1 the Internationalization of Emerging Market Multinationals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home Appliance Cautious Buy

Sector Research | China Home Appliance THIS IS THE TRANSLATION OF A REPORT ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN CHINESE BY GUOSEN SECURITIES CO., LTD ON SEPTEMBER 24, 2012 October 16, 2012 Home Appliance Cautious Buy Cherry pick home-appliance names amid the price corrections Investment highlights Analyst Wang Nianchun We expect home-appliance y-o-y sales volume growth to rebound moderately +755-82130407 in 4Q 2012. Based on our channel checks and data already released for Jul-Aug [email protected] S0980510120027 2012, 3Q sales volume of various sub-sectors was in line with expectations, and the profitability of the TV sub-sector slightly beat expectations. The subsidies for energy efficient home-appliance products introduced in June are unlikely to materially boost sales until three to six months after their launch. We expect the 4Q y-o-y sales Sales Contact volume growth of air conditioners, refrigerators, washing machines and LCD TVs will be 7.5%, 5.8%, 5.0% and 0.8% respectively, representing a modest rebound from the Roger Chiman Managing Director first three quarters. +852 2248 3598 [email protected] Divergence within the sector intensifies, and we suggest waiting for buying Chris Berney opportunities amid price pullbacks. The overall industry sentiment has been tepid Managing Director +852 2248 3568 since the beginning of 2012, but product-mix upgrade and lower material costs could lead [email protected] to an improvement in profitability this year. Based on our estimates, subsidy policies for Andrew Collier energy efficient home-appliance products will have more significant effects in 2013 than Director +852 2248 3528 this year. -

China Equity Strategy

June 5, 2019 09:40 AM GMT MORGAN STANLEY ASIA LIMITED+ China Equity Strategy | Asia Pacific Jonathan F Garner EQUITY STRATEGIST [email protected] +852 2848-7288 The Rubio "Equitable Act" - Our Laura Wang EQUITY STRATEGIST [email protected] +852 2848-6853 First Thoughts Corey Ng, CFA EQUITY STRATEGIST [email protected] +852 2848-5523 Fran Chen, CFA A new bill sponsored by US Senator Marco Rubio has the EQUITY STRATEGIST potential to cause significant change in the listing domains of [email protected] +852 2848-7135 Chinese firms. After the market close in the US yesterday 4th June the Wall Street Journal published an Op-Ed by US Senator Marco Rubio in which he announced that he intends to sponsor the “Equitable Act” – an acronym for Ensuring Quality Information and Transparency for Abroad-Based Listings on our Exchanges. At this time the text of the bill has not been published and we are seeking additional information about its contents and likelihood of passing. However, our early reaction is that this has the potential to cause significant changes in the domain for listings of Chinese firms going forward with the potential for de- listing of Chinese firms on US exchanges and re-listing elsewhere (most likely Hong Kong). More generally we see this development as part of an increased escalation of tensions between China and the US on multiple fronts which should cap the valuation multiple for China equities, in particular in the offshore index constituents and US-listed parts of the universe. We provide a list of the potentially impacted China / HK names with either primary or secondary listings on Amex, NYSE or Nasdaq. -

Haier Electronics

The role of the Belt and Road Initiative on Chinese multinational enterprise strategy: a multiple case study A Master Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Economics and Business by Justin Brandsma S2734818 Supervisor: H.U. Haq Co-assessor: J.R. de Wit WC: 16484 June 2020 Groningen, The Netherlands The role of the BRI on Chinese MNE strategy 2 The role of the BRI on Chinese MNE strategy Foreword In front of you lies my master thesis on: “the Role of the Belt and Road Initiative on Chinese multinational strategy: a multiple case study“, written as part of the master’s degree in International Business and Management at the University of Groningen. I consider this thesis to be the culmination of 6 beautiful student years in the even more beautiful city of Groningen, a wonderful period of my life! My choice for this thesis topic dates back to my late middle-school and early high-school years where I developed a big interest in the ancient Greek history and mythology. Especially the tales of Alexander the Great who managed to expand the Macedonian empire all the way to northeast India were intriguing to me. This Greek venture East in 334BC led to the establishment of the earliest version of a trade route between Constantinople (Turkey) and Xi’an (China), known as the Silkroad. 1600 years later Marco Polo would travel this route from Venice to China and work as the personal advisor of the Mongolian ruler: Kublai Khan. The accumulation of his experiences and adventures in the East came together in the brilliant travel memoire written by Rusticello da Pisa named ‘il Milione’ or commonly known as the ‘the travels of Marco Polo’. -

TCL MULTIMEDIA TECHNOLOGY HOLDINGS LIMITED TCL 多媒體科技控股有限公司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 01070)

THIS DOCUMENT AND THE ACCOMPANYING DOCUMENTS (IF ANY) ARE IMPORTANT AND REQUIRE YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt as to any aspect of this Prospectus or as to the action to be taken, you should consult your stockbroker or other licensed securities dealer, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional adviser. If you have sold or transferred all your Shares, you should at once hand the Prospectus Documents to the purchaser(s) or the transferee(s) or to the bank, the licensed securities dealer or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser(s) or transferee(s). A copy of each of the Prospectus Documents, together with a copy of the documents specified in the section headed “Documents delivered to the Registrar of Companies” in Appendix III to this Prospectus, has been registered with the Registrar of Companies in Hong Kong as required by Section 342C of the Companies (Winding Up and Miscellaneous Provisions) Ordinance. The Registrar of Companies in Hong Kong, the Stock Exchange and the SFC take no responsibility as to the contents of any of these documents. You should read the whole of this Prospectus including the discussions of certain risks and other factors as set out in the section headed “WARNING OF THE RISKS OF DEALING IN SHARES AND NIL PAID RIGHTS” of this Prospectus. Subject to the granting of approval for the listing of, and permission to deal in, the Rights Shares in both nil-paid and fully-paid forms on the Stock Exchange as well as compliance with the stock admission requirements of HKSCC, the Rights Shares in both nil-paid and fully-paid forms will be accepted as eligible securities by HKSCC for deposit, clearance and settlement in CCASS with effect from the respective commencement dates of dealings in the Rights Shares in their nil-paid and fully-paid forms on the Stock Exchange. -

Phase Exhibitior Section Stand Number 1 SASSIN INTERNATIONAL ELECTRIC SHANGHAI CO.,LTD

VIP Exhibitors of the 114th Session of Canton Fair Phase Exhibitior Section Stand Number 1 SASSIN INTERNATIONAL ELECTRIC SHANGHAI CO.,LTD. Electronic and Electrical Products 5.1A09-22 1 SICHUAN JIUZHOU ELECTRIC GROUP CO., LTD. Consumer Electronics 11.3C35-46 1 Guangzhou Midea Hualing Refrigerator Co., Ltd. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2A77-92 1 GREE ELECTRIC APPLIANCES,INC.OF ZHUHAI Household Electrical Appliances 4.2A51-78 1 MIDEA GROUP CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2A09-60 1 HAIER GROUP Household Electrical Appliances 3.2B01-54 1 GUANGDONG XINBAO APPLIANCES HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 4.2F31-47 1 NO.168 HUANCHENG EAST RD.ZHOUXIANG CIXI,NINGBO P.R.C. Household Electrical Appliances 4.2F19-30 1 NINGBO AUX IMP.& EXP CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 4.2D13-46 1 XINGXING GROUP CO.,LTD Household Electrical Appliances 4.2I07-21 1 TCL CORPORATION Household Electrical Appliances 3.2G41-60 1 GUANGDONG GALANZ ENTERPRISE CO., LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 4.2A06-45 1 Guangzhou Wanbao Group Co.,Ltd. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2E50-67 1 GUANGDONG CHIGO AIR CONDITIONING CO.LTD Household Electrical Appliances 4.2D51-71 1 Homa Appliances Co., Ltd Household Electrical Appliances 3.2C01-12 1 NINGBO KAIBO GROUP CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 2.2D37-42,2.2E07-12 1 NINGBO XINLE HOUSEHOLD APPLIANCES CO., LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2C85-96 1 SICHUAN CHANGHONG ELECTRIC CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2E20-35 1 NINGBO LAMO ELECTRIC APPLIANCE CO.,LTD. Household Electrical Appliances 3.2G29-40 1 HEFEI MEILING COMPANY LIMITED Household Electrical Appliances 3.2E36-49 1 CUORI ELECTRICAL APPLICANAES GROUP CO.,LTD. -

Hisense Kelon Electrical Holdings Company Limited 海信科龍電器股份有限公司

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. HISENSE KELON ELECTRICAL HOLDINGS COMPANY LIMITED 海信科龍電器股份有限公司 (A joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 00921) DISCLOSEABLE TRANSACTIONS SUBSCRIPTION OF WEALTH MANAGEMENT PRODUCTS Reference is made to the announcements of the Company dated 1 September 2016 and 7 September 2016 in respect of the August Wealth Management Agreement, the First September Wealth Management Agreement and the Second September Wealth Management Agreement, pursuant to which Hisense Refrigerator (as subscriber) subscribed for the wealth management products in the aggregate subscription amount of RMB900,000,000 (equivalent to approximately HK$1,045,504,145Note 1) from the Agricultural Bank of China (as issuer). The Board is pleased to announce that apart from the August Wealth Management Agreement, the First September Wealth Management Agreement and the Second September Wealth Management Agreement, on 26 September 2016, Hisense Refrigerator entered into the Third September Wealth Management Agreement with the Agricultural Bank of China to subscribe for the 75-day Wealth Management Product in the subscription amount of RMB200,000,000 (equivalent to approximately HK$232,660,943Note 2). The Third September Wealth Management Agreement by itself does not constitute discloseable transaction of the Company under Rule 14.06 of the Listing Rules. -

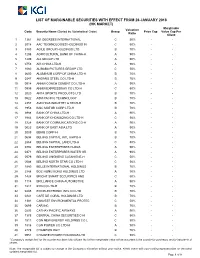

HK Marginable List

LIST OF MARGINABLE SECURITIES WITH EFFECT FROM 26 JANUARY 2018 (HK MARKET) Marginable Valuation Code Security Name (Sorted by Alphabetical Order) Group Price Cap Value Cap Per Ratio Client 1 1361 361 DEGREES INTERNATIONAL C 50% - - 2 2018 AAC TECHNOLOGIES HOLDINGS IN C 50% - - 3 3383 AGILE GROUP HOLDINGS LTD B 70% - - 4 1288 AGRICULTURAL BANK OF CHINA-H A 90% - - 5 1299 AIA GROUP LTD A 90% - - 6 0753 AIR CHINA LTD-H A 90% - - 7 1060 ALIBABA PICTURES GROUP LTD C 50% - - 8 2600 ALUMINUM CORP OF CHINA LTD-H B 70% - - 9 0347 ANGANG STEEL CO LTD-H B 70% - - 10 0914 ANHUI CONCH CEMENT CO LTD-H A 90% - - 11 0995 ANHUI EXPRESSWAY CO LTD-H C 50% - - 12 2020 ANTA SPORTS PRODUCTS LTD B 70% - - 13 0522 ASM PACIFIC TECHNOLOGY B 70% - - 14 2357 AVICHINA INDUSTRY & TECH-H B 70% - - 15 1958 BAIC MOTOR CORP LTD-H B 70% - - 16 3988 BANK OF CHINA LTD-H A 90% - - 17 1963 BANK OF CHONGQING CO LTD-H C 50% - - 18 3328 BANK OF COMMUNICATIONS CO-H A 90% - - 19 0023 BANK OF EAST ASIA LTD A 90% - - 20 2009 BBMG CORP-H B 70% - - 21 0694 BEIJING CAPITAL INTL AIRPO-H B 70% - - 22 2868 BEIJING CAPITAL LAND LTD-H C 50% - - 23 0392 BEIJING ENTERPRISES HLDGS A 90% - - 24 0371 BEIJING ENTERPRISES WATER GR A 90% - - 25 0579 BEIJING JINGNENG CLEAN ENE-H C 50% - - 26 0588 BEIJING NORTH STAR CO LTD-H C 50% - - 27 1880 BELLE INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS B 70% - - 28 2388 BOC HONG KONG HOLDINGS LTD A 90% - - 29 1428 BRIGHT SMART SECURITIES AND C 50% - - 30 1114 BRILLIANCE CHINA AUTOMOTIVE A 90% - - 31 1211 BYD CO LTD-H B 70% - - 32 0285 BYD ELECTRONIC INTL CO LTD B 70% - - 33 0341 CAFE DE CORAL HOLDINGS LTD B 70% - - 34 1381 CANVEST ENVIRONMENTAL PROTEC C 50% - - 35 0699 CAR INC B 70% - - 36 0293 CATHAY PACIFIC AIRWAYS A 90% - - 37 1375 CENTRAL CHINA SECURITIES C-H C 50% - - 38 1811 CGN NEW ENERGY HOLDINGS CO L C 50% - - 39 1816 CGN POWER CO LTD-H A 90% - - 40 2778 CHAMPION REIT B 70% - - 41 0951 CHAOWEI POWER HOLDINGS LTD C 50% - - * Company's margin limit for the counter has been fully utilized. -

Annual Report 2018

2018 Annu Al RepoRt (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) Stock Code: 772 CONTENTS 2 Corporate Information 4 Financial Summary and Operational Highlights 6 Chairman’s Statement 9 Management Discussion and Analysis 22 Directors and Senior Management 27 Report of Directors 61 Corporate Governance Report 78 Environmental, Social and Governance Report 90 Independent Auditor’s Report 100 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 101 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 103 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 105 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 107 Notes to Financial Statements 228 Definitions CHINA LITERATURE LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CORPORATE INFORMATION Board of Directors Joint Company Secretaries Mr. Zhao Jincheng Executive Directors Ms. Lai Siu Kuen Mr. Wu Wenhui (Co-Chief Executive Officer) Mr. Liang Xiaodong (Co-Chief Executive Officer) Legal Advisors As to Hong Kong laws: Non-executive Directors Clifford Chance Mr. James Gordon Mitchell (Chairman) 27/F, Jardine House Mr. Lin Haifeng One Connaught Place Ms. Li Ming Hong Kong Mr. Yang Xiang Dong As to Cayman Islands laws: Independent Non-executive Directors Maples and Calder (Hong Kong) LLP Ms. Yu Chor Woon Carol 53rd Floor, The Center Ms. Leung Sau Ting Miranda 99 Queen’s Road Central Mr. Liu Junmin Hong Kong Audit Committee Auditor Ms. Yu Chor Woon Carol (Chairman) PricewaterhouseCoopers Mr. Yang Xiang Dong Certified Public Accountants Ms. Leung Sau Ting Miranda 22/F, Prince’s Building Central Remuneration Committee Hong Kong Ms. Leung Sau Ting Miranda (Chairman) Mr. Wu Wenhui Compliance Advisor Ms. Yu Chor Woon Carol Guotai Junan Capital Limited 27/F, Low Block Grand Millennium Plaza Nomination Committee 181 Queen’s Road Central Mr. -

Retirement Funds June 30, 2017 Description % Invested UAE

Retirement Funds June 30, 2017 Note: Some percentages in the retirement funds vary due to lagged valuations that are used to produce the annual audited financials. Description % Invested UAE DIRHAM 0.000000% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.000692% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.000000% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.008138% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.000033% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.000012% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.000898% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.001207% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.000000% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.000082% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.000184% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.000072% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.000653% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.000064% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.015170% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.000038% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.001767% SWISS FRANC 0.000009% SWISS FRANC 0.000020% SWISS FRANC 0.000033% SWISS FRANC 0.000005% CHILEAN PESO 0.000204% YUAN RENMINBI 0.000278% COLOMBIAN PESO 0.000004% DANISH KRONE 0.000000% DANISH KRONE 0.000005% DANISH KRONE 0.000033% EURO CURRENCY 0.000000% EURO CURRENCY 0.000514% EURO CURRENCY 0.002592% EURO CURRENCY 0.000039% EURO CURRENCY 0.000000% EURO CURRENCY 0.000006% EURO CURRENCY 0.009224% POUND STERLING 0.000183% POUND STERLING 0.000508% POUND STERLING 0.010828% POUND STERLING 0.000000% POUND STERLING 0.000037% POUND STERLING 0.001188% POUND STERLING 0.000007% POUND STERLING 0.000000% POUND STERLING 0.003296% HONG KONG DOLLAR 0.000381% HONG KONG DOLLAR 0.000291% HONG KONG DOLLAR 0.000909% HONG KONG DOLLAR 0.000971% HONG KONG DOLLAR 0.000302% HONG KONG DOLLAR 0.000032% HONG KONG DOLLAR 0.001472% HONG KONG DOLLAR 0.000131% HONG KONG DOLLAR 0.003240% HUNGARIAN FORINT 0.000154% HUNGARIAN FORINT 0.000063% INDONESIAN -

Initiation INDUSTRY N M INDU STRY ME E

Initiation Company Report Consumer E INDUSTRY NM INDUSTRYME NM INDUSTRY How to make the impossible mission possible? February 26, 2019 Two roads diverge in the triathlon track Research Team Tianli Wen ● Xiaomi today as a regional and marketing innovator faces an uphill battle against Head of Research Huawei, a global and technology innovator. Yet Xiaomi’s user base, Internet root and brand loyalty are its key strength. As Internet-Of-Things (IOT) taking root, the Tris X. Gong battle ground will shift to Xiaomi’s favour; ● We suggest Xiaomi to focus on two areas to enhance its valuation: (1) developing +852 21856112 Internet content, (2) spending on R&D. Both require a healthy cash flow, which [email protected] makes margin and profitability improvement imperative; ● Given Xiaomi’s near-term challenges as a global company, we rate the stock a HOLD with a TP of HK$14.55. Xiaomi’s brand, Mi, stands for Mission Impossible. See the last page of the report for important disclosures Blue Lotus Capital Advisors Limited 1 China|Asia ●Initiation Consumer ● Electronics Xiaomi Inc. (HK: 1810) Making the impossible mission possible BUY HOLD SELL ● We initiate Xiaomi with a HOLD rating and TP of HK$14.55 because we Target Price: HK$ 14.55 Current Price: HK$ 12.20 Initiation believe Xiaomi still need to hone its skills as either a technology champion RIC: (HK:1810) BBG: 1810 HK Market cap (HK$ mn) 291,500 like Huawei, or a platform+content powerhouse like Tencent, or both; Average daily volume (HK$ mn) 678 ● Xiaomi’s near-term challenge is to achieve greater profitability so that it can Shares out/float (mn) 17,204/4,360 Source: Bloomberg, Blue Lotus (as of Feb 26, 2019) further build up Internet services and play in the technology top league; ● Global expansion and content are opportunities. -

Hisense Kelon Electrical Holdings Small Blue Chip on Rise, Valuation Continues to Improve

Equity Research March 15, 2017 Hisense Kelon Electrical Holdings Small blue chip on rise, valuation continues to improve Company Update Maintain BUY What's new Ticker 000921.SZ 00921.HK The company's share price exceeded our target price. CICC investment rating HOLD BUY Last close Rmb14.67 HK$10.60 CICC target Rmb13.50 HK$13.70 Comments Valuation continues to improve: 1) Hisense Kelon was 52wk price range Rmb14.44~6.68 HK$10.14~2.69 treated as a small-cap stock in the past and its valuation has Market cap (bn) Rmb18 HK$20 been underestimated; and, 2) profit distributed by subsidiary Daily value (mn) Rmb181.10 HK$36.72 Hisense Hitachi accounted for >50% of the company’s operating Shares outstanding (mn) 1,363 1,363 Free float (%) 66 34 profits in 2016 and will keep growing rapidly. The company’s Daily volume (mn sh) 14.26 3.98 valuation is expected to improve and it will gradually be identified Business sector Home Appliances & Electronics as a small to medium-sized blue chip. 00921.HK HSCEI Hisense Hitachi is very competitive and will benefit 368 from: 1) explosive growth in household VRF market brought by 301 consumption upgrades in tier-1/-2 cities. Hisense Hitachi utilized 234 the Hitachi brand, low base, and Hisense’s local channel advantages to achieve rapid growth in market share. China’s 167 current household VRF penetration rate is <5%; it is expected to (%) Value Relative 100 grow >20% in the future. And, 2) Hisense Kelon only holds a 33 49% stake in Hisense Hitachi, the main driver of Hisense Kelon’s Mar-2016 Jun-2016 Sep-2016 Dec-2016 Mar-2017 future profit growth. -

Haier Electronics Product Competitiveness Brought Business Improvement

Equity Research December 15, 2016 Haier Electronics Product competitiveness brought business improvement Investment Focus Maintain BUY Action Ticker 01169.HK Haier Electronics is a global bellwether in home appliances and CICC investment rating BUY Last close HK$12.40 stands to benefit from product competitive improvement in 2017. Set TP at Rmb16.2 (13x 2017e P/E) and maintain BUY. CICC target HK$16.20 52wk price range HK$15.63~10.73 Market cap (bn) HK$35 Reasoning Daily value (mn) HK$34.99 Haier Electronics’ home appliance business is improving. Shares outstanding (mn) 2,792 1) Product competitiveness enhanced. 2) The original sales Free float (%) 100 system managed by both Qingdao Haier and Haier Electronics is Daily volume (mn sh) 2.72 Business sector Home Appliances & Electronics integrated in 2016. Channel efficiency improved. 3) Air conditioner turnaround boosts RRS channel business. 01169.HK HSCEI 118 Washing machine business turning around in 4Q16. 1) 109 The company has been promoting laser welding cylinder, FPA variable frequency motors. Product competitiveness improved 100 significantly. 2) Washing machines and refrigerators are 91 gradually targeting the high-end and customization market. (%) Value Relative 82 Casarte has become the leading brand among Rmb10k products. 73 In 2H16, ASP gradually moves down to match that of Siemen‟s; Dec-2015 Mar-2016 Jun-2016 Sep-2016 Dec-2016 trying to take market share from foreign brands. High-margin Casarte and customized products contribute 10% of total (Rmb mn) 2014A 2015A 2016E 2017E washing machine sales. 3) In 4Q16, we observed that Haier‟s Revenue 67,134 62,826 62,131 66,298 share in the washing machine market began to increase.