Magna Mater in Latin Inscriptions Author(S): A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Dominus Muntanus". Mascula/Khenchela's Epigraph and the History of a Blunder

"Dominus Muntanus". Mascula/Khenchela's epigraph and the history of a blunder Alessandro Rossi ["Ager Veleias", 3.05 (2008)] Memoriae Peter Brock Toronto University (Thank You, professor …) 1. INTRODUCTION [1] Towards the end of IV century C.E. Basil of Caesarea explains in a long letter [2], focusing on the issue of baptism validity, whether celebrated by heretics and schismatics, that: The Pepuzans, then, are obviously heretical. For they have blasphemed against the Holy Spirit by unlawfully and shamelessly attributing the name of Paraclete to Montanus and Priscilla. They are condemned, therefore, either because they make men divine, or because they insult [3] the Holy Spirit by comparing him to men, and are thus liable to eternal condemnation because blasphemy against the Holy Spirit is unforgivable [4]. What basis to be accepted, then does the baptism have of these who baptize into the Father and the Son and Montanus or Priscilla? Such an interesting notice, about the occurred identification on the liturgical level between the Cataphrygians prophets and the Paraclet, should be submitted to critics considering both the polemical pattern in which it is included, and the characteristics of the polemic itself. Discussing on the difference between baptism either officiated by heretics, unacceptable for him, or officiated by schismatics (i.e. extra ecclesiam officiators just due to discipline, and not due to doctrinal dissensions), or during illegal meetings, Basil classifies Pepuzans, this term clearly used here as synonymous of Cataphrygians/Montanists, as heretic. The baptismal formula ascribed to them, even if preserving the trinitarian form, substitutes the name of the Spirit with the name of one out of the two prophets. -

Principaux Sites Romains

Un dossier de www.anticopedie.fr Principaux sites romains Albanie Butrinti (Buthrote) thermes Albanie Durrës (Dyrrachium) amphitheatre Algérie Abiot-Arab (oued), Babar el Slanis aqueduc Algérie Annaba (Hippone ou Hippo Regius) aqueduc, Thermes du Sud monuments, thermes Algérie Baghai (plaine) aqueduc Algérie Batna aqueduc Algérie Béjaia Saldae aqueduc Algérie Belezma (plaine) aqueduc Algérie Bélimour aqueduc Algérie Beni Mélek aqueduc Algérie Bordj-Zembia aqueduc Algérie Castellum Tingitanum aqueduc Algérie Chateaudun (plaine) aqueduc Algérie Cherchell (anc. Césarée de amphitheatre, Maurétanie) aqueduc, monuments Algérie Constantine (Cirta) aqueduc, monuments Algérie Djemila (Cuicul) aqueduc, Thermes de Commode monuments, thermes Algérie Djidgeli Igilgili aqueduc Algérie El Hamamet aqueduc Algérie Guelma (Calama) monument, theatre Algérie Guert-Gasses aqueduc Algérie Gunugu aqueduc Algérie Lambèse (Lambaesis) amphitheatre, monuments Algérie Macomades aqueduc Algérie Mahmel (plateau) aqueduc Algérie Mascula aqueduc Algérie Mellagou aqueduc Algérie Ouled Dahman aqueduc Algérie Perigotville aqueduc Algérie Rauzazus aqueduc Algérie Ruiscade aqueduc Algérie Sbikkra (plaine) aqueduc Algérie Sétif aqueduc Algérie Sidi Hamar aqueduc Algérie Sigus Siga aqueduc Algérie Skikda Ruisacde aqueduc Algérie Stora aqueduc Algérie Tamagra aqueduc Algérie Tebessa Thevestis amphitheatre, Temple de Minerve, arc de Caracalla aqueduc, monuments Algérie Tenes aqueduc Algérie Tiddis thermes Petits et grands thermes Algérie Tigava aqueduc Algérie Tiklat Tubusuptu -

Reexaming Heresy: the Donatists

Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II Volume 11 Article 9 2006 Reexaming Heresy: The onD atists Emily C. Elrod Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Elrod, Emily C. (2006) "Reexaming Heresy: The onD atists," Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II: Vol. 11 , Article 9. Available at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives/vol11/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Elrod: Reexaming Heresy 42 Historical Perspectives March 2006 Reexamining Heresy 43 Reexamining Heresy: The Donatists sure to bear upon the clergy,” so as “to render the laity leaderless, and . bring about general apostasy.”5 The clergy were to hand over Scriptures to the authori- Emily C. Elrod ties to be burnt, an act of desecration that became On the first day of June in A.D. 411, Carthage, two known by the Donatists as the sin of traditio. Bishops hostile groups of Christians faced off in the summer who committed this sin had no spiritual power and heat to settle their differences. They met at the mas- 1 became known as traditores; Mensurius, the Bishop of sive Baths of Gargilius (Thermae Gargilianiae). On Carthage who died in 311, stood accused of traditio. -

Thesis-1980-E93l.Pdf

LAMBAESIS TO THE REIGN OF HADRIAN By DIANE MARIE HOPPER EVERMAN " Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma December, 1977 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS July 25, 1980 -n , ,111e.5J s LAMBAESIS TO THE REIGN OF HADRIAN Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College ii 10S2909 PREFACE Lambaesis was a Roman Imperial military fortress in North Africa in the modern-day nation of Algeria. Rome originally acquired the territory as a result of the defeat of Carthage in the Punic Wars. Expansion of territory and settlement of surplus population were two ideas behind its Romanization. However, North Africa's greatest asset for becoming a province was its large yield of grain. This province furnished most of the wheat for the empire. If something happened to hinder its annual production level then Rome and its provinces would face famine. Unlike most instances of acquiring territory Rome did not try to assimilate the native transhumant population. Instead these inhabitants held on to their ancestral lands until they were forcibly removed. This territory was the most agriculturally productive; unfortunately, it was also the area of seasonal migration for the native people. Lambaesis is important in this scheme because it was the base of the solitary legion in North Africa, the III Legio Augusta. After beginning in the eastern section of the province just north of the Aures Mountains the legion gradually moved west leaving a peaceful area behind. The site of Lambaesis was the III Legio Augusta's westernmost fortress. -

Soldiers and Stelae: Votive Cult and the Roman Army in North Africa

Matthew M. McCarty Soldiers and Stelae: Votive Cult and the Roman Army in North Africa Introduction In the study of networks in the ancient world, the diffusion of cults plays an especially important role in understanding how such networks moved not just people and objects, but also ideas; how worldviews and façons de penser could be spread, could impact each other, and create cultural transformations extending beyond superstructure and veneer. Exploring the full depth of such cultural transformations requires two steps: first, establishing the webs which allowed such transmissions of ideas, and second, studying the reception and adaptation of the moving ideas. This paper will focus on the former, and will explore the mechanisms by which ideological connectivity was created. In so doing, it will look not at networks on the “global” scale, but instead at those networks essential to the maintenance of the Roman Empire, those smaller, inter-provincial systems of exchange. In order to tackle this problem, I will examine the spread of one particular cult - that of Saturn - through one particular part of North Africa - the military zone north of the Aurès. The worship of Saturn was a phenomenon that was particularly pronounced in Africa, from Mauretainia to eastern Proconsularis. In my examination, I will dispel at least two myths born of French colonialist scholarship which maintain a wide degree of currency: that of the cult of Saturn as “pan-African,” tied to African identity, and that of the cult as primarily a non-military, peasant cult 1. My argument is simple: that Rome created the networks which allowed even the small-scale spread of ideas in a manner that had not been seen before, and, in the case of the cult of Saturn in Africa, that the mechanism which caused the diffusion of the cult was the movement of the military and its recruitment patterns 2. -

Leszek Mrozewicz Flavian Urbanisation of Africa

Leszek Mrozewicz Flavian Urbanisation of Africa Studia Europaea Gnesnensia 7, 201-232 2013 LESZEK Mrozewicz, Flavian Urbanisation of Africa Studia Europaea Gnesnensia 7/2013 ISSN 2082–5951 Leszek Mrozewicz (Gniezno) FLAVIAN URBANIsatIon of AFRICA Abstract The article is concerned with urbanisation processes in Roman Africa, initiated by the Flavian dynasty (69–96). Emperor Vespasian and his successors focused their at- tention primarily on Africa Proconsularis. The new cities they created — colonies and municipia — were to perform an important strategic role, i.e. protect the territories of Africa Proconsularis against the southern tribes. With the great private latifundia and imperial domains, the province played a significant role in supplying the city of Rome with grain. Also, from the point of view of the state, the undertakings meant internal consolidation of the province. Key words Imperium Romanum, Africa, Flavians, urbanisation, Romanization, colonies, mu- nicipia 201 Studia Europaea Gnesnensia 7/2013 · people and places Throughout the last half-century of studies of the Roman North Africa1, it has become an established notion in science that the reign of the Flavian dynasty was a decisive turning point in its history2, and rightly so. This break- through embraced all areas of life, while the nature of the transformation is best reflected by the view that it was only thanks to the Flavians that Africa became fully Roman3. What is more, this is accompanied by the well-founded thesis that without the achievements of the Flavians, the great prosperity of the Flavian provinces in the 2nd–3rd centuries would not have been possible: their successors reaped what the Flavians had sowed4. -

The Military and Colonial Destruction of the Roman Landscape of North Africa, 1830–1900 History of Warfare

The Military and Colonial Destruction of the Roman Landscape of North Africa, 1830–1900 History of Warfare VOLUME 98 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hw The Military and Colonial Destruction of the Roman Landscape of North Africa, 1830–1900 By Michael Greenhalgh LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Delamare’s view of the French occupying Sétif, housed in tents, and with Roman ruins all around, including a cistern in the foreground, and the late antique walls to the rear. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Greenhalgh, Michael. The military and colonial destruction of the Roman landscape of North Africa, 1830–1900 / by Michael Greenhalgh. pages cm. — (History of warfare ; volume 98) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-24840-3 (hardback : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-90-04-27163-0 (e-book) 1. Classical antiquities—Destruction and pillage—Algeria—History—19th century. 2. Algeria—Antiquities, Roman. 3. France—Colonies—Algeria. 4. Algeria—History—1830–1962 I. Title. DT281.G74 2014 939’.703—dc23 2014007083 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual ‘Brill’ typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, ipa, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1385-7827 isbn 978 90 04 24840 3 (hardback) isbn 978 90 04 27163 0 (e-book) Copyright 2014 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill nv incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Nijhoff, Global Oriental and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Roman Ludi Saeculares from the Republic to Empire

Roman Ludi Saeculares from the Republic to Empire by Susan Christine Bilynskyj Dunning A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto © Susan Christine Bilynskyj Dunning 2016 Roman Ludi Saeculares from the Republic to Empire Susan Christine Bilynskyj Dunning Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics University of Toronto 2016 Abstract This dissertation provides the first comprehensive analysis of the Roman Ludi Saeculares, or “Saecular Games”, from their mythic founding in the sixth century bce until their final celebration in 248 ce. The Ludi Saeculares were a series of religious celebrations held at Rome every saeculum (“age”, “generation”), an interval of 100 or 110 years. The argument contains two major threads: an analysis of the origins and development of the Ludi Saeculares themselves, and the use of the term saeculum in imperial rhetoric in literary, epigraphic, and numismatic sources from early Republic to the fifth century ce. First, an investigation into Republican sacrifices that constitute part of the lineage of the Ludi Saeculares reveals that these rites were in origin called “Ludi Tarentini”, and were a Valerian gentilician cult that came under civic supervision in 249 bce. Next, it is shown that in his Saecular Games of 17 bce, Augustus appropriated the central rites of the Valerian cult, transforming them into “Ludi Saeculares” through a new association with the concept of the saeculum, and thereby asserting his role as restorer of the Republic and founder of a new age. The argument then turns to the development of saeculum rhetoric throughout the imperial period, intertwined with the history of the Ludi Saeculares. -

An Economic History of Rome Second Edition Revised

An Economic History of Rome Second Edition Revised Tenney Frank Batoche Books Kitchener 2004 Originally published in 1927. This edition published 2004 Batoche Books Limited [email protected] Contents Preface ...........................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1: Agriculture in Early Latium.........................................................................6 Chapter 2: The Early Trade of Latium and Etruria .....................................................14 Chapter 3: The Rise of the Peasantry ..........................................................................26 Chapter 4: New Lands For Old ...................................................................................34 Chapter 5: Roman Coinage .........................................................................................41 Chapter 6: The Establishment of the Plantation..........................................................52 Chapter 7: Industry and Commerce ............................................................................61 Chapter 8: The Gracchan Revolution..........................................................................71 Chapter 9: The New Provincial Policy........................................................................78 Chapter 10: Financial Interests in Politics ..................................................................90 Chapter 11: Public Finances......................................................................................101 -

Spatial Configuration Analysis Via Digital Tools of the Archeological Roman Town Timgad, Algeria

Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry Vol. 21, No 1, (2021), pp. 71-84 Open Access. Online & Print. www.maajournal.com DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4284429 SPATIAL CONFIGURATION ANALYSIS VIA DIGITAL TOOLS OF THE ARCHEOLOGICAL ROMAN TOWN TIMGAD, ALGERIA Abdelhalim Assassi* and Ammar Mebarki Institute of Architecture and Urbanism, University of Batna 1, Algeria Received: 28/10/2020 Accepted: 08/11/2020 *Corresponding author: Abdelhalim Assassi ([email protected]) ABSTRACT In this research project, we studied the ancient Timgad site which has been classified on the World Heritage List of Humanity by UNESCO, in order to understand quantitatively and digitally what was its urban and architectural spatial configuration as no earlier studies were made about this archeological site. The approach to this important question was the space syntax method via its digital tools applications, such as Depthmap and Agraph. Using these software programs and quantitative metrics, it was possible to identify elements that lead us to distinguish between the spatial properties within the urban site related to access, flow, individual behaviour, and the amenities inside of an average building, with considerations which are related to accessibility, movement, and way of life. These findings lead us to assess the spatial archeological value. Valuable elements to the architects, urbanists, and archaeologists are related to the understanding of the social domestic life found through the excavated archeological buildings within the framework of human anthropology. KEYWORDS: Archaeological Town Planning, Roman Town, Digital Tools, Timgad, Space Syntax, Depthmap, Agraph. Copyright: © 2021. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License. -

Flavian Urbanisation of Africa

LESZEK MROZEWICZ, FLAVIAN URBANISATION OF AFRICA STUDIA EuROPAEA GNESNENSIA 7/2013 ISSN 2082–5951 Leszek Mrozewicz (Gniezno) FLAVIAN URBANISATION OF AFRICA Abstract The article is concerned with urbanisation processes inR oman Africa, initiated by the Flavian dynasty (69–96). Emperor Vespasian and his successors focused their at- tention primarily on Africa Proconsularis. The new cities they created — colonies and municipia — were to perform an important strategic role, i.e. protect the territories of Africa Proconsularis against the southern tribes. With the great private latifundia and imperial domains, the province played a significant role in supplying the city ofR ome with grain. Also, from the point of view of the state, the undertakings meant internal consolidation of the province. Key words Imperium Romanum, Africa, Flavians, urbanisation, Romanization, colonies, mu- nicipia 201 STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 7/2013 · PEOPLE AND PLACES Throughout the last half-century of studies of the Roman North Africa1, it has become an established notion in science that the reign of the Flavian dynasty was a decisive turning point in its history2, and rightly so. This break- through embraced all areas of life, while the nature of the transformation is best reflected by the view that it was only thanks to the Flavians that Africa became fully Roman3. What is more, this is accompanied by the well-founded thesis that without the achievements of the Flavians, the great prosperity of the Flavian provinces in the 2nd–3rd centuries would not have been possible: their successors reaped what the Flavians had sowed4. Without going into too much detail, one should also recognise the rationality of the postulate to set apart the Flavian period in the history of Roman Africa as an era in its own right5. -

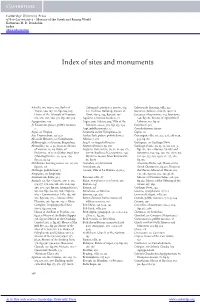

Index of Sites and Monuments

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-00230-1 - Mosaics of the Greek and Roman World Katherine M. D. Dunbabin Index More information Index of sites and monuments Acholla, 103, 104–5, 295; Baths of Colonnade, porticoes, 179–80, 304 Cabezón de Pisuerga, villa, 322 Trajan, 104, 107, 111, figs.104, 105; n.3; Triclinos Building, mosaic of Caesarea (Judaea), church, 196 n.19 House of the Triumph of Neptune, Hunt, 183–4, 234, figs.196, 197 Caesarea (Mauretania), 124; fountains, 105, 106, 280, 288, 310, figs.106, 309 Aquileia, Christian basilicas, 71 246, fig.261; Mosaic of Agricultural Agrigentum, 130 Argos, 299; Odeion, 304; Villa of the Labours, 117, fig.121 Ai Khanoum, palace, pebble mosaics, Falconer, 220–2, 305, figs.233, 234 Caminreal, 318 17 Arpi, pebble mosaics, 17 Camulodunum, 89–90 Aigai, see Vergina Arsameia on the Nymphaios, 30 Capsa, 117 Ain-Témouchent, 323 n.31 Arslan Tash, palace, pebble floor, 5 Carranque, villa, 155, 272, 276, 286 n.29, Alcalá de Henares, see Complutum Athens, 7, 271 323, fig.162 Aldborough, see Isurium Brigantum Augst, see Augusta Raurica Cartagena, see Carthago Nova Alexandria, 22–4, 32, 274 n.25; Mosaic Augusta Raurica, 79, 280 Carthage, Punic, 20, 33, 53, 101, 102–3, of warrior, 23, 24; Palace of Augusta Treverorum, 79, 81, 82, 94, 271, figs.101, 102; – Roman, Vandal and Ptolemies, 26 n.25; Shatby, Stag Hunt 317–18; Basilica of Constantine, 246; Byzantine, 103, 104, 107, 125, 127 n. 66, (Hunting Erotes), 20, 23–4, 254, Mysteries mosaic from Kornmarkt, 128, 130, 137, 138, 139 n.21, 257, 280, figs.22, 23, 24 82, fig.85