A Guide to Fixed-Income Investing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mortgage-Backed Securities & Collateralized Mortgage Obligations

Mortgage-backed Securities & Collateralized Mortgage Obligations: Prudent CRA INVESTMENT Opportunities by Andrew Kelman,Director, National Business Development M Securities Sales and Trading Group, Freddie Mac Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) have Here is how MBSs work. Lenders because of their stronger guarantees, become a popular vehicle for finan- originate mortgages and provide better liquidity and more favorable cial institutions looking for investment groups of similar mortgage loans to capital treatment. Accordingly, this opportunities in their communities. organizations like Freddie Mac and article will focus on agency MBSs. CRA officers and bank investment of- Fannie Mae, which then securitize The agency MBS issuer or servicer ficers appreciate the return and safety them. Originators use the cash they collects monthly payments from that MBSs provide and they are widely receive to provide additional mort- homeowners and “passes through” the available compared to other qualified gages in their communities. The re- principal and interest to investors. investments. sulting MBSs carry a guarantee of Thus, these pools are known as mort- Mortgage securities play a crucial timely payment of principal and inter- gage pass-throughs or participation role in housing finance in the U.S., est to the investor and are further certificates (PCs). Most MBSs are making financing available to home backed by the mortgaged properties backed by 30-year fixed-rate mort- buyers at lower costs and ensuring that themselves. Ginnie Mae securities are gages, but they can also be backed by funds are available throughout the backed by the full faith and credit of shorter-term fixed-rate mortgages or country. The MBS market is enormous the U.S. -

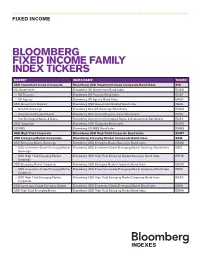

Bloomberg Fixed Income Family Index Tickers

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// FIXED INCOME BLOOMBERG FIXED INCOME FAMILY INDEX TICKERS MARKET INDEX NAME TICKER USD Investment Grade Composite Bloomberg USD Investment Grade Composite Bond Index BIG US Government Bloomberg US Government Bond Index BUSG » US Treasury Bloomberg US Treasury Bond Index BUSY » US Agency Bloomberg US Agency Bond Index BAGY USD Government Related Bloomberg USD Government Related Bond Index BGRL » Non-US Sovereign Bloomberg Non-US Sovereign Bond Index BNSO » Government Regional/Local Bloomberg Government Regional/Local Bond Index BRGL » Gov Developed Banks & Supra Bloomberg Government Developed Banks & Supranational Bond Index BDEV USD Corporate Bloomberg USD Corporate Bond Index BUSC US MBS Bloomberg US MBS Bond Index BMBS USD High Yield Corporate Bloomberg USD High Yield Corporate Bond Index BUHY USD Emerging Market Composite Bloomberg Emerging Market Composite Bond Index BEM USD Emerging Market Sovereign Bloomberg USD Emerging Market Sovereign Bond Index BEMS » USD Investment Grade Emerging Market Bloomberg USD Investment Grade Emerging Market Sovereign Bond Index BEIS Sovereign » USD High Yield Emerging Market Bloomberg USD High Yield Emerging Market Sovereign Bond Index BEHS Sovereign USD Emerging Market Corporate Bloomberg USD Emerging Market Corporate Bond Index BEMC » USD Investment Grade Emerging Market Bloomberg USD Investment Grade Emerging Market Corporate Bond Index BIEM Corporate -

Chapter 3 Fixed Income Securities

Chapter 3 Fixed Income Securities Road Map Part A Introduction to finance. Part B Valuation of assets, given discount rates. • Fixed-income securities. • Stocks. • Real assets (capital budgeting). Part C Determination of risk-adjusted discount rates. Part D Introduction to derivatives. Main Issues • Fixed-Income Markets • Term Structure of Interest Rates • Interest Rate Risk • Inflation Risk • Credit Risk Chapter 3 Fixed Income Securities 3-1 1 Fixed-Income Markets Definition: Fixed-income securities are financial claims with promised cash flows of fixed amount paid at fixed dates. Classification of Fixed-Income Securities: 1. Treasury Securities: • U.S. Treasury securities (bills, notes, bonds). • Bunds, JGBs, U.K. Gilts ... 2. Federal Agency Securities: • Securities issued by federal agencies (FHLB, FNMA ...). 3. Corporate Securities: • Commercial paper. • Medium-term notes (MTNs). • Corporate bonds ... 4. Municipal Securities. 5. Mortgage-Backed Securities. 6. ... Fall 2006 c J. Wang 15.401 Lecture Notes 3-2 Fixed Income Securities Chapter 3 Overview of Fixed-income Markets Composition of U.S. Debt Markets (2005) Market value % (in trillion dollars) Treasury 4.17 16.5 Corporate 4.99 19.7 Mortgage 5.92 23.4 Agency 2.60 10.3 Munies 2.23 8.8 Asset-Backed 1.96 7.7 Money Market 3.47 13.7 Total 25.33 Current Trends T. Corp. MBS Agency ABS Munies MM Total 1995 3.31 1.94 2.35 0.84 0.32 1.29 1.18 11.23 1996 3.44 2.12 2.49 0.93 0.40 1.30 1.39 12.01 1997 3.44 2.36 2.68 1.02 0.54 1.32 1.69 13.05 1998 3.34 2.71 2.96 1.30 0.73 1.40 1.98 14.42 1999 3.27 3.05 3.33 1.62 0.90 1.46 2.34 15.96 2000 2.95 3.36 3.56 1.85 1.07 1.48 2.66 16.95 2001 2.97 3.84 4.13 2.15 1.28 1.60 2.57 18.53 2002 3.20 4.09 4.70 2.29 1.54 1.73 2.55 20.15 2003 3.57 4.46 5.31 2.64 1.69 1.89 2.53 22.10 2004 3.94 3.70 5.47 2.75 1.83 2.02 2.87 23.58 2005 4.17 4.99 4.92 2.60 1.96 2.23 3.47 25.33 15.401 Lecture Notes c J. -

Managing Fixed Income Late in the Credit Cycle: Navigating the Path Forward

INCOME INVESTING Managing fixed income late in the credit cycle: navigating the path forward nuveen knows Highlights • While we are clearly in the late stage of the credit cycle, we don’t think a recession is imminent and believe investors should feel comfortable investing in credit 2Q19 markets throughout the rest of 2019. • We believe investors should focus on higher-quality issues with improving credit fundamentals, while seeking to diversify across industries and geographies. • Nuveen’s sector specialist teams are finding attractive opportunities in U.S. credit sectors, including high yield, but they are increasingly diversifying into other higher-income areas, such as emerging market debt and leveraged loans. • Active management can add value in any environment, but we believe it is especially beneficial at the current stage of the credit cycle. The multi-trillion-dollar question for investors: How late are we in the credit cycle, and what are the portfolio implications? That’s the question we most often hear from our clients. And while there are few certainties in life or markets, we feel confident in our answer: We are clearly in the late stage of the credit cycle. But “late” doesn’t mean “done,” and credit cycles don’t die of old age. Rather, a combination of fundamentals and sentiment bring about their demise, and even in their later stages, savvy investors can find opportunities not only to protect their investments, but to position their portfolios for an emphasis on income as the cycle turns. Nuveen believes most investors should be comfortable investing in the credit markets throughout the rest of 2019. -

Product Pitchbook

2Q 2021 Separately Managed Accounts WESTERN ASSET MUNICIPAL BOND LADDERS Separately Managed Accounts (SMAs) are investment services provided by Legg Mason Private Portfolio Group, LLC (LMPPG), a federally registered investment advisor. Client portfolios are managed based on investment instructions or advice provided by one or more of the following Franklin Templeton affiliated subadvisors: ClearBridge Investments, LLC. Management is implemented by LMPPG, the designated subadvisor or, in the case of certain programs, the program sponsor or its designee. These materials are being provided for illustrative and informational purposes only. The information contained herein is obtained from multiple sources that are believed to be reliable. However, such information has not been verified, and may be different from the information included in documents and materials created by the sponsor firm in whose investment program a client participates. Some sponsor firms may require that these materials be preceded or accompanied by investment profiles or other documents or materials prepared by such sponsor firms, which will be provided upon a client's request. For additional information, documents and/or materials, please speak to your financial professional or contact your sponsor firm. INVESTMENT PRODUCTS: NOT FDIC INSURED • NO BANK GUARANTEE • MAY LOSE VALUE Introduction | Franklin Templeton Franklin Templeton We aim to offer the best of both worlds: global strength and boutique specialization. Providing real customization backed by the scale and -

Morningstar Global Fixed Income Classification Methodology

? Morningstar Global Fixed Income Classification Morningstar Research Introduction Effective Oct. 31, 2016 Fixed-Income Sectors Contents The fixed-income securities and fixed-income derivative exposures within a portfolio are mapped into 1 Introduction Secondary Sectors that represent the most granular level of classification. Each item can also be 2 Super Sectors 10 Sectors grouped into one of several higher-level Primary Sectors, which ultimately roll up to five fixed-income Super Sectors. Important Disclosure The conduct of Morningstar’s analysts is governed Cash Sectors by Code of Ethics/Code of Conduct Policy, Personal Cash securities and cash-derivative exposures within a portfolio are mapped into Secondary Sectors that Security Trading Policy (or an equivalent of), and Investment Research Policy. For information represent the most granular level of classification. Each item can also be grouped into cash & regarding conflicts of interest, please visit: http://global.morningstar.com/equitydisclosures equivalents Primary Sector and into cash & equivalents Super Sector (cash & equivalents Primary Sector = cash & equivalents Super Sector ). Morningstar includes cash within fixed-income sectors. Cash is not a bond, but it is a type of fixed- income. When bond-fund managers are feeling nervous about interest rates rising, they might increase their cash stake to shorten the portfolio’s duration. Moving assets into cash is a defensive strategy for interest-rate risk. In addition, Morningstar includes securities that mature in less than 92 days in the definition of cash. The cash & equivalents Secondary Sectors allow for more-detailed identification of cash, allowing clients to see, for example, if the cash holdings are in currency or short-term government bonds. -

SIFMA Research Quarterly – 1Q21 US Fixed Income Markets – Issuance & Trading

Executive Summary SIFMA Research Quarterly – 1Q21 US Fixed Income Markets – Issuance & Trading April 2021 The SIFMA Research Quarterlies contain data and statistics on U.S. markets. The fixed income reports are split into two – (1) issuance and trading, (2) outstanding – given a delay in the reporting of outstanding data. The reports cover data on total U.S. fixed income markets, as captured in the SIFMA Research database: U.S. Treasuries, mortgage-backed securities, corporate bonds, municipal securities, federal agency securities, asset-backed securities, money markets (outstanding only), repurchase agreements (outstanding only) and secured overnight financing rate. All reports, including the equity quarterly, and corresponding databases can be found at: www.sifma.org/research US Fixed Income Markets – Issuance & Trading Page | 1 Executive Summary Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 US Fixed Income Markets vs. Rest of World .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Quarterly Performance ............................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Chart Book: Total Fixed Income ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Convertible Debentures – a Primer

Portfolio Advisory Group May 12, 2011 Convertible Debentures – A Primer A convertible debenture is a hybrid financial instrument Convertible debentures offer some advantages over that has both fixed income and equity characteristics. In investing in common equity. As holders of a more its simplest terms, it is a bond that gives the holder the senior security, investors have a greater claim on the option to convert into an underlying equity instrument at firm’s assets in the event of insolvency. Secondly, the a predetermined price. Thus, investors receive a regular investor’s income flow is more stable since coupon income flow through the coupon payments plus the payments are a contractual obligation. Finally, ability to participate in capital appreciation through the convertible bonds offer both a measure of protection potential conversion to equity. Convertible debentures in bear markets through the regular bond features and are usually subordinated to the company’s other debt. participation in capital appreciation in bull markets through the conversion option. Unlike traditional Convertible debentures are issued by companies as a bonds, convertible debentures trade on a stock means of deferred equity financing in the belief that exchange but generally have a small issue size which the present share price is too low for issuing common can result in limited liquidity. shares. These securities offer a conversion into the underlying issuer’s shares at prices above the current VALUATION level (referred to as the conversion premium). In A convertible bond can be thought of as a straight return for offering an equity option, firms realize both bond with a call option for the underlying equity interest savings, since coupons on convertible bonds security. -

The Debt Supercycle and How It Can Impact Fixed Income

A conversation with Paul Matlack The debt supercycle and how it can impact fixed income One important issue in the current fixed income environment is the debt supercycle, the rapidly growing assumption of debt by consumers, businesses, and governments. The fixed income investment team at Paul Matlack, CFA Delaware Investments — a group known for its frank and Senior Portfolio Manager, candid exchange of investment ideas and diversity of Fixed Income Strategist thought — has focused on the debt supercycle as just one of the key issues facing fixed income investors today. To gain perspective from a central member of the team, we spoke with senior portfolio manager Paul Matlack about the debt supercycle’s impact on the bond market. From your vantage point, what’s the situation with global debt levels? Without dispute, we have high debt levels in many major markets — the United States, Japan, and China among them. And there’s little doubt that those high debt levels are a headwind to growth. But overall, my view of the debt supercycle is that it’s akin to climate change: It’s definite, it’s real, and it’s a threat. While this is concerning, I’m not convinced that it necessarily poses a doomsday scenario. Rather, I look at how we can live with the debt supercycle and invest around it. Still, it’s hard for me to see how a problem of that magnitude gets solved short of reaching and sustaining strong growth rates — rates that will generate tax revenues and lead to debt being paid down. I recognize that a path for sustained, strong growth isn’t immediately clear, especially not in this environment where we’re assuming a U.S. -

Municipal Bond Investor Weekly September 20, 2021 Noreen Mcclure –Director, High Net Worth Drew O’Neil - VP, Fixed Income Strategist

Fixed Income Solutions Municipal Bond Investor Weekly September 20, 2021 Noreen McClure –Director, High Net Worth Drew O’Neil - VP, Fixed Income Strategist What To Do With MY Cash! Many investors are sitting on cash… a tremendous amount of cash. I recently read an article written by Ben Carlson, from his blog “A wealth of common sense” titled, “Why is There Nearly $10 Trillion Earning Nothing in Saving Accounts”? He mentioned that according to Bankrate the average interest rate for a savings account rate now is .06% or lower. So how much cash is sitting on the sidelines in your account? Don’t be paralyzed at these low rates, be proactive within the municipal market! Are you waiting for rates to rise? For over a decade we’ve talking about rising rates… but it hasn’t happened yet. In fact, the Fed has said they will not raise rates in the foreseeable future. Yet, many investors follow media pundits’ expectations, instead of doing what is right for their individual financial needs. Let’s review the fundamental principles of why we include individual municipal fixed income into our investment portfolios: wealth preservation, reliable tax efficient income, and a defined maturity date. These three attributes of an individual municipal bond are what highlights the overall attractiveness of the investment. I can understand your concerns about the future expectations of a rise in rates, however there are multiple strategies we can visit that could enhance your investment opportunities. I must note that none of these strategies provide guaranteed principal protected liquidity if an investor needs to liquidate prior to maturity; like a savings account would. -

Lord Abbett Bond Debenture Fund - Class a 06-30-21

Release Date Lord Abbett Bond Debenture Fund - Class A 06-30-21 .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Category Multisector Bond Investment Objective & Strategy Portfolio Analysis From the investment's prospectus Composition as of 05-31-21 % Assets Morningstar Fixed Income Style Box™ as of 05-31-21 The investment seeks high current income and the U.S. Stocks 9.7 High Avg Eff Duration 4.63 opportunity for capital appreciation to produce a high total Non-U.S. Stocks 0.8 Avg Eff Maturity 10.22 return. Bonds 88.3 Med Cash 0.0 To pursue its objective, under normal conditions, the Low fund invests at least 80% of its net assets, plus the amount Other 1.2 of any borrowings for investment purposes, in bonds, Ltd Mod Ext debentures and other fixed income securities. It may invest a substantial portion of its net assets in high-yield securities Top 10 Holdings as of 05-31-21 % Assets Morningstar F-I Sectors as of 05-31-21 % Fund (commonly referred to as "below investment grade" or "junk" Crowdstrike Holdings Inc 3% 02-15-29 0.50 ⁄ Government 3.28 bonds). The fund may invest up to 20% of its net assets in Tesla Inc 5.3% 08-15-25 0.48 › Corporate 81.09 equity securities, including common stocks, preferred stocks, Sprint Capital Corporation 6.88% 11-15-28 0.46 € Securitized 12.31 convertible preferred stocks, and similar instruments. Shake Shack Inc A 0.45 ‹ Municipal 3.22 Roblox Corp Ordinary Shares - Class A 0.43 Cash/Cash Equivalents 0.00 ....................................................................................................... fi Volatility and Risk PDC Energy Inc 0.42 ± Other 0.10 Volatility as of 06-30-21 HCA Inc. -

Private Debt in an Institutional Portfolio

Private Debt in an Institutional Portfolio Sanjay Mistry Background other payments) and the return of the original Mercer Private Markets principal at a defined point in the future. Over the last few years, institutional investors The debt is typically secured and has various have been increasing allocations to return- Tobias Ripka protections/covenants in place. The debt is seeking fixed income strategies and illiquid Mercer Private Markets also not widely held, and is customised to alternative assets. In doing so, the level of the borrower’s requirements, thus rendering portfolio sophistication within both allocations it illiquid. We note Private debt strategies has also been increasing and roles within the investments have existed for a number of portfolio get more explicitly defined. Some years, but were for a long time the preserve of a investors are looking for higher yield, some minority of investors of whom banks were the for more diversification and some taking most significant. Today, private debt is an asset opportunistic positions resulting from market class increasingly considered by a broad range dislocations. Consistent with this development, of institutional investors. one of the investment opportunities that Mercer has highlighted over the years has Although we see private debt as, first and been private debt; as an asset class that we foremost, a return opportunity, a degree of believe is attractive on risk-adjusted grounds, diversification with more traditional credit which can play different roles in the portfolio exposures can also be expected. Private debt context and directly plays into the financing encompasses corporate debt, real estate debt void which has arisen post the global financial and infrastructure debt, as well as some crisis.