Cross-Linguistic Patterns of Vowel Intrusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manner of Articulation

An Animated and Narrated Glossary of Terms used in Linguistics presents Manner of Articulation Articulators Slide 2 Page 1 Manner of Articulation • The manner of articulation refers to the way airflow is controlled in the production of a phone (i.e. a linguistic sound). Slide 3 Manner of Articulation on the IPA Chart Plosive Nasal Trill Tap or Flap Fricative Lateral fricative Approximant Lateral approximant Manner of articulation Slide 4 Page 2 Plosive p Plosives require total obstruction of airflow. Slide 5 Nasal n Nasals require air to flow out of the nose. Slide 6 Page 3 Trill r Trills are made by rapid succession of contact between articulators that obstruct airflow. Slide 7 Tap or Flap A tap or flap is like trill, except that there is only one rapid contact between the articulators. There is some difference between tap and flap, but we shall not pursue that here. Slide 8 Page 4 Fricative f A fricative is formed when the stricture is very narrow (but without total closure) so that when air flows out, a hissing noise is made. Slide 9 Approximant An approximant is a phone made when the obstruction of airflow does not produce any audible friction. Slide 10 Page 5 Lateral l A lateral is made when air flows out of the sides of the mouth. Slide 11 Note • In this presentation, we have concentrated on the pulmonic consonants, but manners of articulation may be used to describe vowels and other linguistic sounds as well. Slide 12 Page 6 The End Wee, Lian-Hee and Winnie H.Y. -

On the Phonetic Nature of the Latin R

Eruditio Antiqua 5 (2013) : 21-29 ON THE PHONETIC NATURE OF THE LATIN R LUCIE PULTROVÁ CHARLES UNIVERSITY PRAGUE Abstract The article aims to answer the question of what evidence we have for the assertion repeated in modern textbooks concerned with Latin phonetics, namely that the Latin r was the so called alveolar trill or vibrant [r], such as e.g. the Italian r. The testimony of Latin authors is ambiguous: there is the evidence in support of this explanation, but also that testifying rather to the contrary. The sound changes related to the sound r in Latin afford evidence of the Latin r having indeed been alveolar, but more likely alveolar tap/flap than trill. Résumé L’article cherche à réunir les preuves que nous possédons pour la détermination du r latin en tant qu’une vibrante alvéolaire, ainsi que le r italien par exemple, une affirmation répétée dans des outils modernes traitant la phonétique latine. Les témoignages des auteurs antiques ne sont pas univoques : il y a des preuves qui soutiennent cette théorie, néanmoins d’autres tendent à la réfuter. Des changements phonétiques liés au phonème r démontrent que le r latin fut réellement alvéolaire, mais qu’il s’agissait plutôt d’une consonne battue que d’une vibrante. www.eruditio-antiqua.mom.fr LUCIE PULTROVÁ ON THE PHONETIC NATURE OF THE LATIN R The letter R of Latin alphabet denotes various phonetic entities generally called “rhotic consonants”. Some types of rhotic consonants are quite distant and it is not easy to define the one characteristic feature common to all rhotic consonants. -

The Diachronic Emergence of Retroflex Segments in Three Languages* 1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt am Main The diachronic emergence of retroflex segments in three languages* Silke Hamann ZAS (Centre for General Linguistics), Berlin [email protected] The present study shows that though retroflex segments can be considered articulatorily marked, there are perceptual reasons why languages introduce this class into their phoneme inventory. This observation is illustrated with the diachronic developments of retroflexes in Norwegian (North- Germanic), Nyawaygi (Australian) and Minto-Nenana (Athapaskan). The developments in these three languages are modelled in a perceptually oriented phonological theory, since traditional articulatorily-based features cannot deal with such processes. 1 Introduction Cross-linguistically, retroflexes occur relatively infrequently. From the 317 languages of the UPSI database (Maddieson 1984, 1986), only 8.5 % have a voiceless retroflex stop [ˇ], 7.3 % a voiced stop [Í], 5.3 % a voiceless retroflex fricative [ß], 0.9 % a voiced fricative [¸], and 5.9 % a retroflex nasal [˜]. Compared to other segmental classes that are considered infrequent, such as a palatal nasal [¯], which occurs in 33.7 % of the UPSID languages, and the uvular stop [q], which occurs in 14.8 % of the languages, the percentages for retroflexes are strikingly low. Furthermore, typically only large segment inventories have a retroflex class, i.e. at least another coronal segment (apical or laminal) is present, as in Sanskrit, Hindi, Norwegian, Swedish, and numerous Australian Aboriginal languages. Maddieson’s (1984) database includes only one exception to this general tendency, namely the Dravidian language Kota, which has a retroflex as its only coronal fricative. -

Arabic and English Consonants: a Phonetic and Phonological Investigation

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 6 No. 6; December 2015 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Arabic and English Consonants: A Phonetic and Phonological Investigation Mohammed Shariq College of Science and Arts, Methnab, Qassim University, Saudi Arabia E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.146 Received: 18/07/2015 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.146 Accepted: 15/09/2015 Abstract This paper is an attempt to investigate the actual pronunciation of the consonants of Arabic and English with the help of phonetic and phonological tools like manner of the articulation, point of articulation, and their distribution at different positions in Arabic and English words. A phonetic and phonological analysis of the consonants of Arabic and English can be useful in overcoming the hindrances that confront the Arab EFL learners. The larger aim is to bring about pedagogical changes that can go a long way in improving pronunciation and ensuring the occurrence of desirable learning outcomes. Keywords: Phonetics, Phonology, Pronunciation, Arabic Consonants, English Consonants, Manner of articulation, Point of articulation 1. Introduction Cannorn (1967) and Ekundare (1993) define phonetics as sounds which is the basis of human speech as an acoustic phenomenon. It has a source of vibration somewhere in the vocal apparatus. According to Varshney (1995), Phonetics is the scientific study of the production, transmission and reception of speech sounds. It studies the medium of spoken language. On the other hand, Phonology concerns itself with the evolution, analysis, arrangement and description of the phonemes or meaningful sounds of a language (Ramamurthi, 2004). -

THE INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET (Revised to 2015)

THE INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET (revised to 2015) CONSONANTS (PULMONIC) © 2015 IPA Bilabial Labiodental Dental Alveolar Postalveolar Retroflex Palatal Velar Uvular Pharyngeal Glottal Plosive Nasal Trill Tap or Flap Fricative Lateral fricative Approximant Lateral approximant Symbols to the right in a cell are voiced, to the left are voiceless. Shaded areas denote articulations judged impossible. CONSONANTS (NON-PULMONIC) VOWELS Clicks Voiced implosives Ejectives Front Central Back Close Bilabial Bilabial Examples: Dental Dental/alveolar Bilabial Close-mid (Post)alveolar Palatal Dental/alveolar Palatoalveolar Velar Velar Open-mid Alveolar lateral Uvular Alveolar fricative OTHER SYMBOLS Open Voiceless labial-velar fricative Alveolo-palatal fricatives Where symbols appear in pairs, the one to the right represents a rounded vowel. Voiced labial-velar approximant Voiced alveolar lateral flap Voiced labial-palatal approximant Simultaneous and SUPRASEGMENTALS Voiceless epiglottal fricative Primary stress Affricates and double articulations Voiced epiglottal fricative can be represented by two symbols Secondary stress joined by a tie bar if necessary. Epiglottal plosive Long Half-long DIACRITICS Some diacritics may be placed above a symbol with a descender, e.g. Extra-short Voiceless Breathy voiced Dental Minor (foot) group Voiced Creaky voiced Apical Major (intonation) group Aspirated Linguolabial Laminal Syllable break More rounded Labialized Nasalized Linking (absence of a break) Less rounded Palatalized Nasal release TONES AND WORD ACCENTS Advanced Velarized Lateral release LEVEL CONTOUR Extra Retracted Pharyngealized No audible release or high or Rising High Falling Centralized Velarized or pharyngealized High Mid rising Mid-centralized Raised ( = voiced alveolar fricative) Low Low rising Syllabic Lowered ( = voiced bilabial approximant) Extra Rising- low falling Non-syllabic Advanced Tongue Root Downstep Global rise Rhoticity Retracted Tongue Root Upstep Global fall Typeface: Doulos SIL . -

LING-001 Lecture 8: Phonetics

LING-001 Lecture 8: Phonetics Hilary Prichard 10/4/10 What is phonetics? The study of speech sounds From production to perception From Denes & Pinson, 1993 Three branches of phonetics Articulatory How speech is produced Acoustic Acoustic properties of speech Auditory How speech sounds are received and perceived Articulatory Phonetics How are speech sounds produced? The Vocal Tract The Larynx Contains the vocal folds (or cords) Air from the lungs passes through these folds When they are closed, the airflow causes them to vibrate The Vocal Folds in Action “Inside the Voice” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z_ZGqn1tZn8&feature=player_embedded “High Speed Video of the Vocal Folds” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9kHdhbEnhoA&feature=player_embedded The Articulators The parts of the vocal tract which are used to shape the sound Consonants Place of Articulation Which parts of the vocal tract are involved? Manner of Articulation What type of closure is created by the articulators? Place of Articulation Bilabial: made with both lips [p b m] Labiodental: made with lower lip and upper teeth [f v] Place of Articulation Dental: Tongue & upper front teeth [ð θ] Alveolar: Tongue & alveolar ridge [t d n s z] Place of Articulation Post-Alveolar: (palato-alveolar) Tongue & back of the alveolar ridge [∫ʒ] Palatal: Tongue & hard palate [j] Velar: Tongue & soft palate (velum) [k g ŋ] Manner of Articulation Stop: (plosive) complete closure, no air escapes through the mouth Oral Stop: Velum is raised; air cannot escape through the -

Introductory Phonology

9781405184120_1_pre.qxd 06/06/2008 09:47 AM Page iii Introductory Phonology Bruce Hayes A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405184120_4_C04.qxd 06/06/2008 09:50 AM Page 70 4 Features 4.1 Introduction to Features: Representations Feature theory is part of a general approach in cognitive science which hypo- thesizes formal representations of mental phenomena. A representation is an abstract formal object that characterizes the essential properties of a mental entity. To begin with an example, most readers of this book are familiar with the words and music of the song “Happy Birthday to You.” The question is: what is it that they know? Or, to put it very literally, what information is embodied in their neurons that distinguishes a knower of “Happy Birthday” from a hypothetical person who is identical in every other respect but does not know the song? Much of this knowledge must be abstract. People can recognize “Happy Birth- day” when it is sung in a novel key, or by an unfamiliar voice, or using a different tempo or form of musical expression. Somehow, they can ignore (or cope in some other way with) inessential traits and attend to the essential ones. The latter include the linguistic text, the (relative) pitch sequences of the notes, the relative note dura- tions, and the musical harmonies that (often tacitly) accompany the tune. Cognitive science posits that humans possess mental representations, that is, formal mental objects depicting the structure of things we know or do. A typical claim is that we are capable of singing “Happy Birthday” because we have (during childhood) internalized a mental representation, fairly abstract in character, that embodies the structure of this song. -

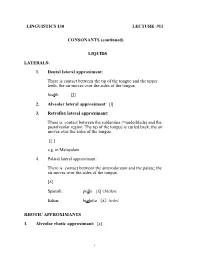

1. Dental Lateral Approximant: There Is Contact Between the Tip of the Tongue and the Upper Teeth; the Air Moves Over the Sides of the Tongue

LINGUISTICS 130 LECTURE #11 CONSONANTS (continued) LIQUIDS LATERALS: 1. Dental lateral approximant: There is contact between the tip of the tongue and the upper teeth; the air moves over the sides of the tongue. health [l∞] 2. Alveolar lateral approximant: [l] 3. Retroflex lateral approximant: There is contact between the sublamina (=underblade) and the postalveolar region. The tip of the tongue is curled back; the air moves over the sides of the tongue. [Æ ] e.g. in Malayalam 4. Palatal lateral approximant: There is contact between the anterodorsum and the palate; the air moves over the sides of the tongue. [Ò] Spanish: pollo [Ò] chicken Italian: bigletto [Ò] ticket RHOTIC APPROXIMANTS 1. Alveolar rhotic approximant: [®] 1 2. Retroflex rhotic approximant: The sublamina approximates the postalveolar region while the tip of the tongue is curled back. [ï] FLAPS The active articulator (tip of the tongue) strikes the place of articulation, and after momentary contact it immediately withdraws. MOMENTARY CONTACT BETWEEN TWO ARTICULATORS! Alveolar flaps: the tip of the tongue makes momentary contact with the alveolar ridge. Common in North American English: [‰] alveolar flap (voiced) Betty, writer, rider [‰] TRILLS One articulator is held loosely near to another so that the flow of air between them sets one of the articulators (e.g. the tongue) in motion, alternately sucking them together and blowing them apart. There are usually three vibrating movements in a typical trill. 1. Alveolar trill: apex articulators alveolar ridge [r] (voiced) Finnish: raha [r] money 2 2. Uvular trill: dorsum articulators uvula [R] (voiced) It occurs in some varieties of French instead of the uvular fricative. -

The Phonetics and Phonology of Retroflexes Published By

The Phonetics and Phonology of Retroflexes Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6006 Trans 10 fax: +31 30 253 6000 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://wwwlot.let.uu.nl/ Cover illustration by Silke Hamann ISBN 90-76864-39-X NUR 632 Copyright © 2003 Silke Hamann. All rights reserved. The Phonetics and Phonology of Retroflexes Fonetiek en fonologie van retroflexen (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, Prof. Dr. W.H. Gispen, ingevolge het besluit van het College voor Promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 6 juni 2003 des middags te 4.15 uur door Silke Renate Hamann geboren op 25 februari 1971 te Lampertheim, Duitsland Promotoren: Prof. dr. T. A. Hall (Leipzig University) Prof. dr. Wim Zonneveld (Utrecht University) Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Markedness of retroflexes 3 1.2 Phonetic cues and phonological features 6 1.3 Outline of the dissertation 8 Part I: Phonetics of Retroflexes 2 Articulatory variation and common properties of retroflexes 11 2.1 Phonetic terminology 12 2.2 Parameters of articulatory variation 14 2.2.1 Speaker dependency 15 2.2.2 Vowel context 16 2.2.3 Speech rate 17 2.2.4 Manner dependency 19 2.2.4.1 Plosives 19 2.2.4.2 Nasals 20 2.2.4.3 Fricatives 21 2.2.4.4 Affricates 23 2.2.4.5 Laterals 24 2.2.4.6 Rhotics 25 2.2.4.7 Retroflex vowels 26 2.2.5 Language family 27 2.2.6 Iventory size 28 2.3 Common articulatory properties of retroflexion 32 2.3.1 Apicality 33 2.3.2 Posteriority -

LIN 3201 Sounds of Human Language Manual by Ratree

LIN 3201 Sounds of Human Language Manual By Ratree Wayland Program in Linguistics University of Florida Gainesville, FL 2 Introduction There are approximately 7,000 languages in the world, and the sounds employed by these languages show both similarities and differences. Thus, an interesting question that one might ask is, “What factors affect the sounds a language can or cannot use?” First of all, we are constrained by what we can do with our tongue, our lips and other organs involved in the production of speech sounds. This factor may be referred to as the ‘articulatory ease’ factor. Secondly, we are constrained by what we can hear or what we can perceptually distinguish. This is the ‘auditory distinctiveness’ factor. Thus, no language in the world has sounds that are too difficult for native speakers to produce or to perceptually differentiate. To nonnative speakers, however, certain sounds may prove challenging to both produce and perceive. One of the goals of this course is to familiarize students with the various sounds employed in the world’s languages. Students will learn how to describe, produce and perceptually distinguish these sounds. Describing Speech Sounds Phonetics is concerned with describing speech sounds that occur in the world’s languages. Speech sounds can be described in at least two different ways. First we can describe them in terms of how they are made in the vocal tract (articulatory phonetics). As speech sounds leave the mouth, they cause disturbances in the surrounding air (sound waves). Thus, another way that we can describe speech sound is to analyze its acoustic sound wave (acoustic 3 phonetics). -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Deriving Natural Classes: The Phonology and Typology of Post-velar Consonants Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/50v3m3g6 Author Sylak-Glassman, John Publication Date 2014 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Deriving Natural Classes: The Phonology and Typology of Post-Velar Consonants by John Christopher Sylak-Glassman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Sharon Inkelas, Chair Professor Andrew Garrett Professor Keith Johnson Professor Darya Kavitskaya Spring 2014 Deriving Natural Classes: The Phonology and Typology of Post-Velar Consonants Copyright 2014 by John Christopher Sylak-Glassman 1 Abstract Deriving Natural Classes: The Phonology and Typology of Post-Velar Consonants by John Christopher Sylak-Glassman Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Sharon Inkelas, Chair In this dissertation, I propose a new method of deriving natural classes that is motivated by the phonological patterning of post-velar consonants (uvulars, pharyngeals, epiglottals, and glot- tals). These data come from a survey of the phonemic inventories, phonological processes, and distributional constraints in 291 languages. The post-velar consonants have been claimed to constitute an innate natural class, the gutturals (McCarthy 1994). However, no single phonetic property has been shown to characterize every post-velar consonant. Using data from P-base (Mielke 2008), I show that the phonological pat- terning of the post-velar consonants is conditioned by the presence of a pharyngeal consonant, and argue more generally that natural classes can be derived from phonetic connections that link spe- cific subsets of phonemes. -

Retroflexion: an Areal Feature. Working Papers on Language Universals, No

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 105 719 FL 006 324 AUTHOR Bhat, D.N.S. TITLE Retroflexion: An Areal Feature. Working Papers on Language Universals, No. 13. INSTITUTION Stanford Univ., Calif. Committee on Linguistics. PUB DATE Dec 73 NOTE 43p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$1.95 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Articulation (Speech); Consonants; *Diachronic Linguistics; Distinctive Features; *Language Universals; Language Variation; Phonemics; *Phonetics; *Phonology; Pronunciation; Uncommonly Taught Languages; Vowels IDENTIFIERS *Retroflexion ABSTRACT The phenomenon of retroflexion is discussed, and its occurrence in about 150 selected languages is examined from a geographical and a diachronic point of view. The clustering of such languages into distinct areas has been explained through the postulation of a hypothesis regarding their development in language. After a detailed examination of four different areas of retroflexion, their known history, and the present position of retroflexion in them, an attempt is made to generalize the environments that induce retroflexion in a given sound, and also to postulate developmental tendencies. Lastly, the place of retroflexion isa system of phonics is explained. (Author/AM) Working Papers on Language Universals No. 13, December 1973 pp. 27- 67 RETROFLEXI011.: AN AREAL FEATURE D.N.S. That Language Universals Project, and Deccan College, Poona ABSTRACT The occurrence of retroflexion in about 150 selected languages is examined in this paper from a geographical and a diachronic point of view. The clustering of such languages into distinct areas has been explained through the postulation of a hypothesis regarding their devel- opment in language. After a detailed examination of four different areas of retroflexion, their known history, and the present position of retroflexion in them, an attempt is made to generalize the environ- ments that induce retroflexion in a given sound, and also to postulate developmental tendencies.Lastly, the place of retroflexion in a system of phonetics is explained.