Making Montreal's Indoor City Accessible for People with Disabilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels in Afghanistan: an Annotated Bibliography by R

Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels in Afghanistan: An Annotated Bibliography by R. Lee Hadden Topographic Engineering Center November 2005 US Army Corps of Engineers 7701 Telegraph Road Alexandria, VA 22315-3864 Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels In Afghanistan Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE 30-11- 2. REPORT TYPE Bibliography 3. DATES COVERED 1830-2005 2005 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER “Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats and Tunnels 5b. GRANT NUMBER In Afghanistan: An Annotated Bibliography” 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER HADDEN, Robert Lee 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT US Army Corps of Engineers 7701 Telegraph Road Topographic Alexandria, VA 22315- Engineering Center 3864 9.ATTN SPONSORING CEERD / MONITORINGTO I AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

The Other White City

Arch 442 - UG4-Wallenberg Studio/Winter 2009 Studio Mankouche Alfred A. Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning University of Michigan Stanley Kubrick, 2001: A Space Odyssey, 19681 1,200 Feet Below Detroit; the Other White City Salt mining in Detroit began in 1896 with the sinking of a 1,100 foot shaft, but its investors went broke. Although there have been no deaths in the mines since, flooding and natural gas killed six men during the original construction. Today the 1,500 acre mine expels 10 ton loads of salt every few seconds. Salt is an ingredient essential to our survival. Empires have risen and fallen around their access to salt. Salt a critical chemical compound in numerous manufacturing processes was critical to the development of Detroit as a major industrial city. As such the excavation of the underground salt city has a spatial relation with the development of the above ground city. This studio would like to honor the legacy of Raoul Wallenberg, by addressing issues of social justice centered around the theme of two cities, an underground crystallized city of labor and an above ground city of lost and replaced labor. With the increasing sophistication of digital mechanization mining has become an incrementally safer practice. The greater safety and efficiency has the downside of reducing the need for human labor. While we are saving lives paradoxically we are at the same time ruining livelihoods. What will or can become of this underground city? Will it be like Carlsbad, New Mexico a safe place to store refuse? Could it be like the catacombs of Rome, a place to bury the dead? Could it be a fall out shelter a la Doctor Strange Love? A place to archive information such as the Corbis Iron Mountain facility in Pennsylvania? How does any of this relate to what is going on above ground? Tectonically this studio will be concerned entirely with interior space. -

AECOM Top Projects 2017

AECOM Top Projects 2017 #13 Turcot Interchange #6 Romaine Complex #59 Region of Waterloo ION LRT #53 Giant Mine Remediation #65 Lions Gate Secondary Wastewater Treatment Plant #82 Wilson Facility Enhancement and Yard Expansion AECOM Top Projects 2017 With $186.4 billion invested in Canada’s Top100 Projects of 2017, the country is experiencing record investment in creating AECOM Top Projects 2017 and improving public sector infrastructure from coast-to-coast. Those investments are creating tens of thousands of jobs and providing a foundation for the country’s growing economy. EDITOR In 2017, AECOM again showed why it is a leader in Canada’s Andrew Macklin infrastructure industry. In this year’s edition of the ReNew Canada Top100 projects report, AECOM was involved in PUBLISHER 29 of the 100 largest public sector infrastructure projects, Todd Latham one of just a handful of businesses to reach our Platinum Elite status. Those 29 projects represented just under $61.5 billion, close to one-third of the $186.4 billion list. ART DIRECTOR & DESIGN Donna Endacott AECOM’s involvement on the Top100 stretches across multiple sectors, working on big infrastructure projects in the transit, ASSOCIATE EDITOR energy, transportation, health care and water/wastewater Katherine Balpatasky sectors. That speaks to the strength of the team that the company has built in Canada to deliver transformational assets across a multitude of industries. Through these projects, AECOM has also shown its leadership in both putting together teams, and working as a member of a team, to help produce the best project possible for the client. As a company that prides itself on its ability “to develop and implement innovative solutions to the world’s most complex challenges,” they have shown they are willing to work with AECOM is built to deliver a better all involved stakeholders to create the greatest possible world. -

M a C a S 2 0

M A C A S 2 0 1 9 Mathematics and its connections to the arts and sciences Program Faculty of Education McGill University Montreal, Quebec, Canada June 18 – 21, 2019 Table of Content Welcome to the 2019 MACAS Symposium .................................................................................... 3 International Program Committee (IPC) .................................................................................... 3 Local Organizing Committee (LOC) ............................................................................................ 4 Message from the International Program Committee (IPC) ...................................................... 5 Message from the Local Organizing committee (LOC) ............................................................... 6 Getting to the Venue ...................................................................................................................... 7 Getting to the Venue from the Airport ...................................................................................... 7 Getting to the Venue by Car ....................................................................................................... 8 Parking at the Venue .................................................................................................................. 9 Transit in Montreal: Metro ........................................................................................................ 9 Regarding the MACAS Symposium .............................................................................................. -

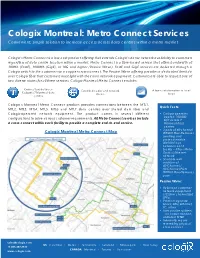

Cologix Montreal: Metro Connect Services Convenient, Simple Solution to Increase Access Across Data Centres Within a Metro Market

Cologix Montreal: Metro Connect Services Convenient, simple solution to increase access across data centres within a metro market Cologix’s Metro Connect is a low-cost product offering that extends Cologix’s dense network availability to customers regardless of data centre location within a market. Metro Connect is a fibre-based service that offers bandwidth of 100Mb (FastE), 1000Mb (GigE), or 10G and higher (Passive Wave). FastE and GigE services are delivered through a Cologix switch to the customer via a copper cross-connect. The Passive Wave offering provides a dedicated lambda over Cologix fibre that customers must light with their own network equipment. Customers are able to request one of two diverse routes for all three services. Cologix Montreal Metro Connect enables: Connections between Extended carrier and network A low-cost alternative to local Cologix’s 7 Montreal data choice loops centres Cologix’s Montreal Metro Connect product provides connections between the MTL1, Quick Facts: MTL2, MTL3, MTL4, MTL5, MTL6 and MTL7 data centres over shared dark fibre and Cologix-operated network equipment. The product comes in several different • Cologix operates confgurations to solve various customer requirements. All Metro Connect services include approx. 100,000 SQF across 7 a cross-connect within each facility to provide a complete end-to-end service. Montreal data centres • 2 pairs of 40-channel Cologix Montreal Metro Connect Map DWDM Mux-Demuxes (working and protect) enable 40x100 Gbps between each facility = 4Tbps Metro Optical -

An Innovative Model, an Integrated Network

RÉSEAU ÉLECTRIQUE MÉTROPOLITAIN An innovative model, an integrated network / Presentation of the #ProjetREM cdpqinfra.com THE REM: A PROJECT WITH IMPACT The REM is a fully automated, electric light rail transit (LRT) system, made up of 67 km of dedicated rail lines, with 50% of the tracks occupying existing rail corridors and 30% following existing highways. The REM will include four branches connecting downtown Montréal, the South Shore, the West Island, the North Shore and the airport, resulting in two new high-frequency public transit service lines to key employment hubs. A team of close to 400 experts is contributing to this project, ensuring well-planned, efficient and effective integration with the other transit networks. All sorts of elements are being considered, including the REM’s integration into the urban fabric and landscape, access to stations and impacts on the environment. Based on the current planning stage, the REM would become the fourth largest automated transit network in the world, with 27 stations, 13 parking facilities and 9 bus terminals, in addition to offering: • frequent service (every 3 to 12 minutes at peak times, depending on the stations), 20 hours a day (from 5:00 a.m. to 1:00 a.m.), 7 days a week; • reliable and punctual service, through the use of entirely dedicated tracks; • reduced travel time through high carrying capacity and rapid service; • attention to user safety and security through cutting-edge monitoring; • highly accessible stations (by foot, bike, public transit or car) and equipped with elevators and escalators to improve ease of travel for everyone; • flexibility to espondr to increases in ridership, with the possibility of having trains pass through stations every 90 seconds. -

Cappadocia Underground City Underground Cappadocia the Unsolvable Secret of of Secret Unsolvable the Cappadocia Underground Cities

Özkonak Zelve, the Miracle of Underground Nature City Don’t miss Özkonak Underground City Visiting Hours April 1 - October 31 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 8.00 8.00 8.00 8.00 8.00 8.00 8.00 19.00 19.00 19.00 19.00 19.00 19.00 19.00 Box Office Closing: 18.15 October 31- April 1 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 8.00 8.00 8.00 8.00 8.00 8.00 8.00 17.00 17.00 17.00 17.00 17.00 17.00 17.00 Box Office Closing: 16.15 TurkishMuseums officialturkishmuseums TurkishMuseums TurkishMuseums TurkishMuseums Address Özkonak Yeraltı Şehri Yolu, 50500 Avanos/NEVŞEHİR | Phone: +90384 218 25 00 Please visit the website for current information. www.muze.gov.tr Cappadocia Underground City Underground Cappadocia The Unsolvable Secret of of Secret Unsolvable The Cappadocia Underground Cities There are about 150-200 of underground settlements of various sizes, which are one of the most interesting cultural riches of the Cappadocia Region. This number may increase even more since there are large and small rock settlements in all the towns and villages in the Cappadocia Region. Most of these rock settlements were built by carving down soft tuff downwards deeply. The reason for the construction of underground cities is for people to secure themselves. Hundreds of rooms in underground cities are connected to each other through long galleries and tunnels like labyrinths. The reason why galleries are low, narrow and long is to limit the movement of the enemy. -

Underground Jerusalem: the Excavation Of

Underground Jerusalem The excavation of tunnels, channels, and underground spaces in the Historic Basin 2015 >> Introduction >> Underground excavation in Jerusalem: From the middle of the 19th century to the Six Day War >> Tunnel excavations following the Six Day War >> Tunnel excavations under archaeological auspices >> Ancient underground complexes >> Underground tunnels >> Tunnel excavations as narrative >> Summary and conclusions >> Maps >> Endnotes Emek Shaveh (cc) | Email: [email protected] | website www.alt-arch.org Emek Shaveh is an organization of archaeologists and heritage professionals focusing on the role of tangible cultural heritage in Israeli society and in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We view archaeology as a resource for strengthening understanding between different peoples and cultures. September 2015 Introduction Underground excavation in Jerusalem: From the middle of the The majority of the area of the Old City is densely built. As a result, there are very few nineteenth century until the Six Day War open spaces in which archaeological excavations can be undertaken. From a professional The intensive interest in channels, underground passages, and tunnels, ancient and modern, standpoint, this situation obligates the responsible authorities to restrict the number of goes back one 150 years. At that time the first European archaeologists in Jerusalem, aided excavations and to focus their attention on preserving and reinforcing existing structures. by local workers, dug deep into the heart of the Holy City in order to understand its ancient However, the political interests that aspire to establish an Israeli presence throughout the topography and the nature of the structures closest to the Temple Mount. Old City, including underneath the Muslim Quarter and in the nearby Palestinian village The British scholar Charles Warren was the first and most important of those who excavated of Silwan, have fostered the decision that intensive underground excavations must be underground Jerusalem. -

THE UNDERGROUND HIGHWAY Bart Savenije

THE UNDERGROUND HIGHWAY Bart Savenije Book Two of the Lost Books Of Talislanta The Talislanta game and fantasy world are the creations of Stephan Michael Sechi. Talislanta is a trademark of SMS, and is used here with permission. Writing: Bart Savenije. Editing, Layout, & Cartography: Paul Cunningham. First Printing, October 2010. This book may be reprinted for personal use only. For more information about the world of Talislanta, visit talislanta.com. Table of Contents Chapter 1: Travelling Underground _______________________________________ 2-5 Map: Subterranean Talislanta ___________________________________________________ 2-6 HISTORY _______________________________________________________________ 2-8 The Forgotten Age_______________________________________________________________ 2-8 The Archaen Age________________________________________________________________ 2-9 The Great Disaster______________________________________________________________ 2-10 The Phaedran Age ______________________________________________________________ 2-10 TRAVELLING UNDERGROUND____________________________________________ 2-10 The Underground Highway_______________________________________________________ 2-10 Learning the Rocks _____________________________________________________________ 2-11 Chapter 2: Excerpts from the Geological Repository in Durne________________ 2-13 THE GNOMEKIN PROTECTORATE ____________________________________________ 2-14 The Seventh Road ______________________________________________________________ 2-14 Sidebar: Station Seven -

Metropolises Study Montreal

Metropolises A metropolis is a major urban centre where power and services are concentrated, and where issues abound. People in the surrounding region and even in the national territory as a whole are drawn to it. Today metropolises are increasingly powerful, which has repercussions for the entire planet. Québec Education Program, Secondary School Education, Cycle One, p. 276 Study Territory: Montréal Note: This is an archived study file and is no longer updated. Portrait of the territory A French-speaking metropolis in North America About half of the population of the province of Québec is concentrated in the urban agglomeration of Montréal (also known as the Greater Montréal area), Québec’s largest metropolis, which has a population of 3.6. million people. The new demerged city of Montréal accounts for 1.6 million of these people, almost the entire population of the Island of Montréal. Montréal is the second largest metropolis in Canada, after Toronto, which has a metropolitan area with a population of over 5 million. In Canada, only Vancouver, Ottawa-Gatineau, Calgary and Edmonton also have metropolitan areas of over 1 million people. Updated source: Stats Canada Population profile The suburbs farthest from the centre of Montréal are experiencing the fastest population growth. In fact, for the last 10 years, the population of the city of Montréal itself has only increased slightly, with immigration compensating for the low birth rate of 1.1 children per family. Montréal is consequently a very multicultural city, with immigrants making up 28% of its population. (This percentage drops to 18% for the entire urban agglomeration). -

But Why: a Podcast for Curious Kids Are There Underground Cities

But Why: A Podcast for Curious Kids Are There Underground Cities? January 5, 2018 [00:00:20] This is [00:00:21] But Why: A Podcast For Curious Kids from Vermont Public Radio. On this show we take your questions on anything from science to art to history to ethics. And we find interesting people to help answer them. [00:00:37] Sometimes we answer them ourselves and sometimes we get to go on field trips to answer your questions. That's my favorite. I'll tell you how to ask your own question at the end of the episode. I am actually outside right now and I am not going to stay outside for very long. I am in Montreal, in Canada, and it is minus 5 degrees out. That's Fahrenheit. If you live here in Canada you'd say it's minus 20 Celsius. I am freezing. My toes are froze. This is the kind of weather that freezes the little hairs inside your nostrils. So I'm going to go inside but that's perfect because that's where we need to go [00:01:22] to answer today's question. My name is Wyatt and I live Los Angeles. And I am five years old. [00:01:32] I want to know if there is underground cities? Well it just so happens I am standing outside a sign that says "Reseau" which in Montreal represents the underground city. Let's go in. [00:01:49] Okay. I am now inside the McGill metro station. But this is more than a subway or a tube stop. -

Paris Catacombs

The Dark Underworld of the Paris Catacombs Underneath the City Hidden beneath the vibrant European city of Paris is an eerie network of old caves and tunnels housing the remains of 6 million people: The Catacombes de Paris. The Paris catacombs date as far back as the 12th century. The tunnels run like arteries, located beneath the city. They stretch as far as 200 miles at a depth of 20 metres (65 feet), equivalent to the size of a five story building. Only a small section of it is open to the public today. The majority of the network has been of-limits since 1955. But even in the area still accessible to tourists there are fascinating remnants of Paris' history. The catacombs have existed since the 12th century, when the mining of limestone quarries to provide bricks for the city's buildings created as a side efect an entire underground city. The tunnels lie mostly under the southern part of the metropolis. It was only during the second half of the 18th century, that the former limestone mines were transformed into burial places. The oldest and most extensive network of tunnels is under the 14th and 15th Arrondissments (districts). After a few buildings collapsed into the forgotten underground cavities in the 18th century, the city began to map The Catacomb Beginnings As Paris grew into its role as a major European hub, it eventually ran into a major problem. By the 17th century, enough people had lived and died in Paris that its cemeteries were overflowing. They were overstufed with graves to the point where corpses, at times, became uncovered.