 40 2778 CHAMPION REIT B 70% - - 41 0951 CHAOWEI POWER HOLDINGS LTD C 50% - - * Company's margin limit for the counter has been fully utilized. -

Emerging Best Practices of Chinese Globalizers the Corporate Global Citizenship Challenge

Industry Agenda Emerging Best Practices of Chinese Globalizers The Corporate Global Citizenship Challenge In collaboration with The Boston Consulting Group © World Economic Forum 2012 - All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system. Contents Preface 3 Preface The 42nd Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum was held under the theme The Great Transformation: Shaping New Models 5 Executive Summary in January 2012. Leaders from business, government, international organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) expressed 7 Part I The Economic Contribution of their aspirations and exchanged innovative ideas on how we can Chinese Globalizers and Early Challenges create new global models needed for the inevitable transformation upon us. Given that China has been going through major changes 10 Part II The Development of Corporate in the past three decades, this journey is one that is already rather Global Citizenship among Chinese familiar. In every corner of this vast nation, transformations have Companies over the Past Decade time and again improved people’s lives, from remote rural regions to 10 2001-2005: Re-introduction after modern urban cities, from traditional media to social networks, from joining WTO private companies to state-owned enterprises. 11 2006-2007: Evolution of the Robert Greenhill China’s impact on the world economy is increasing constantly, corporate citizenship concept Managing Director through a greater global presence of Chinese companies in international markets. At the domestic level, the concept of corporate and Chief Business 11 2008-present: Accelerated responsibility is often well understood. -

Post Print This Article Is a Version After Peer-Review, with Revisions Having Been Made

Post Print This article is a version after peer-review, with revisions having been made. In terms of appearance only this might not be the same as the published article. THE GLOBALISATION OF CHINESE BRANDS Marketing Intelligence &Planning, (2006) 24:4, 365-379 Ying Fan Brunel Business School Brunel University Uxbridge, Middlesex UB8 3PH England [email protected] Keywords branding, Chinese brands, internationalisation, international marketing global markets, globalisation THE GLOBALISATION OF CHINESE BRANDS Abstract China has taken over Japan over the last decade to become the largest manufacturer and exporter of more than one hundred consumer products. However, China, as “the world factory”, has yet to create a single brand that is recognised worldwide. The recent acquisition of IBM’s PC business by China’s Lenovo may signal the beginning of the globalisation of Chinese brands. This paper considers the current brand revolution in China, focusing on the unique challenge faced by major Chinese enterprises: how to sustain their brands in domestic competition and how to expand in the global markets. The paper is divided into two parts: it first gives a brief review of the development of marketing and branding in China since the start of economic reform in 1978, and then discusses current issues in the domestic market: changes from price competition to brand competition, as well as diversification and the role of the government. The second part examines the routes to internationalisation taken by some of China’s biggest brands; differences in their entry modes and branding strategies are analysed. Introduction It is now difficult to find a shop in the West that does not sell products with a Made- in-China label.