Everyday Forms of Collective Action in Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manikganj Manikganj Is a District Located in Central Bangladesh

Manikganj Manikganj is a district located in central Bangladesh. It is a part of the Dhaka division, with an area of 1,379 square kilometres. It is one of the nearest districts to Dhaka, only 70 kilometres away from the city. It bound by the Tangail district in the north, Dhaka district in the east, Faridpur district in the south, the Padma and Jamuna rivers Photo credit: BRAC and the districts of Pabna and Rajbari in the west. The main Ayesha Abed Foundation was started in 1978 as part of BRAC’s development interventions to organise, train and support rural women through traditional handicrafts rivers are the Padma, Jamuna, Dhaleshwari, Ichamati and General information Targeting the ultra poor Kaliganga. Specially targeted ultra Population 1,440,000 poor (STUP) members 450 This city is surrounded by rivers. As Unions 65 Others targeted ultra a result few of the sub-districts are Villages 1,873 poor (OTUP) members 725 affected by river bank erosion every Children (0-15) 860,000 Asset received 450 year. The people of Manikganj Training received 725 Primary schools 607 are mostly involved in agriculture. Healthcare availed 175 BRAC started its operation here Literacy rate 56% in 1974. Right now, most of Hospitals 7 Education BRAC’s core programmes, such NGOs 83 Primary schools 63 Banks 35 as microfinance, education (BEP), Pre-primary schools 225 health, nutrition and population Bazaars 98 Adolescent development (HNPP), targeting the ultra poor programme (ADP) centres 298 (TUP), community empowerment Community libraries (CEP), migration and human rights At a glance (gonokendros) 53 and legal aid services (HRLS). -

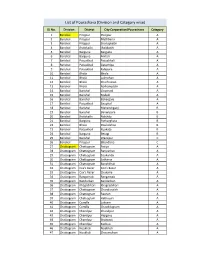

List of Pourashava (Division and Category Wise)

List of Pourashava (Division and Category wise) SL No. Division District City Corporation/Pourashava Category 1 Barishal Pirojpur Pirojpur A 2 Barishal Pirojpur Mathbaria A 3 Barishal Pirojpur Shorupkathi A 4 Barishal Jhalokathi Jhalakathi A 5 Barishal Barguna Barguna A 6 Barishal Barguna Amtali A 7 Barishal Patuakhali Patuakhali A 8 Barishal Patuakhali Galachipa A 9 Barishal Patuakhali Kalapara A 10 Barishal Bhola Bhola A 11 Barishal Bhola Lalmohan A 12 Barishal Bhola Charfession A 13 Barishal Bhola Borhanuddin A 14 Barishal Barishal Gournadi A 15 Barishal Barishal Muladi A 16 Barishal Barishal Bakerganj A 17 Barishal Patuakhali Bauphal A 18 Barishal Barishal Mehendiganj B 19 Barishal Barishal Banaripara B 20 Barishal Jhalokathi Nalchity B 21 Barishal Barguna Patharghata B 22 Barishal Bhola Doulatkhan B 23 Barishal Patuakhali Kuakata B 24 Barishal Barguna Betagi B 25 Barishal Barishal Wazirpur C 26 Barishal Pirojpur Bhandaria C 27 Chattogram Chattogram Patiya A 28 Chattogram Chattogram Bariyarhat A 29 Chattogram Chattogram Sitakunda A 30 Chattogram Chattogram Satkania A 31 Chattogram Chattogram Banshkhali A 32 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Cox’s Bazar A 33 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Chakaria A 34 Chattogram Rangamati Rangamati A 35 Chattogram Bandarban Bandarban A 36 Chattogram Khagrchhari Khagrachhari A 37 Chattogram Chattogram Chandanaish A 38 Chattogram Chattogram Raozan A 39 Chattogram Chattogram Hathazari A 40 Chattogram Cumilla Laksam A 41 Chattogram Cumilla Chauddagram A 42 Chattogram Chandpur Chandpur A 43 Chattogram Chandpur Hajiganj A -

A Case Study of Manikganj Sadar Upazila

Journal of Geographic Information System, 2015, 7, 579-587 Published Online December 2015 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jgis http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jgis.2015.76046 Dynamics of Land Use/Cover Change in Manikganj District, Bangladesh: A Case Study of Manikganj Sadar Upazila Marju Ben Sayed, Shigeko Haruyama Department of Environment Science and Technology, Mie University, Tsu, Japan Received 29 October 2015; accepted 1 December 2015; published 4 December 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract This study revealed land use/cover change of Manikganj Sadar Upazila concerning with urbaniza- tion of Dhaka city. The study area also offers better residential opportunity and food support for Dhaka city. The major focus of this study is to find out the spatial and temporal changes of land use/cover and its effects on urbanization while Dhaka city is an independent variable. For analyz- ing land use/cover change GIS and remote sensing technique were used. The maps showed that, between 1989 and 2009 built-up areas increased approximately +12%, while agricultural land decreased −7%, water bodies decreased about −2% and bare land decreased about −2%. The sig- nificant change in agriculture land use is observed in the south-eastern and north eastern site of the city because of nearest distance and better transportation facilities with Dhaka city. This study will contribute to the both the development of sustainable urban land use planning decisions and also for forecasting possible future changes in growth patterns. -

Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 10 04 10 04

Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 BARISAL DIVISION 10 04 BARGUNA 10 04 09 AMTALI 10 04 19 BAMNA 10 04 28 BARGUNA SADAR 10 04 47 BETAGI 10 04 85 PATHARGHATA 10 04 92 TALTALI 10 06 BARISAL 10 06 02 AGAILJHARA 10 06 03 BABUGANJ 10 06 07 BAKERGANJ 10 06 10 BANARI PARA 10 06 32 GAURNADI 10 06 36 HIZLA 10 06 51 BARISAL SADAR (KOTWALI) 10 06 62 MHENDIGANJ 10 06 69 MULADI 10 06 94 WAZIRPUR 10 09 BHOLA 10 09 18 BHOLA SADAR 10 09 21 BURHANUDDIN 10 09 25 CHAR FASSON 10 09 29 DAULAT KHAN 10 09 54 LALMOHAN 10 09 65 MANPURA 10 09 91 TAZUMUDDIN 10 42 JHALOKATI 10 42 40 JHALOKATI SADAR 10 42 43 KANTHALIA 10 42 73 NALCHITY 10 42 84 RAJAPUR 10 78 PATUAKHALI 10 78 38 BAUPHAL 10 78 52 DASHMINA 10 78 55 DUMKI 10 78 57 GALACHIPA 10 78 66 KALAPARA 10 78 76 MIRZAGANJ 10 78 95 PATUAKHALI SADAR 10 78 97 RANGABALI Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 79 PIROJPUR 10 79 14 BHANDARIA 10 79 47 KAWKHALI 10 79 58 MATHBARIA 10 79 76 NAZIRPUR 10 79 80 PIROJPUR SADAR 10 79 87 NESARABAD (SWARUPKATI) 10 79 90 ZIANAGAR 20 CHITTAGONG DIVISION 20 03 BANDARBAN 20 03 04 ALIKADAM 20 03 14 BANDARBAN SADAR 20 03 51 LAMA 20 03 73 NAIKHONGCHHARI 20 03 89 ROWANGCHHARI 20 03 91 RUMA 20 03 95 THANCHI 20 12 BRAHMANBARIA 20 12 02 AKHAURA 20 12 04 BANCHHARAMPUR 20 12 07 BIJOYNAGAR 20 12 13 BRAHMANBARIA SADAR 20 12 33 ASHUGANJ 20 12 63 KASBA 20 12 85 NABINAGAR 20 12 90 NASIRNAGAR 20 12 94 SARAIL 20 13 CHANDPUR 20 13 22 CHANDPUR SADAR 20 13 45 FARIDGANJ -

Top 25 Natural Disasters in Bangladesh According to Number of Killed(1901-2000)

Top 25 Natural Disasters in Bangladesh according to Number of Killed(1901-2000) DamageUS$ Rank DisNo Glide No. DisType DisName Year Month Day Killed Injured Homeless Affected TotAff ('000s) Location PrimarySource 1 19180001 EP-1918-0001-BGD Epidemic 1918 393,000 Nationwide US Gov:OFDA 2 19700063 ST-1970-0063-BGD Wind storm 1970 11 12 300,000 3,648,000 3,648,000 86,400 Khulna, Chittagong US Gov:OFDA Cox's Bazar, Chittagong, Patuakhali, Noakhali, Bhola, 3 19910120 ST-1991-0120-BGD Wind storm Brendan 1991 4 30 138,866 138,849 300,000 15,000,000 15,438,849 1,780,000 Barguna UN:OCHA 4 19420008 ST-1942-0008-BGD Wind storm 1942 10 61,000 W Sundarbans US Gov:OFDA 5 19650028 ST-1965-0028-BGD Wind storm 1965 5 11 36,000 600,000 10,000,000 10,600,000 57,700 Barisal Dist US Gov:OFDA 6 19740034 FL-1974-0034-BGD Flood 1974 7 28,700 2,000,000 36,000,000 38,000,000 579,200 Nationwide US Gov:OFDA 7 19650034 ST-1965-0034-BGD Wind storm 1965 6 12,047 Coastal area Govern:Japan 8 19630013 ST-1963-0013-BGD Wind storm 1963 5 28 11,500 1,000,000 1,000,000 46,500 Chittagong; & Noakhali US Gov:OFDA 9 19610004 ST-1961-0004-BGD Wind storm 1961 5 9 11,000 11,900 Meghna Estuary US Gov:OFDA 10 19600001 FL-1960-0001-BGD Flood 1960 10,000 Nationwide US Gov:OFDA Coastal Area From Patuakhali 11 19850063 ST-1985-0063-BGD Wind storm 1985 5 25 10,000 510,000 1,300,000 1,810,000 To Chittagong US Gov:OFDA 12 19600031 ST-1960-0031-BGD Wind storm 1960 10 30 5,149 200,000 200,000 Chittagong US Gov:OFDA 13 19410003 ST-1941-0003-BGD Wind storm 1941 5 21 5,000 Bhola/E Meghna Estuary -

Chapter 1 Introduction Summary Report CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Summary Report Chapter 1 Introduction Summary Report CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study The Peoples Republic of Bangladesh has a population of 123 million (as of June 1996) and a per capita GDP (Fiscal Year 1994/1995) of US$235.00. Of the 48 nations categorized as LLDC, Bangladesh is the most heavily populated. Even after gaining independence, the nation repeatedly suffers from floods, cyclones, etc.; 1/3 of the nation is inundated every year. Shortage in almost all sectors (e.g. development funds, infrastructure, human resources, natural resources, etc.) also leaves both urban and rural regions very underdeveloped. The supply of safe drinking water is an issue of significant importance to Bangladesh. Since its independence, the majority of the population use surface water (rivers, ponds, etc.) leading to rampancy in water-borne diseases. The combined efforts of UNICEF, WHO, donor countries and the government resulted in the construction of wells. At present, 95% of the national population depends on groundwater for their drinking water supply, consequently leading to the decline in the mortality rate caused by contagious diseases. This condition, however, was reversed in 1990 by problems concerning contamination brought about by high levels of arsenic detected in groundwater resources. Groundwater contamination by high arsenic levels was officially announced in 1993. In 1994, this was confirmed in the northwestern province of Nawabganji where arsenic poisoning was detected. In the province of Bengal, in the western region of the neighboring nation, India, groundwater contamination due to high arsenic levels has been a problem since the 1980s. -

Spectra Solar Power Project

Draft Initial Environmental Examination (Appendixes – Part 2 of 2) Project Number: 52362-001 April 2019 BAN: Spectra Solar Power Project Prepared by ERM India Private Limited for Spectra Solar Park Limited and the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ENVIRONMENTAL & SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF 35 MW SOLAR POWER PROJECT IN MANIKGANJ DISTRICT OF BANGLADESH APPENDIX H DC OFFICE CLEARANCE FOR CONVERSION FROM AGRICULTURAL LAND TO NON-AGRICULTURAL LAND www.erm.com Version: 1.0 Project No.: 0495823 Client: Spectra Solar Park Limited 28 February 2019 ENVIRONMENTAL & SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF 35 MW SOLAR POWER PROJECT IN MANIKGANJ DISTRICT OF BANGLADESH Subject: Clearance of 141.740 acre land as non-agricultural land at Boruria Mouja, Shivalaya Upozila for construction of proposed 35 MW Solar Park by Spectra Solar Power Limited. Revenue Deputy Collector, Manikganj Dt: 03/04/2016 www.erm.com Version: 1.0 Project No.: 0495823 Client: Spectra Solar Park Limited 28 February 2019 ENVIRONMENTAL & SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF 35 MW SOLAR POWER PROJECT IN -

Contamination of Drinking-Water by Arsenic in Bangladesh: a Public Health Emergency Allan H

Contamination of drinking-water by arsenic in Bangladesh: a public health emergency Allan H. Smith,1 Elena O. Lingas,2 & Mahfuzar Rahman3 The contamination of groundwater by arsenic in Bangladesh is the largest poisoning of a population in history, with millions of people exposed. This paper describes the history of the discovery of arsenic in drinking-water in Bangladesh and recommends intervention strategies. Tube-wells were installed to provide ‘‘pure water’’ to prevent morbidity and mortality from gastrointestinal disease. The water from the millions of tube-wells that were installed was not tested for arsenic contamination. Studies in other countries where the population has had long-term exposure to arsenic in groundwater indicate that 1 in 10 people who drink water containing 500 mg of arsenic per litre may ultimately die from cancers caused by arsenic, including lung, bladder and skin cancers. The rapid allocation of funding and prompt expansion of current interventions to address this contamination should be facilitated. The fundamental intervention is the identification and provision of arsenic-free drinking water. Arsenic is rapidly excreted in urine, and for early or mild cases, no specific treatment is required. Community education and participation are essential to ensure that interventions are successful; these should be coupled with follow-up monitoring to confirm that exposure has ended. Taken together with the discovery of arsenic in groundwater in other countries, the experience in Bangladesh shows that groundwater sources throughout the world that are used for drinking-water should be tested for arsenic. Keywords: Bangladesh; arsenic poisoning, prevention and control; arsenic poisoning, therapy; water pollution, chemical, prevention and control; water treatment; environmental monitoring. -

Biri Study Report 03-12-2019

Senior Secretary Internal Resources Division and Chairman National Board Revenue Ministry of Finance MESSAGE There are concerns regarding loss of employment if tax is increased on biri, However credible data on the size of employment in the biri sector, and estimation of the impact of tax increases on employment in and revenue from the biri sector has not been readily available. To address this gap in much needed evidence, the National Board of Revenue (NBR) conducted a study in 2012 on `Revenue and Employment Outcome of Biri Taxation in Bangladesh’, with support from the World Health Organization (WHO) and Department of Economics of the Dhaka University (DU). The draft report was finalized in 2013. Considering the importance of the issue, the NBR has updated the report with the most recent data, with technical assistance from American Cancer Society (ACS), BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD), DU and WHO. I am pleased to present the findings of the report within. The report it self and the recommendations made will help policy makers to tax biri based on robust evidence. This will also help the Government to deliver aspecial programme for welfare of the workers of the biri industry including support for alternative livelihoods; generate more revenue from biri sector, and save lives by reducing consumption of biri. This report is an example of high quality normative work that NBR has led. I take this opportunity to thank the experts and academicians from WHO, DU, BIGD, ACS and NBR for their collaboration and look forward to reflecting these recommendations in public policy. -

Investigation of Chemical Contamination

J. Bangladesh Agril. Univ. 13(1): 47–54, 2015 ISSN 1810-3030 Arsenic contamination in surface and groundwater in major parts of Manikganj district, Bangladesh Atia Akter, M. Y. Mia and H. M. Zakir1* Department of Environmental Science and Resource Management, Mawlana Bhashani Science and Technology University, Tangail-1902, Bangladesh and 1Department of Agricultural Chemistry, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh-2202, Bangladesh, *E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The contamination of groundwater by arsenic (As) in Bangladesh is the largest poisoning of population in history, with millions of people exposed. Thirty (30) water samples were collected from 5 different Upazilas of Manikganj district in Bangladesh to determine the concentration of As as well as to assess the level of contamination. Concentrations of As in waters were within the range of 0.27 to 1.96; 0.43 to 5.09; trace to 6.69 mg L-1 at Singair, Harirampur and Ghior Upazila, respectively. But the concentration of As in waters both of Manikganj sadar and Shivalaya Upazila were trace. All surface and groundwater samples of Singair and Harirampur, and 4 groundwater samples of Ghior Upazila’s exceeded Bangladesh standard value for As concentration (0.05 mgL-1). The highest As concentration (6.69 mgL-1) was found in groundwater of Baliakhora village of Ghior upazila in Manikganj district. The cation chemistry indicated that among 30 water samples, 15 showed dominance sequence as Mg2+ > Ca2+ > Na+ > K+ and 14 samples as Ca2+ > Mg2+ > Na+ > K+. On the other hand, the dominant anion in water samples was Cl- followed by - 2- 2- HCO3 and SO4 . -

Financing Brick Kiln Efficiency Improvement Project – Stone Bricks Limited

Environment and Social Due Diligence Report August 2014 BAN: Financing Brick Kiln Efficiency Improvement Project – Stone Bricks Limited Prepared by Bangladesh Bank for the Asian Development Bank The Environment and Social Due Diligence Report is a document owned by the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Environmental due Diligence Report of Stone Bricks Ltd. At Pukhuria, Ghior, Manikganj Project Background Due Diligence Report on Environment and Social Safeguards Stone Bricks Limited (SBL) Pukhuria , Ghior, Manikganj August 2014 Environmental Due Diligence Report Page | 1 Environmental due Diligence Report of Stone Bricks Ltd. At Pukhuria, Ghior, Manikganj Project Background Date: September 20, 2014 Project Director, Brick Sector Development Project & General Manager Green Banking and CSR Department Bangladesh Bank Motijjel, Dhaka Subject: Submission of the Environment and Social Safeguard Report Dear Sir: Pursuant to the Annexure A of the Contract for Consulting Services between the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Xian Research and Design Institute of Wall and Roof Materials ives Inc. (CEA), United States, signed on 3rd June 2013, we are submitting the following 3 (three) Environment and SocialX)AN, Safeguard Peoples’ DueRepublic Diligence Of China,Reports Joint of the ventured sub-projects with for Clean your Energy perusal Alternatand approval: Sl Name of the Sub- Areas Brick Kiln NO. -

Spectra Solar Power Project

Draft Initial Environmental Examination (Main Report – Part 1 of 4) Project Number: 52362-001 April 2019 BAN: Spectra Solar Power Project Prepared by ERM India Private Limited for Spectra Solar Park Limited and the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Document details Document title Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of 35 MW Solar Power Project, Manikganj, Bangladesh Document subtitle Draft ESIA Report Project No. 0495823 Date 12 April 2019 Version 1.0 Author Salil Das, Dwaipayan Dutta, Soumi Ghosh, Naval Chaudhary Client Name Spectra Solar Park Limited Document history ERM approval to issue Version Revision Author Reviewed by Name Date Comments www.erm.com Version: 1.0 Project No.: 0495823 Client: Spectra Solar Park Limited 12 April 2019 Signature Page 12 April 2019 Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of 35 MW Solar Power Project, Manikganj, Bangladesh Draft ESIA Report [Double click to insert signature] [Double click to insert signature] Neena Singh Naval Chaudhary Managing Partner Principal Consultant [Double click to insert signature] Soumi Ghosh Senior Consultant ERM India Private Limited Building 10A 4th Floor, DLF Cyber City Gurgaon, NCR – 122002 Tel: 91 124 417 0300 Fax: 91 124 417 0301 © Copyright 2019 by ERM Worldwide Group Ltd and / or its affiliates (“ERM”).