A Framework to Guide Serious Computer Game Use in the Classroom Erica Southgate University of Newcastle, Australia, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

Handheld Microscope Users Guide

Handheld Microscope Users Guide www.ScopeCurriculum.com ii Handheld Microscope Users Guide Hand-Held Microscope User’s Guide Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................1 What is a Scope-On-A-Rope? .....................................................................................................1 Which model do you have?.........................................................................................................2 Analog vs. Digital .........................................................................................................................3 Where can I buy a SOAR? ...........................................................................................................3 NEW SCOPE-ON-A-ROPE..................................................................................................................4 Parts and Assembly of SOAR .....................................................................................................4 Connections .................................................................................................................................5 Turning It On.................................................................................................................................5 Comparing and Installing Lenses...............................................................................................6 How to Use and Capture Images with the 30X Lens.................................................................7 -

Fallout 3 Pc Download Meaga Fallout 3 Full Pc Game + Crack Cpy CODEX Torrent Free 2021

fallout 3 pc download meaga Fallout 3 Full Pc Game + Crack Cpy CODEX Torrent Free 2021. Fallout 3 Crack Game Gameplay New Vegas is a game from 2021. It is considered the most popular game since its launch. With it, you can create your own character of your choice and immerse yourself in a post-apocalyptic and inspiring world. In this game, every minute you will experience a war and you need to survive. Also, the game starts from here; The Wanderer is tasked with arresting a character who was trying to escape from James. Fallout 3 Crack Game Cpy: The latest version of Fallout 4 turned out to be obvious that the computer game is extremely famous and it just blew up all the racks. Additionally, it includes a player character known as Lonely Wanderer, who is a little boy. The fallout shelter is located in Washington, DC. The vault was sealed for 200 years until the player’s father, James, opened the door and disappeared without any information. The surrender took place on November 10, 2015 and, as shown by various information and realities, surveys of players and experts, a measure of fanart and conversations. Alternatively, you can also try Ashampoo Winoptimizer. Fallout 3 Crack Game Cpy: Download Fallout 3 Crack Ps4 was first released on October 25, 2008 in the United States. Also, it is available on Xbox 360, PC, PS4, Ps3, and other gaming stations. Similarly, the game features realistic first- or third-person combat. The game is planned for the retro-futuristic United States between the People’s Republic of China and America. -

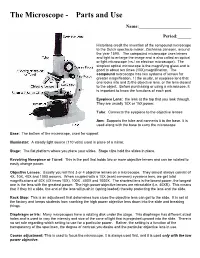

The Microscope Parts And

The Microscope Parts and Use Name:_______________________ Period:______ Historians credit the invention of the compound microscope to the Dutch spectacle maker, Zacharias Janssen, around the year 1590. The compound microscope uses lenses and light to enlarge the image and is also called an optical or light microscope (vs./ an electron microscope). The simplest optical microscope is the magnifying glass and is good to about ten times (10X) magnification. The compound microscope has two systems of lenses for greater magnification, 1) the ocular, or eyepiece lens that one looks into and 2) the objective lens, or the lens closest to the object. Before purchasing or using a microscope, it is important to know the functions of each part. Eyepiece Lens: the lens at the top that you look through. They are usually 10X or 15X power. Tube: Connects the eyepiece to the objective lenses Arm: Supports the tube and connects it to the base. It is used along with the base to carry the microscope Base: The bottom of the microscope, used for support Illuminator: A steady light source (110 volts) used in place of a mirror. Stage: The flat platform where you place your slides. Stage clips hold the slides in place. Revolving Nosepiece or Turret: This is the part that holds two or more objective lenses and can be rotated to easily change power. Objective Lenses: Usually you will find 3 or 4 objective lenses on a microscope. They almost always consist of 4X, 10X, 40X and 100X powers. When coupled with a 10X (most common) eyepiece lens, we get total magnifications of 40X (4X times 10X), 100X , 400X and 1000X. -

Chapter 11 Applications of Ore Microscopy in Mineral Technology

CHAPTER 11 APPLICATIONS OF ORE MICROSCOPY IN MINERAL TECHNOLOGY 11.1 INTRODUCTION The extraction of specific valuable minerals from their naturally occurring ores is variously termed "ore dressing," "mineral dressing," and "mineral beneficiation." For most metalliferous ores produced by mining operations, this extraction process is an important intermediatestep in the transformation of natural ore to pure metal. Although a few mined ores contain sufficient metal concentrations to require no beneficiation (e.g., some iron ores), most contain relatively small amounts of the valuable metal, from perhaps a few percent in the case ofbase metals to a few parts per million in the case ofpre cious metals. As Chapters 7, 9, and 10ofthis book have amply illustrated, the minerals containing valuable metals are commonly intergrown with eco nomically unimportant (gangue) minerals on a microscopic scale. It is important to note that the grain size of the ore and associated gangue minerals can also have a dramatic, and sometimes even limiting, effect on ore beneficiation. Figure 11.1 illustrates two rich base-metal ores, only one of which (11.1b) has been profitably extracted and processed. The McArthur River Deposit (Figure I 1.1 a) is large (>200 million tons) and rich (>9% Zn), but it contains much ore that is so fine grained that conventional processing cannot effectively separate the ore and gangue minerals. Consequently, the deposit remains unmined until some other technology is available that would make processing profitable. In contrast, the Ruttan Mine sample (Fig. 11.1 b), which has undergone metamorphism, is relativelycoarsegrained and is easily and economically separated into high-quality concentrates. -

Science for Energy Technology: Strengthening the Link Between Basic Research and Industry

ďŽƵƚƚŚĞĞƉĂƌƚŵĞŶƚŽĨŶĞƌŐLJ͛ƐĂƐŝĐŶĞƌŐLJ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞƐWƌŽŐƌĂŵ ĂƐŝĐŶĞƌŐLJ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞƐ;^ͿƐƵƉƉŽƌƚƐĨƵŶĚĂŵĞŶƚĂůƌĞƐĞĂƌĐŚƚŽƵŶĚĞƌƐƚĂŶĚ͕ƉƌĞĚŝĐƚ͕ĂŶĚƵůƟŵĂƚĞůLJĐŽŶƚƌŽů ŵĂƩĞƌĂŶĚĞŶĞƌŐLJĂƚƚŚĞĞůĞĐƚƌŽŶŝĐ͕ĂƚŽŵŝĐ͕ĂŶĚŵŽůĞĐƵůĂƌůĞǀĞůƐ͘dŚŝƐƌĞƐĞĂƌĐŚƉƌŽǀŝĚĞƐƚŚĞĨŽƵŶĚĂƟŽŶƐ ĨŽƌŶĞǁĞŶĞƌŐLJƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐŝĞƐĂŶĚƐƵƉƉŽƌƚƐKŵŝƐƐŝŽŶƐŝŶĞŶĞƌŐLJ͕ĞŶǀŝƌŽŶŵĞŶƚ͕ĂŶĚŶĂƟŽŶĂůƐĞĐƵƌŝƚLJ͘dŚĞ ^ƉƌŽŐƌĂŵĂůƐŽƉůĂŶƐ͕ĐŽŶƐƚƌƵĐƚƐ͕ĂŶĚŽƉĞƌĂƚĞƐŵĂũŽƌƐĐŝĞŶƟĮĐƵƐĞƌĨĂĐŝůŝƟĞƐƚŽƐĞƌǀĞƌĞƐĞĂƌĐŚĞƌƐĨƌŽŵ ƵŶŝǀĞƌƐŝƟĞƐ͕ŶĂƟŽŶĂůůĂďŽƌĂƚŽƌŝĞƐ͕ĂŶĚƉƌŝǀĂƚĞŝŶƐƟƚƵƟŽŶƐ͘ ďŽƵƚƚŚĞ͞ĂƐŝĐZĞƐĞĂƌĐŚEĞĞĚƐ͟ZĞƉŽƌƚ^ĞƌŝĞƐ KǀĞƌƚŚĞƉĂƐƚĞŝŐŚƚLJĞĂƌƐ͕ƚŚĞĂƐŝĐŶĞƌŐLJ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞƐĚǀŝƐŽƌLJŽŵŵŝƩĞĞ;^ͿĂŶĚ^ŚĂǀĞĞŶŐĂŐĞĚ ƚŚŽƵƐĂŶĚƐŽĨƐĐŝĞŶƟƐƚƐĨƌŽŵĂĐĂĚĞŵŝĂ͕ŶĂƟŽŶĂůůĂďŽƌĂƚŽƌŝĞƐ͕ĂŶĚŝŶĚƵƐƚƌLJĨƌŽŵĂƌŽƵŶĚƚŚĞǁŽƌůĚƚŽƐƚƵĚLJ ƚŚĞĐƵƌƌĞŶƚƐƚĂƚƵƐ͕ůŝŵŝƟŶŐĨĂĐƚŽƌƐ͕ĂŶĚƐƉĞĐŝĮĐĨƵŶĚĂŵĞŶƚĂůƐĐŝĞŶƟĮĐďŽƩůĞŶĞĐŬƐďůŽĐŬŝŶŐƚŚĞǁŝĚĞƐƉƌĞĂĚ ŝŵƉůĞŵĞŶƚĂƟŽŶŽĨĂůƚĞƌŶĂƚĞĞŶĞƌŐLJƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐŝĞƐ͘dŚĞƌĞƉŽƌƚƐĨƌŽŵƚŚĞĨŽƵŶĚĂƟŽŶĂůĂƐŝĐZĞƐĞĂƌĐŚEĞĞĚƐƚŽ ƐƐƵƌĞĂ^ĞĐƵƌĞŶĞƌŐLJ&ƵƚƵƌĞǁŽƌŬƐŚŽƉ͕ƚŚĞĨŽůůŽǁŝŶŐƚĞŶ͞ĂƐŝĐZĞƐĞĂƌĐŚEĞĞĚƐ͟ǁŽƌŬƐŚŽƉƐ͕ƚŚĞƉĂŶĞůŽŶ 'ƌĂŶĚŚĂůůĞŶŐĞƐĐŝĞŶĐĞ͕ĂŶĚƚŚĞƐƵŵŵĂƌLJƌĞƉŽƌƚEĞǁ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞĨŽƌĂ^ĞĐƵƌĞĂŶĚ^ƵƐƚĂŝŶĂďůĞŶĞƌŐLJ&ƵƚƵƌĞ ĚĞƚĂŝůƚŚĞŬĞLJďĂƐŝĐƌĞƐĞĂƌĐŚŶĞĞĚĞĚƚŽĐƌĞĂƚĞƐƵƐƚĂŝŶĂďůĞ͕ůŽǁĐĂƌďŽŶĞŶĞƌŐLJƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐŝĞƐŽĨƚŚĞĨƵƚƵƌĞ͘dŚĞƐĞ ƌĞƉŽƌƚƐŚĂǀĞďĞĐŽŵĞƐƚĂŶĚĂƌĚƌĞĨĞƌĞŶĐĞƐŝŶƚŚĞƐĐŝĞŶƟĮĐĐŽŵŵƵŶŝƚLJĂŶĚŚĂǀĞŚĞůƉĞĚƐŚĂƉĞƚŚĞƐƚƌĂƚĞŐŝĐ ĚŝƌĞĐƟŽŶƐŽĨƚŚĞ^ͲĨƵŶĚĞĚƉƌŽŐƌĂŵƐ͘;ŚƩƉ͗ͬͬǁǁǁ͘ƐĐ͘ĚŽĞ͘ŐŽǀͬďĞƐͬƌĞƉŽƌƚƐͬůŝƐƚ͘ŚƚŵůͿ ϭ ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞĨŽƌŶĞƌŐLJdĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐLJ͗^ƚƌĞŶŐƚŚĞŶŝŶŐƚŚĞ>ŝŶŬďĞƚǁĞĞŶĂƐŝĐZĞƐĞĂƌĐŚĂŶĚ/ŶĚƵƐƚƌLJ Ϯ EĞǁ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞĨŽƌĂ^ĞĐƵƌĞĂŶĚ^ƵƐƚĂŝŶĂďůĞŶĞƌŐLJ&ƵƚƵƌĞ ϯ ŝƌĞĐƟŶŐDĂƩĞƌĂŶĚŶĞƌŐLJ͗&ŝǀĞŚĂůůĞŶŐĞƐĨŽƌ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞĂŶĚƚŚĞ/ŵĂŐŝŶĂƟŽŶ ϰ ĂƐŝĐZĞƐĞĂƌĐŚEĞĞĚƐĨŽƌDĂƚĞƌŝĂůƐƵŶĚĞƌdžƚƌĞŵĞŶǀŝƌŽŶŵĞŶƚƐ ϱ ĂƐŝĐZĞƐĞĂƌĐŚEĞĞĚƐ͗ĂƚĂůLJƐŝƐĨŽƌŶĞƌŐLJ -

Microscope Innovation Issue Fall 2020

Masks • COVID-19 Testing • PAPR Fall 2020 CHIhealth.com The Innovation Issue “Armor” invention protects test providers 3D printing boosts PPE supplies CHI Health Physician Journal WHAT’S INSIDE Vol. 4, Issue 1 – Fall 2020 microscope is a journal published by CHI Health Marketing and Communications. Content from the journal may be found at CHIhealth.com/microscope. SUPPORTING COMMUNITIES Marketing and Communications Tina Ames Division Vice President Making High-Quality Masks 2 for the Masses Public Relations Mary Williams CHI Health took a proactive approach to protecting the community by Division Director creating and handing out thousands of reusable facemasks which were tested to ensure they were just as effective after being washed. Editorial Team Sonja Carberry Editor TACKLING CHALLENGES Julie Lingbloom Graphic Designer 3D Printing Team Helps Keep Taylor Barth Writer/Associate Editor 4 PAPRs in Use Jami Crawford Writer/Associate Editor When parts of Powered Air Purifying Respirators (PAPRS) were breaking, Anissa Paitz and reordering proved nearly impossible, a team of creators stepped in with a Writer/Associate Editor workable prototype that could be easily produced. Photography SHARING RESOURCES Andrew Jackson Grassroots Effort Helps Shield 6 Nebraska from COVID-19 About CHI Health When community group PPE for NE decided to make face shields for health care providers, CHI Health supplied 12,000 PVC sheets for shields and CHI Health is a regional health network headquartered in Omaha, Nebraska. The 119 kg of filament to support their efforts. combined organization consists of 14 hospitals, two stand-alone behavioral health facilities, more than 150 employed physician ADVANCING CAPABILITIES practice locations and more than 12,000 employees in Nebraska and southwestern Iowa. -

Global Microscope 2015 the Enabling Environment for Financial Inclusion

An index and study by The Economist Intelligence Unit GLOBAL MICROSCOPE 2015 THE enabling ENVIRONMENT FOR financial inclusiON Supported by Global Microscope 2015 The enabling environment for financial inclusion About this report The Global Microscope 2015: The enabling environment for financial inclusion, formerly known as the Global Microscope on the Microfinance Business Environment, assesses the regulatory environment for financial inclusion across 12 indicators and 55 countries. The Microscope was originally developed for countries in the Latin America and Caribbean region in 2007 and was expanded into a global study in 2009. Most of the research for this report, which included interviews and desk analysis, was conducted between June and September 2015. This work was supported by funding from the Multilateral Investment Fund (MIF), a member of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) Group; CAF—Development Bank of Latin America; the Center for Financial Inclusion at Accion, and the MetLIfe Foundation. The complete index, as well as detailed country analysis, can be viewed on these websites: www.eiu.com/microscope2015; www.fomin.org; www.caf.com/en/msme; www.centerforfinancialinclusion.org/microscope; www.metlife.org Please use the following when citing this report: The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). 2015. Global Microscope 2015: The enabling environment for financial inclusion. Sponsored by MIF/IDB, CAF, Accion and the Metlife Foundation. EIU, New York, NY. For further information, please contact: [email protected] 1 © The Economist -

Scanning Tunneling Microscope Control System for Atomically

Innovations in Scanning Tunneling Microscope Control Systems for This project will develop a microelectromechanical system (MEMS) platform technology for scanning probe microscope-based, high-speed atomic scale High-throughput fabrication. Initially, it will be used to speed up, by more than 1000 times, today’s Atomically Precise single tip hydrogen depassivation lithography (HDL), enabling commercial fabrication of 2D atomically precise nanoscale devices. Ultimately, it could be used to fabricate Manufacturing 3D atomically precise materials, features, and devices. Graphic image courtesy of University of Texas at Dallas and Zyvex Labs Atomically precise manufacturing (APM) is an emerging disruptive technology precision movement in three dimensions mechanosynthesis (i.e., moving single that could dramatically reduce energy are also needed for the required accuracy atoms mechanically to control chemical and coordination between the multiple reactions) of three dimensional (3D) use and increase performance of STM tips. By dramatically improving the devices and for subsequent positional materials, structures, devices, and geometry and control of STMs, they can assembly of nanoscale building blocks. finished goods. Using APM, every atom become a platform technology for APM and deliver atomic-level control. First, is at its specified location relative Benefits for Our Industry and an array of micro-machined STMs that Our Nation to the other atoms—there are no can work in parallel for high-speed and defects, missing atoms, extra atoms, high-throughput imaging and positional This APM platform technology will accelerate the development of tools and or incorrect (impurity) atoms. Like other assembly will be designed and built. The system will utilize feedback-controlled processes for manufacturing materials disruptive technologies, APM will first microelectromechanical system (MEMS) and products that offer new functional be commercialized in early premium functioning as independent STMs that can qualities and ultra-high performance. -

The-Pathologists-Microscope.Pdf

The Pathologist’s Microscope The Pathologist’s Microscope Rudolf Virchow, the father of Pathology, had available to him wonderful microscopes during the 1850’s to 1880’s, but the one you have now is far better. Your microscope is the most highly perfected of all scientific instruments. These brief notes on alignment, the objective lens, the condenser, and the eyepieces are what you need to know to get the most out of your microscope and to feel comfortable using it. Figure 1 illustrates the important parts of a generic modern light microscope. Figure 1 - Parts of the Microscope UNC Pathology & Lab Med, MSL, July 2013 1 The Pathologist’s Microscope Alignment August Köhler, in 1870, invented the method for aligning the microscope’s optical system that is still used in all modern microscopes. To get the most from your microscope it should be Köhler aligned. Here is how: 1. Focus a specimen slide at 10X. 2. Open the field iris and the condenser iris. 3. Observe the specimen and close the field iris until its shadow appears on the specimen. 4. Use the condenser focus knob to bring the field iris into focus on the specimen. Try for as sharp an image of the iris as you can get. If you can’t focus the field iris, check the condenser for a flip-in lens and find the configuration that lets you see the field iris. You may also have to move the field iris into the field of view (step 5) if it is grossly misaligned. 5.Center the field iris with the condenser centering screws. -

The Annual Compendium of Commercial Space Transportation: 2017

Federal Aviation Administration The Annual Compendium of Commercial Space Transportation: 2017 January 2017 Annual Compendium of Commercial Space Transportation: 2017 i Contents About the FAA Office of Commercial Space Transportation The Federal Aviation Administration’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation (FAA AST) licenses and regulates U.S. commercial space launch and reentry activity, as well as the operation of non-federal launch and reentry sites, as authorized by Executive Order 12465 and Title 51 United States Code, Subtitle V, Chapter 509 (formerly the Commercial Space Launch Act). FAA AST’s mission is to ensure public health and safety and the safety of property while protecting the national security and foreign policy interests of the United States during commercial launch and reentry operations. In addition, FAA AST is directed to encourage, facilitate, and promote commercial space launches and reentries. Additional information concerning commercial space transportation can be found on FAA AST’s website: http://www.faa.gov/go/ast Cover art: Phil Smith, The Tauri Group (2017) Publication produced for FAA AST by The Tauri Group under contract. NOTICE Use of trade names or names of manufacturers in this document does not constitute an official endorsement of such products or manufacturers, either expressed or implied, by the Federal Aviation Administration. ii Annual Compendium of Commercial Space Transportation: 2017 GENERAL CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Introduction 5 Launch Vehicles 9 Launch and Reentry Sites 21 Payloads 35 2016 Launch Events 39 2017 Annual Commercial Space Transportation Forecast 45 Space Transportation Law and Policy 83 Appendices 89 Orbital Launch Vehicle Fact Sheets 100 iii Contents DETAILED CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . -

Development of the Optical Microscope

White Paper Development of the Optical Microscope By Peter Banks Ph.D., Scientific Director, Applications Dept., BioTek Instruments, Inc. Products: Cytation 5 Cell Imaging Multi-Mode Reader An Optical Microscope commonly found in schools and universities all over the world. Table of Contents Ptolemy and Light Refraction --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Islamic Polymaths and Optics -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 The First Microscope ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Hook and Micrographia --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Van Leeuwenhoek and Animalcules ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 5 Abbe Limit -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Zernicke and Phase Contrast --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Fluorescence Microscopy ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Confocal Microscopy ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 BioTek Instruments, Inc. Digital Microscopy ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------