Edvard Grieg's Orchestral Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grieg & Musical Life in England

Grieg & Musical Life in England LIONEL CARLEY There were, I would prop ose, four cornerstones in Grieg's relationship with English musicallife. The first had been laid long before his work had become familiar to English audiences, and the last was only set in place shortly before his death. My cornerstones are a metaphor for four very diverse and, you might well say, ve ry un-English people: a Bohemian viol inist, a Russian violinist, a composer of German parentage, and an Australian pianist. Were we to take a snapshot of May 1906, when Grieg was last in England, we would find Wilma Neruda, Adolf Brodsky and Percy Grainger all established as significant figures in English musicallife. Frederick Delius, on the other hand, the only one of thi s foursome who had actually been born in England, had long since left the country. These, then, were the four major musical personalities, each having his or her individual and intimate connexion with England, with whom Grieg established lasting friendships. There were, of course, others who com prised - if I may continue and then finally lay to rest my architectural metaphor - major building blocks in the Grieg/England edifice. But this secondary group, people like Francesco Berger, George Augener, Stop ford Augustus Brooke, for all their undoubted human charms, were firs t and foremost representatives of British institutions which in their own turn played an important role in Grieg's life: the musical establishment, publishing, and, perhaps unexpectedly religion. Francesco Berger (1834-1933) was Secretary of the Philharmonic Soci ety between 1884 and 1911, and it was the Philharmonic that had first prevailed upon the mature Grieg to come to London - in May 1888 - and to perform some of his own works in the capital. -

Peer Gynt: Suite No. 1 Instrumentation: Piccolo, 2 Flutes, 2 Oboes, 2

Peer Gynt: Suite No. 1 Instrumentation: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, strings. Duration: 15 minutes in four movements. THE COMPOSER – EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907) – Grieg spent much of the 1870s collaborating with famous countrymen authors. With Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson, the composer had hoped to mount a grand operatic history of King Olav Tryggvason but the two artists soon ran afoul of one another. A possible contributing factor was Grieg’s moonlighting project with Henrik Ibsen but, in truth, Bjørnson and the composer had been nursing hurt feelings for a while by the time the latter began to stray. THE MUSIC – As it turned out, Grieg’s back-up plan was more challenging than rewarding at first. He was to compose incidental music that expanded and stitched together the sections of Ibsen’s epic poem. This he did with delight, but soon found the restrictions of the theatrical setting more a burden than a help creatively. “In no case,” he claimed, “had I opportunity to write as I wanted” but the 1876 premiere was a huge success regardless. Grieg seized the chance to re-work some of the music and add new segments during the 1885 revival and did the same in 1902. The two suites he published in 1888 and 1893 likely represent his most ardent hopes for his part of the project and stand today as some of his most potently memorable work. Ibsen’s play depicted the globetrotting rise and fall of a highly symbolic Norwegian anti-hero and, in spite of all the aforementioned struggles, the author could not have chosen a better partner than Grieg to enhance the words with sound. -

Beyond the Storm

Pamela J. Marshall Beyond the Storm oboe collection of Poetry-Inspired Solos PREVIEWSpindrift Music Company www.spindrift.com Publishing contemporary classical music and promoting its performance and appreciation collection of Poetry-Inspired Solos Beyond the Storm by Pamela J. Marshall for oboe La Mer by Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) From Poems, 1881 A white mist drifts across the shrouds, A wild moon in this wintry sky Gleams like an angry lion's eye Out of a mane of tawny clouds. The muffled steersman at the wheel Is but a shadow in the gloom;-- And in the throbbing engine-room Leap the long rods of polished steel. The shattered storm has left its trace Upon this huge and heaving dome, For the thin threads of yellow foam Float on the waves like ravelled lace. PREVIEWSpindrift Music Company www.spindrift.com aer "La Mer" by Oscar Wilde Beyond the Storm Pamela J. Marshall Andante misterioso, con licenza q = 86 Oboe p p mp pp mp pp 2 p pp mp 4 (like a throbbing engine) 5 (as if two voices, staccato notes extremely clipped) 11 mp pp 15 18 mp pp pp 21 pp mp 26 mp 27 PREVIEW Copyright © 2007 Pamela J. Marshall 28 mf 29 f 33 mf 38 p mp 43 mf 48 mp 51 pp 54 mp p 57 p mf 61 PREVIEWmp 64 p ppp 2 Spindrift Music Company Publishing contemporary classical music and promoting its performance and appreciation 38 Dexter Road Lexington MA 02420-3304 USA 781-862-0884 [email protected] www.spindrift.com Selected Music by Pamela J. -

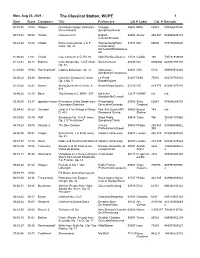

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Mon, Aug 23, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 12:02 Wagner Die Meistersinger: Selections Chicago 05288 BMG 63301 090266330126 (for orchestra) Symphony/Reiner 00:14:3208:54 Handel Concerto in D English 04894 Archiv 453 451 028945345123 Concert/Pinnock 00:24:26 34:44 Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2 in F Weissenberg/Paris 01070 EMI 69036 077776903620 minor, Op. 21 Conservatory Orchestra/Skrowaczew ski 01:00:40 11:01 Vivaldi Lute Concerto in D, RV 93 Isbin/Pacifica Quartet 13728 Cedille 190 735131919029 01:12:4125:17 Brahms Cello Sonata No. 1 in E minor, Mork/Grimaud 07246 DG 0006904 028947757191 Op. 38 01:38:5819:54 Rachmaninoff Caprice bohemien, Op. 12 Vancouver 03341 CBC 5143 059582514320 Symphony/Comissiona 02:00:2209:26 Geminiani Concerto Grosso in C minor, La Petite 01027 DHM 77010 054727701023 Op. 2 No. 5 Bande/Kuijken 02:10:4834:32 Mozart String Quintet In G minor, K. Beyer/Melos Quartet 01130 DG 419 773 028941977328 516 02:46:2012:15 Bach Trio Sonata in C, BWV 1037 Ida & Ani 12237 CMNW n/a n/a Kavafian/McDermott 03:00:0503:37 Ippolitov-Ivanov Procession of the Sardar from Philadelphia 03983 Sony 62647 074646264720 Caucasian Sketches Orchestra/Ormandy Classical 03:04:4256:53 Schubert Octet in F for Strings & Winds, Fine Arts Quartet/NY 04503 Boston 143 n/a D. 803 Woodwind Quintet Skyline 04:03:0535:15 Raff Symphony No. 10 in F minor, Basel Radio 08615 Tudor 786 761991107862 Op. 213 "In Autumn" Symphony/Travis 1 04:39:2009:45 Strauss Jr. -

Christianialiv

Christianialiv Works from Norway’s Golden Age of wind music Christianialiv The Staff Band of the Norwegian Armed Forces The second half of the 19th century is often called the “Golden Age” of Norwegian music. The reason lies partly in the international reputations established by Johan Svendsen and Edvard Grieg, but it also lies in the fact that musical life in Norway, at a time of population growth and economic expansion, enjoyed a period of huge vitality and creativity, responding to a growing demand for music in every genre. The Staff Band of the Norwegian Armed Forces (to use its modern name) played a key role in this burgeoning musical life not just by performing music for all sections of society, but also by discovering and fostering musical talent in performers and composers. Johan Svendsen, Adolf Hansen, Ole Olsen and Alfred Evensen, whose music we hear on this album, can therefore be called part of the band’s history. Siste del av 1800-tallet er ofte blitt kalt «gullalderen» i norsk musikk. Det skyldes ikke bare Svendsens og Griegs internasjonale posisjon, men også det faktum at musikklivet i takt med befolkningsøkning og økonomiske oppgangstider gikk inn i en glansperiode med et sterkt behov for musikk i alle sjangre. I denne utviklingen spilte Forsvarets stabsmusikkorps en sentral rolle, ikke bare som formidler av musikkopplevelser til alle lag av befolkningen, men også som talentskole for utøvere og komponister. Johan Svendsen, Adolf Hansen, Ole Olsen og Alfred Evensen er derfor en del av korpsets egen musikkhistorie. The Staff Band of the Norwegian Armed Forces / Ole Kristian Ruud Recorded in DXD 24bit/352.8kHz 5.1 DTS HD MA 24/192kHz 2.0 LPCM 24/192kHz + MP3 and FLAC EAN13: 7041888519027 q e 101 2L-101-SABD made in Norway 20©14 Lindberg Lyd AS 7 041888 519027 Johan Svendsen (1840-1911) Symfoni nr. -

Autumn/Winter Season 2021 Concerts at the Bridgewater Hall Music Director Sir Mark Elder Ch Cbe a Warm Welcome to the Hallé’S New Season!

≥ AUTUMN/WINTER SEASON 2021 CONCERTS AT THE BRIDGEWATER HALL MUSIC DIRECTOR SIR MARK ELDER CH CBE A WARM WELCOME TO THE HALLÉ’S NEW SEASON! We are all thrilled to be able to welcome everyone back to The Bridgewater Hall once more for a full, if shortened, Hallé autumn season. As we glimpse normality again, we can, together, look forward to some magnificent music-making. We will announce our spring concerts in October, but until then there are treasures to be discovered and wonderful stories to be told. Many of you will look forward to hearing some of the repertoire’s great masterpieces, heard perhaps afresh after so long an absence. We particularly look forward to performing these works for people new to our concerts, curious and keen to experience something special. 2 THE HALLÉ’S AUTUMN/WINTER SEASON 2021 AT THE BRIDGEWATER HALL My opening trio of programmes includes Sibelius’s ever-popular Second Symphony, Elgar’s First – given its world premiere by the Hallé in 1908 – and Brahms’s glorious Third, tranquil and poignant, then dramatic and peaceful once more. Delyana Lazarova, our already acclaimed Assistant Conductor, will perform Dvoˇrák’s ‘New World’ Symphony and Gemma New will conduct Copland’s euphoric Third, with its finale inspired by the composer’s own Fanfare for the Common Man. You can look forward to Mussorgsky’s Pictures from an Exhibition, in Ravel’s famous arrangement, Nicola Benedetti playing Wynton Marsalis’s Violin Concerto, Boris Giltburg performing Rachmaninov’s Fourth Piano Concerto, Natalya Romaniw singing Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs and Elisabeth Brauß playing Grieg’s wonderfully Romantic Piano Concerto. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

A Century of Ibsen

; A CENTURY OF IBSEN BY HENRY CHARLES SUTER OXR liundred years ago, there was born in a Norwegian town an "infant crying in the night" who grew to be a writer, but not one "with no language but a cry." For it has been well cited that Henrik Ibsen became the apostle of those who insist on self- realization and self-expression. In those days Ibsen sensed a devo- tion to formulas that fostered the use of fantastic phrases that possessed little positive potency. Crowd psychology took the place of individual thinking, and concerted action was more active than careful deliberation. Echoes multiplied by artifice were glorified as public opinion mathematical arrangements of votes contrived in consequence, a mechanical conception of society; and ultimately humanitarianism displaced humanism. Ibsen pilloried all this and made his appeal to those who were willing to pay the price of straight thinking. Ibsen owed little to life's circumstances of lowliness, since his father became insolvent ere he reached the age of eight. So his \outh was spent in studying poetry to relieve the monotony of ap- prenticeship to an apothecary. In his twenties he was aiding the management of the theater of Bergen, his home town, but the chief outcome was that comradery critics caused him to witness drama in larger cities. Before he had seen one play produced, he had written several himself, although these are not found among those preserved for us. The wretched attic in the JVild Duck was con- jured up in his memory from childhood; when nearly forty he was often unable to buy stamps to dispatch his manuscripts ; and even at successful maturity, a "poet's pension" arrived changing neerl into frugal comfort. -

Edvard Grieg Arranged by Jeff Bailey

String Orchestra TM TEPS TO UCCESSFUL ITERATURE Grade 2½ S S L SO361F • $7.00 Edvard Grieg Arranged by Jeff Bailey Gavotte (from Holberg Suite, Op. 40) Correlated with String Basics, Book 2, page 14 SAMPLE Neil A. Kjos Music Company • Publisher 2 Steps to Successful Literature presents exceptional performance literature - concert and festival pieces - for begin- ning to intermediate string orchestras. Each piece is correlated with a specific location in String Basics – Steps to Success for String Orchestra Comprehensive Method by Terry Shade, Jeremy Woolstenhulme, and Wendy Barden. Literature reinforces musical skills, concepts, and terms introduced in the method. Sometime, a few new concepts are included. They are officially e score. The Arranger Jeff Bailey is a graduate of Old Dominion University with a bachelor’s degree in music composition and University of Virginia with a master of arts in music. He has been teaching middle school string orchestra since 1999, first in Chesterfield Public Schools in Richmond, VA, and currently in Virginia Beach Public Schools. Jeff’s teaching philosophy includes the integration and education of classical music in his middle school orchestra classrooms and often arranges music to support his curriculum. His arrangements and original works have been performed with much acclaim throughout his home state. In addition, he has composed soundtrack music for instructional videos. Jeff has been a performing rock and jazz musician for over three decades, both on guitar and bass. He lives in Virginia Beach, Virginia with his wife and three children. Basics About the Composition Gavotte (from Holberg Suite Op. 40) can be described as charming, warm, lilting, graceful, and enchanting. -

Social-Ecological Resilience in the Viking-Age to Early-Medieval Faroe Islands

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 Social-Ecological Resilience in the Viking-Age to Early-Medieval Faroe Islands Seth Brewington Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/870 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SOCIAL-ECOLOGICAL RESILIENCE IN THE VIKING-AGE TO EARLY-MEDIEVAL FAROE ISLANDS by SETH D. BREWINGTON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 © 2015 SETH D. BREWINGTON All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Anthropology to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _Thomas H. McGovern__________________________________ ____________________ _____________________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _Gerald Creed_________________________________________ ____________________ _____________________________________________________ Date Executive Officer _Andrew J. Dugmore____________________________________ _Sophia Perdikaris______________________________________ _George Hambrecht_____________________________________ -

February 07, 2018

February 07, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window “Work gives you meaning and purpose and life is empty without it.” — Stephen Hawking Start Buy CD Record Program Composer Title Performers Stock Number Barcode Time online Label Sleepers, Rimsky- 00:01 Buy Now! Sadko, Op. 5 (Symphonic Poem) Mexico City Philharmonic/Batiz MHS 512145A N/A Awake! Korsakov 00:16 Buy Now! Bach Sonata No. 3 in C, BWV 1005 Manuel Barrueco EMI 56416 724355641625 00:38 Buy Now! Strauss, R. Suite ~ Der Rosenkavalier Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Sony 88725417202 887254172024 01:02 Buy Now! Puccini Chrysanthemums Quartetto di Cremona Klanglogo 1400 4037408014007 01:10 Buy Now! Wieniawski Violin Concerto No. 1 in F sharp minor, Op.14 Bisengaliev/Polish Nat'l RSO/Wit Naxos 8.553517 730099451727 01:40 Buy Now! Telemann Concerto in F for Recorder & Bassoon Berardi/Godburn/Philomel Baroque Centaur 2366 044747236629 The Chrysanthemum (An Afro-American 02:00 Buy Now! Joplin Roy Eaton Sony 62833 074646283325 Intermezzo) 02:06 Buy Now! Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37 Wass/BBC Philharmonic/Sinaisky BBC MM221 n/a 02:46 Buy Now! Mozart Fantasia in C minor, K. 475 Alfred Brendel Philips 456 727 028945672724 03:00 Buy Now! Grieg The Last Spring ~ Two Elegiac Melodies, Op. 34 Malmö Symphony/Engeset Naxos 8.508015 747313801534 03:06 Buy Now! Prokofiev Overture ~ Semyon Kotko, Op. 81 Russian National Orchestra/Pletnev DG 439 892 028943989220 Widlund/Royal Stockholm 03:11 Buy Now! Stenhammar Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat minor Chandos 9074 095115907429 Philharmonic/Rozhdestvensky 04:00 Buy Now! Haydn Notturno No. -

Current Review

Current Review Edvard Grieg: Complete Symphonic Works Vol. III aud 92.669 EAN: 4022143926692 4022143926692 Gramophone (Mike Ashman - 2013.09.01) Aadland's Cologne Radio Grieg survey continues The first two discs in this 'Complete Symphonic Works' series (10/11, 11/11) were outstanding. This third is wholly exceptional. The presence of the overture In Autumn and the Old Norwegian Romance with Variations gives the programme a Beechamesque feel. But Aadland and his astonishingly well-integrated German ensemble – by this I mean that they are guided into a natural-sounding Nordic style – need fear nothing by way of competition, not even from the RPO's dream woodwind section. Aadland's Romance – unlike Beecham's it is complete and not marginally reorchestrated – becomes a kind of Norwegian Enigma Variations avant la lettre, mixing a large degree of symphonic seriousness with wit and Griegian nostalgia. The demonstration-class recording showcases a weight and colour of orchestration that puts this Grieg score in the correct but rarely considered position of contemporary to Strauss's early orchestral masterworks. A piece that (sssh, even on the two Beecham recordings) can sound bloated and occasional claims a place here alongside, indeed anticipates, the disguised turn-of-the-century unnamed symphonies of Rachmaninov, Elgar and the like. A similar seriousness but never overblown grandeur informs In Autumn. Aadland has already shown us in this cycle that he is good at correctly scaling miniatures both in joy and in grief. He seconds those achievements here in the characterisation of the Lyric Suite and the Sigurd Jorsalfar music, while the five minutes of Klokkeklang ('Bell-ringing') become a spooky shadow of the BØyg's music in Peer Gynt (eagerly awaited in this series).