Episodes of Improvisational Lyricism from Hiphop to Pragmatism By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brink, D.H. Van Den 1.Pdf

Daan van den Brink s4369106 16 Aug. 2018 MA Creative Industries Rap Record for Sale - Sampling practice and commodification in Madlib Invazion. Cover image: Trouble Knows Me, Trouble Knows Me. Los Angeles: Madlib Invazion. (MMS-027), 2015. Daan van den Brink (s4369106) Email: [email protected] Rap Record for Sale – Sampling practice and commodification in Madlib Invazion. MA Thesis Creative Industries. Date of submission: 6 Aug. 2018 Supervisor: dr. Vincent Meelberg Email: [email protected] Abstract. Within our capitalistic society, much if not all the music we consume is to be regarded as commodities. Musical products are subject to numerous processes, rules and regulations, one of which being copyright. Essentially, copyright enables the musical product as commodity, and as David Hesmondhalgh puts it, has become the main means of commodifying culture. A musical practice that is particularly at odds with copyright is sampling, which makes use of previously recorded material through recombination and re-contextualisation. For the use of samples, a proper copyright license must be in place, whether the sample-based song is being monetized on or released for free. However, hip hop producers often do not comply in licensing the use of copyrighted material in their music, which challenges not only the copyright regime, but also copyright as a means of commodification. Over the years, copyright has become an extensive set of rights, resulting in the criminalization of unlicensed use of samples, but not in prevention, as technological advancements have made sampling a more widespread and accessible practice. Within this thesis, the sample-based work of Madlib as released on his Madlib Invazion label is used as a case study to map the current copyright regime, the costs of licensing and the risks of unlicensed sampling. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/65f2825x Author Young, Mark Thomas Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Thomas Young June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Steven Gould Axelrod Dr. Tom Lutz Copyright by Mark Thomas Young 2015 The Dissertation of Mark Thomas Young is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As there are many midwives to an “individual” success, I’d like to thank the various mentors, colleagues, organizations, friends, and family members who have supported me through the stages of conception, drafting, revision, and completion of this project. Perhaps the most important influences on my early thinking about this topic came from Paweł Frelik and Larry McCaffery, with whom I shared a rousing desert hike in the foothills of Borrego Springs. After an evening of food, drink, and lively exchange, I had the long-overdue epiphany to channel my training in musical performance more directly into my academic pursuits. The early support, friendship, and collegiality of these two had a tremendously positive effect on the arc of my scholarship; knowing they believed in the project helped me pencil its first sketchy contours—and ultimately see it through to the end. -

Funkin-For-Jamaica (Wax Poetics)

“Invaluable” —Jazz Times Coltrane year, fusing rap and rock together on Run-DMC’s “Rock Box” “Tom Browne, he’s just an ordinary guy.” What he’s saying (with the aid of Don Blackman/Lenny White sideman Eddie is, “This isn’t even his music; what’s he doing here?” It was on Martinez on the track’s blazing guitar lead.) He wasn’t the kind of derogatory, and that feeling permeated through a lot Coltrane only one of the Kats to move behind the scenes as hip-hop of the Kats. exploded around them: Denzil Miller arranged Kurtis Blow’s Wright: [’Nard] sold 200,000 copies without any promotion. The “Christmas Rappin’ ”; Don Blackman played the piano lead But [GRP] told me it wasn’t marketable, because they needed John Coltrane on the Fat Boys’ classic “Jail House Rap”; Bernard Wright a bin for it in the record store. You can’t have a record with worked on Doug E. Fresh and the Get Fresh Crew’s Oh, My traditional jazz and funk and R&B on the same album, they Interviews God! album. were saying. But that’s what Jamaica, Queens, was. As hip-hop exploded, the next generation of would-be Miller: Right after Tom and Bernard did their albums, I Edited by Kats laid down their instruments and picked up mics. Mean- talked to Dr. George Butler, who was the head of jazz at Chris DeVito while, the arrival of crack and the presence of violent kingpins Columbia, and said, “I’m thinking about doing my own al- like Lorenzo “Fat Cat” Nichols tainted the area’s safe, middle- bum. -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

The Role of Radicalism in African-American Protest Music

“WE’D RATHER DIE ON OUR FEET THAN BE LIVIN’ ON OUR KNEES” THE ROLE OF RADICALISM IN AFRICAN-AMERICAN PROTEST MUSIC, 1960 – 1990: A CASE STUDY AND LYRICAL ANALYSIS Master’s Thesis in North American Studies Leiden University By Roos Fransen 1747045 10 June 2018 Supervisor: Dr. S.A. Polak Second reader: Dr. M.L. de Vries Contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1: Nina Simone and calling out racism 12 Chapter 2: James Brown, black emancipation and self-pride 27 Chapter 3: Public Enemy, black militancy and distrust of government and 40 media Conclusion 52 Works cited 56 2 Introduction The social importance of African-American music originates in the arrival of African slaves on the North American continent. The captured Africans transported to the British colonial area that would later become the United States came from a variety of ethnic groups with a long history of distinct and cultivated musical traditions. New musical forms came into existence, influenced by Christianity, yet strongly maintaining African cultural traditions. One of the most widespread early musical forms among enslaved Africans was the spiritual. Combining Christian hymns and African rhythms, spirituals became a distinctly African- American response to conditions on the plantations slaves were forced to work1. They expressed the slaves’ longing for spiritual and physical freedom, for safety from harm and evil, and for relief from the hardships of slavery. Many enslaved people were touched by the metaphorical language of the Bible, identifying for example with the oppressed Israelites of the Old Testament, as this spiritual Go Down Moses illustrates: Go down, Moses Way down in Egypt's land Tell old Pharaoh Let my people go2 The spiritual is inspired by Exodus 8:1, a verse in the Old Testament. -

To Access the Inkling Language Guide!

- 1 - The following guide is a collection of phonetics, vocabulary and grammar points assembled by Splatoon players for a fan-made Inkling constructed language (or conlang). This language is not meant to serve as a guide to any in-game dialogue, lyrics, or written text. This is a fan project. This was undertaken out of love and respect for Nintendo and their fantastic and imaginative third-person shooter. We hope that all Splatoon fans worldwide can understand our very simple conlang and use this for their own creative fun projects from comics to posters to apparel to whatever their minds can cook up. The language nerds of Squidboards extend to everyone a hearty and fresh welcome to our Inkling conlang! Looking for a particular word? Ctrl + F and type it in! Otherwise, we have organized all of our content into manageable units and lessons for easy consumption and optimal relevance. There are eight Units, each containing two Lessons. Each Lesson teaches one set of Vocabulary and one bit of Grammar. At the end, there are more sections with supplementary material. Find a mistake? Did I make a typo somewhere? If there’s some sort of error in this guide that you find, please notify me (Piyoz) immediately so I can iron that out. You can contact me through the email form on the website where you downloaded this guide. Thanks to the following contributors for all their hard work: JosephStaleKnight (for creating all the vector images that made this guide possible), EclipseMT (for suggesting random ideas that usually made their way here), the Fizzynator -

The History and Development of Jazz Piano : a New Perspective for Educators

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1975 The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators. Billy Taylor University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Taylor, Billy, "The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators." (1975). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 3017. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/3017 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. / DATE DUE .1111 i UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS LIBRARY LD 3234 ^/'267 1975 T247 THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented By William E. Taylor Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfil Iment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF EDUCATION August 1975 Education in the Arts and Humanities (c) wnii aJ' THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO: A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation By William E. Taylor Approved as to style and content by: Dr. Mary H. Beaven, Chairperson of Committee Dr, Frederick Till is. Member Dr. Roland Wiggins, Member Dr. Louis Fischer, Acting Dean School of Education August 1975 . ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO; A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS (AUGUST 1975) William E. Taylor, B.S. Virginia State College Directed by: Dr. -

Fallout 3 Pc Download Meaga Fallout 3 Full Pc Game + Crack Cpy CODEX Torrent Free 2021

fallout 3 pc download meaga Fallout 3 Full Pc Game + Crack Cpy CODEX Torrent Free 2021. Fallout 3 Crack Game Gameplay New Vegas is a game from 2021. It is considered the most popular game since its launch. With it, you can create your own character of your choice and immerse yourself in a post-apocalyptic and inspiring world. In this game, every minute you will experience a war and you need to survive. Also, the game starts from here; The Wanderer is tasked with arresting a character who was trying to escape from James. Fallout 3 Crack Game Cpy: The latest version of Fallout 4 turned out to be obvious that the computer game is extremely famous and it just blew up all the racks. Additionally, it includes a player character known as Lonely Wanderer, who is a little boy. The fallout shelter is located in Washington, DC. The vault was sealed for 200 years until the player’s father, James, opened the door and disappeared without any information. The surrender took place on November 10, 2015 and, as shown by various information and realities, surveys of players and experts, a measure of fanart and conversations. Alternatively, you can also try Ashampoo Winoptimizer. Fallout 3 Crack Game Cpy: Download Fallout 3 Crack Ps4 was first released on October 25, 2008 in the United States. Also, it is available on Xbox 360, PC, PS4, Ps3, and other gaming stations. Similarly, the game features realistic first- or third-person combat. The game is planned for the retro-futuristic United States between the People’s Republic of China and America. -

Janus: the Monstrosity of Genre

Janus: the Monstrosity of Genre by Gianni Washington ! Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Creative Writing University of Surrey Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences School of Literature and Languages Supervisors: Dr. Paul Vlitos & Dr. Allan Johnson © Gianni Washington 2018 !1 Declaration This thesis and the work to which it refers are the results of my own efforts. Any ideas, data, images or text resulting from the work of others (whether published or unpublished) are fully identified as such within the work and attributed to their originator in the text, bibliography or in footnotes. This thesis has not been submitted in whole or in part for any other academic degree or professional qualification. I agree that the University has the right to submit my work to the plagiarism detection service TurnitinUK for originality checks. Whether or not drafts have been so-assessed, the University reserves the right to require an electronic version of the final document (as submitted) for assessment as above. Signature: _______________________________________ Date: _____________________ !2 Acknowledgements I am sincerely grateful for the opportunity to conduct my research as part of the School of Literature and Languages at the University of Surrey. I am even more grateful to have worked with my supervisors: Dr. Paul Vlitos, Dr. Alan Johnson, and (for far too short a time) Professor Justin Edwards. Thank you to every teacher who encouraged my love of literature. Thank you, thank you, thank you, to the friends who kept me sane as I took up in a new country away from everything I’ve ever known. -

Crinew Music Re Uoft

CRINew Music Re u oft SEPTEMBER 11, 2000 ISSUE 682 VOL. 63 NO. 12 WWW.CMJ.COM MUST HEAR Universal/NIP3.com Trial Begins With its lawsuit against MP3.com set to go inent on the case. to trial on August 28, Universal Music Group, On August 22, MP3.com settled with Sony the only major label that has not reached aset- Music Entertainment. This left the Seagram- tlement with MP3.com, appears to be dragging owned UMG as the last holdout of the major its feet in trying to reach a settlement, accord- labels to settle with the online company, which ing to MP3.com's lead attorney. currently has on hold its My.MP3.com service "Universal has adifferent agenda. They fig- — the source for all the litigation. ure that since they are the last to settle, they can Like earlier settlements with Warner Music squeeze us," said Michael Rhodes of the firm Group, BMG and EMI, the Sony settlement cov- Cooley Godward LLP, the lead attorney for ers copyright infringements, as well as alicens- MP3.com. Universal officials declined to corn- ing agreement allowing (Continued on page 10) SHELLAC Soundbreak.com, RIAA Agree Jurassic-5, Dilated LOS AMIGOS INVIWITI3LES- On Webcasting Royalty Peoples Go By Soundbreak.com made a fast break, leaving the pack behind and making an agreement with the Recording Word Of Mouth Industry Association of America (RIAA) on aroyalty rate for After hitting the number one a [digital compulsory Webcast license]. No details of the spot on the CMJ Radio 200 and actual rate were released. -

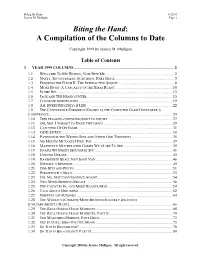

In the Archives Here As .PDF File

Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 1 Biting the Hand: A Compilation of the Columns to Date Copyright 1999 by Jessica M. Mulligan Table of Contents 1 YEAR 1999 COLUMNS ...................................................................................................2 1.1 WELCOME TO MY WORLD; NOW BITE ME....................................................................2 1.2 NASTY, INCONVENIENT QUESTIONS, PART DEUX...........................................................5 1.3 PRESSING THE FLESH II: THE INTERACTIVE SEQUEL.......................................................8 1.4 MORE BUGS: A CASUALTY OF THE XMAS RUSH?.........................................................10 1.5 IN THE BIZ..................................................................................................................13 1.6 JACK AND THE BEANCOUNTER....................................................................................15 1.7 COLOR ME BONEHEADED ............................................................................................19 1.8 AH, SWEET MYSTERY OF LIFE ................................................................................22 1.9 THE CONFERENCE FORMERLY KNOWN AS THE COMPUTER GAME DEVELOPER’S CONFERENCE .........................................................................................................................24 1.10 THIS FRAGGED CORPSE BROUGHT TO YOU BY ...........................................................27 1.11 OH, NO! I FORGOT TO HAVE CHILDREN!....................................................................29 -

'Across the Evening Sky': the Late Voices of Sandy Denny, Judy Collins

© Copyrighted Material Chapter 9 ‘Across the Evening Sky’: The Late Voices of Sandy Denny, Judy Collins and Nina Simone Richard Elliott In 2006, shortly before her 67th birthday, the American singer-songwriter Judy Collins undertook a tour of Australia and New Zealand, her first visit to the region in forty years. A number of press features and interviews accompanied Collins’s visit, several of which were still featured at the top of the ‘Press’ section of the artist’s website at the time of writing this chapter. One of the features, entitled ‘Who Knows Where the Time Goes?’ after one of Collins’s 1960s hits, presented a reflection on the artist’s career alongside observations on age and assertions of continued vitality.1 Another, entitled ‘Gem of a Voice Shines On’, described some of Collins’s most successful performances, including her recording of Joni Mitchell’s ‘Both Sides Now’. ‘Its harpsichord tinkling has dated’, wrote the journalist, ‘but Collins’ voice, warm and wise beyond its years, renders the song timeless.’2 I use these examples because they provide a foretaste of the themes of age, time and experience with which I wish to engage in this chapter, as well as a reference to the song upon which I will base my observations. The first aspect to note is the way in which an artist of Collins’s longevity can afford to leave her website out of date in terms of publicity; the fact that the featured stories are seven years old at the time of access matters little when considering an artist whose performing career spans more than five decades.