Genetic Variation in Native and Translocated Populations of the Laysan Finch (Telespiza Can Tans)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawaiian Monk Seal Pupping Locations in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands'

Pacific Science (1990), vol. 44, no. 4: 366-383 0 1990 by University of Hawaii Press. All rights reserved Hawaiian Monk Seal Pupping Locations in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands' ROBINL. wESTLAKE2'3 AND WILLIAM G. GILMARTIN' ABSTRACT: Most births of the endangered Hawaiian monk seal, Monuchus schuuinslundi, occur in specific beach areas in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Data collected from 1981 to 1988 on the locations of monk seal births and of the first sightings of neonatal pups were summarized to identify preferred birth and nursery habitats. These areas are relatively short lengths of beach at the breeding islands and have some common characteristics, of which the pri- mary feature is very shallow water adjacent to the shoreline. This feature, which limits access by large sharks to the water used by mother-pup pairs during the day, should enhance pup survival. THE HAWAIIANMONK SEAL, Monachus at Kure Atoll, Midway Islands, and Pearl and schauinslundi, is an endangered species that Hermes Reef. Some of the reduced counts occurs primarily in the Northwestern Ha- were reportedly due to human disturbance waiian Islands (NWHI) from Nihoa Island (Kenyon 1972). Depleted also, but less drama- to Kure Atoll (Figure 1). The seals breed at tically during that time, were the populations these locations as well, with births mainly oc- at Lisianski and Laysan islands. Although curring from March through June and peaking one could speculate that a net eastward move- in May. Sightings of monk seals are frequent ment of seals could account for the increase around the main Hawaiian Islands and rare in seals at FFS along with the reductions at at Johnston Atoll, about 1300 km southwest the western end, the available data on resight- of Honolulu (Schreiber and Kridler 1969). -

Status Assessment of Laysan and Black-Footed Albatrosses, North Pacific Ocean, 1923–2005

Status Assessment of Laysan and Black-Footed Albatrosses, North Pacific Ocean, 1923–2005 Scientific Investigations Report 2009-5131 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Photograph of Laysan and black-footed albatrosses. Photograph taken by Eric VanderWerf, Pacific Rim Conservation. Status Assessment of Laysan and Black-Footed Albatrosses, North Pacific Ocean, 1923–2005 By Javier A. Arata, University of Massachusetts-Amherst, Paul R. Sievert, U.S. Geological Survey, and Maura B. Naughton, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Scientific Investigations Report 2009-5131 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Arata, J.A., Sievert, P.R., and Naughton, M.B., 2009, Status assessment of Laysan and black-footed albatrosses, North Pacific Ocean, 1923–2005: U.S. -

Potential Effects of Sea Level Rise on the Terrestrial Habitats of Endangered and Endemic Megafauna in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

Vol. 2: 21–30, 2006 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Printed December 2006 Previously ESR 4: 1–10, 2006 Endang Species Res Published online May 24, 2006 Potential effects of sea level rise on the terrestrial habitats of endangered and endemic megafauna in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Jason D. Baker1, 2,*, Charles L. Littnan1, David W. Johnston3 1Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA, 2570 Dole Street, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA 2University of Aberdeen, School of Biological Sciences, Lighthouse Field Station, George Street, Cromarty, Ross-shire IV11 8YJ, UK 3Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research, 1000 Pope Road, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA ABSTRACT: Climate models predict that global average sea level may rise considerably this century, potentially affecting species that rely on coastal habitat. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) have high conservation value due to their concentration of endemic, endangered and threatened spe- cies, and large numbers of nesting seabirds. Most of these islands are low-lying and therefore poten- tially vulnerable to increases in global average sea level. We explored the potential for habitat loss in the NWHI by creating topographic models of several islands and evaluating the potential effects of sea level rise by 2100 under a range of basic passive flooding scenarios. Projected terrestrial habitat loss varied greatly among the islands examined: 3 to 65% under a median scenario (48 cm rise), and 5 to 75% under the maximum scenario (88 cm rise). Spring tides would probably periodically inun- date all land below 89 cm (median scenario) and 129 cm (maximum scenario) in elevation. Sea level is expected to continue increasing after 2100, which would have greater impact on atolls such as French Frigate Shoals and Pearl and Hermes Reef, where virtually all land is less than 2 m above sea level. -

A New Tern (Sterna) Breeding Record for Hawaii!

Pacific Science (1991), vol. 45, no. 4: 348-354 © 1991 by University of Hawaii Press. All rights reserved A New Tern (Sterna) Breeding Record for Hawaii! SHEILA CONANT,2 ROGER CLAPP,3 LISA HIRUKI,4 AND BARRY CHOy 5 ABSTRACT: Recent observations of terns, either the Old World Little Tern (Sterna albifrons) or the New World Least Tern (Sterna antillarum), at Pearl and Hermes Reef in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands have documented that one of these species bred there in 1988 and possibly also in the several preceding years. Two small Sterna terns were first observed at Pearl and Hermes in 1984, and the numbers subsequently observed there gradually increased until fivebirds were recorded in 1988. In 1988 a nest containing three eggs was found , and at least one egg produced a nestling. No small Sterna terns were seen during a 2-week visit to the atoll in 1989 or a 2-day visit in 1990. No specimens were collected, and photographs taken do not permit specific identification of the birds. We favor S. albifrons sinensis because there are now specimen records of Asiatic Little Terns from French Frigate Shoals and Midway Atoll and a sight record from Laysan Island, and because a review of prevailing wind systems in the Pacific and other vagrant bird records from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands suggest that such birds are more likely to arrive from the west than from the east. EXAMINATION OF RECORDS of vagrants from Finch (Telespiza cantans) and the Hawaiian the Hawaiian Islands (Clapp, in litt.) suggests Monk Seal (Monachus schauinslandi), we also that birds from the Northwestern Hawaiian made incidental observations of seabirds and Islands, particularly the more westerly ones, shorebirds. -

Amerson Et Al. (1974) the Natural History Of

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 174 THE NATURAL HISTORY OF PEARL AND HERMES REEF, NORTHWESTERN HAWAIIAN ISLANDS by A. Binion Amerson, Jr., Roger C. Clapp, and William 0. Wirtz, Ii Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION with the assistance of The Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C., U.S.A. ACKNOWLEDGMENT The Atoll Research Bulletin is issued by the Smithsonian Institution as a part of its Tropical Biology Program. It is co- sponsored by the Museum of Natural History, the Office of Environ- mental Sciences, and the Smithsonian Press. The Press supports and handles production and distribution. The editing is done by the Tropical Biology staff, Botany Department, Museum of Natural History. The Bulletin was founded and the first 117 numbers issued by the Pacific Science Board, National Academy of Sciences, with financial support from the Office of Naval Research. Its pages were largely devoted to reports resulting from the Pacific Science Board's Coral Atoll Program. The sole responsibility for all statements made by authors of papers in the Atoll Research Bulletin rests with them, and statements made in the Bulletin do not necessarily represent the views of the Smithsonian nor those of the editors of the Bulletin. Editors F. R. Fosberg M.-H. Sachet Smithsonian Institution Washington, D. C. 20560 D. R. Stoddart Department of Geography University of Cambridge Downing Place Cambridge, England TABLE OF CONTENTS ! . LIST OF FIGmS ......................................................ill... LIST OF -

Peregrine Falcon Predation of Endangered Laysan Teal and Laysan Finches on Remote Hawaiian Atolls

Technical Report HCSU-065 PEREGRINE FALCON PREDATION OF ENDANGERED LAYSAN TEAL AND LAYSAN FINCHES ON REMOTE HAWAIIAN ATOLLS 1 2 1 Michelle H. Reynolds , Sarah A. B. Nash , and Karen N. Courtot 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, Kīlauea Field Station, P.O. Box 44, Hawai`i National Park, HI 96718 2 Hawai`i Cooperative Studies Unit, University of Hawai`i at Hilo, P.O. Box 44, Hawai`i National Park, HI 96718 Hawai`i Cooperative Studies Unit University of Hawai‘i at Hilo 200 W. Kawili St. Hilo, HI 96720 (808) 933-0706 April 2015 This product was prepared under Cooperative Agreement CAXXXXXXXXX for the Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center of the U.S. Geological Survey. This article has been peer reviewed and approved for publication consistent with USGS Fundamental Science Practices (http://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1367/). Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ....................................................................................................................... iii List of Figures ...................................................................................................................... iii Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

Abstract Book for Kūlia I Ka Huliau — Striving for Change by Abstract ID 3

Abstract Book for Kūlia i ka huliau — Striving for change by Abstract ID 3 Discussion from Hawai'i's Largest Public facilities - Surviving during this time of COVID-19. Allen Tom1, Andrew Rossiter2, Tapani Vouri3, Melanie Ide4 1NOAA, Kihei, Hawaii. 2Waikiki Aquarium, Honolulu, Hawaii. 3Maui Ocean Center, Maaleaa, Hawaii. 4Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii Track V. New Technologies in Conservation Research and Management Abstract Directors from the Waikiki Aquarium (Dr. Andrew Rossiter), Maui Ocean Center (Tapani Vouri) and the Bishop Museum (Melanie Ide) will discuss their programs public conservation programs and what the future holds for these institutions both during and after COVID-19. Panelists will discuss: How these institutions survived during COVID-19, what they will be doing in the future to ensure their survival and how they promote and support conservation efforts in Hawai'i. HCC is an excellent opportunity to showcase how Hawaii's largest aquaria and museums play a huge role in building awareness of the public in our biocultural diversity both locally and globally, and how the vicarious experience of biodiversity that is otherwise rarely or never seen by the normal person can be appreciated, documented, and researched, so we know the biology, ecology and conservation needs of our native biocultural diversity. Questions about how did COVID-19 affect these amazing institutions and how has COVID-19 forced an internal examination and different ways of working in terms of all of the in-house work that often falls to the side against fieldwork, and how it strengthened the data systems as well as our virtual expression of biodiversity work when physical viewing became hampered. -

PMNM BMP # 007 1 Updated 8 June 2021 BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES (BMPS) for TERRESTRIAL BIOSECURITY Papahānaumokuākea Marine

PMNM BMP # 007 BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES (BMPS) FOR TERRESTRIAL BIOSECURITY Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument The following conditions and rules aim to conserve and protect biologically unique terrestrial environments in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (Monument or PMNM). These unique uplands, shorelines, and shallow reef habitats provide refuge for many rare and endemic wildlife found nowhere else on Earth. Many of these species are formally listed as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Endemic and listed plants, animals and arthropods are especially vulnerable to competition or habitat degradation from invasive or non-native species. These potential introductions may cause the extinction of endemic wildlife species and the destruction of entire terrestrial ecosystems or coral reef communities. Notable local examples include: the introduction of rabbits to Laysan Island (Kamole) in 1902, which caused the extinction of numerous plant and arthropod species, and three endemic land bird species; the introduction of the annual grass, common sandbur to Laysan Island (Kamole) where it has crowded out native bunch grass (kawelu) thus, eliminating nesting habitat for the endangered ‘Ekupu‘u (Laysan finch, Telespiza cantans) the introduction of rats to many Pacific Islands causing the extirpation of many burrowing seabird colonies as well as native plant communities; and, the introduction and proliferation of numerous ant species throughout the Pacific Islands to the widespread detriment of endemic plant and arthropod species. Several of the islands within the Monument are pristine, and as a result are rich in rare and endemic plants and animals. Nihoa Island has at least 17 endemic and rare insect species, 5 endangered plants and 2 endangered birds. -

Phycological Newsletter

Summer/Fall 2020 Volume 56 Number 2 October 9, 2020 PHYCOLOGICAL NEWSLETTER MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Gree$ngs Phycological Friends, As 2020 con)nues the inexorable march to comple)on, I am reminded of the old aphorism/ curse “may you live in interes)ng )mes”. Changes are always fraught with challenges, but as biologists we recognize that such changes are also opportuni)es for novel innova)ons and strategies. How many of our favorite taxa, biochemical pathways, interes)ng features, etc. have come about aEer major upheavals? One of the great parts about my job is that I have an opportunity to interact with numerous phycologists diligently working even during these trying )mes. The fantas)c members who comprise the PSA are thriving and looking forward to new endeavors. “Give me some examples”, you say. Well... First, this was an unprecedented year for the PSA in terms of the Annual Mee)ng. While Covid-19 prevented us from a tradi)onal, in-person event, the extraordinary virtual program commiTee (Amy Carlile, Patrick Martone, Sabrina Heiser, and Eric Linton) craEed an epic on-line one instead. The amazing thing about this gra)s endeavor: we had 800 folks register with 438 unique views the first day alone! Clearly, we are reaching a wide swath of the planetary phycological community, and I am sure that we will con)nue to employ some of the great features we explored this year in subsequent mee)ngs. Presen)ng member-submiTed lightning talks, the mee)ng also showcased the Student Symposium, with Patricia Glibert, Bilassé Zongo, and Nelson Valdivia. -

Nest Substrate Variation Between Native and Introduced Populations of Laysan Finches

Wilson Bull., 102(4), 1990, pp. 59 l-604 NEST SUBSTRATE VARIATION BETWEEN NATIVE AND INTRODUCED POPULATIONS OF LAYSAN FINCHES MARIE P. MORIN ’ AND SHEILA CONANT~ AasrnAcr.-On Laysan Island, the endangered, endemic Laysan Finch (Telespizacantans) nests almost exclusively in the native bunchgrass Erugrostisvuriubilis. Experimental nest boxes provided were never used for nesting. Marine debris was not used as nest substrate on Laysan Island. In contrast, the introduced Laysan Finch populations on four islands at Pearl and Hermes Reef used a wide variety of native and alien plants as nest substrates, as well as various kinds of human-made debris. However, nest boxes provided at Pearl and Hermes Reef were not used as nest substrates by finches. Erugrostisvuriabilis is uncommon on Pearl and Hermes Reef, except on Seal-Kittery Island, but is common on Laysan where it is the preferred nest substrate. Erugrostisis a dense bunchgrass which probably provides the nest with good protection from sun, rain, wind, disturbance, and predators. On Pearl and Hermes Reef, where Erugrostisvuriubilis is uncommon, other plants that provide dense cover are used as nest substrates, and human-made debris that provides some cover is also utilized. It is unclear why nest boxes were never used as nest substrates at either site. We suggest that the conservation of Iaysan Finches on Laysan Island will require the mainte- nance of a native ecosystem where Eragrostisvuriabilis is a major vegetation component. Otherwise, changes in behavior, morphology, and energy expenditure associated with en- vironmental differences are likely to occur, and may have already occurred in the introduced populations on Pearl and Hermes Reef. -

Hawaiian Monk Seal Pupping Locations in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands!

Pacific Science (1990), vol. 44, no. 4: 366-383 © 1990 by University of Hawaii Press. All rights reserved Hawaiian Monk Seal Pupping Locations in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands! 2 3 2 ROBIN L. WESTLAKE • AND WILLIAM G. GILMARTIN ABSTRACT: Most births of the endangered Hawaiian monk seal, Monachus schauinslandi, occur in specific beach areas in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Data collected from 1981 to 1988 on the locations of monk seal births and ofthe first sightings ofneonatal pups were summarized to identify preferred birth and nursery habitats. These areas are relatively short lengths of beach at the breeding islands and have some common characteristics, of which the pri mary feature is very shallow water adjacent to the shoreline. This feature, which limits access by large sharks to the water used by mother-pup pairs during the day, should enhance pup survival. THE HAWAIIAN MONK SEAL, M onachus at Kure Atoll , Midway Islands, and Pearl and schauinslandi, is an endangered species that Hermes Reef. Some of the reduced counts occurs primarily in the Northwestern Ha were reportedly due to human disturbance waiian Islands (NWHI) from Nihoa Island (Kenyon 1972).Depleted also, but lessdrama to Kure Atoll (Figure 1). The seals breed at tically during that time, were the populations these locations as well, with births mainly oc at Lisianski and Laysan islands. Although curring from March through June and peaking one could speculate that a net eastward move in May. Sightings of monk seals are frequent ment of seals could account for the increase around the main Hawaiian Islands and rare in seals at FFS along with the reductions at at Johnston Atoll, about 1300 km southwest the western end, the available data on resight of Honolulu (Schreiber and Kridler 1969). -

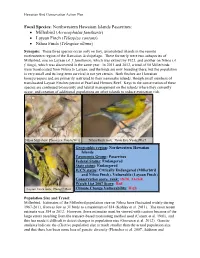

Focal Species: Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Passerines: Millerbird (Acrocephalus Familiaris) Laysan Finch (Telespiza Cantans) Nihoa Finch (Telespiza Ultima)

Hawaiian Bird Conservation Action Plan Focal Species: Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Passerines: Millerbird (Acrocephalus familiaris) Laysan Finch (Telespiza cantans) Nihoa Finch (Telespiza ultima) Synopsis: These three species occur only on tiny, uninhabited islands in the remote northwestern region of the Hawaiian Archipelago. There formerly were two subspecies of Millerbird, one on Laysan (A. f. familiaris), which was extinct by 1923, and another on Nihoa (A. f. kingi), which was discovered in the same year. In 2011 and 2012, a total of 50 Millerbirds were translocated from Nihoa to Laysan, and the birds are now breeding there, but the population is very small and its long-term survival is not yet certain. Both finches are Hawaiian honeycreepers and are primarily restricted to their namesake islands, though small numbers of translocated Laysan Finches persist at Pearl and Hermes Reef. Keys to the conservation of these species are continued biosecurity and habitat management on the islands where they currently occur, and creation of additional populations on other islands to reduce extinction risk. Nihoa Millerbird. Photo Eric VanderWerf Nihoa Finch male. Photo Eric VanderWerf Geographic region: Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Taxonomic Group: Passerines Federal Status: Endangered State status: Endangered IUCN status: Critically Endangered (Millerbird and Nihoa Finch), Vulnerable (Laysan Finch) Conservation score, rank: 18/20, At-risk Watch List 2007 Score: Red Laysan Finch male. Photo C. Rutt Climate Change Vulnerability: High Population Size and Trend: Millerbird. Estimates of the Millerbird population size on Nihoa have fluctuated widely during 1967-2011, from as few as 31 birds to a maximum of 814 (Kohley et al. 2011).