SHOSTAKOVICH Violin Concertos Nos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(1; . -;-."':::With, Say, Itzhak ~ ...•

PROKOFIEVViolin concertos nO.1 in D major op.19 & no.2 . in G minor op.63. Sonata in C major for two violins op.56* [ Pavel Berman, Anna find the effect here, especially Tifu* (violin) Orchestra in the Second Concerto, I della Svizzera ltaliana/ initially disorientating. Yet Andrey Boreyko to hear Prokofiev's super- DYNAMIC CD5 676 virtuoso writing emerging Indianapo!is prizewinner wìth such blernishless poìse Pavel Berman brings and unforced eloquence comes freshness and eloquence as a welcome relìef compared to Prokofiev to the claustrophobic intensity of most recorded accounts. When cornpared The Double Violin Sonata is .(1; . -;-."':::with, say, Itzhak also beautìfully played and . ~~~i,-""-.=...• Perlman's EMI record ed, with Prokofiev's - ' recording wìth lyrìcal genius well to the fore, ~ Gennadi JULlAN HAYLOCK Rozhdestvensky or Isaac Stern's Sony classìc with Eugene Orrnandy, the natural perspectives of this new version, where Pavel Berrnan's sweer-toned playing emerges seductively frorn the orchestrai ranks, are such that one couId almost be listening to different pieces. Subtle internai orchestrai detaìl is revealed (particularly in the First Concerto) that usuali)' lies concealed behind the solo image. The passages where Bcrrnan duets engagingl), with solo woodwind instrumenrs or harp feel more 'sinfonia concertante' than concerto proper. The effect, especially rowards the end of the finale, is often magical, as Berman's silvery purity becomes enveloped in a pulsating web of orchestrai sound. Those raised on classi c accounts from David Oistrakh (EMI),Kyung-Wha Chung (Dccca) or Shlorno Mintz (Deutsche Grammophon), in which one can hear and feel the contract ofbow on string or fingers on fingerboard, ma)' AUGUST 2011 THE STRAD 93 Rue St-Pierre 2 - 1003 Lausanne (eH) Te1. -

Join the National Philharmonic in a Triumphant

West End Off-Broadway United States International Entertainment Log In Re Washington, DC Sections Shows Chat Boards Jobs Students Video Industry Insider Join the National Philharmonic In a Hot Stories BroadwayWorld TV Triumphant Celebration of Poland's 100th Anniversary of Independence Complete Casting Announced for HOW TO by BWW News Desk May. 23, 2018 Tweet Share SUCCEED at the Kennedy Center TV Exclusive: Florida State Universi The National Philharmonic ends its 2017-2018 Southern Heat to Broadway S season at The Music Center at Strathmore with a musical celebration, "100th Anniversary of Poland's Independence," on Saturday, June 2 at 8 p.m. at the Concert Hall at the Music Center at Parris, Breckenridge, & More Strathmore. Conducted by world-renowned Join Drew Gehling in DAVE at Arena Stage Polish Maestro Miroslaw Jacek Baszczyk, the 10 DAYS TO GO CLICK HERE TO V concert will feature music composed by LIVE UPDATE: Poland's greatest musicians, performed by SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS or ME some of today's leading vocalists and musicians. for Best Musical... The performance will commence with an introduction by the Ambassador of Poland, Mosaic's Third Season Concludes With Epic World Piotr Wilczek. The 100th anniversary of Poland has signicant meaning for The National Premiere Starring Hadi Philharmonic, which is led by Polish-born Music Director and Conductor Piotr Gajewski. Tabbal One of The National Philharmonic's veteran artists, Brian Ganz-who will perform at the Polish celebration concert-is also a frequent performer of Frédéric Chopin, beginning a quest in 2011 to perform all of the great Polish composer's works. -

Download Booklet

557757 bk Bloch US 20/8/07 8:50 pm Page 5 Royal Scottish National Orchestra the Sydney Opera, has been shown over fifty times on U.S. television, and has been released on DVD. Serebrier regularly champions contemporary music, having commissioned the String Quartet No. 4 by Elliot Carter (for his Formed in 1891 as the Scottish Orchestra, and subsequently known as the Scottish National Orchestra before being Festival Miami), and conducted world première performances of music by Rorem, Schuman, Ives, Knudsen, Biser, granted the title Royal at its centenary celebrations in 1991, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra is one of Europe’s and many others. As a composer, Serebrier has won most important awards in the United States, including two leading ensembles. Distinguished conductors who have contributed to the success of the orchestra include Sir John Guggenheims (as the youngest in that Foundation’s history, at the age of nineteen), Rockefeller Foundation grants, Barbirolli, Karl Rankl, Hans Swarowsky, Walter Susskind, Sir Alexander Gibson, Bryden Thomson, Neeme Järvi, commissions from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Harvard Musical Association, the B.M.I. Award, now Conductor Laureate, and Walter Weller who is now Conductor Emeritus. Alexander Lazarev, who served as Koussevitzky Foundation Award, among others. Born in Uruguay of Russian and Polish parents, Serebrier has Ernest Principal Conductor from 1997 to 2005, was recently appointed Conductor Emeritus. Stéphane Denève was composed more than a hundred works. His First Symphony had its première under Leopold Stokowski (who gave appointed Music Director in 2005 and his first recording with the RSNO of Albert Roussel’s Symphony No. -

Tadeusz Baird. the Composer, His Work, and Its Reception

Tadeusz Baird. The Composer, His Work, and Its Reception Eastern European Studies in Musicology Edited by Maciej Gołąb Editorial board Mikuláš Bek (Brno) Gražina Daunoravi ien (Vilnius) Luba Kyjanovska (Lviv) Mikhail Saponov (Moscow) Adrian Thomas (Cardiff) László Vikárius (Budapest) Volume 17 Eastern European Studies Barbara Literska in Musicology Edited by Maciej Gołąb Editorial board Mikuláš Bek (Brno) Gražina Daunoravi ien (Vilnius) Luba Kyjanovska (Lviv) Mikhail Saponov (Moscow) Tadeusz Baird. The Composer, His Adrian Thomas (Cardiff) László Vikárius (Budapest) Work, and Its Reception Volume 17 Translated by John Comber Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliograe; detailed bibliographic data is available online at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. The Publication is funded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Re- public of Poland as a part of the National Programme for the Development of the Humanities in 2017-2018, project number 21H 16 0024 84. This publication re- ects the views only of the author, and the Ministry cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Printed by CPI books GmbH, Leck ISSN 2193-8342 ISBN 978-3-631-80284-7 (Print) E-ISBN 978-3-631-80711-8 (E-PDF) E-ISBN 978-3-631-80712-5 (EPUB) E-ISBN 978-3-631-80713-2 (MOBI) DOI 10.3726/b16420 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 unported license. -

1 'A Contrapuntal-Harmonic-Orchestral Monster'? Karol

1 ‘A Contrapuntal-Harmonic-Orchestral Monster’? Karol Szymanowski’s First Symphony in the Context of Polish and German Symphonic Tradition Stefan Keym Institute of Musicology, University of Leipzig [...] itwillbeasortofcontrapuntal-harmonic-orchestralmonster,andIamalready looking forward to seeing the Berlin critics leaving the concert hall with a curse on their livid lips when this symphony will be played at our concert.1 This statement by Karol Szymanowski, made in July 1906 in a letter to Hanna Klechniowska, has often been taken to prove the opinion that his Symphony No. 1 op. 15 (composed in 1906/07)2 is an ‘insincere’ work written mainly to demonstrate the technical mastery of the young composer and not to express his personal feelings and values.3 In fact, Szymanowski’s op. 15 was fateful: After its one and only performance by Grzegorz Fitelberg and the Filharmonia Warszawska on 26th March 1909,4 it disappeared comple- tely from the concert programmes. In contrast to Szymanowski’s Concert Overture op. 12 (1904–05) and to his Symphony No. 2 op. 19 (1909–10), the score of his First Symphony was never revised by the composer5 and remains unpublished up to now.6 On the other hand, commentaries by artists on their own works should not be taken too literally. In his statements on some other, more successful compositions, young Szymanowski also mentioned mainly technical aspects: for example, he called the final fugue of his Second Symphony a ‘terrible ma- chine’ with a ‘devilishly complicated’ thematic structure.7 He also provided the musicologists Henryk Opieński and Zdzisław Jachimecki with detailed de- scriptions of the formal structure of his Second Symphony and of his Second 5 6 Stefan Keym Piano Sonata op. -

Lutosławski’S Output

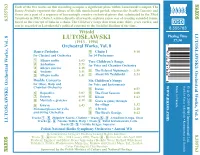

CMYK N Each of the five works on this recording occupies a significant place within Lutosławski’s output. The AXOS Dance Preludes represent the climax of his folk music-based period, whereas the Double Concerto and Grave are a part of a sequence of increasingly creative orchestral pieces that culminated in the Third Symphony in 1983. Chain I, written directly afterwards, explores a new way of creating extended forms, 8.555763 based on the concept of links in a chain. The Children’s Songs date from some thirty years earlier, and DDD can be regarded as Lutosławski’s political response to the Socialist Realism of the time. 8.555763 Witold LUTOS LUTOSŁAWSKI Playing Time (1913 - 1994) 57:34 Orchestral Works, Vol. 8 Ł Dance Preludes 0 Chain I 9:18 AW for Clarinet and Orchestra for 14 Performers 1 Allegro molto 1:03 Two Children’s Songs 8 Vol. SKI: Works, Orchestral 2 Andantino 2:35 for Voice and Chamber Orchestra 3 Allegro giocoso 1:18 4 Andante 3:11 ! The Belated Nightingale 2:39 5 Allegro molto 1:41 @ About Mr Tralalinski 2:24 Double Concerto Six Children’s Songs for Oboe, Harp and for Voice and Instruments www.naxos.com Made in Canada. Booklet Notes in English • Kommentar auf Deutsch h Chamber Orchestra # Dance 0:57 & 6 Rapsodico 5:07 $ The Four Seasons 2:08 g SKI: Orchestral Works, Vol. 8 Vol. SKI: Works, Orchestral 7 Dolente 6:54 % Kitten 1:43 2003 HNH International Ltd. 8 Marziale e grotesco 6:19 ^ Grzes is going through AW the village 1:32 Ł 9 Grave 5:43 Metamorphoses for Cello & ABrook 2:20 and String Orchestra * The Bird’s Gossips -

EDGAR MOREAU, Cellist

EDGAR MOREAU, cellist “Mr. Moreau immediately began to display his musical flair and his distinctive persona. His incredibly beautiful tone spoke directly to the heart and soul. Mr. Moreau established his credentials as a player of remarkable caliber. His intriguing presence, marvelously messy hair, and expressive face were all reflections of the inner poet.” —OBERON’S GROVE (NY) “This cello prodigy belongs in the family of the greatest artists of all time. The audience gave him an enthusiastic ovation in recognition of a divinely magical evening.” —LA PROVENCE ”He is just 20 years old, but for the past five years, this young musketeer of the bow has been captivating all of his audiences. He is the rising star of the French cello.” —LE FIGARO “Edgar Moreau captivates all those who hear him. Behind his boyish looks lies a performer of rare maturity. He is equally at ease in a chamber ensemble, as a soloist with orchestra or in recital, and his facility and pose are simply astounding.” —DIAPASON (Debut CD: “Play” ) European Concert Hall Organization’s 2016-2017 Rising Star 2015 Arthur Waser Foundation Award, in association with the Lucerne Symphony (Switzerland) 2015 Solo Instrumentalist of the Year, Victoires de la Musique Tchaikovsky Competition, 2011, Second Prize and Prize for Best Performance of the Commissioned Work First Prize, 2014 Young Concert Artists International Auditions Florence Gould Foundation Fellowship The Embassy Series Prize (Washington, DC) • The Friends of Music Concerts Prize (NY) The Harriman-Jewell Series Prize (MO) • The Saint Vincent College Concert Series Prize (PA) Chamber Orchestra of the Triangle Prize (NC) • University of Florida Performing Arts Prize The Candlelight Concert Society Prize (MD) YOUNG CONCERT ARTISTS, INC. -

The Polish Pianist Artur Hermelin

M u z y k a l i a XIII · Judaica 4 The Polish Pianist Artur Hermelin H a n n a P a l m o n Introduction For many years, I knew about my late relative - the pianist Artur Hermelin - only this: that he grew up in Lwow (called Lemberg when he was born there in 1901); that he was a child prodigy; and that as a piano soloist he toured Europe with orchestras and gave recitals - some of which were broadcasted by the Polish Radio. I also knew that Artur perished in the Holocaust. When my father told me that, his eyes revealed how much he was still missing his cousin Artur, who had been one year older than him; that was 30 years after Artur’s tragic death, when I was still a child; it was far beyond my grasp, and it still is. We had an old small photo of Artur as a very young boy, hugging a big accordion and giving the camera a warm smile. During my recent attempts to collect details about Artur’s 41 years of life – I’ve read that Artur was among the musicians who were forced to perform music for the Nazis in the ghetto of Lwow and later in the labor camp; hundreds of thousands of Jews - Artur and his relatives among them - were murdered at the ghetto of Lwow and at its notorious Janowska camp, or transported from the ghetto or the camp to concentration camps, in the years 1941-1943. May the memory of the victims be blessed. -

Musicweb International August 2020 RETROSPECTIVE SUMMER 2020

RETROSPECTIVE SUMMER 2020 By Brian Wilson The decision to axe the ‘Second Thoughts and Short Reviews’ feature left me with a vast array of part- written reviews, left unfinished after a colleague had got their thoughts online first, with not enough hours in the day to recast a full review in each case. This is an attempt to catch up. Even if in almost every case I find myself largely in agreement with the original review, a brief reminder of something you may have missed, with a slightly different slant, may be useful – and, occasionally, I may be raising a dissenting voice. Index [with page numbers] Malcolm ARNOLD Concerto for Organ and Orchestra – see Arthur BUTTERWORTH Johann Sebastian BACH Concertos for Harpsichord and Strings – Volume 1_BIS [2] Johann Sebastian BACH, Georg Philipp TELEMANN, Carl Philipp Emanuel BACH The Father, the Son and the Godfather_BIS [2] Sir Arnold BAX Morning Song ‘Maytime in Sussex’ – see RUBBRA Amy BEACH Piano Quintet (with ELGAR Piano Quintet)_Hyperion [9] Sir Arthur BLISS Piano Concerto in B-flat – see RUBBRA Benjamin BRITTEN Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings, etc._Alto_Regis [15, 16] Arthur BUTTERWORTH Symphony No.1 (with Ruth GIPPS Symphony No.2, Malcolm ARNOLD Concerto for Organ and Orchestra)_Musical Concepts [16] Paul CORFIELD GODFREY Beren and Lúthien: Epic Scenes from the Silmarillion - Part Two_Prima Facie [17] Sir Edward ELGAR Symphony No.2_Decca [7] - Sea Pictures; Falstaff_Decca [6] - Falstaff; Cockaigne_Sony [7] - Sea Pictures; Alassio_Sony [7] - Violin Sonata (with Ralph VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Violin Sonata; The Lark Ascending)_Chandos [9] - Piano Quintet – see Amy BEACH Gerald FINZI Concerto for Clarinet and Strings – see VAUGHAN WILLIAMS [10] Ruth GIPPS Symphony No.2 – see Arthur BUTTERWORTH Alan GRAY Magnificat and Nunc dimittis in f minor – see STANFORD Modest MUSSORGSKY Pictures from an Exhibition (orch. -

David Oistrakh ¨ E | Chausson | Shostakovich | Chausson | Rachmaninoff E | Pays Tributeto

LYDIA MORDKOVITCH PAYS TRIBUTE TO DAVID OISTRAKH Classics LOCATELLI | YSAY¨ E | CHAUSSON | SHOSTAKOVICH | RACHMANINOFF Pietro Antonio Locatelli Locatelli Antonio Pietro © Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Lydia Mordkovitch Pays Tribute to David Oistrakh Pietro Antonio Locatelli (1695–1764) Sonata, Op. 6 No. 7 ‘Au tombeau’* 15:16 in F minor • in f-Moll • en fa mineur Arranged for Violin and Piano by Eugène Ysaÿe 1 I Lento assai e mesto – Adagio in modo di recitativo – Recitativo ma più animato che prima – Risoluto 5:06 2 II Allegro moderato e con passione – 2:07 3 III Adagio 2:29 4 IV Cantabile. Tempo molto moderato – Maggiore – Con brio – Più largo – Lento 5:32 5 Caprice No. 23 ‘Il labirinto armonico’ 3:21 from L’arte del violino: XII concerti… con XXIV capricci ad libitum, Op. 3 for Solo Violin Facilis aditus, difficilis exitus Allegro moderato 3 Eugène Ysaÿe (1858–1931) Sonata, Op. 27 No. 2 14:26 in A minor • in a-Moll • en la mineur for Solo Violin To Jacques Thibaud 6 I Obsession. Prelude 2:50 7 II Malinconia 3:26 8 III Danse des ombres. Sarabande 5:12 9 IV Les Furies 2:55 Ernest Chausson (1855–1899) 10 Poème, Op. 25† 14:17 Arranged for Violin and Piano Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975) Sonata, Op. 134‡ 29:40 for Violin and Piano 11 I Andante 9:27 12 II Allegretto 6:20 13 III Largo – Andante – Largo 13:51 4 Serge Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) 14 Daisies§ 2:42 No. 3, ‘Margaritki’, from Six Songs, Op. 38 Arranged for Violin and Piano by Fritz Kreisler Lento TT 79:46 Lydia Mordkovitch violin Nicholas Walker piano* Marina Gusak-Grin piano† Clifford Benson piano‡ James Kirby piano§ 5 From the personal collection of Lydia Mordkovitch Lydia Mordkovitch, fourth from left, with students and professors, attending a class with David Oistrakh, right, in his room at the Moscow Conservatory Lydia Mordkovitch Pays Tribute to David Oistrakh A note from the performer I was present at a concert at the Composers’ I had the luck and privilege to study with the Union in Moscow, where David Fedorovich great Russian violinist David Oistrakh. -

Jascha Heifetz, David Oistrakh, Joseph Szigeti: Their Contributions to the Violin Repertoire of the Twentieth Century Jae Won (Noella) Jung

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Jascha Heifetz, David Oistrakh, Joseph Szigeti: Their Contributions to the Violin Repertoire of the Twentieth Century Jae Won (Noella) Jung Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC JASCHA HEIFETZ, DAVID OISTRAKH, JOSEPH SZIGETI: THEIR CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE VIOLIN REPERTOIRE OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY By Jae Won (Noella) Jung A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 Copyright © 2007 Jae Won (Noella) Jung All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Jae Won (Noella) Jung on March 2, 2007. ____________________________________ Karen Clarke Professor Directing Treatise ____________________________________ Jane Piper Clendinning Outside Committee Member ____________________________________ Alexander Jiménez Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my advisor, Professor Karen Clarke, for her guidance and support during my graduate study at FSU and I am deeply grateful for her advice and suggestions on this treatise. I would also like to thank the rest of my doctoral committee, Professor Jane Piper Clendinning and Professor Alexander Jiménez for their insightful comments. This treatise would not have been possible without the encouragement and support from my family. I thank my parents for their unconditional love and constant belief, my sister for her friendship, and my nephew Jin Sung for his precious smile. -

Polish Musicians in the Concert Life of Interwar Paris: Short Press Overview and Extensive Bibliographic Guide1

Polish Musicians in the Concert Life of Interwar Paris: Short Press Overview and Extensive Bibliographic Guide1 Renata Suchowiejko ( Jagiellonian University, Kraków) [email protected] The 20-year interwar period was a crucial time for Polish music. After Poland regained independence in 1918, the development of Polish musical culture was supported by government institutions. Infrastructure serving the concert life and the education system considerably improved along with the development of mass media and printing industries. International co-operation also got reinvigorated. New societies, associations and institutions were established to promote Polish culture abroad. And the mobility of musicians considerably increased. At that time the preferred destination of the artists’ rush was Paris. The journeys were taken mostly by young musicians in their twenties or thirties. Amongst them were instrumentalists, singers and directors who wished to improve their performance skills and to try their skills before the public of concert halls. Composers wanted to taste the musical climate of the metropolis and to learn the latest trends in music of that time. They strongly believed that 1. This paper has been prepared within the framework of the research programme Presence of Polish Music and Musicians in the Artistic Life of Interwar Paris, supported from the means of the National Science Centre, Poland, OPUS programme, under contract No. UMO-2016/23/B/ HS2/00895. The final effect of the project is the publication of a study Muzyczny Paryż à la polonaise w okresie międzywojennym. Artyści – Wydarzenia – Konteksty [Musical Paris à la polonaise In the Interwar Period: Artists – Events – Contexts] by Renata Suchowiejko, Kraków, Księgarnia Akademicka, 2020.