Teaching 20Th-Century European History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

Legal Studies Research Paper Series

Unlimited War and Social Change: Unpacking the Cold War’s Impact Mary L. Dudziak USC Legal Studies Research Paper No. 10-15 LEGAL STUDIES RESEARCH PAPER SERIES University of Southern California Law School Los Angeles, CA 90089-0071 Unlimited War and Social Change: Unpacking the Cold War’s Impact Mary L. Dudziak Judge Edward J. and Ruey L. Guirado Professor of Law, History and Political Science USC Gould Law School September 2010 This paper is a draft chapter of WAR · TIME: A CRITICAL HISTORY (under contract with Oxford University Press). For more on this project, see Law, War, and the History of Time (forthcoming California Law Review): http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1374454. NOTE: This is very much a working draft, not a finished piece of work. I would be grateful for any comments and criticism. I can be reached at: [email protected]. copyright Mary L. Dudziak © 2010 Unlimited War and Social Change: Unpacking the Cold War’s Impact Abstract This paper is a draft chapter of a short book critically examining the way assumptions about the temporality of war inform American legal and political thought. In earlier work, I show that a set of ideas about time are a feature of the way we think about war. Historical progression is thought to consist in movement from one kind of time to another (from wartime to peacetime, to wartime, etc.). Wartime is thought of as an exception to normal life, inevitably followed by peacetime. Scholars who study the impact of war on American law and politics tend to work within this framework, viewing war as exceptional. -

Alternative 2020

Mediabase Charts Alternative 2020 Published (U.S.) -- Currents & Recurrents January 2020 through December, 2020 Rank Artist Title 1 TWENTY ONE PILOTS Level Of Concern 2 BILLIE EILISH everything i wanted 3 AJR Bang! 4 TAME IMPALA Lost In Yesterday 5 MATT MAESON Hallucinogenics 6 ALL TIME LOW Monsters f/blackbear 7 ABSOFACTO Dissolve 8 POWFU Coffee For Your Head 9 SHAED Trampoline 10 UNLIKELY CANDIDATES Novocaine 11 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Black Madonna 12 MACHINE GUN KELLY Bloody Valentine 13 STROKES Bad Decisions 14 MEG MYERS Running Up That Hill 15 HEAD AND THE HEART Honeybee 16 PANIC! AT THE DISCO High Hopes 17 KILLERS Caution 18 WEEZER Hero 19 TWENTY ONE PILOTS The Hype 20 WALLOWS Are You Bored Yet? 21 LOVELYTHEBAND Broken 22 DAYGLOW Can I Call You Tonight? 23 GROUPLOVE Deleter 24 SUB URBAN Cradles 25 NEON TREES Used To Like 26 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Social Cues 27 WHITE REAPER Might Be Right 28 BLACK KEYS Shine A Little Light 29 LUMINEERS Life In The City 30 LANA DEL REY Doin' Time 31 GREEN DAY Oh Yeah! 32 MARSHMELLO Happier f/Bastille 33 AWOLNATION The Best 34 LOVELYTHEBAND Loneliness For Love 35 KENNYHOOPLA How Will I Rest In Peace If... 36 BAKAR Hell N Back 37 BLUE OCTOBER Oh My My 38 KILLERS My Own Soul's Warning 39 GLASS ANIMALS Your Love (Deja Vu) 40 BILLIE EILISH bad guy 41 MATT MAESON Cringe 42 MAJOR LAZER F/MARCUS Lay Your Head On Me 43 PEACH TREE RASCALS Mariposa 44 IMAGINE DRAGONS Natural 45 ASHE Moral Of The Story f/Niall 46 DOMINIC FIKE 3 Nights 47 I DONT KNOW HOW BUT THEY.. -

Paper 18 European History Since 1890

University of Cambridge, Historical Tripos, Part I Paper 18 European History since 1890 Convenor: Dr Celia Donert (chd31) “Apartment” in Berlin, 1947 Reading List* 2020-21 *Please see the Paper 18 Moodle page for reading lists containing online- only resources. 1 Course Description _______________________________________________________________ 3 Films ___________________________________________________________________________ 4 Online resources _________________________________________________________________ 4 An Introduction to 20th Century Europe ______________________________________________ 5 Mass Politics and the European State ________________________________________________ 6 Mass Culture ____________________________________________________________________ 7 The political economy of 20th century Europe ________________________________________ 10 War and Violence _________________________________________________________________ 9 Gender, sexuality and society ______________________________________________________ 11 France and Germany Before 1914 ___________________________________________________ 12 The Russian and Habsburg Empires before 1914 ______________________________________ 16 The Origins of the First World War _________________________________________________ 14 The First World War _____________________________________________________________ 19 Revolutionary Europe, 1917-21 _____________________________________________________ 21 Modernist culture _______________________________________________________________ 23 The -

1 Sabancı University HIST 205: History of the Twentieth

HIST 205 syllabus Fall 2018 SU 1 Sabancı University HIST 205: History of the Twentieth Century Instructor: Ayşe Ozil Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Fall 2018 Mondays 12:40-15.30, FASS G049 Course content: This course offers an introduction to twentieth century history. The focus is on Europe from the beginning of the First World War to the end of the Cold War (1914- 1991). Particularly, the course deals with the two world wars, the inter-war period, and the Golden Age, and ends with references to the Cold War. Students are expected to learn the main events and major developments of the period and have a grasp of the characteristics and workings of politics and society, particularly around the epochal changes of the first half of the last century. Assessment and evaluation: % 40 mid-term examination % 60 final examination Both examinations are composed of 5 short and 2 longer essay questions. The final exam covers the entire course work. Attendance: Students are expected to attend every class. Attendance will be taken. Students who make absences will have points subtracted from their final grade. Students are expected to check sucourse on a regular basis for weekly pacing and announcements. Course outline: Week 1, Sep 24 Introduction and background Periodization and basic factography of the twentieth century; an overview of politics, ideology, technology, society, and culture in the nineteenth century Week 2, Oct 1 The run-up to World War I Europe at the threshold of the 20th century; politics of the Great Powers of Britain, France, -

Edgar Rice Burroughs

Innon syksy 2012 Into Kustannus Hämeentie 48, 00500 Helsinki TIEDUSTELUT: Jaana Airaksinen 045 633 4495, Timo K. Forss 040 533 2961 [email protected], [email protected] www.intokustannus.fi Innon syksy 2012 SISäLLySLUETTELo 2 Saara Henriksson LInnUnpAIno 3 Jaakko Laitinen KUoLEmA ULAn BatorISSA 4 Suvi Hurmelinna & Stan Ström KIpUKynnyS 5 Andrea Levy pITKä LAULU 6 Adam Mansbach & Richardo Cortés mEnE v***U nUKKUmAAn 7 Mr. Fish pILAKUvIA pErSEESTä 1 8 Phil Andros KUIn KrEIKKALAISET 8 Phil Andros poLIISISArJA 9 Edgar Rice Burroughs JoHn CArTEr 3 – mArSIn SoTAvALTIAS 10 Li Andersson, Mikael Brunila & Dan Koivulaakso äärIoIKEISTo SUomESSA 11 Esko Seppänen EmUmUnAUS 12 Heikki Hiilamo KIrJEITä TyTTärELLEnI 13 Pirjo Kainulainen AmmattinA poTILAS 14 Jussi Förbom väKI, valta JA vIrASTo 15 Emma Kari & Kukka Ranta ryöSTETTy mErI 16 Anna Kontula mISTä EI voI pUHUA 17 Olli Tammilehto KyLmä SUIHKU 18 Kimmo Kiljunen mAAILmAn maat 19 Anne Hämäläinen, Sanni Seppo & Pirjo Aaltonen AnnA AHmatovA FontanKAn taloSSA 20 Ulla Pyyvaara & Arto Timonen katu 21 Kati Pietarinen (toim.) poISSA SIJoiltaan 22 Jari Tamminen HäIrIKöT 23 Paul Verhoeven JEESUS nASArETILAInEn 24 Luke Harding mAFIAvaltio 25 Oksana Tšelyševa HE SEUrASIvat mInUA KADULLA 26 Ha-Joon Chang 23 ToSIASIAA KApitalismista 27 Ignacio Ramonet TIEDonväLITyKSEn räJäHDyS 28 Gérard Prunier AFrIKAn mAAILmAnSota 29 Paul Stenning rAgE AgAInST THE mACHInE 30 Maarit Korhonen KoULUn vIKA? 31 Saila Kivelä & Karry Hedberg SIKALASSA 32 Juha Honkonen & Jussi Lankinen HUonoJA UUTISIA 33 Sirpa Puhakka pErIn SUomALAInEn JyTKy 34 Catharine Grant ELäInTEn oIKEUDET 35 Pekka Borg SUmUmETSISTä pAAHDErInTEILLE Into Kustannus Hämeentie 48, 00500 Helsinki TIEDUSTELUT: Jaana Airaksinen 045 633 4495, Timo K. Forss 040 533 2961 [email protected], [email protected] www.intokustannus.fi Innon syksy 2012 kauno KUn EmmE muuta oSAnnEET SAnoA ITSELLEmmE tai ToISILLEmmE, jatkoImmE tanSSImista. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Aft;? Enpl (Saeptte Aitft Qlnlmtiat 'Lathj INCORPORATING Fhe ROYAL GAZETTE -Established 1828) and the BERMUDA COLONIST (Established 1866)

_3^ TODAY'S LIGHTING-UP TIME Sunrise: 7,07 a.m.—Sunset: 6.00 p.m. Lighting-up time: 6.30 p.m. Rule of Road: KEEP LEFT-^PASS ON THE RIGHT aft;? Enpl (SaEPtte aitft Qlnlmtiat 'lathj INCORPORATING fHE ROYAL GAZETTE -Established 1828) and THE BERMUDA COLONIST (Established 1866) VOL. 19—NO. 37 HAMILTON, BERMUDA, MONDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 1934 3D PER COPY—40/- PER ANNUM s& NAVAL AUTHOR CRITICIZES BRITAIN'S SHIPS MAGISTRATE STATES CASE GOVERNMENT HOUSE i YACHTING PARIS STILL IN TURMOIL : THEYJAY m NOVEL *HARGE The following were entertained by His Excellency the Governor and Eldon Trimingham Sails Princess That the news of the Hodsdon's U. Sa ARMY TAXES OVER AIR MAIL Owner Not Responsible for Lady Cubitt at Dinner at Govern to Victory in One Designs shelter was warmly appreciated. ment House on Saturday, Febru • * * Keeping Dog off Street ary 10th. Wednesday afternoon saw the That but for pressure of work at second race of the Winter Cham the P.W.D. it might have been Hurting Chaplain Made Dean of Bristol—Storm- Acting Magistrate Donald C. Mr. and Mrs. J. D. B. Talbot. Smith yesterday gave a stated case pionship for the Bermuda One built some time ago. Lt. Col. and Mrs. J. Baxendale. * * i Wrecked Ship's Crew Rescued—Nine Mur in the Hamilton Police Court on a Designs. Six starters came to case of some interest because of Captain and Mrs. F. 0. Misick. the line with Eldon Trimingham That the progress on the St. David's derers Die for Crimes—Canada Test Ship the somewhat unusual nature of Major and Mrs. -

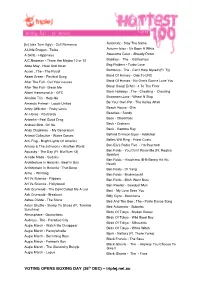

(26Th DEC) – Triplej.Net.Au

1 of 12 [Is] (aka Tom Ugly) - Cult Romance Autokratz - Stay The Same A Little Dragon - Twice Autumn Isles - It's Been A While A Skillz - Happiness Awesome Color - Already Down A.C.Newman - There Are Maybe 10 or 12 Baddies - The - Battleships Abbe May - Howl And Moan Bag Raiders - Turbo Love Acorn , The - The Flood Bamboos , The - Can't Help Myself (Ft. Ty) Adam Green - Festival Song Band Of Horses - Ode To LRC After The Fall - Cut Your Losses Band Of Horses - No One's Gonna Love You After The Fall - Break Me Bang! Bang! Eche! - 4 To The Floor Albert Hammond Jr - GFC Bank Holidays , The - Cheating - Cheating Alkaline Trio - Help Me Basement Jaxx - Wheel N Stop Amanda Palmer - Leeds United Be Your Own Pet - The Kelley Affair Amity Affliction - Fruity Lexia Beach House - Gila An Horse - Postcards Beaches - Sandy Anberlin - Feel Good Drag Beck - Chemtrails Andrew Bird - Oh No Beck - Orphans Andy Clockwise - My Generation Beck - Gamma Ray Animal Collective - Water Curses Behind Crimson Eyes - Addicted Anti-Flag - Bright Lights Of America Belles Will Ring - Priest Coats Antony & The Johnsons - Another World Ben Ely's Radio Five - I'm Psyched Aquasky - The Day (Ft. Blu Rum 13) Ben Folds - You Don't Know Me (Ft. Regina Spektor) Arcade Made - Sudoku Ben Folds - Hiroshima (B-B-Benny Hit His Architecture In Helsinki - Beef In Box Head) Architecture In Helsinki - That Beep Ben Folds - Dr Yang Arms - Whirring Ben Folds - Brainwascht Art Vs Science - Flippers Ben Folds - Bitch Went Nuts Art Vs Science - Hollywood Ben Kweller - Sawdust Man Ash Grunwald - The Devil Called Me A Liar Beni - My Love Sees You Ash Grunwald - Breakout Biffy Clyro - Mountains Ashes Divide - The Stone Bird And The Bee , The - Polite Dance Song Aston Shuffle - Stomp Yo Shoes (Ft. -

The Russian Revolution After One Hundred Years

Copyright @ 2017 Australia and New Zealand Journal of European Studies https://cesaa.org.au/anzjes/ Vol9 (3) ISSN 1837-2147 (Print) ISSN 1836-1803 (On-line) Graeme Gill The University of Sydney [email protected] The Russian Revolution After One Hundred Years Abstract The Russian revolution was the defining episode of the twentieth century. It led to the transformation of Russia into one of the superpowers on the globe, but one that exhibited a development model that was both different from and a challenge to the predominant model in the West. The Soviet experiment offered a different model for organising society. This was at the basis of the way in which international politics in the whole post-second world war period was structured by the outcome of the Russian revolution. But in addition, that revolution helped to shape domestic politics in the West in very significant ways. All told, the revolution was of world historical and world shaping importance. Key words: cold war; communism; development models; left-wing politics; Russian revolution; socialism After one hundred years, the Russian revolution remains a matter of vigorous scholarly contention. Although in the eyes of many the evaluative question has been settled—the system of communism created by the revolution has failed—the question of how the revolution is to be understood remains a hot topic, as many of the publications that have come out around the centenary show. Is the revolution best seen as part of the general imperial collapse resulting from the First World War?1 Should it be seen as part of a European (Germany, Hungary) or a Eurasian (China, Iran, Turkey) wave of revolution?2 Some writers focus on the February revolution and its antecedents,3 some on the year 1917.4 Other authors frame the revolution as lasting up to 1921 and the New Economic Policy (NEP)5 or to the late 1920s when Stalin launched his “revolution from above”. -

PRESS RELEASE What: the Sound Strike Press Conference

PRESS RELEASE What: The Sound Strike Press Conference When: Wednesday July 21st 11am Where: Hollywood Palladium 6215 W. Sunset Blvd. Hollywood, CA 90028 Who: • Zack de la Rocha, Vocalist Rage Against the Machine • Tom Morello, Guitarist Rage Against the Machine • Conor Oberst, Vocalist Mystic Valley Band • Dolores Huerta, Co-Founder United Farm Workers (UFW) Contact: Javier Gonzalez, [email protected]. Phone: (213) 598-8907 SOUNDSTRIKE ARTISTS RAGE AGAINST THE MACHINE, CONOR OBERST AND THE MYSTIC VALLEY BAND HOLD PRESS CONFERENCE REGARDING BENEFIT CONCERT TO SUPPORT ORGANIZATIONS FIGHTING ARIZONA ANTI-IMMIGRANT LAW SB 1070. LOS ANGELES, CA July 21: Rage Against the Machine will play their first concert in Los Angeles in 10 years at the Hollywood Palladium Friday with all proceeds going to benefit Arizona organizations fighting SB 1070. Oberst and The Mystic Valley Band will also perform. Benefit concert performers will be joined by long time civil and immigrant rights activists Tom Seanz, President of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF), Dolores Huerta, Co- Founder of the United Farm Workers (UFW), Arizona grass roots leader Sal Reza of Puente, and other community leaders. This will be the Soundstrike’s first official press conference. The SoundStrike artist boycott of Arizona has gained international attention and support. Hundreds of artists have committed to exercise their conscious and their collective power to both reverse the punitive, discriminatory and misguided Arizona law as well as to help lead a more productive national debate on diversity and unity. Soundstrike participant and Rage vocalist Zack de la Rocha said, “SB 1070 if enacted would legalize racial profiling in Arizona. -

For a Whole Lifetime a Students Delight in Something Which Ought to Be His/Her Birthright

1 www.onlineeducation.bharatsevaksamaj.net www.bssskillmission.in “Music Appreciation”. In Section 1 of this course you will cover these topics: From The Creator To The Listener What To Listen For In Music Becoming A Musically Aware Concertgoer How The Basic Musical Elements Interact Performing Media: Instruments, Voices, And Ensembles An Introduction To Musical Styles Topic : From The Creator To The Listener Topic Objective: At the end of this topic student would be able to: Learn the Music and Speech Develop good Listening skills Get familiar and use the Gregorian Chant Develop a clear understanding of the Anatomy of Music: A Learning Tool for Listening Definition/Overview: Unfortunately, not every student loves music. Distorted on monotonous perception of musical sound may spoilWWW.BSSVE.IN for a whole lifetime a students delight in something which ought to be his/her birthright. But some students troubles do not stop there. They are often afflicted by underachievement in other areas of listening. They are poor, one could almost say disabled, listeners. But listening can be improved and the love for music can be regained. And in what it seems to be a paradox, music can play a key role in the restitution of listening. Key Points: 1. Music and Listening Music is made up of two elements: rhythm and melody. The inner ear, being the sensory part of the ear, seems to be perfectly conceived for the integration of music. The inner ear is actually made up of two parts: the vestibular system and cochlear system. The vestibular www.bsscommunitycollege.in www.bssnewgeneration.in www.bsslifeskillscollege.in 2 www.onlineeducation.bharatsevaksamaj.net www.bssskillmission.in system controls balance and body movements.