Print-At-Home Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(1; . -;-."':::With, Say, Itzhak ~ ...•

PROKOFIEVViolin concertos nO.1 in D major op.19 & no.2 . in G minor op.63. Sonata in C major for two violins op.56* [ Pavel Berman, Anna find the effect here, especially Tifu* (violin) Orchestra in the Second Concerto, I della Svizzera ltaliana/ initially disorientating. Yet Andrey Boreyko to hear Prokofiev's super- DYNAMIC CD5 676 virtuoso writing emerging Indianapo!is prizewinner wìth such blernishless poìse Pavel Berman brings and unforced eloquence comes freshness and eloquence as a welcome relìef compared to Prokofiev to the claustrophobic intensity of most recorded accounts. When cornpared The Double Violin Sonata is .(1; . -;-."':::with, say, Itzhak also beautìfully played and . ~~~i,-""-.=...• Perlman's EMI record ed, with Prokofiev's - ' recording wìth lyrìcal genius well to the fore, ~ Gennadi JULlAN HAYLOCK Rozhdestvensky or Isaac Stern's Sony classìc with Eugene Orrnandy, the natural perspectives of this new version, where Pavel Berrnan's sweer-toned playing emerges seductively frorn the orchestrai ranks, are such that one couId almost be listening to different pieces. Subtle internai orchestrai detaìl is revealed (particularly in the First Concerto) that usuali)' lies concealed behind the solo image. The passages where Bcrrnan duets engagingl), with solo woodwind instrumenrs or harp feel more 'sinfonia concertante' than concerto proper. The effect, especially rowards the end of the finale, is often magical, as Berman's silvery purity becomes enveloped in a pulsating web of orchestrai sound. Those raised on classi c accounts from David Oistrakh (EMI),Kyung-Wha Chung (Dccca) or Shlorno Mintz (Deutsche Grammophon), in which one can hear and feel the contract ofbow on string or fingers on fingerboard, ma)' AUGUST 2011 THE STRAD 93 Rue St-Pierre 2 - 1003 Lausanne (eH) Te1. -

Program Notes

NOTES ON THE PROGRAM Pro Musica March 23, 2017 Academy of St Martin in the Fields Aaron Copland (1900-1990) Quiet City Aaron Copland’s compositions are divided into three periods: the early jazz-inspired works, the severely avant-garde, and the “Americana” or populist style that produced his most beloved works such as Rodeo, Appalachian Spring, Lincoln Portrait, and Fanfare for the Common Man. While Quiet City of 1940 falls into Copland’s populist style, we should be cautious about that categorization causing us to miss the work’s purely musical qualities and genius. That said, we must recognize it as one of the most evocative pieces of Copland’s output. In this case, it paints a night in a sleepless city, presumably New York, Copland’s home. Based on Copland’s incidental music for Irwin Shaw’s failed play of the same name, Quiet City was premiered in 1941 by the Saidenberg Little Symphony in New York City. Copland himself commented that the work was “an attempt to mirror the troubled main character of Irwin Shaw’s play.” He also admitted that Quiet City “seems to have become a musical entity superseding the original reasons for its composition.” On Mozart and Shostakovich In light of the combination of Mozart and Shostakovich on this program, we offer the following thoughts: On the death of the American novelist Saul Bellow, The New York Times reported that Mr. Bellow once told a reporter that “for many years, Mozart was a kind of idol to me—this rapturous singing that’s always on the edge of sadness and melancholy and disappointment and heartbreak, but always ready for an outburst of the most delicious music.” One could say much of the same about the music of Shostakovich, thus pointing to the raison d’etre for combining these two composers on a program. -

2020-21 Season Brochure

2020 SEA- This year. This season. This orchestra. This music director. Our This performance. This artist. World This moment. This breath. This breath. 2021 SON This breath. Don’t blink. ThePhiladelphiaOrchestra MUSIC DIRECTOR YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN our world Ours is a world divided. And yet, night after night, live music brings audiences together, gifting them with a shared experience. This season, Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin and The Philadelphia Orchestra invite you to experience the transformative power of fellowship through a bold exploration of sound. 2 2020–21 Season 3 “For me, music is more than an art form. It’s an artistic force connecting us to each other and to the world around us. I love that our concerts create a space for people to gather as a community—to explore and experience an incredible spectrum of music. Sometimes, we spend an evening in the concert hall together, and it’s simply some hours of joy and beauty. Other times there may be an additional purpose, music in dialogue with an issue or an idea, maybe historic or current, or even a thought that is still not fully formed in our minds and hearts. What’s wonderful is that music gives voice to ideas and feelings that words alone do not; it touches all aspects of our being. Music inspires us to reflect deeply, and music brings us great joy, and so much more. In the end, music connects us more deeply to Our World NOW.” —Yannick Nézet-Séguin 4 2020–21 Season 5 philorch.org / 215.893.1955 6A Thursday Yannick Leads Return to Brahms and Ravel Favorites the Academy Garrick Ohlsson Thursday, October 1 / 7:30 PM Thursday, January 21 / 7:30 PM Thursday, March 25 / 7:30 PM Academy of Music, Philadelphia Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor Lisa Batiashvili Violin Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Garrick Ohlsson Piano Hai-Ye Ni Cello Westminster Symphonic Choir Ravel Le Tombeau de Couperin Joe Miller Director Szymanowski Violin Concerto No. -

PROGRAM NOTES Franz Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 in a Major

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Franz Liszt Born October 22, 1811, Raiding, Hungary. Died July 31, 1886, Bayreuth, Germany. Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major Liszt composed this concerto in 1839 and revised it often, beginning in 1849. It was first performed on January 7, 1857, in Weimar, by Hans von Bronsart, with the composer conducting. The first American performance was given in Boston on October 5, 1870, by Anna Mehlig, with Theodore Thomas, who later founded the Chicago Symphony, conducting his own orchestra. The orchestra consists of three flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 1 and 2, 1901, with Leopold Godowsky as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on March 19, 20, and 21, 2009, with Jean-Yves Thibaudet as soloist and Jaap van Zweden conducting. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on August 4, 1945, with Leon Fleisher as soloist and Leonard Bernstein conducting, and most recently on July 3, 1996, with Misha Dichter as soloist and Hermann Michael conducting. Liszt is music’s misunderstood genius. The greatest pianist of his time, he often has been caricatured as a mad, intemperate virtuoso and as a shameless and -

Highlighted = Needs to Be Written/Included

Seeing and Hearing Music COMBINING GENRES IN FILM VERSIONS OF BACH’S SIX SUITES FOR SOLO CELLO SENIOR THESIS FOR MUSIC SIMON LINN-GERSTEIN APRIL 20, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 LIST OF MUSIC EXAMPLES 3 LIST OF VIDEO CLIPS 4 INTRODUCING BACH SUITE FILMS 5 PART I: DIAGRAMMING MUSIC: MONTAGE AND SHOWING MUSICAL FORMS/GENRES 7 Introduction to Montage and Links to Sound Recording 7 Comparing Audio and Visual Methods 12 Montage Case Studies 14 PART II: GENERIC CROSSOVER: INFLUENCES FROM OTHER FILM TRADITIONS ON BACH SUITE MONTAGE 25 Documentary Film and Didactic Montage 25 Music Video: Illustrating Both Structure and Gesture 28 Case Studies: Comparing the Influence of Music Video on Two Bach Films 35 PART III: THE HISTORICAL BACH: REPRESENTING SOCIAL AND HISTORICAL CONTEXT/GENRES 41 Showing and Telling History 41 The Myth of Bach’s Spirituality: A History, and its Influence on Bach Suite Films 46 Cautious Avoidance of Historical Context 54 From Dances to DVDs: Melding New and Old Contexts and Genres 55 CONCLUSION 59 WORKS CITED/BIBLIOGRAPHY 61 2 MUSIC EXAMPLES 68 Example 1: Bach Well-Tempered Clavier, Fugue No. 20 in A minor, exposition Glenn Gould’s editing 68 Example 2: Bach Well-Tempered Clavier, Fugue No. 20 in A minor, conclusion Glenn Gould’s editing 69 Example 3: Bach Suites for Solo Cello, Suite No. 1 in G major, Allemande Pablo Casals and Wen-Sinn Yang’s editing 70 Example 4: Bach Suites for Solo Cello, Suite No. 3 in C major, Prelude Mstislav Rostropovich’s editing 71 Example 5: Bach Suites for Solo Cello, Suite No. -

Classical Programs

CLASSICAL PROGRAMS Traditional symphonic programs include Peter’s orchestral arrangements of Janacek’s Six Operatic Suites in his premiere recording for Naxos with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra; new arrangements of Mussorgsky’s Pictures from an Exhibition and Operatic Suites by Tchaikovsky to be released in fall/winter 2012 (also on Naxos) and featured in the movie documentary Bask ; new arrangements of Debussy’s Preludes to be released in September 2012; his arrangements of Brahms Hungarian Dances and works by Bizet, Granados, Albeniz, Handel, Schubert, Satie, Grieg and Tchaikovsky to name a few. Sample programs include… Dances from Around the World: A combination of original pieces and Breiner’s arrangements or the arrangements only. Program to be structured to suit audience and orchestra forces from the following works: - Arnold: English/Irish/Scottish/Cornish Dances - Bartok: Dances of Transsylvania /Rumanian Folk Dances - Borodin: Polovtsian Dances - Copland: Danzon Cubano - Dvorak: Slavonic Dances - Elgar: Three Bavarian Dances - Gorecki: Three Dances - Hindemith: Suite of French Dances - Janacek: Lachian Dances - Kodaly: Dances of Galanta / Marosszek - Mozart: German Dances - Skalkottas: Five Greek Dances - Smetana: Three Dances from Battered Bride - Villa-Lobos: Danses africaines / Danses des Indians For Audio samples please click here. …And Pictures: A program featuring Peter’s brand new and impressive arrangement of Mussorgsky’s warhorse – Pictures at an Exhibition in the second half, First half options: Etchings & Pictures …. Martinu: Estampes Haydn: Piano Concerto (conducted from piano) Stories & Pictures … Suk: Fairy Tale; or Stravinsky: Fairy’s Kiss; or Dvorak: Water Goblin/Golden Spinning Wheel/Midday Witch/ Mozart: Piano Concerto (conducted from piano) POPS PROGRAMS Programs can be structured to suit orchestra and audience from any era. -

Fall/Winter 2002/2003

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Fall/ Winter 2002 Bernstein's Mahler: A Personal View @ by Sedgwick Clark n idway through the Adagio £male of Mahler's Ninth M Symphony, the music sub sides from an almost desperate turbulence. Questioning wisps of melody wander throughout the woodwinds, accompanied by mut tering lower strings and a halting harp ostinato. Then, suddenly, the orchestra "vehemently burst[s] out" fortissimo in a final attempt at salvation. Most conductors impart a noble arch and beauty of tone to the music as it rises to its climax, which Leonard Bernstein did in his Vienna Philharmonic video recording in March 1971. But only seven months before, with the New York Philharmonic, His vision of the music is neither Nearly all of the Columbia cycle he had lunged toward the cellos comfortable nor predictable. (now on Sony Classical), taped with a growl and a violent stomp Throughout that live performance I between 1960 and 1974, and all of on the podium, and the orchestra had been struck by how much the 1980s cycle for Deutsche had responded with a ferocity I more searching and spontaneous it Grammophon, are handily gath had never heard before, or since, in was than his 1965 recording with ered in space-saving, budget-priced this work. I remember thinking, as the orchestra. Bernstein's Mahler sets. Some, but not all, of the indi Bernstein tightened the tempo was to take me by surprise in con vidual releases have survived the unmercifully, "Take it easy. Not so cert many times - though not deletion hammerschlag. -

Download Booklet

557757 bk Bloch US 20/8/07 8:50 pm Page 5 Royal Scottish National Orchestra the Sydney Opera, has been shown over fifty times on U.S. television, and has been released on DVD. Serebrier regularly champions contemporary music, having commissioned the String Quartet No. 4 by Elliot Carter (for his Formed in 1891 as the Scottish Orchestra, and subsequently known as the Scottish National Orchestra before being Festival Miami), and conducted world première performances of music by Rorem, Schuman, Ives, Knudsen, Biser, granted the title Royal at its centenary celebrations in 1991, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra is one of Europe’s and many others. As a composer, Serebrier has won most important awards in the United States, including two leading ensembles. Distinguished conductors who have contributed to the success of the orchestra include Sir John Guggenheims (as the youngest in that Foundation’s history, at the age of nineteen), Rockefeller Foundation grants, Barbirolli, Karl Rankl, Hans Swarowsky, Walter Susskind, Sir Alexander Gibson, Bryden Thomson, Neeme Järvi, commissions from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Harvard Musical Association, the B.M.I. Award, now Conductor Laureate, and Walter Weller who is now Conductor Emeritus. Alexander Lazarev, who served as Koussevitzky Foundation Award, among others. Born in Uruguay of Russian and Polish parents, Serebrier has Ernest Principal Conductor from 1997 to 2005, was recently appointed Conductor Emeritus. Stéphane Denève was composed more than a hundred works. His First Symphony had its première under Leopold Stokowski (who gave appointed Music Director in 2005 and his first recording with the RSNO of Albert Roussel’s Symphony No. -

2017–2018 Season Artist Index

2017–2018 Season Artist Index Following is an alphabetical list of artists and ensembles performing in Stern Auditorium / Perelman Stage (SA/PS), Zankel Hall (ZH), and Weill Recital Hall (WRH) during Carnegie Hall’s 2017–2018 season. Corresponding concert date(s) and concert titles are also included. For full program information, please refer to the 2017–2018 chronological listing of events. Adès, Thomas 10/15/2017 Thomas Adès and Friends (ZH) Aimard, Pierre-Laurent 3/8/2018 Pierre-Laurent Aimard (SA/PS) Alarm Will Sound 3/16/2018 Alarm Will Sound (ZH) Altstaedt, Nicolas 2/28/2018 Nicolas Altstaedt / Fazil Say (WRH) American Composers Orchestra 12/8/2017 American Composers Orchestra (ZH) 4/6/2018 American Composers Orchestra (ZH) Anderson, Laurie 2/8/2018 Nico Muhly and Friends Investigate the Glass Archive (ZH) Angeli, Paolo 1/26/2018 Paolo Angeli (ZH) Ansell, Steven 4/13/2018 Boston Symphony Orchestra (SA/PS) Apollon Musagète Quartet 2/16/2018 Apollon Musagète Quartet (WRH) Apollo’s Fire 3/22/2018 Apollo’s Fire (ZH) Arcángel 3/17/2018 Andalusian Voices: Carmen Linares, Marina Heredia, and Arcángel (SA/PS) Archibald, Jane 3/25/2018 The English Concert (SA/PS) Argerich, Martha 10/20/2017 Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia (SA/PS) 3/22/2018 Itzhak Perlman / Martha Argerich (SA/PS) Artemis Quartet 4/10/2018 Artemis Quartet (ZH) Atwood, Jim 2/27/2018 Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra (SA/PS) Ax, Emanuel 2/22/2018 Emanuel Ax / Leonidas Kavakos / Yo-Yo Ma (SA/PS) 5/10/2018 Emanuel Ax (SA/PS) Babayan, Sergei 3/1/2018 Daniil -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

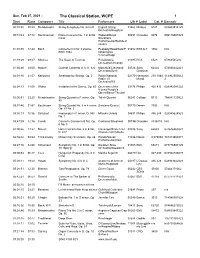

Sun, Feb 07, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 09:23 Mendelssohn String Symphony No. 02 in D English String 01460 Nimbus 5141 083603514129 Orchestra/Boughton 00:12:2347:12 Stenhammar Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat Widlund/Royal 00391 Chandos 9074 095115907429 minor Stockholm Philharmonic/Rozhdest vensky 01:01:0517:24 Bach Concerto in D for 3 Violins, Peabody/Rood/Sato/P 01652 ESS.A.Y 1002 N/A BWV 1064 hilharmonia Virtuosi/Kapp 01:19:2909:47 Sibelius The Swan of Tuonela Philadelphia 01095 RCA 6528 07863565282 Orchestra/Ormandy 01:30:4629:00 Mozart Clarinet Concerto in A, K. 622 Marcellus/Cleveland 03728 Sony 62424 074646242421 Orchestra/Szell Classical 02:01:1621:57 Karlowicz Serenade for Strings, Op. 2 Polish National 02170 Harmonia 278 1088 314902505612 Radio-TV Mundi 2 Orchestra/Wit 02:24:13 11:08 Weber Invitation to the Dance, Op. 65 Orchestra of the 03176 Philips 420 812 028942081222 Vienna People's Opera/Bauer-Theussl 02:36:5123:25 Mendelssohn String Quartet in F minor, Op. Talich Quartet 06241 Calliope 9313 794881725922 80 03:01:4631:57 Beethoven String Quartet No. 8 in E minor, Smetana Quartet 00270 Denon 7033 N/A Op. 59 No. 2 03:35:1310:56 Schubert Impromptu in F minor, D. 935 Mitsuko Uchida 04691 Philips 456 245 028945624525 No. 1 03:47:0912:16 Corelli Concerto Grosso in B flat, Op. Cantilena/Shepherd 00794B Chandos 8336/7/8 N/A 6 No. 5 04:00:5514:27 Mozart Horn Concerto No. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Thomas, Augusta Read Dancing Helix Rituals

Dancing Helix Rituals (2006) Augusta Read Thomas “Somewhat of a cross between ‘Jazz’ (Monk, Coltrain, Tatum, Miles, etc.) and ‘Classical’ (Bartok, Stravinsky, Varèse, Berio, Boulez, etc.), Dancing Helix Rituals can be heard as a lively dance made up of a series of outGrowths and variations which are orGanic and, at every level, concerned with transformations and connections. Each player serves as a protagonist as well as a fulcrum point on and around which all others’ musical force fields rotate, bloom, and proliferate. There is refined loGic to every nuance which stems from the sound, in context, on its own terms and the form is that of an eiGht-minute crescendo. AlthouGh Dancing Helix Rituals stands fully on its own as art music, it can be performed along with dancers. The early Stravinsky ballets are works I hold in Great reverence, have studied, love, and embrace as models in my inner ear. As a result, I tend to hear and feel all of my music, in particular my orchestral works, as music suitable for dance. As I compose, I sinG, dance, move, and conduct at my draftinG table. The process is visceral. My ears and mind are both analytical as well as intuitive and I ‘feel’ and ‘hear’ every note and rhythm and color clearly. (I hope you can sense that precision.) This is music composed with the whole ear and whole body, not a cerebral, overly analytical exercise in pushinG twelve-tone rows–or spectra–or rearranGed quotes of borrowed ethnic phrases around a computer screen, for instance! The sounds are varied, colorful, crosscut, unexpected, and yet hopefully sound inevitable in the way that a jazz improvisation sounds spontaneous and unpreventable.