1 'A Contrapuntal-Harmonic-Orchestral Monster'? Karol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Join the National Philharmonic in a Triumphant

West End Off-Broadway United States International Entertainment Log In Re Washington, DC Sections Shows Chat Boards Jobs Students Video Industry Insider Join the National Philharmonic In a Hot Stories BroadwayWorld TV Triumphant Celebration of Poland's 100th Anniversary of Independence Complete Casting Announced for HOW TO by BWW News Desk May. 23, 2018 Tweet Share SUCCEED at the Kennedy Center TV Exclusive: Florida State Universi The National Philharmonic ends its 2017-2018 Southern Heat to Broadway S season at The Music Center at Strathmore with a musical celebration, "100th Anniversary of Poland's Independence," on Saturday, June 2 at 8 p.m. at the Concert Hall at the Music Center at Parris, Breckenridge, & More Strathmore. Conducted by world-renowned Join Drew Gehling in DAVE at Arena Stage Polish Maestro Miroslaw Jacek Baszczyk, the 10 DAYS TO GO CLICK HERE TO V concert will feature music composed by LIVE UPDATE: Poland's greatest musicians, performed by SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS or ME some of today's leading vocalists and musicians. for Best Musical... The performance will commence with an introduction by the Ambassador of Poland, Mosaic's Third Season Concludes With Epic World Piotr Wilczek. The 100th anniversary of Poland has signicant meaning for The National Premiere Starring Hadi Philharmonic, which is led by Polish-born Music Director and Conductor Piotr Gajewski. Tabbal One of The National Philharmonic's veteran artists, Brian Ganz-who will perform at the Polish celebration concert-is also a frequent performer of Frédéric Chopin, beginning a quest in 2011 to perform all of the great Polish composer's works. -

Tadeusz Baird. the Composer, His Work, and Its Reception

Tadeusz Baird. The Composer, His Work, and Its Reception Eastern European Studies in Musicology Edited by Maciej Gołąb Editorial board Mikuláš Bek (Brno) Gražina Daunoravi ien (Vilnius) Luba Kyjanovska (Lviv) Mikhail Saponov (Moscow) Adrian Thomas (Cardiff) László Vikárius (Budapest) Volume 17 Eastern European Studies Barbara Literska in Musicology Edited by Maciej Gołąb Editorial board Mikuláš Bek (Brno) Gražina Daunoravi ien (Vilnius) Luba Kyjanovska (Lviv) Mikhail Saponov (Moscow) Tadeusz Baird. The Composer, His Adrian Thomas (Cardiff) László Vikárius (Budapest) Work, and Its Reception Volume 17 Translated by John Comber Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliograe; detailed bibliographic data is available online at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. The Publication is funded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Re- public of Poland as a part of the National Programme for the Development of the Humanities in 2017-2018, project number 21H 16 0024 84. This publication re- ects the views only of the author, and the Ministry cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Printed by CPI books GmbH, Leck ISSN 2193-8342 ISBN 978-3-631-80284-7 (Print) E-ISBN 978-3-631-80711-8 (E-PDF) E-ISBN 978-3-631-80712-5 (EPUB) E-ISBN 978-3-631-80713-2 (MOBI) DOI 10.3726/b16420 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 unported license. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

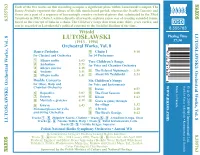

Lutosławski’S Output

CMYK N Each of the five works on this recording occupies a significant place within Lutosławski’s output. The AXOS Dance Preludes represent the climax of his folk music-based period, whereas the Double Concerto and Grave are a part of a sequence of increasingly creative orchestral pieces that culminated in the Third Symphony in 1983. Chain I, written directly afterwards, explores a new way of creating extended forms, 8.555763 based on the concept of links in a chain. The Children’s Songs date from some thirty years earlier, and DDD can be regarded as Lutosławski’s political response to the Socialist Realism of the time. 8.555763 Witold LUTOS LUTOSŁAWSKI Playing Time (1913 - 1994) 57:34 Orchestral Works, Vol. 8 Ł Dance Preludes 0 Chain I 9:18 AW for Clarinet and Orchestra for 14 Performers 1 Allegro molto 1:03 Two Children’s Songs 8 Vol. SKI: Works, Orchestral 2 Andantino 2:35 for Voice and Chamber Orchestra 3 Allegro giocoso 1:18 4 Andante 3:11 ! The Belated Nightingale 2:39 5 Allegro molto 1:41 @ About Mr Tralalinski 2:24 Double Concerto Six Children’s Songs for Oboe, Harp and for Voice and Instruments www.naxos.com Made in Canada. Booklet Notes in English • Kommentar auf Deutsch h Chamber Orchestra # Dance 0:57 & 6 Rapsodico 5:07 $ The Four Seasons 2:08 g SKI: Orchestral Works, Vol. 8 Vol. SKI: Works, Orchestral 7 Dolente 6:54 % Kitten 1:43 2003 HNH International Ltd. 8 Marziale e grotesco 6:19 ^ Grzes is going through AW the village 1:32 Ł 9 Grave 5:43 Metamorphoses for Cello & ABrook 2:20 and String Orchestra * The Bird’s Gossips -

The Polish Pianist Artur Hermelin

M u z y k a l i a XIII · Judaica 4 The Polish Pianist Artur Hermelin H a n n a P a l m o n Introduction For many years, I knew about my late relative - the pianist Artur Hermelin - only this: that he grew up in Lwow (called Lemberg when he was born there in 1901); that he was a child prodigy; and that as a piano soloist he toured Europe with orchestras and gave recitals - some of which were broadcasted by the Polish Radio. I also knew that Artur perished in the Holocaust. When my father told me that, his eyes revealed how much he was still missing his cousin Artur, who had been one year older than him; that was 30 years after Artur’s tragic death, when I was still a child; it was far beyond my grasp, and it still is. We had an old small photo of Artur as a very young boy, hugging a big accordion and giving the camera a warm smile. During my recent attempts to collect details about Artur’s 41 years of life – I’ve read that Artur was among the musicians who were forced to perform music for the Nazis in the ghetto of Lwow and later in the labor camp; hundreds of thousands of Jews - Artur and his relatives among them - were murdered at the ghetto of Lwow and at its notorious Janowska camp, or transported from the ghetto or the camp to concentration camps, in the years 1941-1943. May the memory of the victims be blessed. -

Musikgeschichte in Mittel- Und Osteuropa

Musikgeschichte in Mittel- und Osteuropa Musikgeschichte in Mittel- und Osteuropa Mitteilungen der internationalen Arbeitsgemeinschaft an der Universit¨at Leipzig Heft 10 in Zusammenarbeit mit den Mitgliedern der internationalen Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur¨ die Musikgeschichte in Mittel- und Osteuropa an der Universit¨at Leipzig herausgegeben von Helmut Loos und Eberhard M¨oller Redaktion Hildegard Mannheims Gudrun Schr¨oder Verlag Leipzig 2005 Gedruckt mit Unterstutzung¨ des Beauftragten der Bundesregierung fur¨ Angelegenheiten der Kultur und der Medien c 2005 by Gudrun Schr¨oder Verlag, Leipzig Redaktion und Satz: Hildegard Mannheims Kooperation: Rhytmos Verlag, PL 61-606 Pozna´n,Grochmalickiego 35/1 Alle Rechte, Nachdruck, auch auszugsweise, nur mit ausdrucklicher¨ Genehmigung des Verlags. Printed in Poland ISBN 3-926196-45-9 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort . IX Briefkorrespondenzen Vladimir Gurewitsch Der Briefwechsel von Jacob von St¨ahlin . 1 Urve Lippus Elmar Arro's letters to Karl Leichter . 12 Vita Lindenberg J^azeps V^ıtols (Wihtol) Briefe aus Riga, Lub¨ eck und Danzig an Irena, Narvaite (1940{1947) . 22 Jur¯ ate_ Burokaite_ Briefe von Mikalojus Konstantinas Ciurlionisˇ und ande- ren Musikern aus Leipzig nach Litauen (1901{1924) . 27 Ma lgorzata Janicka-S lysz The Letters of Grazyna_ Bacewicz and Vytautas Bace- viˇcius . 32 Ma lgorzata Perkowska-Waszek The letters of Ignacy Jan Paderewski as a source of knowledge concerning cultural relationships in Europe . 43 Karol Bula Gregor Fitelbergs Korrespondenz aus den Jahren 1945 bis 1953 . 57 Jelena Sinkewitsch Das Leipziger Konservatorium in den Briefen von My- kola Witalijowytsch Lyssenko (1867{1869) . 63 Luba Kyyanovska Die Briefe von Vasyl Barvins'kyj aus Prag als Spiegel des Musiklebens vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg (1905{1914) 72 Marianna Kopitsa Die neuen quellenkundlichen Studien in der Ukraine im Spiegel des epistolaren Erbes von Reinhold Glier und Boris Lyatoschinski . -

SHOSTAKOVICH Violin Concertos Nos

SHOSTAKOVICH Violin Concertos Nos. 1 and 2 Ilya Kaler, Violin Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra (Katowice) Antoni Wit, Conductor Dmitry Shostakovich (1 906-75) Violin Concertos Nos 1 & 2 Censured by Stalin, feted by Khruschev, celebrated by the world, a child of Tsarist Petersburg schooled by the first Leninists, public rhetorician, private soliloquiser: how will history choose to remember Shostakovich? As a chronicler of events epic and tragic, dimensions grotesque and satirical, perspectives elegiac and sentimental. As an essayer, a vivid essayer, of moods and confessions, of emotional discord and harmony. As a man, a genius, of destiny. Boris Tischenko, one of his students: "Our generation grew up on his music, and with his name on our lips. So our hearts would miss a beat when he took off his spectacles to clean them and we caught a glimpse of him, like a knight without armour, close to us, defenceless. The influence of his personality was so great that one began oneself to change, to become ashamed of one's insignificance, one's ineptitude, one's lack of understanding. That such a man lived has made the world a much finer place. We must all learn from him, and not from his music alone". As a human being of profound spiritual bitterness and disillusionment. Testament, the alleged memoirs (New York 1979): "Looking back I see nothing but ruins, only mountains of corpses ... There were no particularly happy moments in my life, no great joys. It was grey and dull and it makes me sad to think about it. It saddens me to admit it, but it's the truth, the unhappy truth". -

Polish Musicians in the Concert Life of Interwar Paris: Short Press Overview and Extensive Bibliographic Guide1

Polish Musicians in the Concert Life of Interwar Paris: Short Press Overview and Extensive Bibliographic Guide1 Renata Suchowiejko ( Jagiellonian University, Kraków) [email protected] The 20-year interwar period was a crucial time for Polish music. After Poland regained independence in 1918, the development of Polish musical culture was supported by government institutions. Infrastructure serving the concert life and the education system considerably improved along with the development of mass media and printing industries. International co-operation also got reinvigorated. New societies, associations and institutions were established to promote Polish culture abroad. And the mobility of musicians considerably increased. At that time the preferred destination of the artists’ rush was Paris. The journeys were taken mostly by young musicians in their twenties or thirties. Amongst them were instrumentalists, singers and directors who wished to improve their performance skills and to try their skills before the public of concert halls. Composers wanted to taste the musical climate of the metropolis and to learn the latest trends in music of that time. They strongly believed that 1. This paper has been prepared within the framework of the research programme Presence of Polish Music and Musicians in the Artistic Life of Interwar Paris, supported from the means of the National Science Centre, Poland, OPUS programme, under contract No. UMO-2016/23/B/ HS2/00895. The final effect of the project is the publication of a study Muzyczny Paryż à la polonaise w okresie międzywojennym. Artyści – Wydarzenia – Konteksty [Musical Paris à la polonaise In the Interwar Period: Artists – Events – Contexts] by Renata Suchowiejko, Kraków, Księgarnia Akademicka, 2020. -

Archives and Blank Spots: Scholarly Perspectives for Recovering Polish Music (1794–1945)

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology 19, 2019 @PTPN Poznań 2019, DOI 10.14746/ism.2019.19.6 MARCIN GMYS https://orcid.org/0000–0002–3844–0031 Institute of Musicology, Faculty of Arts, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Archives and blank spots: scholarly perspectives for recovering Polish music (1794–1945) ABSTRACT: In this article, the author tries to present the issue of blank spots in the history of Polish music since 1794 (the world premiere of Cud mniemany, czyli Krakowiacy i Górale [The supposed mirtacle, or Cracovians and highlanders] composed by Jan Stefani to the libretto of Wojciech Bogu- sławski is regarded as a symbolic beginning of national style in Polish music) up to the end of the Se- cond World War. It was a great period in history when Poland twice did not exist as a state (between 1795 and 1918 and between 1939 and 1945). At the beginning the attention is drawn to the Polish music in the nineteenth century. Author describes new discoveries such as the Second Piano Quintet in E flat Major (with double bass instead of second cello) by Józef Nowakowski (Chopin’s friend), and String Quartets op. 1 and monu- mental oratorio Passio Domini Nostri Jesu Christi by Józef Elsner who was Chopin’s teacher in the Conservatory of Music in Warsaw (Elsner’s Passio discovered at the end of the twentieth century is regarded now as the most outstanding religious piece in the history of Polish music in the nineteenth century). Among other works author also mentions romantic opera Monbar (1838) by Ignacy Feliks Dobrzyński and first opera of Stanisław Moniuszko Die Schweitzerhütte (about 1839) written to the German libretto during composer’s studies at Singakademie Berlin. -

Stanisław MONIUSZKO

Stanisław MONIUSZKO Overtures The Haunted Manor • Paria Halka • The Fairy Tale Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra • Antoni Wit Stanisław Stanisław Moniuszko (1819-1872) MONIUSZKO Overtures (1819-1872) Stanisław Moniuszko was the leading opera composer in written in 1841 to a libretto by the Polish poet, playwright Overtures Poland during the nineteenth century. His work, as and author Aleksander Fredro, who devised a farcical plot Lennox Berkeley once wrote, may be said to ‘bridge the concerning the comic adventures of a man looking for his 1 Bajka (The Fairy Tale) – Overture gap in Polish music between Chopin and Szymanowski’. one true love. Representative of its composer, the score (ed. Witold Rowicki) (1848) 13:26 Born in Ubiel, near Minsk, he began piano lessons with includes a dashing mazurka. his mother at the age of four. In 1827 he studied music Moniuszko’s first substantial piece for full orchestra, with August Freyer in Warsaw and completed his training the overture Bajka (The Fairy Tale) was written in Vilnius 2 Paria – Opera: Overture with Carl Friedrich Rungenhagen at the Berlin in May 1848. One of his few concert works, its fantasia- (ed. Grzegorz Fitelberg) (1859-69) 9:46 Singakademie (1837-1839). After returning to Poland, he overture character suggests affinities with orchestral tone- married and settled in Vilnius, earning his living as a piano poems of the period, such as those by Franz Liszt. 3 Halka – Opera: Overture teacher, organist and conductor of the theatre orchestra. Contrasting themes are interwoven to form an extended (ed. Grzegorz Fitelberg) (1848) 8:36 Moniuszko’s output includes seven Masses, several narrative. -

View Full Program and Program Notes

Sounds of PADEREWSKI Lecture-Recital October 14, 2018 | 7 PM Alfred Newman Recital Hall, USC Independence 2018 PADEREWSKI LECTURE-RECITAL Sounds of Independence: Music by Polish Composers of the Interwar Era Lecture by Dr. Lisa Cooper Vest FEATURING Bradley Bascon & Leonard Chong, violins Sérgio Coelho, clarinet Allan Hon, cello So-Mang Jeagal, piano Stephanie Jones, soprano Yun-Chieh ( Jenny) Sung, viola USC Chamber Singers with Dr. Jo-Michael Scheibe and Andrew Schultz, conductors Sunday, October 14, 2018 | 7:00 p.m. Alfred Newman Recital Hall University of Southern California Los Angeles, California Presented by the Polish Music Center at the USC Th ornton School of Music in celebration of 100 Years of Poland’s Independence Polish Music Center Composing the Nation: Intersections of Modernity and Tradition in Interwar Poland Lecture by Dr. Lisa Cooper Vest, USC Thornton School of Music • • • Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860-1941) HEJ, ORLE BIAŁY (1917) USC Chamber Singers Andrew Schultz, conductor | So-Mang Jeagal, piano Ludomir Różycki (1883-1953) KRAKOWIAK FROM THE BALLET PAN TWARDOWSKI (1920) ARR. MAREK ZEBROWSKI Bradley Bascon & Leonard Chong, violin Yun-Chieh (Jenny) Sung, viola | Allan Hon, cello Sergio Coelho, clarinet | So-Mang Jeagal, piano Aleksander Tansman (1897-1986) CINQ MÉLODIES (1927) Dans le secret de mon âme Hélas Sommeil Chats de gouttière Bonheur Stephanie Jones, soprano | So-Mang Jeagal, piano Józef Koffl er (1896-1944) DIE LIEBE/ MIŁOŚĆ (1931) Adagio Andante tranquillo Allegro moderato Tempo I Stephanie Jones, soprano | Sergio Coelho, clarinet Yun-Chieh (Jenny) Sung, viola | Allan Hon, cello Grażyna Bacewicz (1909-1969) STRING QUARTET NO. 1 (1938) Moderato Tema con variazioni Vivo Bradley Bascon & Leonard Chong, violin Yun-Chieh (Jenny) Sung, viola | Allan Hon, cello Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937) KURPIE SONGS OP. -

MAHLER Symphony No

MAHLER Symphony No. 9 Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra Michael Halisz, Conductor Gustav Mahler (1860 - 1911) Symphony No. 9 The great Viennese symphonic tradition found worthy successors in two composers of very different temperament and background, Anton Bruckner and GustavMahler. The latter, indeed, extended the form in an extraordinarywaythat has had afar-reaching effect on the courseof Western music, among otherthings creating a symphonic form that included in it the tradition of song in a varied tapestry of sound particularlyaptforatwentiethcenturythat has found in Mahler's work a reflection of its own joys and sorrows. Mahler was to express succinctly enough his position in the world. He saw himself as three times homeless, a native of Bohemia in Austria, an Austrian among Germans and a Jew throughout the whole world. The second child of his parents, and the first of fourteen to survive, he was born in Kaliste in Bohemia in 1860. Soon afterhis birth hisfamilymoved toJihlava, where hisfather, by hisown very considerable efforts, had raised himself from being little more than a pedlar, with a desire for intellectual self-im~rovement,to the ownership of a tavern and distillery. Mahler's musical abilitiesbere developed first in ~ihlava,before a brief period of schoolingin Prague, which ended unhappily, andalatercourseof study attheConse~atorvin Vienna, where heturnedfromthe pianotocompositionand, as a necessary cdro~~ary,to conducting. It was as a conductor that Mahler made his career, at first at a series of provincial opera-houses, then in Prague, Budapest and Hamburg, before moving toapositionof the highestdistinctionof all, when, in 1897, he becameKapellmeister of the Vienna Court Opera, two months after his baptism as a Catholic, a necessary preliminary.