Efiner Testing the Boundaries Lev Lunts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zitierhinweis Copyright Kargol, Tomasz: Rezension Über: Paulus

Zitierhinweis Kargol, Tomasz: Rezension über: Paulus Adelsgruber / Laurie Cohen / Börries Kuzmany, Getrennt und doch verbunden. Grenzstädte zwischen Österreich und Russland 1772-1918, Wien: Böhlau, 2011, in: Český časopis historický, 2014, 1, S. 128-131, DOI: 10.15463/rec.1189726940 First published: Český časopis historický, 2014, 1 copyright Dieser Beitrag kann vom Nutzer zu eigenen nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken heruntergeladen und/oder ausgedruckt werden. Darüber hinaus gehende Nutzungen sind ohne weitere Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber nur im Rahmen der gesetzlichen Schrankenbestimmungen (§§ 44a-63a UrhG) zulässig. Recenzovaná práce tedy evidentně přináší nejen mnoho nových a zajímavých zjištění o poddanské tematice, učiněných na základě aplikace zatím ne zcela běžné badatelské perspekti- vy, ale nabízí i řadu východisek pro navazující studie. Jan Horský Paulus ADELSGRUBER – Laurie COHEN – Börries KUZMANY Getrennt und doch verbunden. Grenzstädte zwischen Österreich und Russland 1772–1918 Wien-Köln-Weimar, Böhlau Verlag 2011, 316 pp., ISBN 978-3-205-78625-2. The reviewed publication was created within two research projects that is: „Multikulturel- le Grenzstädte in der Westukraine 1772–1914” (Multi-cultural border towns in the Western Ukraine in the years 1772–1914) and „Imperiale Peripherien: Religion, Krieg und die Szlach- ta” (Imperial outskirts: religion, war and the szlachta). Those projects were realised in the years 2004–2009 by Institut für Osteuropäische Geschichte of the Vienna University under the di- rection of Andreas Kappeler, including the authors of the reviewed publication – Laurie Cohen, Paulus Adelsgruber and Boeries Kuzmany. The book however is not a collection of articles by various authors but a collective monograph. The monograph „Getrennt und doch verbunden“ corresponds with the research trends of the Department of East Europe History and the interests of its authors. -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

Paulus Adelsgruber / Laurie Cohen / Bör Ries Kuzmany, Getrennt Und Do

Zitierhinweis Kargol, Tomasz: Rezension über: Paulus Adelsgruber / Laurie Cohen / Börries Kuzmany, Getrennt und doch verbunden. Grenzstädte zwischen Österreich und Russland 1772-1918, Wien: Böhlau, 2011, in: Český časopis historický, 2014, 1, S. 128-131, http://recensio.net/r/a4cf296091704c57aec49b6f19eb3bb0 First published: Český časopis historický, 2014, 1 copyright Dieser Beitrag kann vom Nutzer zu eigenen nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken heruntergeladen und/oder ausgedruckt werden. Darüber hinaus gehende Nutzungen sind ohne weitere Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber nur im Rahmen der gesetzlichen Schrankenbestimmungen (§§ 44a-63a UrhG) zulässig. Recenzovaná práce tedy evidentně přináší nejen mnoho nových a zajímavých zjištění o poddanské tematice, učiněných na základě aplikace zatím ne zcela běžné badatelské perspekti- vy, ale nabízí i řadu východisek pro navazující studie. Jan Horský Paulus ADELSGRUBER – Laurie COHEN – Börries KUZMANY Getrennt und doch verbunden. Grenzstädte zwischen Österreich und Russland 1772–1918 Wien-Köln-Weimar, Böhlau Verlag 2011, 316 pp., ISBN 978-3-205-78625-2. The reviewed publication was created within two research projects that is: „Multikulturel- le Grenzstädte in der Westukraine 1772–1914” (Multi-cultural border towns in the Western Ukraine in the years 1772–1914) and „Imperiale Peripherien: Religion, Krieg und die Szlach- ta” (Imperial outskirts: religion, war and the szlachta). Those projects were realised in the years 2004–2009 by Institut für Osteuropäische Geschichte of the Vienna University under the di- rection of Andreas Kappeler, including the authors of the reviewed publication – Laurie Cohen, Paulus Adelsgruber and Boeries Kuzmany. The book however is not a collection of articles by various authors but a collective monograph. The monograph „Getrennt und doch verbunden“ corresponds with the research trends of the Department of East Europe History and the interests of its authors. -

New Information About Attack on Vitrenko Appears to Reveal A

INSIDE:• Ukraine’s elections: between the Russian and Belarusian scenarios — page 6. • Hundreds of international observers arrive for the elections — page 8. • Journey to a recovered memory in Volochysk — page 9. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXVII HE No.KRAINIAN 44 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, OCTOBER 31, 1999 EEKLY$1.25/$2 in Ukraine NewT information aboutU attack on Vitrenko Kaniv Four disintegratesW as coalition appears to reveal a surprising conspiracy cannot agree on a single candidate by Roman Woronowycz an permission to do so. by Roman Woronowycz explained Mr. Tkachenko. “Our plans to Kyiv Press Bureau Mr. Mitrofanov explained that he had Kyiv Press Bureau mobilize the electorate have failed. In this been prepared to have a handwriting analy- situation, there is no sense in continuing to KYIV – The investigation of the October sis done of the note to ascertain its authen- KYIV – Unable to agree on who among pursue our main task.” 2 grenade attack on presidential candidate ticity, but will wait until the same Ukrainian them should be their single presidential can- He drew gasps and shouts from journal- Natalia Vitrenko took on a new dimension officials conduct their own analysis, which didate, the Kaniv Four political alliance dis- ists when he made another unexpected dec- on October 21 when a Russian parliamen- he said would occur after the October 31 integrated on October 26, with each candi- laration: that he had agreed in talks with Mr. tary hearing revealed that Ms. Vitrenko’s presidential elections. date going his own way, and Oleksander Symonenko to withdraw his own candidacy own people might have been involved in The State Security Service of Ukraine Tkachenko announcing that he had aligned in favor of the Communist Party candidate. -

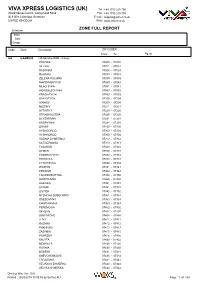

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA -

Buy Ternopil Product» CLOSE JOINT-STOCK COMPANY «POTUTORSKYI WOODWORKING FACTORY»

CATALOGUE «Buy Ternopil Product» CLOSE JOINT-STOCK COMPANY «POTUTORSKYI WOODWORKING FACTORY» Director: Kostiuk Vadym tel./fax: (03548) 3-42-47, 3-60-52; mob.: 0673545869 Domicile: 47533, Ternopil region, Berezhany district, Saranchuky village Place of production: 47533, Berezhany district, Saranchuky village Type of business: sawing and planing manufacture KVED (Classification of Business): 20.10.0 DSTU (State Standard of Ukraine): 3819-98 Basic assortment: - fake parquet - wooden linings - producing wooden linings - producing wooden platbands - producing parquet - joinery production - parquet frieze purchase - wooden platbands LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY «PIDVYSOTSKYI FACTORY OF BUILDING MATERIALS» Director: Vereshchaka Volodymyr tel.: (03548) 3-60-12, 3-21-43 Domicile: 47523, Ternopil region, Berezhany district, Pidvysoke village Place of production: 47523, Ternopil region, Berezhany district, Pidvysoke village Type of business: production of lime KVED (Classification of Business): 26.52.0 DSTU (State Standard of Ukraine): B.V.2.7.-90-99 Basic assortment: - construction lime - limestone flux - limestone flux powder - sand CATERING COMPANY RAYST OF BEREZHANY Director: Koval Olga tel.: (03548) 2-13-76, 2-17-58, 2-27-88 Domicile: 47500, Ternopil region, Berezhany district, Berezhany town, 26 Rynok Square Place of production: 47500, Ternopil region, Berezhany district, Berezhany town, 136 Shevchenka Str. Type of business: panification and bakery KVED (Classification of Business): 15.81.0 DSTU (State Standard of Ukraine): GOST 28808-90 Basic -

Catalogue of Competitive Indust

2 PRIVATE ENTERPRISE “FLYUK” Director: Galina Peretska Tel.: +38 (03548) 2 12 85 Registered address: 47501, Berezhany district, Berezhany, 6, Zolochivska str. Activity: Baking bread and bakery products E-mail: [email protected] Basic range of products: Bread and bakery products LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY "KRONA" Director: Stepan Leshchuk Tel.: +38 (03548) 3 82 88 Registered address: Ternopil oblast, Berezhany district, Zhukiv village, 1, Zolochivska str. Activity: Manufacture of canned products E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.kronafoods.com/ Basic range of products: Green peas, cucumbers PRIVATE ENTERPRISE “AGROSPETSGOSP” Director: Igor Kotovskyy Tel.: +38 ( 03548) 3 60 16 Registered address: Ternopil oblast, Ternopil region, Plotycha village Activity: production of canned products E-mail: [email protected] Basic range of products: fruit and vegetable juices, canned vegetables, fruits with vinegar LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY "PIDVYSOTSKYJ PLANT MATERIALS" Director: Volodymyr Vereshchaka Tel.: +38 (03548) 3-60-12 Registered address: 47500, Ternopil oblast Berezhany district, Pidvysoke village 3 Activity: Production of lime E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.pzbm.com.ua Basic range of products: Lime, sand, limestone LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY "KHRYSTYNA" Director: Volodymyr Fedchyshyn Tel.: +38 (03548) 2-57-39 Registered address: Ternopil oblast, Berezhany,4, Zamost str. Activity: Manufacture of corrugated packaging E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.chrystyna.com.ua Basic range of products: Corrugated boxes of different sizes LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY "POTUTORSKYI WOODWORKING FACTORY" Director: Vadym Kostyuk Tel.: +38 (03548) 3-42-47, 3-42-37 Registered address: 47533, Ternopil oblast, Berezhany district, Saranchuky village Activity: Manufacture of block parquet E-mail: [email protected] Basic range of products: Plank parquet of temperate hardwood LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY "SANZA-TOP" Director: Nemesio Chavez Gonzalez Tel.: +38 (03548) 2 18 67 Registered address: 47501, Ternopil oblast, Berezhany, 69, Sichovykh Striltsiv Str. -

Important Plant Areas of Ukraine

Important Plant Areas of Ukraine Editor: V.A. Onyshchenko പ ˄ʪʶϱϬϮ͘ϳϱ;ϰϳϳͿ ʦϭϮ ^ĞůĞĐƟŽŶĐƌŝƚĞƌŝĂ Important Plant Areas of Ukraine / V.A. Onyshchenko (editor). – Kyiv: Alterpress, 2017. – 376 p. dŚĞŬĐŽŶƚĂŝŶƐĚĞƐĐƌŝƉƟŽŶƐŽĨϭϳϯ/ŵƉŽƌƚĂŶƚWůĂŶƚƌĞĂƐŽĨhŬƌĂŝŶĞ͘ĂƚĂŽŶĞĂĐŚƐŝƚĞ dŚĞĂŝŵŽĨƚŚĞ/ŵƉŽƌƚĂŶƚWůĂŶƚƌĞĂƐ;/WƐͿƉƌŽŐƌĂŵŵĞŝƐƚŽŝĚĞŶƟĨLJĂŶĚƉƌŽƚĞĐƚ ŝŶĐůƵĚĞŝƚƐĂƌĞĂ͕ŐĞŽŐƌĂƉŚŝĐĂůĐŽŽƌĚŝŶĂƚĞƐ͕ƐĞůĞĐƟŽŶĐƌŝƚĞƌŝĂ͕ĂƌĞĂƐŽĨhE/^ŚĂďŝƚĂƚƚLJƉĞƐ͕ ĂŶĞƚǁŽƌŬŽĨƚŚĞďĞƐƚƐŝƚĞƐĨŽƌƉůĂŶƚĐŽŶƐĞƌǀĂƟŽŶƚŚƌŽƵŐŚŽƵƚƵƌŽƉĞĂŶĚƚŚĞƌĞƐƚŽĨƚŚĞ ĐŚĂƌĂĐƚĞƌŝnjĂƟŽŶŽĨǀĞŐĞƚĂƟŽŶ͕ƚŚƌĞĂƚƐ͕ŚƵŵĂŶĂĐƟǀŝƟĞƐ͕ŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶĂďŽƵƚƉƌŽƚĞĐƚĞĚĂƌͲ ǁŽƌůĚ͕ ƵƐŝŶŐ ĐŽŶƐŝƐƚĞŶƚ ĐƌŝƚĞƌŝĂ ;ŶĚĞƌƐŽŶ͕ ϮϬϬϮͿ͘ dŚĞ ŝĚĞŶƟĮĐĂƟŽŶ ŽĨ /WƐ ŝƐ ďĂƐĞĚ ŽŶ ĞĂƐ͕ƌĞĨĞƌĞŶĐĞƐ͕ĂŶĚĂŵĂƉŽŶƚŚĞƐĂƩĞůŝƚĞŝŵĂŐĞďĂĐŬŐƌŽƵŶĚ͘ ƚŚƌĞĞĐƌŝƚĞƌŝĂ͘ƌŝƚĞƌŝŽŶʹWƌĞƐĞŶĐĞŽĨƚŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚƉůĂŶƚƐƉĞĐŝĞƐ͗ƚŚĞƐŝƚĞŚŽůĚƐƐŝŐŶŝĮĐĂŶƚ ƉŽƉƵůĂƟŽŶƐŽĨŽŶĞŽƌŵŽƌĞƐƉĞĐŝĞƐƚŚĂƚĂƌĞŽĨŐůŽďĂůŽƌƌĞŐŝŽŶĂůĐŽŶƐĞƌǀĂƟŽŶĐŽŶĐĞƌŶ͘ ʦ̸̨̛̙̣̞̯̦̞̦̞̌̏̍̌ ̨̛̯̖̬̯̬̞̟˄̡̛̬̟̦̌ͬ ̬̖̌̔̚͘ ʦ͘ʤ͘ ʽ̡̛̦̺̖̦̌͘ ʹ ʶ̛̟̏͗ ʤ̣̯̖̬̪̬̖̭͕̽ ƌŝƚĞƌŝŽŶʹWƌĞƐĞŶĐĞŽĨďŽƚĂŶŝĐĂůƌŝĐŚŶĞƐƐ͗ƚŚĞƐŝƚĞŚĂƐĂŶĞdžĐĞƉƟŽŶĂůůLJƌŝĐŚŇŽƌĂŝŶĂ ϮϬϭϳ͘ʹϯϳϲ̭͘ ƌĞŐŝŽŶĂůĐŽŶƚĞdžƚŝŶƌĞůĂƟŽŶƚŽŝƚƐďŝŽŐĞŽŐƌĂƉŚŝĐnjŽŶĞ͘ƌŝƚĞƌŝŽŶʹWƌĞƐĞŶĐĞŽĨƚŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚ /^EϵϳϴͲϵϲϲͲϱϰϮͲϲϮϮͲϲ ŚĂďŝƚĂƚƐ͗ƚŚĞƐŝƚĞŝƐĂŶŽƵƚƐƚĂŶĚŝŶŐĞdžĂŵƉůĞŽĨĂŚĂďŝƚĂƚŽƌ ǀĞŐĞƚĂƟŽŶƚLJƉĞŽĨŐůŽďĂůŽƌ ʶ̛̦̐̌ ̛̥̞̭̯̯̽ ̨̛̛̪̭ ϭϳϯ ʦ̵̛̛̙̣̌̏ ̸̵̨̛̯̦̞̦̍̌ ̨̛̯̖̬̯̬̞̜ ˄̡̛̬̟̦̌͘ ʪ̦̞̌ ̨̪̬ ̡̨̙̦̱ ƌĞŐŝŽŶĂůƉůĂŶƚĐŽŶƐĞƌǀĂƟŽŶĂŶĚďŽƚĂŶŝĐĂůŝŵƉŽƌƚĂŶĐĞ͘Η/WΗŝƐŶŽƚĂŶŽĸĐŝĂůĚĞƐŝŐŶĂƟŽŶ͘ ̨̛̯̖̬̯̬̞̀ ̸̡̣̯̏̀̌̀̽ ̟̟ ̨̪̣̺̱͕ ̴̸̨̖̬̞̦̞̐̐̌ ̡̨̨̛̛̬̦̯͕̔̌ ̡̛̬̯̖̬̞̟ ̛̞̣̖̦̦͕̏̔́ ̨̪̣̺̞ /WƐĂƌĞƐĞůĞĐƚĞĚƐĐŝĞŶƟĮĐĂůůLJƵƐŝŶŐĐƌŝƚĞƌŝĂƐƵƉƉŽƌƚĞĚďLJĞdžƉĞƌƚƐĐŝĞŶƟĮĐũƵĚŐĞŵĞŶƚ͘ ̴̶̨̡̡̛̛̭̖̣̺̣̭̞̞̌̌̌̿̀̚hE/^̵̡̡̨̨̨̡̨̛̛̛̛̛̛͕̬̯̖̬̭̯̱̬̭̣̦̦̭̯̞͕̬͕̣̭̟̌̌̌̐̏̔̀̔̽̚̚ -

Appendix 4 to the SSUFSCP Letter

List of Storage Facilities from which barley Exports to the People’s Republic of China are Planned No. Full Name Legal Address Storage Address Vinnytsia region 1. Limited Liability Company 23100 23100 “ZHMERINSKY ELEVATOR” Ukraine, Ukraine, Vinnitsa region, Vinnitsa region, Zhmerynka, Zhmerynka, Chernishevskogo str.42 Chernishevskogo str.42 2. Branch "Khmilnitsky elevator" ADM 22000, 22000, Ukraine LLC" Ukraine, Ukraine, Vinnytsia region, Vinnytsia region, Khmilnyk, Khmilnyk, 26, Basylya Poryka street 26, Basylya Poryka street Volyns`ka region 3. LLC ‘Pyatydni’ 44730, 44730, Ukraine, Ukraine, Volyn region, Volyn region, Volodymyr-Volynsky district, city Ustilug v Pyatydni, street Independence, 56 Dnipropetrovsk region 4. Branch “Dnipropetrovsk River Port” 49021, 49021, JSSK “UKRRICHFLOT” Ukraine, Ukraine, Dnipro, Dnipro, 11, Amur-Gavan`street 11, Amur-Gavan`street 5. Limited Liability Company 49021, 49021, "GRAIN TRANSSHIPMENT" Ukraine, Ukraine, Dnipro, Dnipro, 102, Marshal Malinowski street, 102, Marshal Malinowski street, building D building D 6. Borivaje Limited Liability Company 49006, 67550, Ukraine, Ukraine, Dnipropetrovsk region, Odesa region, Dnipro, Limanskiy district, Pushkin avenue, 4 Novi Biliari, 10 Industrialna Str. Zhytomyr region 7. Limited Liability Company "Berdychiv- 10001 13300, Zerno" Ukraine, Ukraine, Zhytomyr, Zhytomyr oblast, 85A Serhiy Paradzhanov st Berdychiv, 84 Zhytomyrska st, Kyiv region 8. “AIK TRADING” LLC 01133, 31000, Ukraine, Ukraine, Kyiv, Khmelnytsk region, 18/7 V, Henerala Almazova street Krasyliv, 150, Hrushevskogo street 9. Limited liability Company “Ukrainian 04073, 20753, Elevator Company” (Serdiukivka Grain Ukraine, Ukraine, Warehouse)/ “UKRELCO” LLC Kyiv, Cherkas y region, 1-A, Sportyvna square, Smilyans`kyj district, BC “Gulliver”, village Serdiukivka, 15 floor Zaliznychna street, 1 10. Branch of JSC “SFGCU” 01033, 54034, “Mykolaivskyi port elevator” Ukraine, Ukraine, Kyiv, Mykolaiv, 1, Saksahanskoho street 122/1 Persha slobidska street 11. -

GEOLEV2 Label Updated October 2020

Updated October 2020 GEOLEV2 Label 32002001 City of Buenos Aires [Department: Argentina] 32006001 La Plata [Department: Argentina] 32006002 General Pueyrredón [Department: Argentina] 32006003 Pilar [Department: Argentina] 32006004 Bahía Blanca [Department: Argentina] 32006005 Escobar [Department: Argentina] 32006006 San Nicolás [Department: Argentina] 32006007 Tandil [Department: Argentina] 32006008 Zárate [Department: Argentina] 32006009 Olavarría [Department: Argentina] 32006010 Pergamino [Department: Argentina] 32006011 Luján [Department: Argentina] 32006012 Campana [Department: Argentina] 32006013 Necochea [Department: Argentina] 32006014 Junín [Department: Argentina] 32006015 Berisso [Department: Argentina] 32006016 General Rodríguez [Department: Argentina] 32006017 Presidente Perón, San Vicente [Department: Argentina] 32006018 General Lavalle, La Costa [Department: Argentina] 32006019 Azul [Department: Argentina] 32006020 Chivilcoy [Department: Argentina] 32006021 Mercedes [Department: Argentina] 32006022 Balcarce, Lobería [Department: Argentina] 32006023 Coronel de Marine L. Rosales [Department: Argentina] 32006024 General Viamonte, Lincoln [Department: Argentina] 32006025 Chascomus, Magdalena, Punta Indio [Department: Argentina] 32006026 Alberti, Roque Pérez, 25 de Mayo [Department: Argentina] 32006027 San Pedro [Department: Argentina] 32006028 Tres Arroyos [Department: Argentina] 32006029 Ensenada [Department: Argentina] 32006030 Bolívar, General Alvear, Tapalqué [Department: Argentina] 32006031 Cañuelas [Department: Argentina] -

Lars Westerlund, the Finnish SS-Volunteers and Atrocities

LARS WESTERLUND The Finnish SS-VOLUNTEERS AND ATROCITIES 1941–1943 SKS The Finnish SS-VOLUNTEERS AND ATROCITIES 1941–1943 LARS WESTERLUND THE FINNISH SS-VOLUNTEERS AND ATROCITIES against Jews, Civilians and Prisoners of War in Ukraine and the Caucasus Region 1941–1943 An Archival Survey Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura – Finnish Literature Society Kansallisarkisto – The National Archives of Finland Helsinki 2019 Steering Group Permanent State Under-Secretary Timo Lankinen, Prime Minister’s Office / Chair Research Director Päivi Happonen, The National Archives of Finland Director General Jussi Nuorteva, The National Archives of Finland Legal Adviser Päivi Pietarinen, Office of the President of the Republic of Finland Production Manager, Tiina-Kaisa Laakso-Liukkonen, Prime Minister’s Office / Secretary Project Group Director General Jussi Nuorteva, The National Archives of Finland / Chair Research Director Päivi Happonen, The National Archives of Finland / Vice-Chair Associate Professor Antero Holmila, University of Jyväskylä Dean of the Faculty of Law, Professor Pia Letto-Vanamo, University of Helsinki Professor Kimmo Rentola, University of Helsinki Academy Research Fellow Oula Silvennoinen, University of Helsinki Docent André Swanström, Åbo Akademi University Professor, Major General Vesa Tynkkynen, The National Defence University Professor Lars Westerlund Researcher Ville-Pekka Kääriäinen, The National Archives of Finland / Secretary Publisher’s Editor Katri Maasalo, Finnish Literature Society (SKS) Proofreading and translations William Moore Maps Spatio Oy Graphic designer Anne Kaikkonen, Timangi Cover: Finnish Waffen-SS troops ready to start the march to the East in May or early June 1941. OW Coll. © 2019 The National Archives of Finland and Finnish Literature Society (SKS) Kirjokansi 222 ISBN 978-951-858-111-9 ISSN 2323-7392 Kansallisarkiston toimituksia 22 ISSN 0355-1768 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License. -

Ukrainian Orthodox Center Inundated by Irene's Floodwaters Tabachnyk

INSIDE: l Miss Soyuzivka 2012 is crowned – page 4 l Communities mark Ukrainian Independence Day – page 13 l Update on excavations at Baturyn – pages 14-15 HEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit associationEEKLY T W Vol. LXXIX No. 36 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 4, 2011 $1/$2 in Ukraine Tabachnyk will be dismissed, World Forum of Ukrainians concludes, says Presidential Administration chief elects Mykhailo Ratushny as president KYIV – The fifth World Forum of the forum participants, “I know how much Ukrainians concluded in Kyiv on August effort you have put in Ukraine becoming An editorial cartoon 21, electing veteran political and social independent. It is our common grand cele by Anatoliy Petrovich activist Mykhailo Ratushny, a native of bration.” He added, “I would like you to Vasilenko was pub Ternopil, Ukraine, as its new president. know that not only do I know well your lished in the Kyiv Post The Ukrainian World Coordinating concerns and your aspirations, but I will soon after Dmytro Council (UWCC) gathering assembled also do everything that you will have no Tabachnyk was 300 delegates – 100 from Ukraine, 100 worries about Ukraine and its future.” appointed on March from the Eastern Diaspora and 100 from In his message the president said he 11, 2010, as minister of the Western Diaspora – for three days of had recently submitted a bill on education and science. meetings in the Ukrainian capital begin- Ukrainians living abroad to the It is reprinted with ning on August 19. Verkhovna Rada, identifying it as urgent, permission from the The delegates were addressed in the and has also decided to establish a sepa- Kyiv Post.