A Tale of Two Tunnels: Exploring the Design and Cultural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Living History of Montreal's Early Jewish Community

A NEW LIFE FOR CANADIANA VILLAGE? $5 Quebec HeritageVOL 3, NO. 12 NOV-DEC. 2006 News The Bagg Shul A living history of Montreal’s early Jewish community The Street that Roared Why the fight to save Montreal milestone matters to Mile Enders Christbaum comes to Canada Decorated tree topped pudding at Sorel party Quebec CONTENT HeritageNews EDITOR President’s Message 3 CHARLES BURY School Spirit Rod MacLeod DESIGN DAN PINESE Letters 5 Opinion 6 PUBLISHER Wisdom of the rubber stamps Jim Wilson THE QUEBEC ANGLOPHONE HERITAGE NETWORK TimeLines 7 400-257 QUEEN STREET SHERBROOKE (LENNOXVILLE) One stop culture shop QUEBEC Taste of the world J1M 1K7 The unknown settlers PHONE A philanthropist’s legacy 1-877-964-0409 New owner, same purpose for Saguenay church (819) 564-9595 Canadiana Village changes hands FAX Tombstone rising 564-6872 C ORRESPONDENCE The Street that Roared 14 [email protected] Why the fight for Montreal milestone matters Carolyn Shaffer WEBSITE The Bagg Shul 17 WWW.QAHN.ORG Montreal’s early Jewish community Carolyn Shaffer Christbaum Comes to Canada 19 PRESIDENT Decorated tree topped pudding at Sorel party RODERICK MACLEOD Bridge to Suburbia 21 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Vanished English towns and the South Shore’s past Kevin Erskine-Henry DWANE WILKIN What’s in a Name? 22 HERITAGE PORTAL COORDINATOR Land of shrugs and strangers Joseph Graham MATHEW FARFAN OFFICE MANAGER Book Reviews 24 KATHY TEASDALE Adventism in Quebec The Eastern Townships Quebec Heritage Magazine is Cyclone Days produced on a bi-monthly basis by the Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network (QAHN) with the support of The HindSight 26 Department of Canadian Heritage and Quebec’s Ministere de la Culture et des Luck of the potted frog Joseph Graham Communications. -

Montreal, Québec

st BOOK BY BOOK BY DECEMBER 31 DECEMBER 31st AND SAVE $200 PER COUPLE AND SAVE $200 PER COUPLE RESERVATION FORM: (Please Print) TOUR CODE: 18NAL0629/UArizona Enclosed is my deposit for $ ______________ ($500 per person) to hold __________ place(s) on the Montreal Jazz Fest Excursion departing on June 29, 2018. Cost is $2,595 per person, based on double occupancy. (Currently, subject to change) Final payment due date is March 26, 2018. All final payments are required to be made by check or money order only. I would like to charge my deposit to my credit card: oMasterCard oVisa oDiscover oAmerican Express Name on Card _____________________________________________________________________________ Card Number ______________________________________________ EXP_______________CVN_________ NAME (as it appears on passport): o Mr. o Mrs. o Ms.______________________________________ Date of Birth (M/D/Y) _______/_______/________ NAME (as it appears on passport): o Mr. o Mrs. o Ms.______________________________________ Date of Birth (M/D/Y) _______/_______/________ NAME FOR NAME BADGE IF DIFFERENT FROM ABOVE: 1)____________________________________ 2)_____________________________________ STREET ADDRESS: ____________________________________________________________________ CITY:_______________________________________STATE:_____________ZIP:___________________ PHONE NUMBERS: HOME: ( )______________________ OFFICE: ( )_____________________ 1111 N. Cherry Avenue AZ 85721 Tucson, PHOTO CREDITS: Classic Escapes; © Festival International de Jazz de Montréal; -

Calendar of Events from Saturday, September 24, 2016 to Saturday, October 1, 2016

Calendar of events from Saturday, September 24, 2016 to Saturday, October 1, 2016 The 350th Anniversary of the Arrival of the Carignan-Salières Regiment www.chateauramezay.qc.ca November 19, 2014 to October 16, 2016 0XVHXPVDQG$WWUDFWLRQV+LVWRU\ Château Ramezay – Historic Site and Museum of Montréal | 280 Notre-Dame Street East | Metro: Champ-de-Mars Produced in collaboration with historian and archivist Michel Langlois, the exhibition traces the lives of officers and soldiers from the Carignan- Salières regiment and De Tracy's troops as they set out to carve a nation. Follow them on this great human adventure that marked not only Québec’s place names but also its patronyms and its people. Why did they come? What did they achieve? How were they equipped to face the Iroquois, not to mention Québec’s winters? Learn the answers to these questions and find out whether you are a descendant of one of these soldiers, by consulting our genealogical database. Le livre sens dessus dessous www.banq.qc.ca/activites/index.html?language_id=1 March 31, 2015 to January 8, 2017 0XVHXPVDQG$WWUDFWLRQV$UWV Grande Bibliothèque – Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec | 475 de Maisonneuve Blvd. East | Metro: Berri-UQAM )UHH$FWLYLW\ Tuesday to Thursday, 10 a.m. to 8 p.m.; Friday to Sunday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. At Their Risk and Peril | Travelling the Continent in Days of Old www.marguerite-bourgeoys.com May 15, 2015 to December 4, 2016 WR Marguerite-Bourgeoys Museum | 400 Saint-Paul Street East | Metro: Champ-de-Mars 0XVHXPVDQG$WWUDFWLRQV+LVWRU\ Pièces de collections www.banq.qc.ca/activites/itemdetail.html?language_id=1&calItemId=89958 September 15, 2015 to September 17, 2018 0XVHXPVDQG$WWUDFWLRQV+LVWRU\ Grande Bibliothèque – Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec | 475 de Maisonneuve Blvd. -

AECOM Top Projects 2017

AECOM Top Projects 2017 #13 Turcot Interchange #6 Romaine Complex #59 Region of Waterloo ION LRT #53 Giant Mine Remediation #65 Lions Gate Secondary Wastewater Treatment Plant #82 Wilson Facility Enhancement and Yard Expansion AECOM Top Projects 2017 With $186.4 billion invested in Canada’s Top100 Projects of 2017, the country is experiencing record investment in creating AECOM Top Projects 2017 and improving public sector infrastructure from coast-to-coast. Those investments are creating tens of thousands of jobs and providing a foundation for the country’s growing economy. EDITOR In 2017, AECOM again showed why it is a leader in Canada’s Andrew Macklin infrastructure industry. In this year’s edition of the ReNew Canada Top100 projects report, AECOM was involved in PUBLISHER 29 of the 100 largest public sector infrastructure projects, Todd Latham one of just a handful of businesses to reach our Platinum Elite status. Those 29 projects represented just under $61.5 billion, close to one-third of the $186.4 billion list. ART DIRECTOR & DESIGN Donna Endacott AECOM’s involvement on the Top100 stretches across multiple sectors, working on big infrastructure projects in the transit, ASSOCIATE EDITOR energy, transportation, health care and water/wastewater Katherine Balpatasky sectors. That speaks to the strength of the team that the company has built in Canada to deliver transformational assets across a multitude of industries. Through these projects, AECOM has also shown its leadership in both putting together teams, and working as a member of a team, to help produce the best project possible for the client. As a company that prides itself on its ability “to develop and implement innovative solutions to the world’s most complex challenges,” they have shown they are willing to work with AECOM is built to deliver a better all involved stakeholders to create the greatest possible world. -

Park-Extension Among the Lowest Crime Areas

FREE Bonne fête TUITION des pères ! Happy Father’s Day ! DIGITAL GRAPHIC TECHNOLOGY CALL FOR INFO ON NEXT SESSION Programs leading to a Ministry • 1 year program Of Education Diploma • State of the art 4 colour press LOANS & BURSARIES AVAILABLE • Silk screening, CNC Technical Skills • Learn the latest software, including: Photoshop, Illustrator, Quark & InDesign MARY DEROS 514 872-3103 | [email protected] Le seul journal de Parc-Extension depuis 1993 3737 Beaubien East, Montreal, Qc, H1X 1H2 Maire suppléante de Villeray-Saint-Michel-Parc-Extension Tel.: 514 376-4725 Conseillère du District de Parc-Extension The only paper in Park-Extension since 1993 www.rosemount-technology.qc.ca Vol. 27 - No. 12 14 juin / June 14, 2019 514-272-0254 www.px-news.com [email protected] 2018 Police Stats: Park-Extension among the lowest crime areas Page 7 OPEN EVERYDAY 7 AM TO 5 AM • FRIDAY AND SATURDAY 24 HOURS SENIORS SPECIAL SUPER SPECIALS SUNDAY IS FAMILY DAY Buy 2 Large Pizzas Buy 2 X-Large Pizzas and receive or 2 Jumbos Pizza 1 Medium Fries and receive FREE! 1 Family Fries FREE! EVERY 1ST MONDAY OF THE MONTH 15% OFF ONE FREE KIDS MENU MEAL *DINER ROOM ONLY PER PURCHASE OF ADULT MEAL FREE DELIVERY (minimum 12$ before tx.) 901 rue Jean Talon O. Montréal • 514 274-4147 • 514 274-8510 • missjeantalon.com Visit mobifone.ca to see all current offers MONTREAL Complexe Desjardins 175, René-Lévesque Blvd. West Place-des-Arts Metro 514 669-1880 Place du Quartier SUNNY WITH A (Chinatown) 1111, St-Urbain St Place-des-Arts Metro 514 667-0077 100% CHANCE Place Alexis Nihon 1500, Atwater Av. -

Summary of the 2018 – 2022 Corporate Plan and 2018 Operating and Capital Budgets

p SUMMARY OF THE 2018 – 2022 CORPORATE PLAN AND 2018 OPERATING AND CAPITAL BUDGETS SUMMARY OF THE 2018-2022 CORPORATE PLAN / 1 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. 5 MANDATE ...................................................................................................................................... 14 CORPORATE MISSION, OBJECTIVES, PROFILE AND GOVERNANCE ................................................... 14 2.1 Corporate Objectives and Profile ............................................................................................ 14 2.2 Governance and Accountability .............................................................................................. 14 2.2.1 Board of Directors .......................................................................................................... 14 2.2.2 Travel Policy Guidelines and Reporting ........................................................................... 17 2.2.3 Audit Regime .................................................................................................................. 17 2.2.4 Office of the Auditor General: Special Examination Results ............................................. 17 2.2.5 Canada Transportation Act Review ................................................................................. 18 2.3 Overview of VIA Rail’s Business ............................................................................................. -

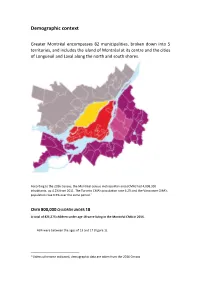

Demographic Context

Demographic context Greater Montréal encompasses 82 municipalities, broken down into 5 territories, and includes the island of Montréal at its centre and the cities of Longueuil and Laval along the north and south shores. According to the 2016 Census, the Montréal census metropolitan area (CMA) had 4,098,930 inhabitants, up 4.2% from 2011. The Toronto CMA’s population rose 6.2% and the Vancouver CMA’s population rose 6.5% over the same period.1 OVER 800,000 CHILDREN UNDER 18 A total of 821,275 children under age 18 were living in the Montréal CMA in 2016. — 46% were between the ages of 13 and 17 (Figure 1). 1 Unless otherwise indicated, demographic data are taken from the 2016 Census. Figure 1.8 Breakdown of the population under the age of 18 (by age) and in three age categories (%), Montréal census metropolitan area, 2016 Source: Statistics Canada (2017). 2016 Census, product no. 98-400-X2016001 in the Statistics Canada catalogue. The demographic weight of children under age 18 in Montréal is higher than in the rest of Quebec, in Vancouver and in Halifax, but is lower than in Calgary and Edmonton. While the number of children under 18 increased from 2001 to 2016, this group’s demographic weight relative to the overall population gradually decreased: from 21.6% in 2001, to 20.9% in 2006, to 20.3% in 2011, and then to 20% in 2016 (Figures 2 and 3). Figure 2 Demographic weight (%) of children under 18 within the overall population, by census metropolitan area, Canada, 2011 and 2016 22,2 22,0 21,8 21,4 21,1 20,8 20,7 20,4 20,3 20,2 20,2 25,0 20,0 19,0 18,7 18,1 18,0 20,0 15,0 10,0 5,0 0,0 2011 2016 Source: Statistics Canada (2017). -

Réseau Électrique Métropolitain (REM) | REM Forecasting Report

Réseau Électrique Métropolitain (REM) | REM Forecasting Report Réseau Électrique CDPQ Infra Inc. Métropolitain (REM) REM Forecasting Report Our reference: 22951103 February 2017 Client reference: BC-A06438 Réseau Électrique Métropolitain (REM) | REM Forecasting Report Réseau Électrique CDPQ Infra Inc. Métropolitain (REM) REM Forecasting Report Our reference: 22951103 February 2017 Client reference: BC-A06438 Prepared by: Prepared for: Steer Davies Gleave CDPQ Infra Inc. Suite 970 - 355 Burrard Street 1000 Place Jean-Paul-Riopelle Vancouver, BC V6C 2G8 Montréal, QC H2Z 2B3 Canada Canada +1 (604) 629 2610 na.steerdaviesgleave.com Steer Davies Gleave has prepared this material for CDPQ Infra Inc.. This material may only be used within the context and scope for which Steer Davies Gleave has prepared it and may not be relied upon in part or whole by any third party or be used for any other purpose. Any person choosing to use any part of this material without the express and written permission of Steer Davies Gleave shall be deemed to confirm their agreement to indemnify Steer Davies Gleave for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. Steer Davies Gleave has prepared this material using professional practices and procedures using information available to it at the time and as such any new information could alter the validity of the results and conclusions made. Réseau Électrique Métropolitain (REM) | REM Forecasting Report Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ -

712 & 708 Main Street, Houston

712 & 708 MAIN STREET, HOUSTON 712 & 708 MAIN STREET, HOUSTON KEEP UP WITH THE JONES Introducing The Jones on Main, a storied Houston workspace that marries classic glamour with state-of-the-art style. This dapper icon sets the bar high, with historic character – like classic frescoes and intricate masonry – elevated by contemporary co-working space, hospitality-inspired lounges and a restaurant-lined lobby. Highly accessible and high-energy, The Jones on Main is a stylishly appointed go-getter with charisma that always shines through. This is the place in Houston to meet, mingle, and make modern history – everyone wants to keep up with The Jones. Opposite Image : The Jones on Main, Evening View 3 A Historically Hip Houston Landmark A MODERN MASTERPIECE THE JONES circa 1945 WITH A TIMELESS PERSPECTIVE The Jones on Main’s origins date back to 1927, when 712 Main Street was commissioned by legendary Jesse H. Jones – Houston’s business and philanthropic icon – as the Gulf Oil headquarters. The 37-story masterpiece is widely acclaimed, a City of Houston Landmark recognized on the National Register of Historic Places. Together with 708 Main Street – acquired by Jones in 1908 – the property comprises an entire city block in Downtown Houston. Distinct and vibrant, The Jones touts a rich history, Art Deco architecture, and famous frescoes – soon to be complemented by a suite of one-of-a-kind, hospitality- inspired amenity spaces. Designed for collaboration and social interaction, these historically hip spaces connect to a range of curated first floor retail offerings, replete with brand new storefronts and activated streetscapes. -

An Innovative Model, an Integrated Network

RÉSEAU ÉLECTRIQUE MÉTROPOLITAIN An innovative model, an integrated network / Presentation of the #ProjetREM cdpqinfra.com THE REM: A PROJECT WITH IMPACT The REM is a fully automated, electric light rail transit (LRT) system, made up of 67 km of dedicated rail lines, with 50% of the tracks occupying existing rail corridors and 30% following existing highways. The REM will include four branches connecting downtown Montréal, the South Shore, the West Island, the North Shore and the airport, resulting in two new high-frequency public transit service lines to key employment hubs. A team of close to 400 experts is contributing to this project, ensuring well-planned, efficient and effective integration with the other transit networks. All sorts of elements are being considered, including the REM’s integration into the urban fabric and landscape, access to stations and impacts on the environment. Based on the current planning stage, the REM would become the fourth largest automated transit network in the world, with 27 stations, 13 parking facilities and 9 bus terminals, in addition to offering: • frequent service (every 3 to 12 minutes at peak times, depending on the stations), 20 hours a day (from 5:00 a.m. to 1:00 a.m.), 7 days a week; • reliable and punctual service, through the use of entirely dedicated tracks; • reduced travel time through high carrying capacity and rapid service; • attention to user safety and security through cutting-edge monitoring; • highly accessible stations (by foot, bike, public transit or car) and equipped with elevators and escalators to improve ease of travel for everyone; • flexibility to espondr to increases in ridership, with the possibility of having trains pass through stations every 90 seconds. -

DOWNTOWN the OAKS Hobby Airport 24 M I N

THE WOODLANDS KINGWOOD TOMBALL SPRING ATSCOCITA 290 HUMBLE LOCATION WILLOWBROOK 59 CYPRESS 90 6 The Heights 15 min. IAH 99 River Oaks 17 min. 45 West University Place 14 min. Memorial 23 min. 290 59 90 The Galleria 16 min. THE Tanglewood 17 min. HEIGHTS 10 KATY MEMORIAL 10 The Medical Center 19 min. 610 TANGLEWOOD RIVER DOWNTOWN THE OAKS Hobby Airport 24 m i n . GALLERIA WEST George Bush Intercontinental UNIVERSITY 27 m i n. THE Airport (IAH) PLACE MEDICAL PORT OF CENTER HOUSTON 610 Sugar Land 27 m i n. 59 Port of Houston 40 min. Trinity Bay 99 Baybrook 32 min. HOBBY AIRPORT 90 Katy 37 min. 45 Cypress 35 min. Galveston Bay 288 SUGAR LAND BAYBROOK The Woodlands 36 min. 59 6 PEARLAND Kingwood 38 min. 65,720 150,000 22 residents currently live employees work Hotels downtown downtown (2 mile radius) 11 2,936 220,000 million people attend downtown Houston new residential units people visit downtown culture and entertainment planned or under on a daily basis attractions annually construction 1.2 million 7, 300 1,500 43.7 million 1.5 million people stay in downtown hotel rooms new hotel rooms SF of existing SF of office under Houston hotels annually under construction office space construction MAJOR EMPLOYERS Franklin Franklin Lofts? Old Cotton Islamic Hermann The Corinthian Harris Exchange Dawah Center Harris Lofts County County Family Law Harris Garage Center County Foley Sally’s Hotel Icon Congress Plaza Civil Courthouse George Bush Building (Jury Assembly) House Monument Congress Market Market 1414 Square Congress Garage Square Houston Hamilton Street Sesquicentennial Harris County Ballet Park Residences Majestic 1910 Courthouse Harris County Park Metro Harris County Juvenile Justice Admin. -

Liste Des Immeubles Nom De L'immeuble / Building's Name Adresse / Address Ville / City Code Postal / Postal Code 1001, Rue Sherb

Liste des immeubles Nom de l'immeuble / Building's name Adresse / Address Ville / City Code postal / Postal Code 1001, rue Sherbrooke 1001, rue Sherbrooke Montréal h2l 1l3 1100, boulevard René-Lévesque 1100, boulevard René-Lévesque Ouest Montréal H3B 4N4 1250, boulevard René-Lévesque 1250, boulevard René-Lévesque Ouest, 27e étage Montréal H3B 4W8 150 des commandeurs 150 des commandeurs Lévis g6v8m6 2001 Robert-Bourassa 2001 Robert-Bourassa Montreal H3A 2A6 204, boul. de Montarville 204, boul. de Montarville Boucherville J4B 6S2 600 de Maisonneuve Ltée (Tour KPMG) 600, boul. de Maisonneuve Ouest, bureau 510 Montréal H3A 3J2 7001, boul. St-Laurent 7001, boul. St-Laurent Montréal H2S 3E3 85, St-Charles Ouest 85, St-Charles Ouest Longueuil J4H 1C5 ALLIED - 111 boulevard Robert-Bourassa 75 rue Queen, Bureau 3100 Montreal H3C 2N6 ALLIED – 50 Queen 75 rue Queen, Bureau 3100 Montreal H3C 2N6 ALLIED - 5445 avenue de Gaspé 5445 avenue de Gaspé, Bureau 250 Montreal H2T 3B2 ALLIED - 5455 avenue de Gaspé 5445 avenue de Gaspé, Bureau 250 Montreal H2T 3B2 ALLIED - 5505 ST-LAURENT 75 rue Queen, Bureau 3100 Montreal H3C 2N6 ALLIED - 6300 Avenue du Parc 6300 Avenue du Parc Montreal H2V 4S6 ALLIED – 700 Wellington & 75 Queen 75 rue Queen, Bureau 3100 Montreal H3C 2N6 ALLIED – 80 Queen & 87 Prince 75 rue Queen, Bureau 3100 Montreal H3C 2N6 Carrefour du Nord-Ouest 1801 3e Avenue Val-d'Or j9p5k1 Centre d'affaires le Mesnil 1170, boul. LeBourgneuf Québec G2K 2E3 Centre de commerce mondial de Montréal 380, rue Saint-Antoine Ouest, bureau 1100 Montréal H2Y 3X7 Centre Manicouagan 600 boul.